On those nights when I have stayed up too late, binge-watching shows on Netflix or scrolling through Twitter, I have the disturbing sensation that the rest of my body has ceased to exist, and I am nothing but a giant eyeball, absorbing signals from my screen. The illusion persists, even as earbuds start to weigh uncomfortably on my ears and the bed I sit on hardens against my back. The brightness of the screen absorbs my focus like a porch light does a moth’s. In these moments, my body is telling me more articulately than the guilty tape loop in my head that I have stayed in one place too long, that I’ve seen too much.

Something similar happens in the way digital technology is often discussed. Its more obvious engagement with sight distracts us from what is going on both beneath the screen and beyond our retinas. The visual component — the stakes for what we see and how we are seen — is overemphasized; its use as a metaphor becomes literalized.

Consider, for example, the choice of the phrase “computer vision” to describe a computer’s ability to glean information from images. Vision has connotations beyond mere sight to suggest a prophetic ability to (for)see what others miss. It implies revealed, rather than acquired, knowledge. Assigning this property to computers suggests they are making autonomous visual judgments that are similar in process to ours but from a different, computerized perspective.

In fact, the phrase describes the opposite, as this helpful breakdown from the tech company Yandex explains. Humans train computers to recognize specific content by “showing” them a glut of images that both do and do not include the item the programmer wants the computer to recognize. But in order for the computer to perceive anything, the programmer must translate the images into numbers using algorithms. Often, this means selecting the brightest or most contrasting parts of an image and converting them into numerical descriptors that the computer can then group with similar descriptors from other images in a numerized cluster. The process from the machine’s point of view is not something we would readily describe or experience as seeing. It’s a textural process of breaking down and recombining — more like a dissection than a gaze. But it is the human point of view that determines what the computer is trained to analyze in this nonhuman way.

“Computer vision,” then, mislabels the agency and the process, a verbal misdirection that obscures serious problems. A study by Georgetown University researcher Claire Garvey found that African Americans were more likely to be subjected to facial recognition software in criminal cases and the software is more likely to be wrong. It’s often wrong, according to MIT Media Lab researcher Joy Buolamwini, because it has been trained to recognize faces by mostly white engineers, who write algorithms based on the facial features they think are important and train the computers on data sets composed of mostly white faces. Labeling facial recognition a type of “computer vision” dangerously implies a level of nonhuman neutrality and insight that the software does not posses. In fact, it is a mechanized augmentation of human visual biases and mistakes.

“Computer vision” is verbal misdirection, mislabeling the agency and the process

It is true that the cutting edge of computer vision development trains using deep learning — feeding computers unlabeled images until they learn to recognize patterns on their own. While human visual standards still judge the success of this training, the process is more intrinsic to the machine than shallower computer vision techniques. But even when computer vision doesn’t reproduce human visual biases, the way it has been developed and named reflects our overall pro-sight bias. Over and over, we emphasize visual perception at the expense of other senses. Sight-based metaphors abound outside the discourse of technology. Even in this essay, I’ve caught myself using a few of them: obscures, reflection, point of view. We are obsessed with sight, so it makes sense that we’d want to train our machines to process visual information. Stanford AI scientist Fei-Fei Li encapsulated that vision fixation when she said, “If we want machines to think, we need to teach them to see.”

One of the reasons Li valorizes computer vision is in the hopes that it will be able to see what humans are not capable of seeing in their totality: the videos and pictures that make up 85 percent of internet content, what she calls “the dark matter of the digital age.” No human could physically “see,” much less understand, all those images, but a well-trained machine potentially could. The alternative — that the images we’d posted might remain unseen — is not considered. Instead, we must craft an audience. This suggests that the push to develop computer vision is more about our desire to be perceived in a way that we understand than it is about considering how thinking machines would most easily perceive the world.

The flip side of that desire to always be seen is a nervousness about always being seeable. Anxieties surrounding digital surveillance are disproportionately expressed through visual metaphors. When Edward Snowden revealed the extent of the NSA’s spying program, sales of George Orwell’s 1984 went up by 6,000%. Similarly, the panopticon, an 18th century design for a prison organized around sight lines, had its turn in the spotlight. “Snowden showed us how big the panopticon really was,” read one Guardian headline.

As with our general vision bias, the overemphasis on visual surveillance predates Snowden and CCTV. According to the BBC’s Vocabularist, the word surveillance entered English in the late 18th century from a French word derived from the Latin super and vigilantia, or “over” and “watchfulness.” When it first came into the English lexicon, in the wake of the French Revolution, it was associated by many with the Comité de Surveillance and the excesses of the Reign of Terror. It has been associated with visual observation and the abuse of power it enables ever since.

Despite its etymology, though, the practice of surveillance has never been purely visual. As the Auditory Culture Reader points out, “accounts of surveillance often begin with Foucault’s account of Bentham’s panopticon,” which emphasizes how the prison was designed to allow the warden to see all the inmates. But Bentham also designed a series of listening tubes so that the warden could hear what the prisoners said. Tapped phones and bugged apartments figure into many popular representations of surveillance, from The Conversation to The Lives of Others and beyond.

Focusing on the visual fails to account for the full extent of surveillance’s potential for violation

Still, when we want to explain the experience of digital surveillance, we tend to defer to the eye, which posits a conceptual distance between watcher and watched. Seeing — unlike smelling, tasting, touching — implies spatial separation, and with that comes a sense of control: It offers the comforting illusion that one merely needs to hide from view to escape. But focusing on the visual fails to account for the full extent of surveillance’s potential for violation, or the surprising intimacy of its role in our lives.

The idea of online “stalking,” for example, imposes a visual sense of space on a behavior that is more amorphous in practice. Facebook “stalking” can actually be a prelude to intimacy in a way that spying through a window cannot: Scanning a crush’s social media accounts to make sure they are single and don’t have any deal-breaking political opinions is just a step before messaging them to ask for a date. And the line between stalking and connecting is mediated by means of touch. The currently defunct Facebook “poke” was one non-visual metaphor that referenced how we use touch to instigate communication. If the phrasing sounds uncomfortably intimate, it should. Focusing on the tactile process of online communication gets at the truth that it is still human connection — as potentially intimate and fraught as face-to-face interaction.

Similarly, examining digital surveillance through the sense of touch uncovers the violence it facilitates against people’s bodies. Looked at through the lens of sight, the battle between surveiller and surveilled seems a technical arms race that is leaving the body behind in a surface-level game of outlandish fashions, shuffling masks, and hide and seek. Individuals physically put something over their face or body to cover themselves from the machine gaze — as with artist Adam Harvey’s CV Dazzle and Hyperface — and programmers then develop algorithms to digitally remove them. Researchers at the University of Cambridge trained algorithms to match the identity of people wearing scarves 77 percent of the time, and hats, scarves, and glasses together 55 percent of the time. Meanwhile, researchers at Carnegie Mellon have discovered that by printing specific patterns on glasses frames, they can fool algorithms into mistaking the wearer for someone else.

But wearing disguises to baffle what mechanical sensors can process is also a tactile matter; detection is as much about undressing as it is about recognizing. Probing this arms race through the sense of touch reveals it’s a matter of prying fingers as well as scanning eyes. The New Scientist article on the Cambridge study described computers “seeing through” disguises, but the tactic also brings to mind a blind person running their hands over a loved one’s face.

The idea that computers are trained to do from afar what we must do up close gets at the process of computer surveillance better than futuristic associations with X-ray vision. If we instead emphasized the tangible over the visual, it could draw out the full extent of the violation inherent in the development and nonconsensual use of such technologies in a public space. It is one thing to be seen when you don’t want to be; it is another thing to be forcibly stripped.

Surveillance can not only see us, but it can touch us. Likewise, we willingly give our devices sensitive information about ourselves by way of touch, whether through unlocking protocols like Touch ID or through more quotidian gestures we perform on our devices. But the emphasis on invasive surveillance as visual allows the more tactile modes of data collection to seem comparatively benign.

The commercials for the first iPhone, which demonstrated its touch-screen capabilities, showed the new phone against a black screen, held and manipulated by a disembodied hand. The screen and its contents were the main event; the fingers doing the swiping an expedient instrument. “This is your music,” the narrator intoned, “this is your email,” as the finger pressed the icons for these functions and scrolled through the files, an efficient and intuitive means to an end: what you see onscreen.

Machine detection is a matter of prying fingers as well as scanning eyes

Since then, digital technology has trained us to expect immediate results from touching screens. The repetitive nature of the motions involved, as well as the flatness and smoothness of keyboard and screen, means the touching often slips past conscious awareness. In a video on YouTube, “A Magazine Is an iPad That Does Not Work,” a one-year-old tries to enlarge the pages of magazines with a finger-spread gesture. Around the 50-second mark, frustrated with the magazine’s non-responsiveness, she tests her finger against the skin of her leg, making sure it still dimples. Her engagement with digital technology has so conditioned her sense of touch that when a part of the outside world refuses to behave like a screen, she thinks her finger might be broken.

This suggests that the screen has become so captivating that we’ve come to perceive our bodies as tools in its service rather than the other way around. It’s easy to type and touch on autopilot and only focus on the information the screen shows us. By zoning out on our role in the exchange, we forget that the machine is doing work for us, and that work is increasingly intimate in nature. More and more, digital devices enter our lives as care providers, giving us medical advice, reminding us of important meetings, organizing rideshares, keeping track of our fitness goals, and helping us order food when we’re hungry.

But touch is not merely instrumental; it is also a crucial component of care. Tiffany Fields, head of the Touch Research Institute at the University of Miami’s Miller School of Medicine, conducted studies of elderly individuals. One group received touch-free conversational visits while another group got conversation with a massage. The touch made a difference: the second group reaped more emotional and mental benefits from the interactions than those who just engaged in conversation. It could be that we do not perceive our phones and laptops as caring for us because, while they respond to our touch, they cannot touch us back.

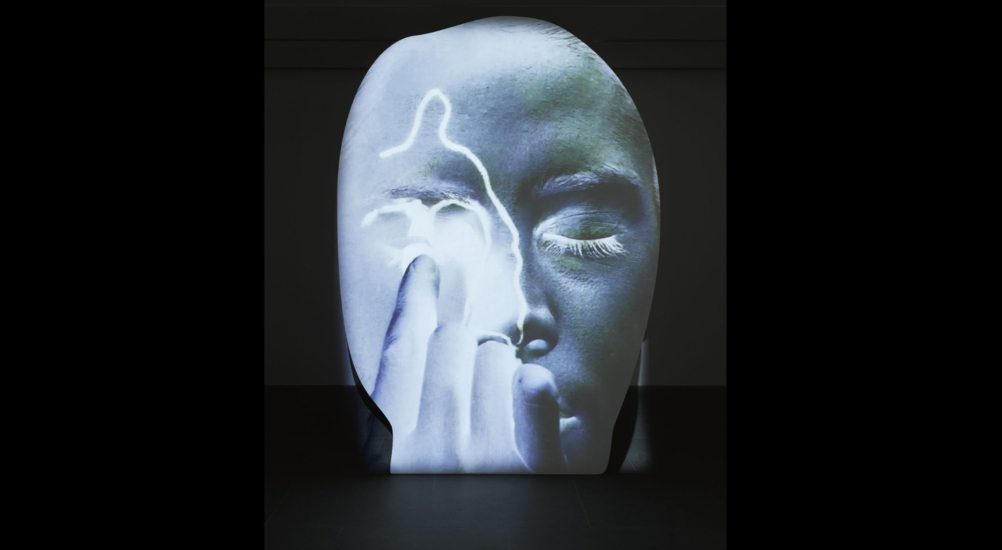

Since we engage with machines through senses beyond sight, it is important to bring that understanding into the way we talk about the uses and abuses of technology. If we mainly focus on computer vision, we may be numbed into viewing our tactile relationship with machines as simple and self-evident rather than fraught and entangled. Most of what our devices see is what we type into them, what we click. At stake in digital privacy rights is not our ability to hide from view, but a broader sense of how we use technology to facilitate care, how we let it touch us. Big Brother isn’t watching from a panopticon. He is cupping our face in his hands.