Earlier this spring, I got into a ferocious argument when a joke about “personal brands” turned into a two-hour debate about whether we are all Kardashians now. The obsession with public identity performance in the digital sphere has supposedly made for a generation of solipsists and inauthentic re-enactors, each with a pithy 140-character Twitter bio.

It’s an argument I’ve encountered frequently, particularly among those nostalgic for an imagined golden age of authentic identity divorced from the need from performance. In “Creating the Self in the Digital Age: Young People and Mobile Social Media,” Toshie Takahashi of Waseda University seems to support that premise. She cites Japanese teenagers who use Facebook to project an image of reajuu, or living life to the fullest, mainly by uploading photos and tagging each other, suggesting that Facebook is, if not responsible for the phenomenon, nonetheless a prime avenue for its intensification.

In support, Takahashi quotes a verbose British teenager who manages to quickly touch on seemingly every narcissist stereotype: “I do want to stand out, in a way … not by what I post but by who I post it to and how often. It’s not necessarily by what I post that I want to stand out, making sure that people don’t forget about me, like, oh don’t forget me [laughs]. Also as a kind of PR, like a personal PR machine, like this is the image I want to give people, how can I remind people that I exist.” The self, it would be easy to say, is rendered nothing more than a commodity by this “machine,” selling itself for social and financial capital in a digital marketplace in which attention doubles as currency. In such a paradigm, this contemporary digital form of self-creation necessitates a necessarily capitalistic conception of the self, complete with a healthy (or perhaps unhealthy) level of market competition.

But as an otherwise confirmed nostalgist myself — and a historian of 19th century French culture — I’m all too conscious that the phenomenon of self-creation is nothing new and hardly contingent on digital media. If anything, the current concern with unseemly self-creation is a replay of the anxieties sparked by 19th century technologies when they were new and were transforming the experience of urban life and public space. A good century and a half before Kim Kardashian Snapchatted her Paris hotel room, confirmed countercultural dandies like Barbey D’Aurevilly and Joséphin Peladan were using the newly broadened boulevards of Paris — and their equally new outward-facing café terraces and gas lamps that made being visible in public both possible and safe — as a canvas for performing identity. The expansion of usable, strollable public space in the increasingly bourgeois cityscape allowed, in turn, for an expansion of the concept of self to fill it. Hence the emergence of the people-watching flâneur.

As department stores began to appear, humans and things were starting to be seen as interchangeable. In this context, deliberate self-creation was deeply radical

It’s possible to make the case that today’s “digital marketplace” is simply an extension of what occurred on the Parisian arcades and boulevards of the 19th century: a transformation of public space from something primarily functional to something commercial to something that is ultimately theatrical. In this transformed public space, people of all social classes could participate in the rites of seeing and being once limited to the upper echelons of society, behind gates or walls. The urban chaos of a terrasse on Boulevard Haussmann, for example, might well be considered a direct material precursor of the Facebook wall.

To speak of a life lived publicly, in both digital and nondigital forms, can be to imply a duality of the self: the “real person” (whose being, thoughts, and circumstances determine who she is) and the “artificial” double who appears before others: a doppelgänger that is, generously, an aspirational figure and, ungenerously, a total sham. This duality rests upon an assumption that one’s true self is static, determined ultimately by the conditions into which one was born — that social mobility is not possible. From this perspective, we are defined not by how we see or would like to see ourselves but by an intrinsic essence that can be expressed, maybe betrayed, but not changed. It’s an intensely class-conscious mentality that I’m particularly aware of in my adoptive country of England, where someone who transgresses shibboleths of dress or manner is casually dismissed as “inauthentic.” Any presentation of ourselves beyond caste parameters is held to necessarily be a lie.

Figures like D’Aurevilly, Peladan, and Charles Baudelaire vehemently rejected this understanding of the performance of self. Instead, they regarded the power to shape one’s identity as an act of creative resistance to a culture increasingly suffused with mass production and consumerism. Department stores began to appear, offering standardized goods that seemed to threaten a standardization of those consuming them. It was an era in which humans and things were starting to be seen as interchangeable — as in one anecdote told by the Goncourt brothers in which prostitutes whisper to their johns about “robot courtesans” hardly distinguishable from female flesh.

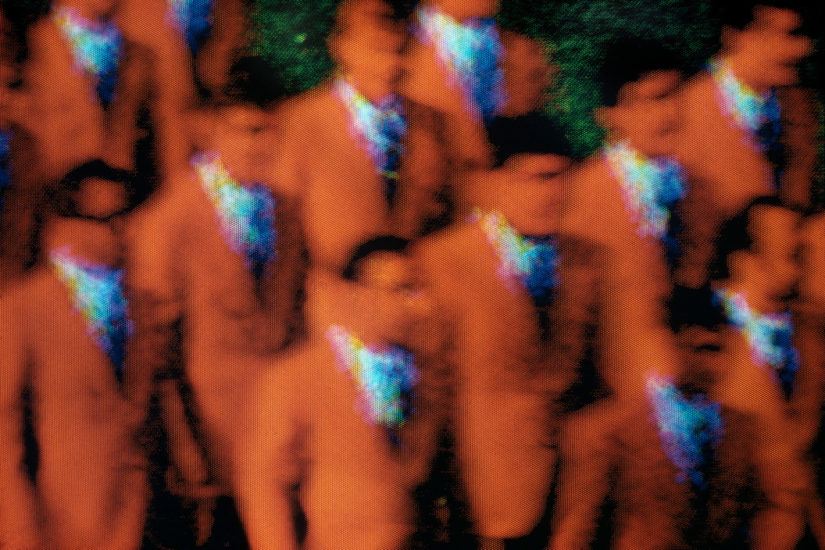

In this context, deliberate self-creation was deeply radical, a way to divide a creator-self from the world of goods that surrounded it, and from la foule, a politicized and loaded term of the era for “the crowd”: the indistinguishable masses defined by their biology (phrenology and other forms of pseudoscience were in full flower), their (lower) social class, and the manipulations of wider market and political forces. From the dandies’ perspective, the people of the crowd may as well have been robots. But self-creation could serve to affirm our irreducibility in a world of reproductions. Even as the lower bourgeoisie began to purchase mass-produced goods at the newly popular department stores, aping the mannerisms of the upper classes, the dandies began to define themselves against any engagement with the reproducible, developing an obsession with singularity that bordered on the monomaniacal. One tale by dramatist Jean Richepin, “Deshoulières,” features a dandy committing murder out of boredom, only to lean back his head at his execution so the guillotine will sever him in a different spot from all other men.

Joséphin Peladan, who was prone to wandering through the streets of Paris in magician’s robes, exhorted his readers to “create your own magic”: Perform the acts of faith and the faith will come

Though they were dandies, they regarded creative self-performance as about more than, say, showing off a nice cravat (or, in the case of Gerard de Nerval, a live lobster on a leash). Rather it was an ethical calling. In his essay “The Painter of Modern Life” Baudelaire wrote of “the burning need to create for oneself a personal originality, bounded only by the limits of the proprieties … a kind of cult of the self.” For Peladan, an occultist writer, self-creation was what he called kaloprosopia, the art of the beautiful person. “One asks what the object of life is,” he wrote. “For a man who thinks, it can only be the occasion and the means to remake the soul that God has given him: to sculpt it into work of art.”

Peladan, who was prone to wandering through the streets of Paris in magician’s robes, exhorted his readers to “create your own magic.” He quoted Saint Ignatius of Loyola: Perform the acts of faith and the faith will come. Performative self-making — externalization — was the first step of a total transformation of the self from animal to spiritual being.

In his advice to actors, director Konstantin Stanislavski exhorts performers to focus on what their character wants the most. Their objectives, their wants, their desires, make the characters who they are: These are not just a part but indeed the very lynchpin of their identity. Why, therefore, should our own aspirational versions of ourselves not be considered equally authentic iterations (if not more so) of our own selves? Why are we not, in other words, who we want to be?

The dandies’ conception of the self was at times astonishingly divorced from the biological, from questions of facticity. A recurring theme in dandy literature is characters who try to transcend basic human acts like eating or sleeping; in Huysmans’s Á Rebours, Des Esseintes tries and fails to feed himself by means of peptone enema. Willed createdness, and the rejection of the biological or the necessary, becomes the measure of successful humanity: We are defined by our actions, not our situatedness.

For Ricoeur, ethics lies in internal consistency — in “keeping one’s word” in future encounters. So our performances publicly may help us shape who we are privately as well

The dandies, of course, take this to extremes. But as 20th century philosopher Paul Ricoeur points out, self, self-conception, and action are not so easily divorced from one another. The stories we tell ourselves about ourselves — including through public performance in the social sphere — also come to govern our actions. “As the literary analysis of autobiography confirms, the story of a life continues to be refigured by all the truthful or fictive stories a subject tells about himself or herself,” he writes in Oneself as Another (1992). “This refiguration makes this life a cloth woven of stories told.” For Ricoeur, that story we tell ourselves about ourselves allows us to be the same “person,” in the sense of selfsame identity, even as our circumstances change.

Those stories are inextricable from public discourse, not only from the audiences to whom they are told but from the whole field of signs, images, and myths that we allow to shape us and determine our actions. As Ricoeur puts it, “the identity of a person or a community is made up of these identifications with values, norms, ideals, models, and heroes, in which the person or the community recognizes itself.” In other words, we are legible to ourselves — and to each other — only in communion with our collective world of stories, of narratives and cultural touchstones. Our understanding of ourselves as heroes, for example, cannot be separated from the cultural sedimentation of Achilles and Patroclus, or King Arthur and Lancelot, or any other narrative repository of our values.

Playing a public role on social media, presenting ourselves as a “character” (the “fun one,” the workaholic, the gleeful bohemian, the “good friend,” the liberal do-gooder, and so forth), is to commit to being that person in the social sphere: to enter into an informal contract with those that witness us to “be that person.” It’s an argument similar to that of the Canadian-American sociologist Erving Goffman, who understood the self as a constant performer, narrating and navigating its selfhood in direct response to its audience. But Ricoeur’s “audience,” as it were, goes beyond the horizontal — the social present — and into the realm of the literary and the mythic. We are creating ourselves not merely “before” others but also “before” the cultural and historical characters we want to be and “before” an imagined future audience: part of a (perhaps unconscious) chain of discourse that links us, in terms of our significance, to an Achilles or an Arthur.

While Goffman allows for a “backstage” — a place where we can be ourselves without theatrical presentation — Ricoeur’s model allows for no such place. There is nowhere beyond language and narrative, and so there is nowhere we are not in dialogue with the stories that have shaped and will continue to shape our self-understanding. For Ricoeur, ethics lies in internal consistency — in “keeping one’s word” in future encounters. So our performances publicly may help us shape who we are privately as well.

Our narrative identities and their refiguring power to shape both our own personal stories and the stories of others are integral to our ability to better ourselves: which is to say, to create versions of ourselves more in line with the values we hold, and the people we most want to be. If sin, for Saint Augustine as for a long line of theologians and philosophers alike, lies in the chasm between who we are and who we want to be, self-improvement can be a matter of closing of that gap in the successful enactment of the narratives that shape us.

In the aftermath of the U.S. election, it is more difficult than ever to deny that we operate at least on some level as characters caught up in enacting versions of ourselves in myths

The dandies, of course, were only concerned in their own narratives — everyone else was rendered an object in the stories they told about themselves, stripped of their own subjectivity or agency. They were artists for which the rest of the world was material for their own self-propagation. But a modified form of dandyism — originality as resistance to capitalistic conceptions of the self, self-creation as a profession of faith in the power of the stories that shape us — nevertheless opens up avenues for active participation in our own selfhood.

Just one example of many: a 2015 University of Pennsylvania study found that participants in an exercise program who used a controlled social media environment to share their progress exercised more than those who did not. By “performing” the identity of pro-exercise, healthy, self-improving individuals in a social setting that rewarded and responded to this, these participants ultimately became those people. To question whether they “really” were or not seems purely sophistic.

But we can take this further: If I make the public choice on social media to present myself as a serious, scholarly type of person, challenging those in my orbit to treat me as such, I make an implicit commitment to those around me: I am this kind of person, I will behave in such and such a way. That narrative of myself, existing in the public sphere, will both affect how people approach me (“What are you doing out at the pub when you’re so busy working on your doctoral thesis?”) and how I view myself (“What am I doing with a pint when I should be finishing my doctoral thesis?”).

If my best self, the self I most long to be — the self that Stanislavski would say is my true self, governed by my wants — is that serious, scholarly academic, why not do as Peladan and Saint Ignatius both suggest: perform the actions of faith first, to let the faith come next? Kim Kardashian may be the bête noire for cultural pessimists, but in the way she puts her life on display for the world to consume, she may the truest believer of all in this creed: a dandy for the democratic era.

Even if self-making opens one to accusations of narcissism, the alternative, if Ricoeur is right, is worse. He points to Austrian writer Robert Musil’s “man without qualities,” who is unwilling or unable to commit himself to any narrative of himself, who lives in a house he cannot even bear to furnish lest his decorating be taken by others as a binding referendum on who he is. If Barbey D’Aurevilly is the proto-Kardashian, then the man without qualities is the anti-Kardashian: someone with no narrative at all. His curious apathy makes him a void: incapable of real engagement because he cannot commit, publicly or privately, to a position, an idea, a way of being. In Ricoeur’s words, he “becomes ultimately nonidentifiable … ridiculous to the point of being superfluous.” Fittingly, the novel in which he appears was never finished.

To be protean, to be “no one” in the sense of a character, is also to be alone. When we strip away or mute all our public qualities, we become not some kind of Rousseauian “natural man” or “woman,” undefiled by Facebook likes or retweets. Rather, we deny ourselves — and one another — the commitment to self-making that performativity allows, the commitment to being to one another the people we intend to be for ourselves. “Give a man a mask,” Oscar Wilde famously said, “and he’ll tell you the truth from another point of view.” So too do our self-performances — airbrushed, filtered, contoured, and all — reveal the truth about ourselves, offered up in the masks we choose.

There is a political dimension, too, to conscious self-making. In the aftermath of the U.S. election, it is more difficult than ever to deny that we operate at least on some level as characters caught up in enacting versions of ourselves in myths. These myths can either be either of our own making or belong to those who seek to use us as supporting characters — just as the dandies of fin de siècle France did — in their own narratives. Donald Trump’s campaign structured a powerful story for his supporters, in which their vote would “drain the swamp” and bring down Wagnerian destruction on the establishment. By this logic, voting became an act of heroic and defiant self-making and meaning making. It’s a reminder of how easily our attempts self-making can be manipulated by another, more powerful, storyteller.

Yet only through conscious control of the stories we tell about ourselves — a discernment rooted in rebellion against the stories foisted upon us by others — that we can resist being rendered la foule. We perform the acts of faith so that the faith may come. So too do we perform them consciously, so that we may not unwittingly perform another’s.