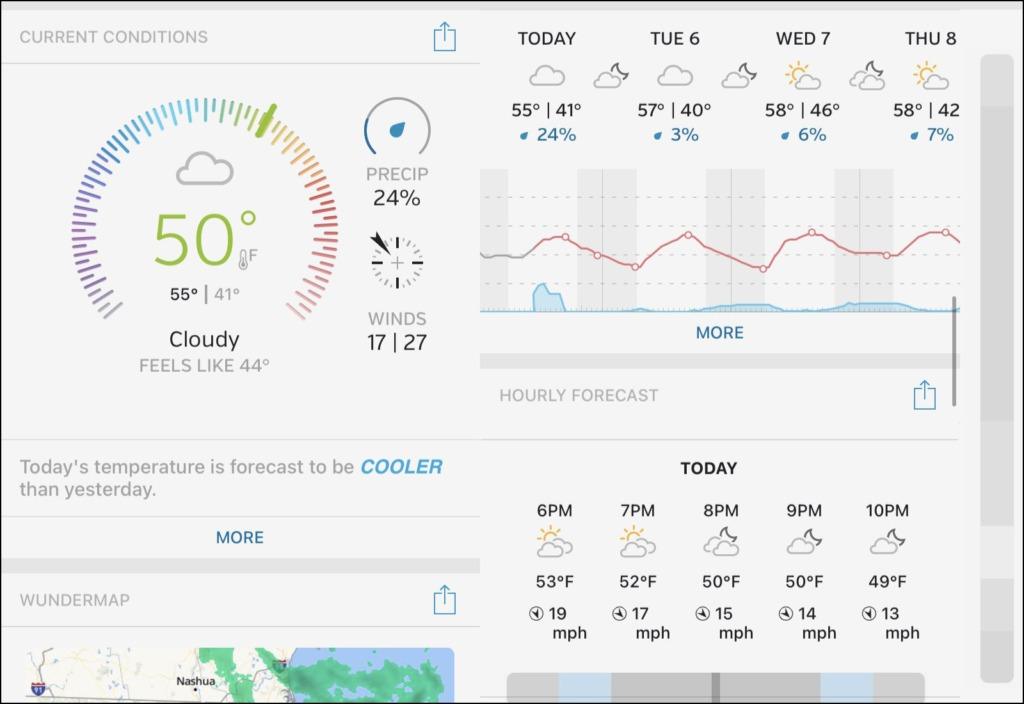

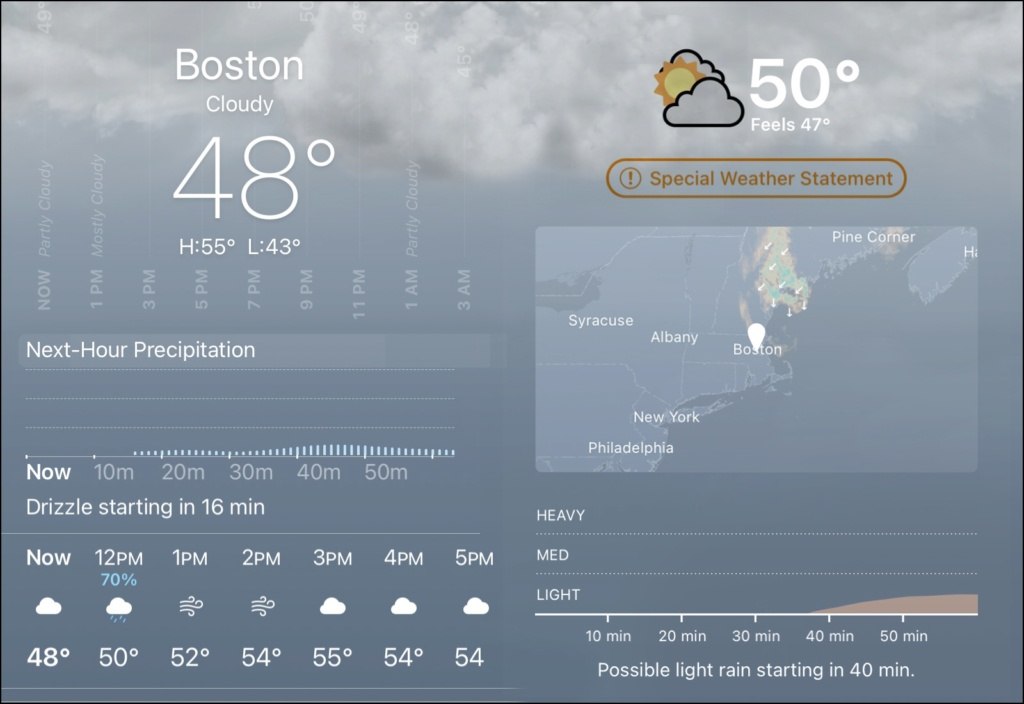

On a cloudy morning in April, a weather app called Dark Sky alerts me of “possible drizzle starting in 12 min., stopping 7 min. later.” Below that missive is a bar graph of the next hour, its only deviation from a baseline of dry conditions a slight, blue hump indicating when said drizzle is most possible. When I check again a few minutes later, Dark Sky has revised its estimate, now saying that the rain may begin in 40 minutes. The Weather Channel-backed app that came preloaded on my iPhone — which is elegantly called “Weather”— disagrees, saying the rain will actually begin 16 minutes from now. In lieu of a minute-based prediction, Wunderground says that there’s a 40 percent chance of precipitation at noon, but that only a hundredth of an inch will accumulate. Weather says the temperature is 48°. Both Wunderground and Dark Sky say 50°, though one says it “feels like” 44°, the other 47°.

You can spend an hour on these weather apps and have no more sophisticated a takeaway than, “it’s nice out,” or, “better bring an umbrella”

All of this comports with an early spring day in Cambridge, Massachusetts: The sky is gray, the boughs of the hemlock tree outside my window quivering in the breeze. I crack the window, and the air is chilly, but not intolerable — a decent sweater, a light jacket, and a beanie should suffice for the walk to the market I’d been planning, but am now rethinking, given the impending drizzle. I check my phone again, and all the forecasts have shifted. Weather has already abandoned the 16-minute prediction, saying now only that there is a “chance of drizzle in the next hour.” Conversely, Dark Sky has gotten more aggressive, promising that the rain that comes will be “light” rather than a mere drizzle. The app is so confident that the monotonous gray of its hour-by-hour “mostly cloudy” forecast, which takes the form of a bar of colors rather than a chain of illustrations, has been interrupted by a band of blue.

A wind chime is jangled by the breeze, so I look up to see if conditions have worsened. The hemlock rustles. The sky remains gray. A child on a scooter jets down the sidewalk toward the park on the next block, accompanied by a bored-looking babysitter. Once I finally rouse myself and go out walking, all the data I’ve consumed vanishes from mind. It’s gloomy out, chilly. The sun peaks out between the clouds. When the wind picks up, I zip my jacket. The rain is neither light nor drizzly: It never comes.

However quantifiable weather may be, no calculation or map can provide a substitute for an individual’s experience any given day. There may be as many perceptions of a sunny, 63° day as there are people, but even the broad consensus of how that sunny, 63° day feels will differ greatly by region, with Southerners labeling it “chilly” while Upper Mid-Westerners consider it “balmy.” Even as weather apps track the most minute variations on the day’s temperature, their data-heavy objectivity, no matter how detailed, still makes them about as useful as the static newspaper forecasts of yore, which would sum up the day’s weather with a few lines of copy, the day’s high and low temperature, and a graphic indicating the prevailing conditions. Though the capacity of meteorologists to predict the weather has gotten infinitely more sophisticated in the digital age — the NOAA now says that its five-day forecasts are 90 percent accurate — presenting the full spectrum of data that previously served merely to generate a condensed forecast is hardly more informative than a local TV broadcaster proclaiming, “It’s gonna be a hot one!”

Wunderground’s interface is made to look like a car dashboard, the foundational elements of location, temperature, and current conditions packaged together into a speedometer dial, with two smaller gages (the tachymeter and gas meter, say) noting the direction and speed of wind, as well as the current chance of precipitation. The Weather app takes a slightly more aestheticized approach by illustrating the current conditions with a nifty little animation of floating clouds or falling rain behind the temperature reading, while Dark Sky is more restrained, with its grayscale timeline of the day, the only colors an occasional pop of blue for rain or yellow for sun.

The deeper one digs into these apps, the more informative they get. Dark Sky and Wunderground have interactive maps that fill up with low-pressure fronts, satellite cloud imagery, and temperature gradients as different buttons are toggled, while Weather includes data on air quality — represented by a prismatic bar extending from healthy green to lung-scorching maroon — and the UV index, a single number that distills the shifting interplay of sunlight, clouds, and ozone. Each app offers the full make and measure of the day, even as most users are content to know only if it’s too warm for a jacket or if a snowstorm is approaching. There’s a deep discrepancy here: No matter how much data must be marshalled to create even the most benign weather forecast, being presented with that data does little to deepen one’s understanding of the forecast itself. You can spend an hour on these weather apps and have no more sophisticated a takeaway than, “it’s nice out,” or, “better bring an umbrella.”

However seemingly quotidian this schism between weather as data points and weather as a thing that you can feel on your skin, the divide’s most worrisome ramification is in the inability of individuals living in comfort in the United States or Europe to perceive climate change as an event they are experiencing rather than just another crisis they read about online, as horrific and irrelevant to their life as the military coup in Myanmar or the emergence of the Islamic State in Sub-Saharan Africa. No matter how many times one studies the Keeling curve or pairs its arc of ascending carbon-dioxide levels with global temperature rise, connecting that data to the weather as it is experienced day-to-day is nearly impossible. No, it’s only ever through disastrous events like Hurricane Harvey or Typhoon Goni that the connection between weather and climate is intuitively felt.

When Hurricane Sandy hit New York City in 2012 I understood that the storm’s historic strength was a symptom of climate change, even as spending the night listening to wind rattling window frames in Brooklyn produced in me a visceral and immediate terror. That night felt like weather, while the days that followed took on an aura of climate, mostly thanks to the physical effects of that storm — the downed trees, the inability to visit Manhattan for a month — which reordered space in an unprecedented way.

Climate change’s most salient manifestation is not in extreme weather itself, but rather the moments when that extreme weather overpowers our decaying infrastructure by flooding tunnels, overpowering dams, or spreading Valley Fever on arid wind. In an earlier era, the hurricanes, rainstorms, and droughts that cause these sorts of disasters would be described as cruel acts of god; given the contemporary replacement of faith with reason, weather catastrophes are instead understood to be a culmination of capitalistic excess, those who benefit least from the carbon economy also being those who suffer its consequences most acutely.

In recent years it has become common to refer to the conflation of these manifold social and ecological ills as the “climate crisis,” a phrase meant to convey the urgency of the situation. It’s a worthwhile rhetorical gambit, even as it fails to penetrate the membrane between knowing and feeling in a way that might make its exhortations ring true on a bright, sunny morning or amid a delightful New Year’s snowfall. However harrowing they may be, crises are typically understood to be things experienced at a distance. The financial crisis, the mortgage crisis, the Cuban Missile Crisis — these scary-sounding troubles are only felt once you lose your savings, your home, your sense of remove.

What few methods we have developed for describing climate change are drowned out by the far longer tenured language of weather, a language that is intertwined with our emotional life. What’s lacking is a sense of the climate crisis as a thing that can be felt equally intuitively. Not only do feeling and knowledge stand apart from each other, all too often each is used to explain the other away. (One may understand the mechanics of precipitation perfectly, but rain still just feels like rain. Neuroscientists may be able to map the firing of electrons within the brain of a depressed person, yet when the researchers themselves get sad they simply feel sadness.) This divide would be incidental, had weather not become a symptom of an existential threat.

One of the few moments in recent years when feeling and knowledge indelibly intertwined was last fall’s orange-sky day in San Francisco, when various measurable climactic and societal factors — smoke from the beetle-desiccated trees that were burning in record numbers across California’s poorly managed forests, hellacious winds, and a foggy Pacific marine layer moving inland — all conspired to briefly transform reality into dystopian science fiction. No rhetorical flourish is necessary to illustrate the climate crisis under such circumstances. If you lived in the Bay Area on September 9, 2020, the crisis was all you could see.

Such moments, though, are fleeting, and extremely localized. The equivalent of an orange-sky day on the East Coast probably looks more like Hurricane Sandy; across the Midwest like the never-ending spring rains that cause rivers to overpower their banks. Scientists can explain how all these catastrophes are interrelated, but it is imperative that we also develop the capacity to experience them that way. To know and feel in tandem, as a singular response.

The alienation between people and the scientific observation of climactic conditions is as old as language itself. The novelist Karl Ove Knausgård notes our reliance on the impersonal pronoun “it” when describing the weather:

“It’s raining,” we say, “it’s blowing” or “it’s snowing.” But what exactly is doing the “raining,” the “blowing,” the “snowing”? The rain is, the wind is, the snow is; the actions are their own agents, conflated with the subject. “It” points toward a force that exists outside of us and over which we have no control.

While traditional meteorological forecasting made no secret of that lack of control with its vague, existentially ambiguous language (“snow possible overnight”), contemporary apps are built to trick the user into perceiving the weather as a thing that can be skillfully navigated; the weather is hardly more possible to master than the Pacific Ocean, but with the right set of tools, the indoor dwelling weather-watcher can chart a course for maximum comfort in the outdoors. It will start raining in 24 minutes and then stop after two hours? Why, then I’ll pop out for a quick walk now, and save my trip to the grocery store for later!

The notion that the weather can be forecasted so intimately — especially days or weeks ahead of time — is laughable. “It may rain in the afternoon” and “it will begin raining in 18 minutes” are both attempts to turn probability into language, their relative authoritativeness meant to broadcast differing levels of certainty. That weather predictions can be right 90 percent of the time is a feat of science, but when that hit rate is tested literally every hour of every day, 10 percent of forecasts being wrong is hardly an incidental proportion. And if a gap in the clouds means one town misses out on the blizzard that blankets an entire region, was the snow forecast wrong? Or merely too sweeping? In any case, no matter how much more refined the discipline of weather prediction becomes, it will always be based on describing an “it” — action and agent, a conflation of forces that the human mind struggles to accept can truly act in a unitary way.

What few methods we have for describing climate change are drowned out by the more tenured language of weather, a language that is intertwined with our emotional life

This may be why some meteorologists have traded daily and weekly weather prediction for climate change forecasts, which seek to predict the toll rising temperatures will exact around the world. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change is the most prominent of the groups doing this modeling, though even the most alarming predictions in their 2018 report were couched far too firmly in the language of science to produce an affective response. Global temperatures rising by 2°C would cause 13 percent of ecosystems to “undergo a transformation,” the dozens of researchers who contributed to the report wrote, before going on to also warn that reaching that threshold would cause the Arctic to have an “ice-free” summer at least once per decade. These are measurements of an “it” to come — they say little about what it might feel like to live in an ecosystem undergoing such a transformation, like on Ellesmere Island in June.

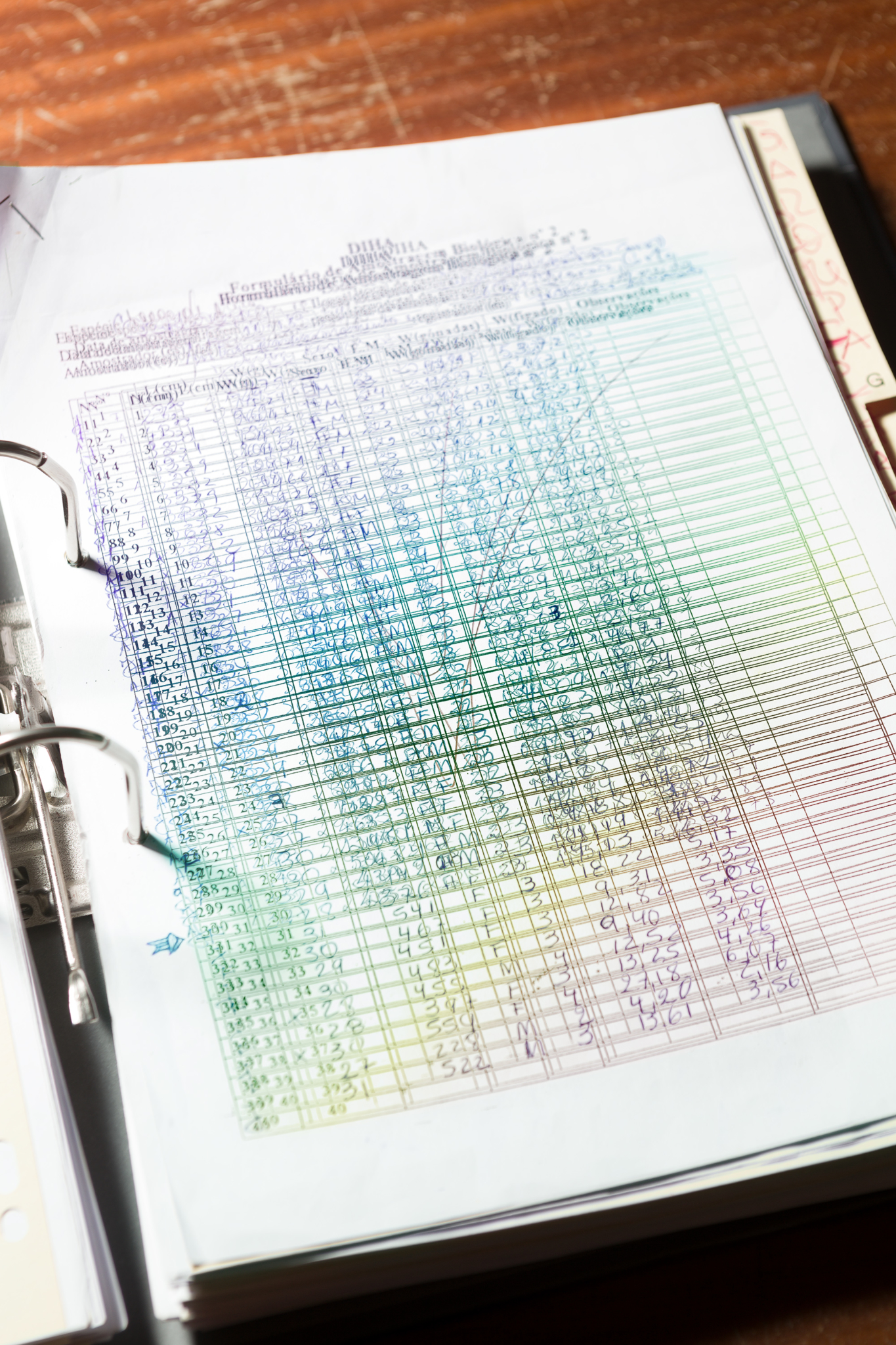

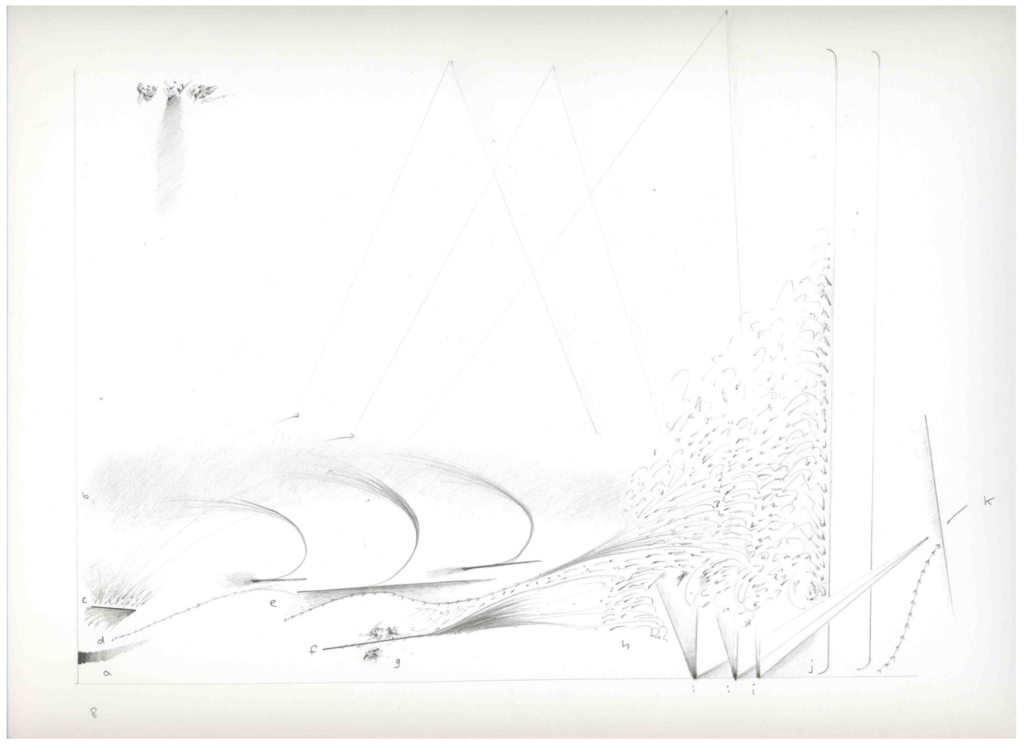

In Subjective Meteorology, the artist and academic Johanna Drucker attempts to use meteorological techniques to map the way her emotions vary from day to day. “The forces of wind, heat, temperature gradients, relations to terrain and physical features vary at every level of granularity within the atmosphere,” Drucker writes. “My fascination with this as a set of metaphors is absolutely, firmly based in the belief that the subjective experience of daily life can only be described in such a system with all its exhaustive repleteness.”

Casting weather events as metaphors is antithetical to the approach of meteorologists, whose sophisticated ability to marshal data means their work is firmly scientific, rather than figurative. But Drucker is right: The very act of translating a weather event into language is an act of metaphor making — without an ability to disentangle action and agent, we resort to the signifier of “it’s snowing.” The same goes for emotion. The phrase “I’m angry” is an expression of internal conditions that are otherwise impossible to articulate.

Drucker’s project aims to refashion that continuum into a single visual language, but to do that she needs to break down the border between the “I” who feels emotions and the “it” that causes weather. “The ‘I’ of subjective meteorology does not ‘have’ experiences,” she writes. “Instead, the ‘I’ is like the eye of a storm or system, moving and volatile, a dynamic zone of pressure, arising from the conditions in which it participates as an autopoetic agent intervening in a field of potentiality.”

The system Drucker comes up with to capture “subjective meteorology” consists of the same components that make up the scientific field: atmosphere, topography, dynamics, and rules of behavior. Her illustrations of that system rely on familiar weather map figurations, “fronts” and “perturbations” that demonstrate where in her mind-space the components are meeting and causing havoc. The personal weather maps that result are far more dreamy and evocative than what you might see on the seven o’clock news (or, indeed, thumb over on the Wunderground app), yet still manage to articulate Drucker’s daily moods in a radically different way from what language alone could manage.

Day Eight: a) waking without recollection of dreams; b) proximate condition of rain; c) densely concentrated activity; d) work against pressure; e) backwash against resistance; f) resistant line; g) short conversations; h) productive and critical confusions; i) windows toward possible futures; j) bracket of social space; k) trajectory of resolution towards anticipated limit.

In one of these sketches, an “upswelling of dark moods” runs into “engagement of exchanges in energy,” which is represented by an airy column pointing heavenward, where it eventually meets a wispy arc of “energy rising towards anticipated endpoints.” On a different day, three V-shaped spouts — “windows toward possible futures” — draw in a cloud of “productive and critical confusion” and redirect it on a “trajectory of resolution.” These drawings are best understood as a formalized attempt at abstract expressionism. Some lines are dark and firm, others wavy and nearly immaterial; all are meant to harness mood and make it visual. In their two-tone composition, they echo Franz Kline’s paintings, albeit in elegant pencil rather than his bold swaths of black pigment.

As with any work of abstract expressionism, determining just what Drucker means by a phrase like “engagement of exchanges in energy” is a tricky undertaking, one that would require knowledge of the infrastructure of her life to decode. (Does she have collaborators with whom this exchange is happening? Is the energy she’s describing personal or professional?) But Drucker is not writing a diary: The uncertainty created in the gap between her drawings and the glosses that accompany them should be understood as fleeting dispatches on her internal climate, unknowable to anyone but herself.

If I were to sketch how I experience climate change, it would look like a vortex of lightly struck hash marks, darkening in color until they terminated in a single, black dot

When Hurricane Sandy knocked the New York subway out of commission, the East River had to be reclassified in the brain of every Brooklynite. Rather than a natural feature that was nice to look at while riding the Q train into Manhattan, a mere element of scenery, the river became a physical barrier, effectively impassable. If “climate” is best understood as infrastructure transformed by weather, then Sandy’s effect on the internal climate of everyone living in the city in the fall of 2012 was just as profound as the erasure of Rockaway Beach. Only because our internal climates changed did the broader changes in the world’s climate become legible. It’s in this way that Drucker’s recourse to visual art proves so instructive. “Unseen, often unperceived, the complex exchanges of energy in human systems are always in flux,” she writes. “What we lack is a language to speak about these phenomena, or to represent them even to ourselves.”

Is it possible for an app to not only tell us the weather, but tell us the climate is changing in a way that we might feel as viscerally as a gust of wind biting the cheek? Perhaps a reading of 68° in Woodstock, Vermont, on December 25th would be paired with a flashing exclamation point that, once tapped, explained that the temperature reading was 16° higher than the previous record. Each time the app lit up with a notification about a hurricane bearing down on the Gulf Coast, would it be effective for the user to open it and find a scientific study demonstrating the causal link between ocean temperature and the flooding caused by cyclone-borne rain?

Even those approaches risk alienating users with their cold numbers and meteorological exactitude, which are little more than localized re-conceptions of the IPCC’s methods. A more affectively grounded outreach might play more to our senses — on March 26th of this year, what if every weather app had showcased videos of cherry trees blossoming in Kyoto, overlaid with text saying it was the earliest bloom in 1,200 years? What if every daily forecast in the states that lie along the Colorado River this spring was paired with live footage of the reservoir at Lake Mead, which is approaching the low ebb at which cuts to water use become mandatory? Would any of this help the user feel climate change on the personal level that might make them respond to the crisis accordingly, or would it just be more data that is easily pocketed and ignored once they were out in the world, enjoying some sunshine?

There’s an old nursery rhyme that goes: “We’ll weather the weather / whatever the weather / whether we like it or not.” With the onset of the climate crisis, that sing-song has taken on a dire tone. As long as our frame of reference is subjective, the weather will remain beyond our control, something that we can read forecasts about and feel on our skin but, ultimately, have no recourse against except forbearance. If I were to use Drucker’s system to sketch how I experience climate change, it would probably look like a vortex of lightly struck hash marks, darkening in color as they approached the center of the page until they terminated in a single, black dot: a point of terminal dread.

If climate and weather are to become one in our minds — whether unified in hopelessness or resistance, but with alternatives — it will surely be through short-circuiting the divide between feeling and knowledge. Art won’t save us from the climate crisis, but it can help us fuse the evidence of our senses and the output of the meteorological models in a way that allows them to be overcome in favor of an abiding understanding, one that might lead to different, more far-sighted behavior. If weather is action and agent conflated into a single subject, climate is that subject perpetuated on a global scale. To grasp it, we must reorient our own subjectivity accordingly. Close out the weather app, shutter the window. Go outside, pick up a pencil, and see if you can render how it feels right now, in this moment, to have the sun on your face and the oceans rising, a scent of spring flowers on the breeze and the rivers running dry.