“There is no right or wrong in Proust, says Samuel Beckett, and I believe it. The bluffing, however, remains a grey area,” wrote Anne Carson in The Albertine Workout. There may be no right or wrong in Proust, but there is a right or wrong way to say “Proust.” I learned this the hard way, during a grad school seminar, when I pronounced the name Pr-ow-st in the above-quoted. My professor quickly interrupted: “You better learn how to say Proust before you graduate, or you’ll be an embarrassment to yourself and the entire school.”

When I was a child I did not know how to talk. Or rather, I knew how to talk but couldn’t. My words came out garbled and unintelligible, frustrating both for the person trying to decode what I meant and for myself. In a home video I hold a snail between my thumb and index finger and confidently repeat the word nell over and over, while the floating voice of the person filming repeatedly asks What? I compile my own language by repeating the first syllable of a word twice: barbar. The test scores at age three landed me in the bottom rung for articulation, indicating “a severe phonological disorder.” Followed by a reassurance: “Intelligibility of her spontaneous speech was fair when the context was known.”

I was placed in therapy with Susanne, a speech pathologist, once a week. We played handmade board games and read books, stopping periodically to break words into syllables and for me to mimic the movements of Susanne’s mouth and tongue. Today, the reminiscent effects of my phonological disorder are often unnoticeable: my spelling is awful, sometimes my r’s slip into w’s (referred to as the gliding r); after years of not speaking I now say too much, talking simply because I can, rather than to say anything important. Of all the continued effects that my speech impairment has had on my life, it is the risk of mispronouncing words that embarrasses me the most.

Learning to say a name out loud is a skill that begets inclusion. In an academic setting it offers inclusion into a specific discourse. In conversation with another person, it shows respect

To say something correctly is work — first you must know how the word is supposed to sound, and then, whether the skill is innate or learned, you must know how to mimic the sounds with your tongue. The process of learning how to say a word is uncomfortable: Your tongue moves in a way that doesn’t feel natural. It is only by listening, repetition, and practice that a word stops feeling strange in your mouth. To put the work into saying someone’s name correctly is a sign of respect. Saying a respected name properly also affects how others perceive you. Confidently letting Proust roll off the tongue signals one’s intelligence; pronouncing it pr-oo-st shows your know-how and comfort within a certain discourse.

Not everyone’s name is afforded the same effort. Professors who insist on the correct pronunciation of French philosophers regularly fumble with names of students whose names do not sound European-derived. During the 2015 Golden Globes, when Ricky Gervais mispronounced Quvenzhané Wallis’s name, his response was to shift the attention to John Travolta who had mispronounced Idina Menzel’s name the year before. During the 2014 Academy Awards, Neil Patrick Harris repeatedly said Chiwetel Ejiofor’s name wrong. The way that names are pronounced or mispronounced often reinforce racist cultural values.

I can attest to the difficulties of pronouncing words. What I know for certain is that pronouncing a word properly is a work requiring care and attention; the words that individuals choose to apply their labors to demonstrate a power imbalance that lives outside of phonetics.

Since people could never understand what I was saying, I was forced to find multiple ways to articulate simple explanations, which helped my ability to write a sentence. Reading was always preferable to conversation, so I did a lot of that too. I am not alone in choosing to socialize through text instead of in person, an impulse shared by many who live online and congregate over social media. While the internet has the ability to connect people, the majority of correspondence is written, rather than auditory. The result is the possibility that you have no idea how to pronounce the name of an e-friend, or they yours. A name can be an essential characteristic; a name’s pronunciation is a physical property. To lack that knowledge creates more distance.

When faced with an unfamiliar name or letter placement we revert to the language we know best to suss out the pronunciation. But each language feels different when spoken; the placement of the tongue shifts dramatically. In English, the width of the tongue is kept narrow, to avoid touching the teeth. Slightly retracted, with the tip raised. Correct pronunciations might seem obsolete as long as you’re reading words on a screen, and yet text-to-speech programming is notorious for its incompetencies: Speech synthesis relies on hours of isolated sounds of natural speech, which is then rearranged into diphones (two sounds together). Yet we don’t speak in simple diphones, especially with names, as Christopher Mims writes for MIT Technology: “Some words are collections of sounds unto themselves, and diphones common to two words might not sound right in a third, which could require a triphone or even something more.” Simply put: there’s nothing that can replace the physicality of a name on the mouth.

Learning to say a name out loud is a skill that begets inclusion. In an academic setting it offers inclusion into a specific discourse. In conversation with another person, it shows respect. If all you’ve ever done is read a name, there’s the potential you’ve been saying, or rather, thinking, the word wrong the whole time. Learning the correct pronunciation then becomes an act of acknowledging a vital part of another’s identity — not just the identity that is most easily placed on them.

In her poem “the birth name,” Warsan Shire, a Somali poet living in London, writes:

Give your daughters difficult names

give your daughters names that command the full use of tongue

my name makes you want to tell me the truth

my name doesn’t allow me to trust anyone that cannot pronounce it right

What does a name mean? The branch of study that deals with this question, onomastics, works to find the origin and history of proper names, while anthroponymy studies human names specifically. Anthroponymy is the reason I know the answer when someone asks me what my name means: “one who brings cheer to others.” I relate less to the meaning than the actual name, which has been mine as long as I’ve lived. When people mispronounce Tay-tum, it ceases to feel like me.

Mispronouncing a name tells the other person not only that you couldn’t be bothered to acknowledge their identity, but you intend to subject it to your own

In an interview by Kameelah Janan Rasheed for The Well & Often Reader, Shire writes:

Warsan means “good news” and Shire means “to gather in one place.” My parents named me after my father’s mother, my grandmother. Growing up, I absolutely wanted a name that was easier to pronounce, more common, prettier. But then I grew up and understood the power of a name, the beauty that comes in understanding how your name has affected who you are. My name is indigenous to my country, it is not easy to pronounce, it takes effort to say correctly and I am absolutely in love with the sound of it and its meaning. Also, it’s not the kind of name you baby, slip into sweet talk mid sentence, late night phone conversation, whisper into the receiver kind of name, so, of that I am glad.

The National Education Association considers the mispronouncing of names to be akin to an act of bigotry. “Names holds ancestral and historical significance for many minority, immigrant and English learning students. Names bring stories, which students are often forced to adapt to an ‘Americanized’ context,” writes Claire McLaughlin in her essay “The Lasting Impacts of Mispronouncing Students’ Names.” She continues, “That transition, however, is often painful and forces many students to take on names that are not their own.” Durga Chew-Bose, in her essay “How I Learned to Stop Erasing Myself,” considers the greater implications when a name is silenced: “When it comes to our identity, the ways in which it confuses or interests others has consistently taken precedent as if we are expected to remedy their curiosity before mediating our own. In this way, I’ve caught myself disengaging from myself, compromising instead of building aspirational stamina.”

If mispronouncing a bourgeois term leads to embarrassment, then the imperative to pronounce it properly demonstrates an imperialistic form of cultural power. If mispronouncing a non-European or non-“Americanized” name is met with ambivalence, this too reflects an arrangement of power, and demonstrates a value structure. Persistent mispronunciation is related to what Édouard Glissant was referring to when he examined language as a site of conflict. Language is one of the first things that colonizers subject on the colonized, knowing that, “he suffers most from the impossibility of communicating in his language.”

Mispronouncing a name becomes purposeful — it tells the other person not only that you couldn’t be bothered to acknowledge their identity, but you intend to subject it to your own.

To return, again, to Anne Carson’s The Albertine Workout: “given Marcel’s theory of desire, which equates possession of another person with erasure of the otherness of her mind, while at the same time positing otherness as what makes another person desirable.” To subject a name to one’s own pronunciation is an attempt to erase the otherness of another. As Chew-Bose writes, “I now know that something far more furtive is at play when one’s name is misheard, that the act of mishearing is not benign but ultimately silencing. A quash so subtle that — and here’s what I’m still working out — it develops into a feeling of invalidation I’ve inhabited ever since I was a kid.”

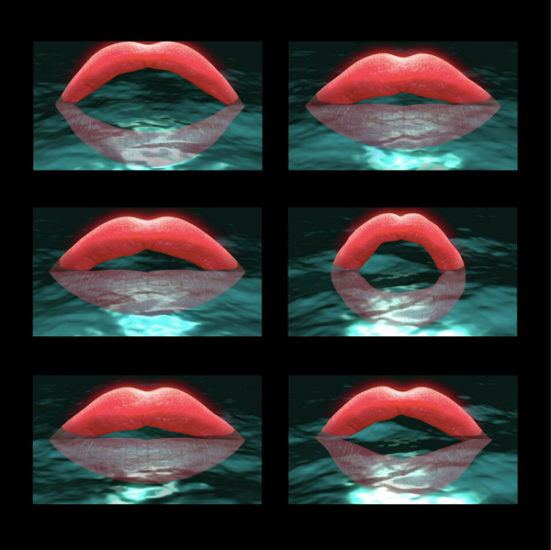

Correct pronunciations are something one has to learn: there’s a physicality and practice involved in learning to say “Nietzsche,” which confers a distinct cachet within the dominant culture. If you can learn how to say Nietzsche, you can learn to say Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. It’s one thing to know how to spell a name, to recognize it on a screen, to repeat it in your own head in a way that makes sense to you. It takes more work to pronounce a name out loud and correctly — to utter a name as it is, to acknowledge the person it belongs to. Perhaps we should be observing the shape a mouth takes when a name is on the tongue.