Over 80 percent of Americans today live in cities. The rest of the world is following suit. Currently, just over half of the world’s population live in urban areas, but by 2030, an additional estimated 1.4 billion will move into cities. To say that this poses challenges is an understatement. “It is, I promise, worse than you think,” David Wallace-Wells claimed in his account of the future predicted by climate science. But even beyond the conflicts, food insecurity, economic collapse, disease epidemics, and geological disasters that global warming will wreak, we’re facing other existential crises. It’s unclear whether the jobs people have moved to cities to do will be done by humans for much longer. Computers have been replacing “white collar” jobs for decades and, as the New York Times recently reported, they are starting to program themselves, designing algorithms more complex than anything humans are capable of tracing and understanding. That is, they are becoming like cities themselves, whose complexity has defied efforts at urban planning.

What will cities look like once nearly all humans live in them, but most jobs will have little need for human input? Existing cities are already too broke and too burdened by failing infrastructure to engage with this question. Charles Marohn, writing at Strong Towns, argues that cities are caught up in a “growth Ponzi scheme” — a debt-fueled economic model by which they ensure short-term growth through expensive infrastructure investments that they can’t afford to maintain long-term. But tech companies are in a different situation. Many have thrived by parasitically capitalizing on the social relations that cities make possible, collecting marketable data on residents by mediating their communication and travel, and inserting themselves as brokers for a variety of goods and services that city dwellers provide for each other. Given how valuable cities have already been for tech companies, it should come as no surprise that they would seek to design whole cities directly. As Y Combinator partner Adora Cheung put it earlier this summer, “We think it’s possible to do amazing things given a blank slate … We’re interested in building new cities and we think we know how to finance it.”

Many tech companies consider the city a problem to solve rather than a public institution to participate in

Cheung may as well be speaking on behalf of Facebook, which on July 6 released a video outlining plans for a mixed-use village it is building in Menlo Park, California, where the company has its headquarters. The development plan calls for 1,500 residential units, as well as grocery and other retail stores, a pharmacy, a hotel, and office space. The village isn’t just for its employees; more than 200 units are slated for rental to the public at “below market rates.” On the surface, it seems like the plan is mainly about tightening the company’s grip on the town: “Connections is what we do here at Facebook,” Ashley Quintana, a “community outreach coordinator” at the company, says in the video. “We see ourselves here in the long term, and we want to make sure that we’re being a good neighbor. After all, it takes a village.”

Facebook’s aerial-view diagram of Menlo Park, California.

But even in the short video, Facebook doesn’t shy away from imagining transformations in the larger infrastructure of the San Francisco Bay Area. The Dumbarton Rail Corridor — a 30-year-old public-transit initiative to connect Menlo Park and other present-day tech hubs to existing routes — is referenced multiple times. Elsewhere too, as in this project to deliver internet access from space, Mark Zuckerberg is not exactly hiding his company’s long-term goal to control as many sorts of human “connections” as possible. In his “Building Global Community” manifesto, Zuckerberg presents Facebook’s plan to build global social infrastructure for mutual aid, governance, civic engagement, education, policing, crisis response, news distribution and, most important, intelligent personalization algorithms to make global co-existence tolerable for each individual despite any irreconcilable differences between them.

Cheung claims that Y Combinator is “not interested in building ‘crazy libertarian utopias for techies,’” but instead wants “to build cities for all humans.” But this is hard to imagine. Far easier to picture are those dystopian projections of a world entirely subsumed under and governed by private tech companies: a society in which the ultra-rich enjoy a gated utopia while the vast majority are subjected to inescapable surveillance and intensive social control through vast, interconnected monitoring systems. Like the most dismal and extreme of the possibilities Peter Frase posits in his book Four Futures, this would follow if the combination of climate-driven scarcity, automation, and class-based hierarchy become so rampant and entrenched that “the ruling class no longer depends on the exploitation of working class labor,” and “the poor are merely a danger and an inconvenience.” Rather than a “city for all humans,” this future points to a deeper bifurcation between elites and masses.

For its first village, Facebook has partnered with the European architecture firm OMA. In a 2015 lecture on Future Cities, OMA partner and architect Reinier de Graaf lamented that, since the death of the naive reign of top-down urban planning, city planning no longer belongs to “us” — meaning architects. Instead, traditional city planning in his view has been supplanted by the emergence of “smart” cities, planned and sponsored by tech companies like IBM, Siemens, and Cisco. In a telling example, IBM helped build a massive surveillance control room in Rio de Janeiro from which the city can be monitored in real time.

De Graaf analyzes no less than nine tech company proposals for smart cities and is stunned by a sense of déjà vu; they ooze with the same kind of bold optimism you see in modernist architectural manifestos. Not only do these tech companies consider the city a problem for them to solve rather than a public institution to participate in; but they also, like certain Bible verses, predict apocalypse only to offer redemption. They pledge their intelligent, automated, big data-driven supervision of the “smart city” will solve everything from climate change to resource depletion.

Throughout the whole tradition of architecture, starting from Vitruvius’s Ten Books on Architecture, each new iteration of organizing the world according to certain scientific principles changes what it means to be human. As we watch Houston be subsumed by the ocean and prepare for record-breaking storms as the new normal, it’s worth considering what the long-term effects of such grand “smart city” solutions might be. Modernist architecture may see itself standing on one side of a large fissure, with tech companies on the other side.

Could a tech company actually build cities for “all humans” that would not end up an oppressive authoritarian dystopia? If the history of urban planning is any indication, the answer is no. Any attempt that tech companies make at city planning would likely involve trying to map its complexities with some elaborate formulas. But as architect and theorist Christopher Alexander argues, when humans try to reproduce the level of complexity that emerges when a neighborhood evolves organically over time, the “richness of the living city” is replaced with a “conceptual simplicity” — a process of “compartmentalization” and “dissociation of internal elements” that over time leads to a complete breakdown of its inhabitants.

In the 1965 paper “A City Is Not a Tree,” Alexander classified cities that have emerged more or less spontaneously over a long period of time as “natural cities” and cities that have been deliberately created by designers and planners — the sorts of cities tech companies would likely want to build at scale — as “artificial cities.” Attempts to reproduce natural cities always fail, he argues, “because they merely imitate the appearance of the old, its concrete substance,” he writes. “They fail to unearth its inner structure.”

What is this “inner structure” that new city developments lack? According to Alexander, the “natural city has the organization of a semi-lattice; but when we organize a city artificially, we organize it as a tree.”

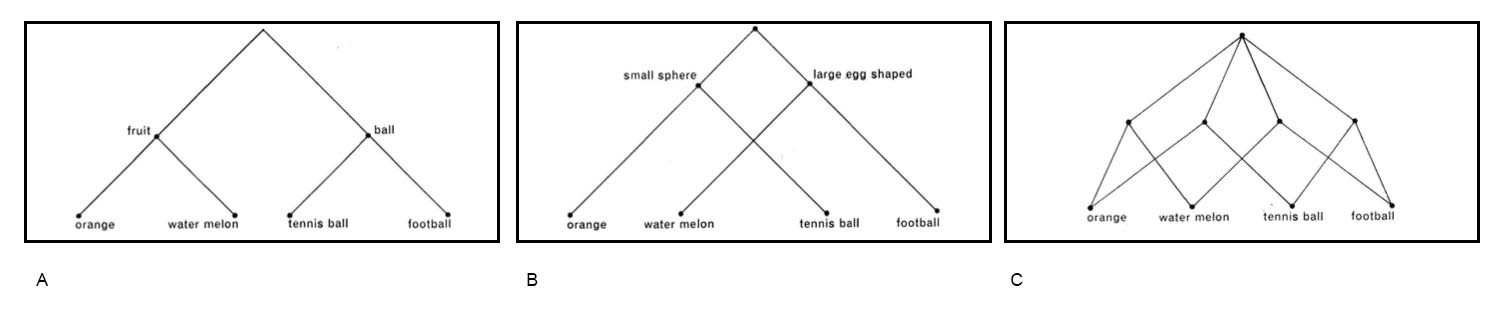

These concepts, “tree” and “semi-lattice,” are set-theory terms that describe two different ways “a large collection of many small systems goes to make up a large and complex system.” In Architecture as Metaphor, philosopher Kojin Karatani explains the difference between the two:

Suppose that we must sort into two groups an orange, a watermelon, a football, and a tennis ball. One way is to sort the two fruits together, the orange and the watermelon, and the two balls together, the football and the tennis ball [figure A]. Another is to sort them according to shape: the two small spheres, the orange and the tennis ball, and the two larger oblong objects, the watermelon and the football [figure B]. Taken individually, either sorting forms a tree structure. But when the two sortings are combined, they result in a semi-lattice [figure C].

When the elements of a set is structured like a tree, its elements are mapped in a linear manner branching out from a single parent, with each element connected to just one parent. This means that relationship of elements in a tree structure is hierarchical — an element is either a “child” or a “parent” of another element, and otherwise wholly separate from other elements. A semi-lattice, unlike the tree structure, allows overlapping sets and includes the point of overlap as another element within the set. Because of this, semi-lattices tend to develop into even more complex structures, since “a semi-lattice based on 20 elements can contain more than a million different subsets” while a tree structure with the same number of elements “can only contain 19 subsets.” Alexander claims that “no matter how complex or chaotic a structure appears, the only model of that structure we are capable of producing is the tree.” Even our attempt at representing the natural city with a semi-lattice yields results that are much simpler than the actual city.

The problem with potential “smart cities” isn’t human inability to produce “natural cities,” but rather what happens to humans in the process

It seems feasible to visualize the relation of 20 subsets; a million is much harder to conceptualize. In my neighborhood in Brooklyn, for example, is the corner of Myrtle Avenue and Broadway, a star-shaped intersection that includes the JMZ subway stop, a 24/7 corner store, a pharmacy, a hardware store, a pizza shop, a liquor store, traffic lights, trash cans, water pipes, electric wires, a number of bodegas, beauty salons and restaurants, among other things. Every day, this busy block is traversed by people on their way to work and school, to meet up with someone, to ask for spare change, or buy something to eat; cars, trains, traffic signals, weather changes, street vendors and store employees, sanitation workers, rats and bacteria all partake in the movement and interactions of the corner and its elements. If the light turns red when a person getting off the train is about to cross the street, they might walk into the coffee shop to pick up a snack and hand their spare change to the person holding the door on their way out.

How would you visualize this intersection? If you imagined this corner as mapped from an aerial view, you would draw the outline of each object, putting it either inside something else or next to another object — essentially forming a tree structure. In the middle of the Facebook village infomercial, we can see a group of young white men drawing up exactly this kind of representation.

To represent the corner as a semi-lattice would be trickier. You would first have to identify which elements form subsets by identifying the way people interact with them. Then you would have to identify which of these subsets overlap with which others through complex interactions. You could do this by drawing a similar map as the one forming a tree structure, then circling subsets and collections of subsets. It’s likely your paper would soon be completely covered in lines, and you still would only have captured a fraction of it.

If someone tried to re-create this corner from scratch someplace else, the result would be even more reductive. Instead of abstracting from existing, individual elements, they would have to project generic needs and behaviors onto potential inhabitants. Even if the architect were one of those potential residents, their plan couldn’t possibly reflect how the people in my actual neighborhood live, interact, support each other, maintain distance and closeness.

The urban renewal initiatives that ravaged especially black and low-income neighborhoods in the U.S. throughout the 20th century provide a striking example of the disastrous consequences of forcing a tree-like architectural plan onto a community. Urban planners tore down entire neighborhoods to make way for concrete complexes nobody wanted to live in or care for, like San Francisco’s Fillmore District, Brooklyn’s Sunset Park, and the Bronx neighborhood Spuyten Duyvil. As Jane Jacobs explains in The Death and Life of Great American Cities, such programs were informed by initiatives like Ebenezer Howard’s Garden City of 1898 and Le Corbusier’s Radiant City of the 1920s, both of which reduced human life to a specific set of functions and needs, designated specific locations for each activity, and declared city streets and sidewalks unnecessary for city life. Their ideas came to inform what Jacobs calls orthodox urban planning, which she characterizes as follows:

The street is bad as an environment for humans; houses should be turned away from it and faced inward, toward sheltered greens. Frequent streets are wasteful, of advantage only to real estate speculators who measure value by the front foot. The basic unit of city design is not the street, but the block and more particularly the super-block. Commerce should be segregated from residences and greens. A neighborhood’s demand for goods should be calculated “scientifically,” and this much and no more commercial space allocated. The presence of many other people is, at best, a necessary evil, and good city planning must aim for at least an illusion of isolation and suburban privacy.

Orthodox urban planners “wrote off the intricate, many-faceted, cultural life of the metropolis,” the many overlapping systems that according to Jacobs held cities together — children playing in the street, store owners keeping watch, people having to use the sidewalk thereby interacting with strangers. Such neighborhoods often decayed rapidly once the “renewal” was complete. Following in the footsteps of Le Corbusier and Howard, urban planners approached housing projects as if they were terrariums — contained, predictable, and simple. When subjected to Howard and Le Corbusier’s super-blocks — which often turned the sidewalk into a dead no-man’s land by moving people up into residential towers, relegating kids to massive interior courtyards and shopping to windowless malls optimized for chain stores — the delicate network of relationships and social norms broke down. This in turn was used to authorize racial profiling, mass incarceration, and intensified surveillance from police.

By the late 1970s, these much criticized “urban renewal” programs were mostly abandoned, but life in the neighborhoods they transformed continued, however precariously. Their failure was, in a cynical sense, quite productive and paved the way for lots of unintended consequences — gentrification, the carceral state, ironic nostalgia for shopping malls.

Jacobs often said that cities pose the problem of organized complexity — the sort of complexity that the semi-lattice’s exponential proliferation of groupings tries to diagram. As tech companies approach the question of how to make livable cities “for all humans,” they may conclude that “organized complexity” — the problem of conceptualizing all those relationships — is just another problem of “big data” scale to be solved through the application of more processing power. Humans may be incapable of reproducing natural cities, but it’s only a matter of time, the thinking might go, before artificial intelligence will be able to do it. After all, Google’s translation algorithm recently produced its own language.

This emerging structure of the city compels us to chase speed and upgrades. It’s as if it has become conscious and is trying to assimilate us to its cloud

Yet looking to artificial intelligence to simulate the complexity of cities merely reiterates the problem of organized complexity rather than solve it. The processes that developed the natural city were initiated by humans, just like Google’s translation AI, yet we don’t know how to replicate those processes, and we can’t predict what we’ll end up with if we try. What was once understood as arbitrarily designed becomes a given, like nature.

Alexander’s view of “nature” resembles that of French poet Paul Valéry’s: “Whenever we run across something we do not know how to make but that appears to be made, we say that nature produced it.” Or, as Karatani summarizes it, nature “indicates everything we do not know how to make,” including things that are made by humans, like cities. When humans create suburbs, the result may feel like death to some, but once these environments are made, they have a life of their own and develop their own chartable complexity — they become “natural.” Once in motion, they appear irreversible, since humans themselves are bound up in these emerging natural orders — as Karatani writes, “the structure of the natural city thus emerges from the consciousness of the ‘subject living in the city’” — and transform with them. A city designed by artificial intelligence would probably be just as natural, and inscrutable.

The problem with potential “smart cities,” then, isn’t human inability to produce “natural cities,” but rather what happens to humans in the process. Just because a housing development evolves into something natural doesn’t mean it inevitably improves on past conditions. Most technological shifts appear inevitable after the fact, as they become part of the grand narrative of human progress, but hardly any significant societal shift has been optimal across the board. For example, in Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, Yuval Noah Harari argues the agricultural revolution was not “a great leap forward for humanity” in which people learned “to decipher nature’s secrets, enabling them to tame sheep and cultivate wheat.” Rather, this shift was irrational, accidental, and left many humans worse off than before: “The agricultural revolution certainly enlarged the sum total of food at the disposal of humankind, but the extra food did not translate into a better diet or more leisure. Rather, it translated into population explosions and pampered elites. The average farmer worked harder than the average forager, and got a worse diet in return.” As a result, Harari notes, “We did not domesticate wheat. It domesticated us … wheat has become one of the most successful plants in the history of the earth … Wheat did it by manipulating Homo sapiens to its advantage.”

Virtually every subsequent historical and technological shift fits this pattern. Everyone who’s experienced the digital revolution can probably relate to Harari’s claim about agriculture: “We thought we were saving time. Instead we revved up the treadmill of life to 10 times its former speed and have made our days more anxious and agitated.” Smart cities portend similar consequences.

Why do we stick to new practices if they lead to worse conditions? Harari offers two possibilities. One is path dependency: the negative effects that followed the agricultural revolution emerged over several generations; once they did, everyone had adapted to the new ways, and there was no longer any living memory of the old ways. The second is a conception of history as driving toward the unity of all humans. The agricultural revolution may have made it harder for individuals, but it made it possible for more people to share worse conditions together.

Given the racist and fascist currents in the political climate, the idea that the history is moving toward global unity may seem hard to credit. But though political or ideological unity may not be in the cards, it certainly seems the world is rapidly becoming integrated within the same economic, technological, and networked system of speculative digital capitalism. You can buy Coca-Cola in every country except North Korea, more than half the world’s population now use the internet, and a financial crisis in the U.S. reverberated across the globe.

Facebook aspires to be another of these global systems of interconnection. Its mission statement is to “bring the world closer together,” and its founder believes the solution to global inequality is to get “everyone online and into the knowledge economy.” No other global organization, company, or internet platform has ever come as close as Facebook to forming something like a global, virtual government.

Facebook’s efforts go hand in hand with those of other global tech companies. Right now, the fastest growing of these are working on increasing the speed and efficiency of transporting goods, people, and information to, from, and within cities. Ninety percent of all of our transactions are now electronic; the cash we use is so minuscule in comparison it’s barely noticeable. This process isn’t driven entirely by tech companies in top-down fashion, though. The internet set new standards for speed of exchange and economic growth, and it seems every person, building, and vehicle yearns for the upgrades that will enable them to catch up or keep up. This emerging structure of the city compels us to chase speed and upgrades. It’s as if it has become conscious and is trying to assimilate us to its cloud.

If the architecture of cities once helped unleash capitalism, it now seems that architecture itself has been domesticated by it. Then again, perhaps the cycle has always worked this way. For Karatani, Western thought is defined by a “will to architecture that is renewed with every crisis — a will that is nothing but an irrational choice to establish order and structure within a chaotic and manifold becoming.” Similarly, Pier Vittorio Aureli summarizes the history of architecture as the process of subjecting humans to ever more abstraction. In fact, the reduction of human life seen in Howard’s concrete villages and Corbusier’s machine à habiter started long before, with the monastery.

More than just a place for prayer, monasteries were built to manifest and spread the form of the religious ideal by enforcing religious life. As an apparatus “aiming to regulate life in all its physical and mental aspects” to conform with ascetic religious ideals, monasteries excluded the symbols, traditions, and social codes of other forms of life, and imposed a new, simpler form by designating a specific space for each type of activity: “dormitory (sleeping), refectory (eating), library (studying), workshops (working), chapel (praying).”

If the monastery imposed a new form of life, produced a new kind of human, it was because monks and nuns sacrificed parts of their own semantic universe and integrated themselves into the architecture and social codes of the monastery, filling it with life and meaning. Over time, the monastic model — of bringing large numbers of disparate people into the same enclosure and subjecting them to regulated, repetitive activities — became the model for schools, asylums, army barracks, poor houses, orphanages, and prisons. It also gave rise to a new form of manufacturing, and conceivably unleashed “labor as such” — the idea that workers are interchangeable, which was fully realized with factory labor.

The architecture of the factory further materialized the abstraction of labor and compartmentalized the individual. A very influential example is Albert Kahn’s 1909 design for a Ford Motor plant in Highland Park, Michigan, which introduced the assembly line. Like the monastery, the factory required humans to integrate themselves into, adapt, and make sense of it, which was never a smooth process, often leading to worker’s strikes and rebellion. But this too, writes Aureli, contributed to “relentless scientific abstraction”: “The more workers rebelled against work, the more capitalists were forced to improve the efficiency of workers’ exploitation. For this reason within the daylight factory amelioration of working conditions and further exploitation of workers were the two faces of the same coin.”

The process of integration might be violent and disruptive at first, but over time the new order emerges as something natural. As Kiarina Kordela argues in $urplus:

The more rationalistic a discourse is, and the more it demands from its subjects to accept science as the ultimate truth, the more semantic sacrifices the subjects are forced to make in order to find an answer to these, officially illegitimate, questions of metaphysical justice. And the more the subjects are forced to take upon themselves the responsibility for the discourse’s inconsistency, the more non-coercively does the discourse sustain itself and its authority.

The total rationalization of discourse that Kordela refers to seems to coincide with the moment that abstraction (or commodification) of thought and abstraction of architecture merge: first with the rise of mass education, and then with the expansion of knowledge work, freelance labor, and startups. As Aureli summarizes, “when knowledge and information are bought and sold as commodities, universities are centers of production.” Students don’t just absorb specific skills or forms of knowledge, but “learn how to live, network, and compete. In this way the university becomes an edufactory empowered by the mass production of subjects ready to be implanted into the increasingly precarious conditions of work.”

Just as factory designs came to dominate entire cities, we’re now seeing the principles of the edufactory envelop the entire knowledge industry, reshaping cities to accommodate life-long learner-freelancers. In terms of abstract architecture, this sort of smart city manifests itself not necessarily as a mesh of interconnected “internet of things” devices but rather in the form of university campuses, startup villages, and co-working spaces where large, flowing halls connect academic departments, dorms, recreational facilities, shops, and cafeterias, thereby collapsing traditional boundaries between work and leisure, studying and networking, production and consumption, research and entrepreneurship, designer and end-user, public and private life.

This kind of space, Aureli suggests, “reflects the state of precariousness” of the “dislocated researcher whose self-promotion is the result of the lack of economic support and social security.” On the surface, their “openness and self-organization” seemingly promote “‘progressive’ tendencies, but in fact enact capitalism’s total exploitation.” This suggests that our existence and self-promotion on social media networks like Facebook has nothing to do with narcissism but rather with insecurity. Just as wheat and abstract architecture domesticated humans, so has social media. Our lives become subjected to the demands of our profiles.

Today, the city is being transformed so quickly by independent developers, tech companies, and ever-emerging trends, the theories of urban planners on how to best build a city are becoming irrelevant. However abstract and imaginary the principles governing it is, they come at us with force, and we struggle to catch our breath and reconstitute ourselves between work shifts, panic attacks, and general confusion. Franco “Bifo” Berardi locates this feeling in the networked urban territory, which he calls a “city of panic.” He writes, “we can speak of panic when we see a conscious organism (individual or social) overwhelmed by the speed of processes in which it is involved, and where it has insufficient time to handle the information generated by those processes.”

Collective expression of rage offers a way out of the schizophrenic-like condition that the future of urban life offers

How far can this go? How long before this process of “compartmentalization” and “dissociation of internal elements” leads to a complete breakdown of its subjects, as Alexander predicted? Is the feeling of powerlessness a symptom or a cause of our condition? Even if we’re able to retain some semblance of sanity, remain conscious and critical, for many of us it seems as if our consciousness has no bearing on our reality beyond holding on to a sense of self. As Berardi writes, at this stage of capitalism, “the consciousness of the process does not belong to the process itself.” The best we can do with it is commodify our thoughts on social media, which only further entraps us.

Referencing Gregory Bateson’s Steps to an Ecology of Mind, Karatani compares this double-bind situation to the experience of schizophrenics:

In Zen Buddhism there is a style of teaching in which the master holds a stick over the pupil’s head and says fiercely, “If you say this stick is real, I will strike you with it. If you say this stick is not real, I will strike you with it. If you don’t say anything, I will strike you with it.” … With Zen, the pupil chooses to be in this undecidable situation; moreover, the student might even reach up and snatch the stick away from the master … Schizophrenics constantly find themselves in situations like that of the pupil. But for them, there is no escape.

For many urbanites of the 21st century, too, it may seem as if there is no escape. The only reprieve is having access to enough resources to buy yourself time, privacy, and space to reflect — something once abundant but now scarce for all but elites. For everyone else, it’s possible the future of urban life turns into de facto schizophrenia. Karatani summarizes four ways the schizophrenic tries to handle double-bind situations:

- Shifting the mode from the literal to metaphorical. Basically, taking everything ironically, like a joke.

- Becoming obsessed with “hidden meanings,” setting out to prove “they will never be tricked,” and approaching everything with paranoia and distrust.

- Reject all meta-communication and receive every message literally.

- “Ignore everything in an attempt to avoid situations that require responses.” Abandon “all interest in the outside.”

At one point, these behaviors may have sounded “sick.” Today, they may seem like strangely familiar, if not standard coping mechanisms for a perpetual state of anxiety.

There’s coping, and then there’s fighting for a way out. Even though capital’s domination of space feels total, it continues to be contested. People pee on the walls of police precincts, they burn gas stations, tear down statues, and break retail store windows. Collective expression of rage and rebellion offers a way out of the schizophrenic-like condition; in its complete disregard of structured time, movement, and control, the riot reintroduces self-referentiality — the sense of being an autonomous self in control of your body — that a state of precarity forecloses.

But if it’s true that factory rebellions led to the extension of abstract labor to all of society, we have reason to suspect future cities will seek to completely prevent riots. This may feel and look like the oppressive totalitarian states we’ve been taught to anticipate, a dystopic tech-driven panopticon. Or as Kordela suggests, it’s possible a more total form of control will feel less coercive than what we have today. It might look something like the world depicted in the French-Israeli live action/animated sci-fi film The Congress, where artificial intelligence has automated even creative, artistic labor, and people breathe in chemicals to enter animated zones and become cartoon versions of themselves. Over the years, the un-animated world turns into a wasteland of disassociated junkies, with very few people choosing to stay in the “real” world.

In some ways, we’re already there. The animated avatars of The Congress look almost identical to those of Facebook’s VR initiative Spaces. Unlike most other virtual reality developers, Facebook’s VR platform isn’t focused on gaming but on creating a space in which people can hang out across geographical space. It is not marketed as an escape from reality but a place to “be yourself,” “hang out with friends,” and “create memories.”

The supposed appeal of Spaces is that it completely merges the virtual and the physical. This may be foregrounding the nature of cities to come, as the world’s unfolding increasingly plays out on what the Dutch research and design studio Metahaven calls the “surface” — such things as social media and messaging platforms, email, live streams, search engines, online retail sites, and so on. As Metahaven writes,

The city becomes the profit base of a virtual spin: the multiplication of surface accounts for the exponential growth of value extracted from its public space. By our being in public, by simple existence, we already automatically affirm the exposure which grants the surface infrastructure its right to the city. The inhabitants of cities are, through this mechanism, directly inscribed into the means of value production.

Facebook’s planned cities may turn out to be a way to make physical territory universally operate as surface. It may seem counterintuitive to shift attention to the inner workings of the city when the economy, politics, and cultural discourse seem to increasingly play out on the internet. But it’s not. There is no separation, only untapped surface potential.