It sounds familiar, but in an unsettling way. The reverb and distortion, the minor key guitars, the pounding drums, the singer with no regard for his vocal cords. There is a vague sense that the creators don’t want to be there, but would rather be there than anywhere else. The lyrics contain one or two passable metaphors, but are too vague to make an emotional impact. The riff could have been lifted from any number of songs, and yet it doesn’t quite sound like a song at all.

In recent years there has been a flurry of unreleased Nirvana demos and recordings made public. If “Drowned In the Sun” were one of them, then I’m afraid we loyal and melancholy fans would be left cold. Luckily, it isn’t the new Nirvana song. It was created by Magenta, Google’s Artificial Intelligence program, which was fed MIDI files of “20 or 30” Nirvana songs to analyze and reconfigure. The single’s chord progressions and aggressive rhythms were composed and performed by a computer; the only “human” element is vocalist Eric Hogan, singer for Atlanta-based Nirvana tribute act Nevermind, performing the words and tune Magenta wrote.

The logic of an undertaking like Lost Tapes of the 27 Club is, in its own way, intensely depressing

Released on April 5th, on the 27th anniversary of Kurt Cobain’s suicide, “Drowned” is the latest entry in the Lost Tapes of the 27 Club, an ongoing series by Toronto-based nonprofit Over the Bridge, which is dedicated to raising awareness of mental health issues in the music and recording communities. These issues “[haven’t] just been ignored,” the organization explains on its website. “[They’ve] been romanticized, by things like the 27 Club — a group of musicians whose lives were all lost at just 27 years old. To draw attention to this issue, we used AI to imagine what these artists might have created, were they still with us.” To date they have released other songs in the style of Jimi Hendrix, Amy Winehouse, and the Doors.

The languid romance of ennui and alienation have always been the bane of the artist’s existence and their most uncomfortably alluring characteristic. Not only is this normalized in the music industry, it is also frequently used as a marketing gimmick. There is no arguing with the assertion that musicians struggling with mental illness or substance abuse are in dire need of resources. If Lost Tapes of the 27 Club has, as Over the Bridge claims, moved musicians to reach out to the organization in search of those resources, then that is a net positive. Still, the logic of an undertaking like this is, in its own way, intensely depressing.

There is an inevitable anxiety among musicians when AI generated songs are released: rhetoric about the death of “real” music, the removal of the artists from the project of composition and performance. But technology and musicianship have always had a far more subtle and dynamic relationship than this hue and cry reflects — the need for a flesh-and-bone vocalist reveals as much, even if he is performing something AI-generated. No, the problem with “Drowned in the Sun” isn’t so much the specter of replacing human creativity, and human potential writ large, as much as constraining it.

The presumption behind “Drowned in the Sun” is that, had Kurt Cobain not taken his own life in 1994, he would have been writing and recording songs just like this. There is no denying the popularity of the sound that Cobain and Nirvana produced. Nor was it just thanks to savvy marketing. Record executives were bowled over by how far the music of Nevermind reached in 1991. Perhaps they should not have been: Though the dominant cultural narrative was one of post-Cold War triumphalism, most young people felt cut adrift. “Cobain seemed to give wearied voice to the despondency of the generation that had come after history,” Mark Fisher wrote, “whose every move was anticipated, tracked, bought and sold before it had even happened.”

An artist’s evolution is not the kind of thing that can be quantified, broken down into tropes — but that is what the music industry does, and also what Over the Bridge assumes

Of course, nothing sells like rebellion, and that bitter irony was never lost on Cobain. Whether he ever thought he would be able to cut the gordian knot between commerce and revolt is unclear, but it is clear that the connection took a toll on his mental health. By the time of his death, Cobain had already made buckets of cash for the music industry. The pressures of commodification, to keep creating same as he had over and over for a fanbase that is always static in the eyes of a major record label, would have been immense. That he already felt this pressure, that it contributed to the depression and despair he had always struggled with and that finally overtook him, is not speculation. He wrote about it in his suicide note.

“Cobain knew that he was just another piece of spectacle,” Fisher continues, “that nothing runs better on MTV than a protest against MTV; knew that his every move was a cliché scripted in advance, knew that even realizing it is a cliche.” An artist’s evolution is not the kind of thing that can be quantified, broken down into recognizable elements and tropes — but that is just what the music industry does. It is also, best intentions aside, what Over the Bridge and “Drowned in the Sun” assume.

Ultimately, we have no clue what kind of songs a much-revered musician like Cobain would be composing were he alive today. Though Nirvana had only three studio albums under their belt, it is well-known that Cobain was a curious artist and songwriter, uncomfortable with being pigeonholed. It is not outlandish to picture his future music going well beyond the sandbox corner of “grunge,” “the Seattle sound” or other marketing copy buzzwords. Our internal lives and how we relay them through art are subject to all manner of influences, including our mental health, and all the incalculable variables that make human life irreducible to code.

Generation X is not the last to have their desires manufactured and corralled in the same breath. The mechanisms by which our moves are anticipated and sold back to us are stronger than ever, aided by algorithms that atomize us and narrow the scope of human agency. The same futurelessness and commercial fetter on imagination that Fisher described in Cobain is deeply entrenched in our culture. It would be a mistake to miss the connection here, between this blunting of human creativity and the rise of anxiety, depression, and overall despair among young people, musicians included.

The mechanisms by which our moves are anticipated and sold back to us are stronger than ever, aided by algorithms that atomize us and narrow the scope of human agency

Google’s Magenta program is of a piece with other technologies that shape reality for both artists and fans. By now it is well-known that services like Spotify, reliant on algorithms that identify certain sounds, rhythms, and patterns in people’s listening habits, assert their own view on what we “should” be hearing. Artists have already felt pressure to tailor their songs to make it into one of Spotify’s coveted playlists, and with their average pay at less than half a penny per stream, who can blame them? Both Magenta and Spotify proceed from the notion of artist — and listener — as a passive participant rather than an active one. As these roles are delimited, so is our sense of time and continuity. If art, as Maynard Solomon puts it, “points toward the future by reference to the past and by liberation of the latent tendencies of the present,” then the immortalization of rock stars — the temporal freezing of their art — short-circuits this dialectic. We hear the sounds of 27 years ago copied and recapitulated today.

One wonders if “Drowned in the Sun,” and the Lost Tapes project itself, doesn’t just address the problem but also epitomize it. The idea that a person’s expressive potential could be quantified, programmed, and reproduced by artificial intelligence reinforces the sense of futility characteristic of neoliberal capitalism, the same futility Cobain grappled with nearly 30 years ago. Alleviating the crisis in mental health can’t be done by reconfiguring the past. It requires resources and institutions that provide us with the ability to explore the contours between present and future, which amplify our control over our own creativity rather than diverting it into the same feedback loop of terminal nostalgia.

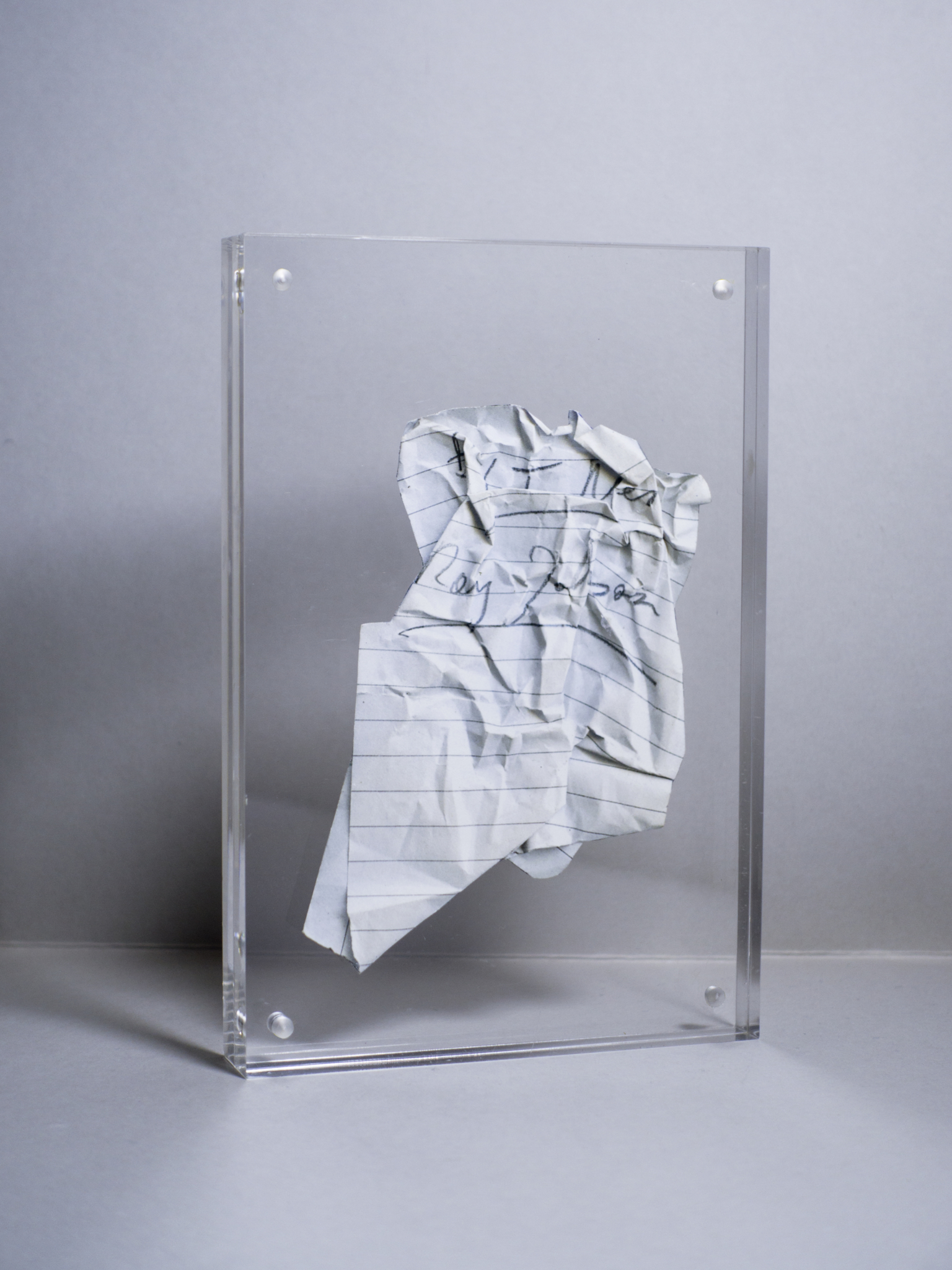

Not long before “Drowned In the Sun” was released, digital artist D.S. Bradford unveiled the latest in his Augmented Reality Music Icon Mural series. Located in Kurt Cobain’s hometown of Aberdeen, Washington, on the south bank of the Wishkah River, just east of the Young Street Bridge, the mural is viewable only through a smartphone or tablet, “accessed by the click of the button.” It shows Cobain’s face floating several meters above the water’s surface, the words “all is all is all we are” under his chin, smudged text and ripped fabric belying the digital intricacy used to create the image.

It isn’t difficult to picture someone standing on this bank, gazing at the mural through their device as it takes up space without taking space, hovering above interaction and effect. Perhaps their device is also suggesting which Nirvana song they would like to hear next.

If they are old enough, they might remember the moment when Nirvana’s sound felt like freedom from the interminable false optimism of the early ’90s. It is a comforting memory, but still a memory, wrapping itself full spectrum around the moment’s structure of feeling. The question, unasked and unanswered, is where that freedom might be found today.