In December, it’s common for writers to highlight some of their best work from the year in Twitter threads. Almost without exception, these threads seem laced with self-deprecating humor, irony, or, more often, some combination of both. A more matter-of-fact or even earnest tone was somehow not an option; instead what seemed required was a kind of ironic disavowal of disavowal with regard to our online presentation: The tone foregrounds the idea that we all must put on an act that fools no one. I was sympathetic myself. Truth be known, I didn’t post such a thread precisely because I didn’t think I could pull that tone off.

That tone’s peculiar kind of self-consciousness seemed to me connected to the anecdotes of depleted willpower that Anne Helen Petersen described in “How Millennials Became the Burnout Generation.” Take, for example, Tim, who could not quite manage to register to vote ahead of the 2018 elections, or Petersen herself, who admits to what she calls “errand paralysis”: “I’d put something on my weekly to-do list, and it’d roll over, one week to the next, haunting me for months.”

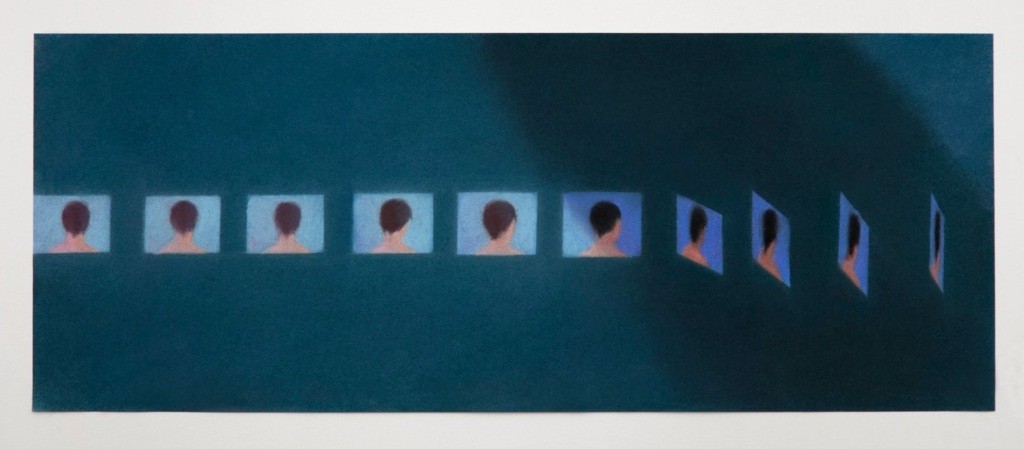

If writing had heightened consciousness to extend the self, newer technologies may heighten it to a point where it no longer sustains the self but undermines it

Millennials, of course, are not the first to feel a persistent sense of depletion. Among the historical antecedents, as Petersen notes, is neurasthenia, a nervous condition frequently diagnosed in the 19th century. Another antecedent is acedia, a combination of indifference, apathy, carelessness, self-loathing, and sleepiness that early Christian monks called the “noonday devil.” The term referred to an inability to get things done, especially the seemingly straightforward daily tasks it was a monk’s duty to perform, such as reading and prayer. Over time, acedia slipped loose of the monastery and was supplanted by words like sloth or laziness, although ennui may best capture its spiritual valence.

The self-conscious online tone is not exactly an expression of acedia in itself but could perhaps be seen as a leading indicator. Petersen suggests that social media platforms — she cites LinkedIn, Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter — contribute to burnout: They reinforce the idea that people should always be working by providing another arena for invidious comparison, self-branding, and optimization. But something more subtle may be happening as well. Social media platforms, like all technologies that mediate the self, “heighten consciousness,” in media scholar Walter Ong’s words. But if earlier technological developments, like writing, heightened consciousness to extend the self, newer technologies may heighten it to a point where it no longer sustains the self but undermines it.

Ong, a student of Marshall McLuhan, is perhaps best remembered for Orality and Literacy, his book about the social impact of the invention of writing on oral cultures. Writing, Ong repeatedly reminded readers, must be deliberately learned. “There is,” he notes, “no way to write naturally.” But this artificiality is not, in his view, a bad thing — far from it. “Alienation from a natural milieu can be good for us and indeed is in many ways essential for full human life,” he argued. “To live and to understand fully, we need not only proximity but also distance. This writing provides for consciousness as nothing else does.” By externalizing thought and expression, writing — the “technologizing of the word,” as Ong described it — distanced us from the flux of immediate experience and expanded consciousness into space and across time. The diary could be considered paradigmatic: It makes subjectivity an object of reflection, both in the moment of composition and for future readers as well.

Writing’s extension of consciousness has a direct effect on identity. As philosopher Robert Spaemann argued in Persons: The Difference Between ‘Someone’ and ‘Something,’ “the constitution of personal identity is inseparable from the process of self-externalizing.” This process, in his view, took place in recollection rather than direct experience. “It is memory,” he claimed, “that really reveals us to ourselves.” Spaemann was thinking chiefly of unaided or organic memory, but in Ong’s view, writing externalizes this memory work, encouraging and sustaining deeper self-explorations of the psyche and novel forms of self-expression. Just as a musician who interiorizes how to play an instrument can more fully realize the human potential for musical expression, likewise, Ong argues, the interiorization of writing allows for a fuller realization of human consciousness in general.

Social media platforms, like writing (or any other representational media), also externalize and heighten consciousness through self-alienating or distancing effects: To glance at your profile, to frame an image or message for posting, or to scroll through an algorithmically sorted feed is to see at least some aspect of yourself suspended in time and space. But the audience we address through these platforms, especially with communication broadcast to no one in particular, is quite different from the audience presumed by writing, let alone the interior audience of one in our memory that Spaemann highlighted. This online audience is simultaneously ever-present but elusive, especially through mobile devices. It remains at a physical remove, but our interactions with it can approximate the immediacy of face-to-face communication, in that reactions can be instantaneous and pointed directly at us. Response can also trickle in over time, from respondents that range from expected to unanticipated to unwanted. The audience’s resulting dispersal through space and time leads to a sporadic and unpredictable set of interactions, which can anchor habits of continual checking or an intensified susceptibility to push notifications (part of how platforms try to elicit compulsive engagement). The result is that we can’t help but be aware of ourselves through these platforms as continual performers, moment by moment.

To glance at your profile, to frame an image or message for posting, or to scroll through an algorithmically sorted feed is to see at least some aspect of yourself suspended in time

This audience elicits a different kind of performance from writing, “heightening consciousness” in a different way. Writing, in Ong’s view, generated an individuating and interiorizing experience of the self. But the perpetual, open-ended encounters through social media retrieve certain dynamics of oral societies, integrating us into what seems like a live audience but is in fact stripped of many of the vital cues we read to make sense of our situation and act accordingly. The rich array of handles supplied to communication when bodies share a physical space are lost, so interactions become marked by heightened volatility, uncertainty, and anxiety. If the self we become aware of when we write (or read) appears to us as a solitary reality encountered within, broadcast-oriented social media posits an immanent, exteriorized self contingent on continued exposure.

What kind of self derives from this condition? Imagine a wedding photographer who circulates, trying to capture candid images of spontaneous or unscripted moments. “Act naturally,” they might joke, before encouraging everyone to “pretend I’m not here,” ironically vocalizing the impossible possibility to diffuse some of the pressure of doing as they say. Now imagine that you are that photographer, but that it is also your wedding. And imagine also that the wedding never ends.

Acting “naturally” implies a measure of self-forgetfulness, but foregrounding the camera and the stakes of the images precludes that. It achieves the contrary, heightening self-awareness, leaving people trapped in a state of perpetual consciousness of performing, referencing it repeatedly in an effort to disavow or mitigate it. To borrow sociologist Erving Goffman’s terminology, broadcasting on social media amounts to a substantial expansion of what he called our “front stage,” where we are consciously and continually involved in the work of impression management. In his metaphor of social life as theater, Goffman presumed the existence of a backstage, where we can let down our guard, but the open-ended communication in time and space on social media expands our front stage, divorcing it from any particular place that we could choose to leave. The audience is always potentially there with us, always soliciting new material, prompting us to think of our lives in terms of material. Those who give the appearance of inviting an audience into the intimacy of the backstage realm, in fact, often seem the most adept at using social media, as if this were the fundamental skill it hones. But they have really mastered the art of transforming the backstage into another front stage.

The front stage thus begins to colonize the backstage. Provided you have a connected mobile device, you can always be involved in impression management, even if you find yourself alone. Indeed, we seem to crave the front-stage experience to the degree that we find it difficult to tolerate solitude.

It may seem that we’ve come a long way from “millennial burnout,” so let me try to make the connection more apparent by way of Hamlet, another person who had trouble getting things done. His “To be or not to be” soliloquy is, among other things, about “errand paralysis,” giving voice to the paralyzing power of his unrelenting self-consciousness:

Thus conscience does make cowards of us all,

And thus the native hue of resolution

Is sicklied o’er with the pale cast of thought,

And enterprises of great pitch and moment

With this regard their currents turn awry,

And lose the name of action.

Though we may not be contemplating literal revenge killings, our social media use still may have something in common with what Hamlet articulates in these lines. Our own unrelenting self-consciousness may similarly cause our “enterprises,” be they great or trivial, to “lose the name of action.” The self that experiences itself chiefly in front-stage mode — owning the conspicuous artificiality of its situation and trying to manage the impressions of how much impression management it’s doing — may discover that it is both exhausted and no longer sure of itself. Whatever assurance we might have about our motives, intentions, and purposes dissolves under the withering light of such unrelenting self-consciousness. Hence the paralysis of will.

We can understand backstage experience, then, as a respite not only from the gaze of an audience but also the gaze we must fix on ourselves to pull off our performances. By colonizing the comparatively unguarded and relaxed backstage, the front-stage social-media experience deprives the self of a space for renewal. “If you tell people how they can sublimate,” the psychologist Harry Stack Sullivan once quipped, “they can’t sublimate.” Likewise, if you perpetually involve people in the work of becoming themselves, they will never be themselves.

But this is, in fact, only part of the picture. If platforms deplete our willpower by making us hyper-self-conscious, they also are increasingly structured to make us experience the will as beside the point. Platforms are designed to make us less conscious of our decisions about how we spend time on them, attempting to automate decision-making with auto-play, notifications, and algorithmically optimized feeds to generate compulsive “engagement.” The algorithms that ostensibly reveal what your “true” or “authentic” self would choose for itself feed off the very exhaustion that the platforms generate, offering refuge from the burden of identity work in the automation of the will. Our noonday devil thus takes the form of the infinite scroll and the listlessness it induces. (It is suggestive that a popular tool for online time management is called Freedom.)

If platforms deplete our willpower by making us hyper-self-conscious, they also are increasingly structured to make us experience the will as beside the point

Social media platforms, then, heighten our consciousness of the performative aspects of our identity and simultaneously aim to diminish our consciousness of how we use them. These two seemingly opposed tendencies transform the platforms into powerful dissolvers of will, leaving us more susceptible to the algorithms and the marketing that powers their economic model, as well as structuring a particular form of social order. Rather than foster the display our individuality, they devolve into mechanisms of conditioning. The cumulative effect of the networks of surveillance, self-monitoring, operant conditioning, automation, routinization, and programmed predictability in which we are enmeshed is not enhanced freedom, individuality, spontaneity, thoughtfulness, or joy. Their effect is to stabilize us into routine and predictable patterns of behavior and consumption.

In The Origins of Totalitarianism, Hannah Arendt argues that “totalitarianism strives not toward despotic rule over men, but toward a system in which men are superfluous.” Superfluity, as Arendt uses the term, suggests some combination of thoughtless automatism, interchangeability, and expendability. A person is superfluous when they operate within a system in a completely predictable way and can, as a consequence, be easily replaced. Individuality is worse than meaningless in this context; it threatens the system and must be eradicated.

Arendt saw concentration camps as the prototypical fulfillment of the totalitarian threat to individuality: “The society of the dying established in the camps is the only form of society in which it is possible to dominate man entirely.” But the dark genius of our age has been to put a Huxleyan spin on that Orwellian threat, trading on the apparent expression of individuality rather than its suppression. Algorithmically driven social media platforms appear to encourage the expression of individuality, not only by inviting us to showcase our memories, tastes, preferences, aspirations, beliefs, and values but also by making those things appear to operate directly on the flow of material we will see. In reality, they aspire to be Skinner boxes. Spontaneous desire, serendipity, much of what Arendt classified as “natality” — the capacity to make a beginning at the heart of our individuality — all of it is invoked only to serve the purposes of achieving programmed predictability.

Perhaps it seems that Arendt’s theorizing about 20th century totalitarianism has little to do with the ephemeral and trivial nature of so much of what transpires on social media platforms. However, as Arendt warned, “totalitarian solutions may well survive the fall of totalitarian regimes in the form of strong temptations which will come up whenever it seems impossible to alleviate political, social, or economic misery in a manner worthy of man.” Or, we might add, when the temptation is the banal aim of maximizing profit by hijacking the all too human desire to appear before others and perhaps be affirmed in our distinctive particularity.

In a 1954 essay, “The Crisis in Education,” Arendt observed that “everything that lives, not vegetative life alone, emerges from darkness and, however strong its natural tendency to thrust itself into the light, it nevertheless needs the security of darkness to grow at all.” She has in mind the place of security that is necessary for a child’s healthy development, but the observation applies more widely. The self, at whatever stage of maturity, may need a place of darkness if it is to continue to grow. But in our current situation, the self is continuously bathed in the light of heightened self-consciousness. Along similar lines, one of Arendt’s first professors at the University of Berlin, Romano Guardini, wrote, “Life needs the protection of nonawareness.” “Our action is constantly interrupted by reflection on it,” he added. “Thus all our life bears the distinctive character of what is interrupted, broken. It does not have the great line that is sure of itself, the confident movement deriving from the self.”

The practice of performing our lives before a diffuse, semi-present, always available audience has brought a withering light to bear upon our inner lives while suffusing our public acts with doubt, half-heartedness, and hesitation. But that doesn’t mean we should be striving to return to some more authentic or unmediated self that might now seem as though it had been available to us in the age before social media. Rather the point is that the experience of the self always emerges in relation to the media used to express it. These media are neither neutral nor interchangeable in how they give particular form to the self and circulate it. The question we should ask, then, is whether the distinctive experience of the self implicit in how we now communicate is conducive to our flourishing and to the cultivation of a more just society. We have reason to be skeptical on both counts.