In the United States in the year 2020, many people begin their days with an activity known as “doom scrolling,” their gazes fixed on a stream of images and text created by other social media users and beamed to their smartphones in real time. Concerned psychologists suggest that this behavior is unhealthy; it foments anxiety, stress, and depression, which reduce our productivity. Such chiding is completely pointless in that the doom scrolling behavior has been carefully engineered by other psychologists as a source of boundless profit for the platforms that harvest our data while we interact with the stream. In the language of cyberpunk — once edgy, then ironic, now simply a grinding part of daily experience — we’re “plugged in” to a larger consciousness, an atmosphere of information from which no one can seal themselves off.

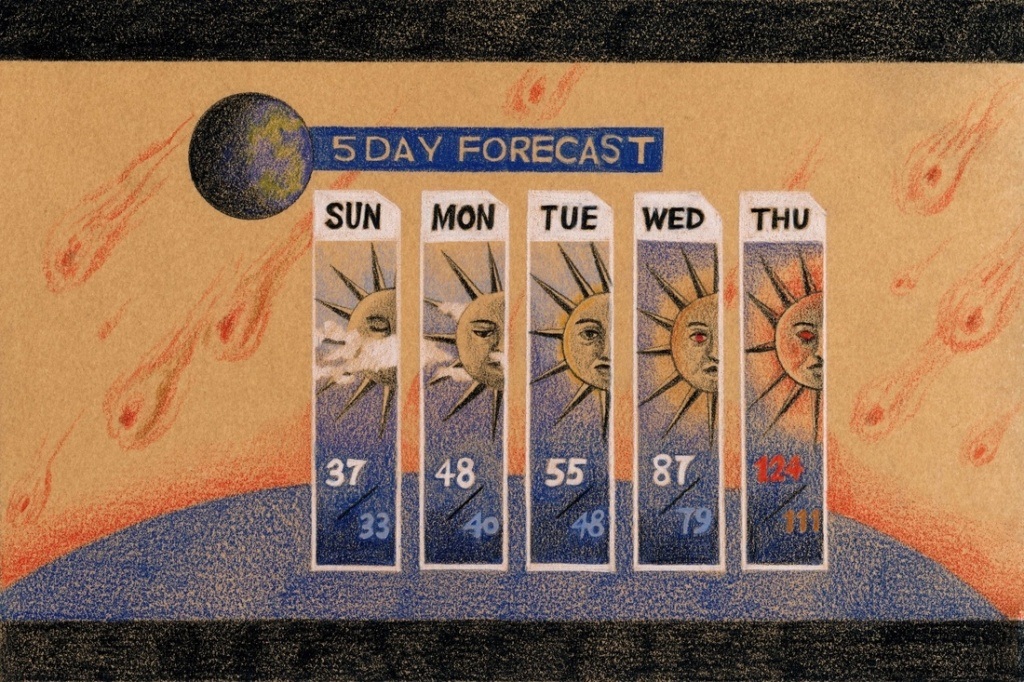

If a person, following the psychologists’ self-help advice, were to put their phone down and walk outside to greet the morning — well, that’s not advisable either. Doom lies not in the scroll; it’s carried on the wind. During seasons of risk, increasingly all seasons, one needs to know the level of various deadly things in the air. I see, in a stream, photos of my friend’s car covered in ash, an animated heat map of plague levels in each state, clouds of chemical weapons engulfing protests. Choosing to put down your phone changes none of this. An opinion poll indicates that while 52 percent of registered voters are concerned about violence caused by protests against police brutality, only 43 percent are concerned about police brutality. We breathe the same air, until we don’t.

Weather is a ready-to-hand metaphor for currents of thought: It permeates, yet the experience of it is highly stratified. To represent it, researchers make maps

Weather is a ready-to-hand metaphor for the abstract yet visceral currents of thought in which people are immersed, the feeling of being in social, political, and cultural relation with millions of others. It permeates experience, yet the experience of it is highly stratified and segmented. To represent it, researchers make maps filled with colors and symbols that stand for the distribution of sentiments across geographic space. The sense of public opinion or national feeling as an atmospheric condition, amenable to the same tools of representation and modeling used in meteorology, has a curious history. Never formally articulated, it flits across the 20th-century social and human sciences as a set of expectations about how to measure and control the national mind. The association might seem purely rhetorical — psychologists have dreamed of predicting behavior as meteorologists predict the weather — but it has certain methodological and conceptual continuities.

These continuities can foreground the widespread feeling that our mental weather has become ever-more intense. We rely on the instruments that observe us to understand ourselves. Those instruments, in the formulation of Donald McKenzie, are engines, not cameras (although they have built-in cameras too). They seamlessly exploit and channel political behavior, contributing to a kind of climate change not unlike that which is the legacy of the internal combustion engine, unleashing feedback effects, heightening turbulence. Yet, for a period of time in the 20th century, science claimed to be edging towards mastery over both the meteorological and psychological weather. The idea that data and innovation could optimize those forces failed to grasp the material, political conditions from which they arise.

In 1873, a New York doctor named Thomas Davison Crothers wrote about an “atmosphere of mind” which he believed was influencing the health of his patients. Our feelings “do not depend alone upon the senses of hearing or seeing,” he argued. Rather, each person is embedded in the vast and invisible mental atmosphere that conveys feeling the same way an air mass sweeps across the land. For sensitive or very ill patients, agitations of the mental atmosphere could “destroy life.” Crothers described a local lawyer who was “prostrated with overwork” and sent to rest in a country retreat. The lawyer made a good recovery until one day he “became violently agitated,” overwhelmed by a sudden excitement that left him feeble and exhausted for two weeks. He later found out that, at the very moment of his agitation, he had been nominated to run for Congress during a political convention in the city. The lawyer “firmly believes,” concluded Crothers, that the uproarious feelings of the convention “influenced his weakened nervous system…although he was many miles away, and not aware of its meeting.” More anecdotes of mobs, riots, and political uproar flowed from Crothers’ pen, forming a picture of a country united in agitation from which none could escape.

Crothers was very invested in this idea of the mental atmosphere, which went far beyond the metaphor of a national mood or public sentiment. Like many men of science in the 19th century, he was hunting the white whale of mental force. There had to be some physical explanation for the influence of one mind on another, just as magnetism explained the movement of a compass needle. Indeed, “animal magnetism,” deployed by professional mesmerists, had been a popular medical treatment a few decades earlier. Crothers was more interested in how mental force acted in the wild. How did a mob know to rush to the street in anger? Why couldn’t his patients escape the clutches of party politics? Such phenomena, operating on the vast scale of the American landscape, were both frightening and galvanizing.

This atmospherics of feeling coincided with advancing scientific study of the earth’s literal, gaseous atmosphere. In the 1850s, the Smithsonian Institution began collecting simultaneous weather observations from around the country, via newly-laid telegraph wires, and plotting them on a large wall map, publicly displayed. This form of data organization, known as a synoptic chart, made the motions of air masses visible for the first time. The Smithsonian provided a God’s-eye view of atmospheric currents of which the earth-bound individual only saw a small part. Harvard’s William James, who is remembered as the founder of American psychology but also established a society for the study of psychic phenomena such as clairvoyance and telepathy, embraced the analogy between weather and mental experience. Both weather and experience were “discontinuous and chaotic… But the Washington weather-bureau intellectualizes this disorder” with its synoptic charts, fixing every data point “to its place and moment in a continental cyclone.” James hoped to do the same for psychic phenomena with his American Society for Psychical Research, which requested reports of premonitions and intuitions of the variety that Crothers collected.

The weather had a line in the federal budget because of its economic and military implications: it held agriculture, shipping, and colonial expansion at its mercy. Predicting the weather was part of an imperial project that created the “self-evident” shared identity and interests of a nation. If unruly weather could undermine these interests, the mental atmosphere posed a similar hazard. To some extent, investigators who pored over psychic anecdotes saw them also as affirming a shared national identity. At the same time, comfortable, middle-class, white investigators like Crothers feared even metaphysical contact with the great mass of people unlike themselves, and stoked anxiety about mental contamination. The notion of dangerous feelings spreading through some elemental psychic force mystified the political agency of “others” through the assumption that they acted impulsively and automatically.

There had to be some physical explanation for the influence of one mind on another: How did a mob know to rush to the street in anger? Why couldn’t Crothers’ patients escape the clutches of party politics?

A growing class of experts, taking this synoptic view of human behavior, addressed themselves to managing mental disturbances that threatened the order of capitalist democracy. William McDougall, who led the American Society for Psychical Research briefly in the 1920s, is better remembered as a founder of social psychology, a field preoccupied with such phenomena as the contagion of the crowd and later the “mass hysterias” of fascism and communism. Because he believed certain types of people more susceptible to” the coarser emotions and less refined sentiments,” McDougall saw eugenic population control as the only way to render America’s mental atmosphere” safe for democracy.” Through draconian immigration restrictions, intelligence testing, and eugenic sterilization of people deemed “unfit,” the United States attempted to shape the bodies and minds within its borders. Social scientists were increasingly engaged in such matters of national interest, treating the “mass man” as a kind of meteorological phenomenon to observe, track, and — they imagined — predict and control.

Though the human sciences looked to the Weather Bureau’s state-of-the-art observation system as a model, weather prediction was very limited in the early decades of the 20th century. Forecasts were empirical, based on patterns and past experience. As of 1922, expert forecasters could predict the weather up to two days in advance with reasonable accuracy. Government and industry longed for knowledge of future conditions beyond the two-day horizon, and this interest only grew during World War I, when strategy for land, sea, and air offensives hinged on the weather. Lewis Fry Richardson, a promising young superintendent for the British Meteorological Office, had left his post to serve in an ambulance corps at the front. While lodged in the trenches he began a novel attempt at numerical forecasting, using mathematical analysis of past weather data to predict the future. His forecast was incorrect, and the computations took him six weeks, but Richardson believed that his method was sound — if only he had better data and more computing power.

Mathematical forecasting would eventually transform meteorology, but Richardson abandoned the field in 1920. As a Quaker, he refused to work for the Meteorological Office when it was placed under the auspices of the British military. Perhaps his “intense objection to killing people” helped form the idea of applying his forecasting method to the psychology of human conflicts. In the years that followed, he created a system of equations to model the likelihood of war — to predict and, he imagined, prevent “disturbances of the psychic atmosphere” among nations. Richardson didn’t imagine, as Crothers had, a literal mental force flowing from mind to mind. His argument was simply that the complex dynamics of weather and human relations are amenable to the same analytic tools.

In the 1950s, Richardson’s dream of weather computation became a reality under the initiative of Hungarian mathematician John von Neumann. Von Neumann had played a pivotal role in the Manhattan project, contributing to the design of the atomic bomb and helping to choose its targets — he described himself as “a good deal more militaristic than most.” He seized upon weather forecasting as the perfect task to prove the strategic usefulness of the first electronic computer, the ENIAC. What had taken Richardson six weeks to get wrong took the electronic computer a day to get right, and would soon take split-seconds. Von Neumann was bullish about using such powerful atmospheric modeling to exert human control over the weather. However, aside from localized cloud seeding, weather manipulation has never proved technically or ethically feasible on a large scale — even as a last-ditch effort to halt climate change, it poses dire risks that the best models may fail to calculate.

The atmospherics of feeling operating on the vast American landscape coincided with advancing scientific study of the earth’s gaseous atmosphere

Von Neumann, like Richardson, confidently applied his predictive prowess to both weather and the human mind. In 1944 he published, with political economist Oskar Morgenstern, the influential treatise Theory of Games and Economic Behavior. Whereas Richardson envisioned mass violence as an emergent phenomenon tipped off by many smaller “whorls” of stress and sentiment, von Neumann and Morgenstern reduced conflict to a set of rational decisions made by players to optimize competitive outcomes. Their scenarios were supposed to model the probable moves of U.S. and Soviet leaders in the nuclear stalemate. Unlike the many-layered complexity of weather modeling, the scenarios presented in Theory of Games took place in a realm of formal abstraction where the players alone controlled their fates.

Over the course of the Cold War, the messy mental atmosphere crept back in to models of human behavior, whether in panics over mass-media brainwashing or in psychological studies of bias, irrationality, and conformity. Richardson had anticipated such refutations of game theory. If politics is a game of chess, he wrote, “it is somewhat as if the chessmen were connected by horizontal springs to heavy weights beyond the chessboard.” The image of chess pieces weighted by hidden springs of history, culture, and psychology is surely closer to life, yet even this optimistically supposes that each tendril of influence could be isolated and quantified. Psychology has always dealt in subjective metrics, from eugenic fitness and criminality to intelligence and neuroticism, that measure shifting, socially-assigned qualities as though they were facts of nature. The thermometer and barometer, though not ahistorical themselves, present a much more constant picture of material reality.

Sometimes simplifications work — mathematical weather forecasting showed that a good-enough model can achieve impressive predictive power. The problem with applying this method to people is that they don’t merely generate data; they absorb and are changed by it in much the way Crothers imagined his patients infiltrated by the mental atmosphere. As historian Sarah Igo writes, the categories that 20th-century researchers constructed to assess everything from politics to sexuality were quickly taken up by the public as objective self-descriptions. Igo notes that research subjects had a strong desire to know where they stood, as points in a statistical cloud, as “normal” or “abnormal” in relation to polls and surveys.

The opinion research of the later 20th century gave us an aerial view of the country as made up of red and blue states, “security moms” and the aggrieved “white working class.” Consumer confidence stood in for well-being. Analysts gathered around these synoptic maps of feelings and attitudes to diagnose and make increasingly daring predictions. Yet they missed what most of us would consider, so far, the storms of the century: the financial collapse of 2008; the election of Donald Trump in 2016; nationwide uprisings against racism and police violence; the growth of right-wing reaction. To be in the midst of these storms is to feel a turbulence breaking out that has built for a long time. The sense that people can’t take any more pain is difficult to state in numbers. It calls into question central objectives of the social and human sciences as they’re operationalized in the great 21st century data-rush — the assumption that the discrete units of feeling they can easily produce and track are the ones that matter. Treating human sentiments like the weather, a natural phenomenon to be studied and exploited, means not engaging with social needs and political demands.

Today, Americans are just as heavily-monitored as the weather — the same smartphones that capture our taps and swipes can also report local temperature and pressure. From the user’s hand, these two data streams flow in parallel across physical infrastructures of satellites and server farms, through algorithmic processes that discern their significance and value in real time. The goal, in both cases, is forecasting. The corporate pitch for harvesting weather data from your phone is that you’ll need hyper-accurate local forecasts to survive in a catastrophe-ridden future. The amazing computational power that allows us to model climate change has not helped to avert it.

In the case of the mental atmosphere, the expansive Cold War vision of modeling, prediction, and control has become similarly narrowed to a pragmatic focus on short-term profitability. Psychologists plugged in to tech companies’ endless streams of data, promising that their models would effectively target users for advertising and, more importantly, influence user behavior. By sorting people into categories, and engineering how those people encountered information within social media relationships, they modified the political climate in ways that no one bothered to model. In the proprietary spheres of platform capitalism — micro-climates with no accountability for cumulative effects — these are not the questions one gets paid to ask. Such manipulations of the physical atmosphere were banned by international treaty in 1977, precisely for fear of cascading global consequences that defied our predictive abilities.

Treating human sentiments like the weather, a natural phenomenon to be studied and exploited, means not engaging with social needs and political demands

The doom scroll is a product and process of this phenomenon, a synoptic chart used to locate ourselves amid the objectively miserable conditions of the present moment. If a person goes outside to greet the morning, without first checking the body count, how do they know what kind of day it is? Others betray nothing in their actions, walking down the street, waiting for the bus. This is uncanny, many remark — this sinister persistence of normalcy. How much suffering can be hidden behind closed doors? How much can people take? The logical expectation that people can’t take any more has led conservative talk-show hosts to posit that the nation’s cities are aflame in active rebellion. If you have a certain kind of news feed, it could look that way, and you could neither know nor care that the greatest violence occurs under so-called normal conditions.

As in the 19th century, dangerous feelings originate “somewhere else” — never granted an independent reality, they only register when they penetrate the sphere of normative white sensibility. Crothers advised that sensitive patients be removed as far as possible from cities, yet his own examples troublingly showed that distance was no obstacle to the currents of the mental atmosphere. Today, conservatives declare that the suburbs are under siege. It’s not that de-facto racial and economic segregation has been breached in any meaningful way; rather, the vector of assault is the digital devices that render people permeable to a stream of words and images optimized for maximum emotional engagement. Certainly, people in the past also responded to ideas with violent feelings, thus Crothers’ sense that certain feelings are simply “in the air,” taking hold regardless of specific vectors. Yet many people understand social media as information rather than an intervention in their own affects calculated to produce more feelings, more attention, and more data. Platforms may claim that their algorithms have no ideology, but the arrangement by which they profit from anger and fear is an ideological one.

One specific weather instrument was especially treasured by 19th century meteorologists: the barometer. Unlike the thermometer, which measured current weather, the barometer had a rudimentary ability to detect what was coming before a human observer could perceive any change: “a storm a thousand miles off makes [the barometer] tremble.” Crothers envisioned people as barometers with varying degrees of sensitivity to the mental atmosphere of social and political life. Most Americans today carry a digital barometer in their pockets which both monitors and modifies; the person equipped with this technology is an instrument honed by its own observability, whether in suburban retrenchment or in the tumult of an uprising.

There may truly be a mental atmosphere in Crothers’ sense, a community of feeling whose agitation we perceive in moments of stress and upheaval. Our goal can’t be to unplug from or manage it, when it emanates from real conditions that remain unchanged. To be clear, what divides Americans is not new technology but the oldest of commitments to white supremacy and wealth extraction. Breaking their hold would by definition cut against the prevailing winds — it will always require, and create, dangerous feelings. Yet the scientific dream of molding those feelings, and the reality of manipulating them for profit, have changed the dynamics of our atmosphere in unforeseen ways. Even as we scrutinize maps, aggregations, and feeds for some sense of what to expect, what to think, what to do — and even as these channels help to organize necessary action — we need to ask why we’ve allowed our permeability to be exploited, when we see and feel so intensely that the damage cannot be contained.