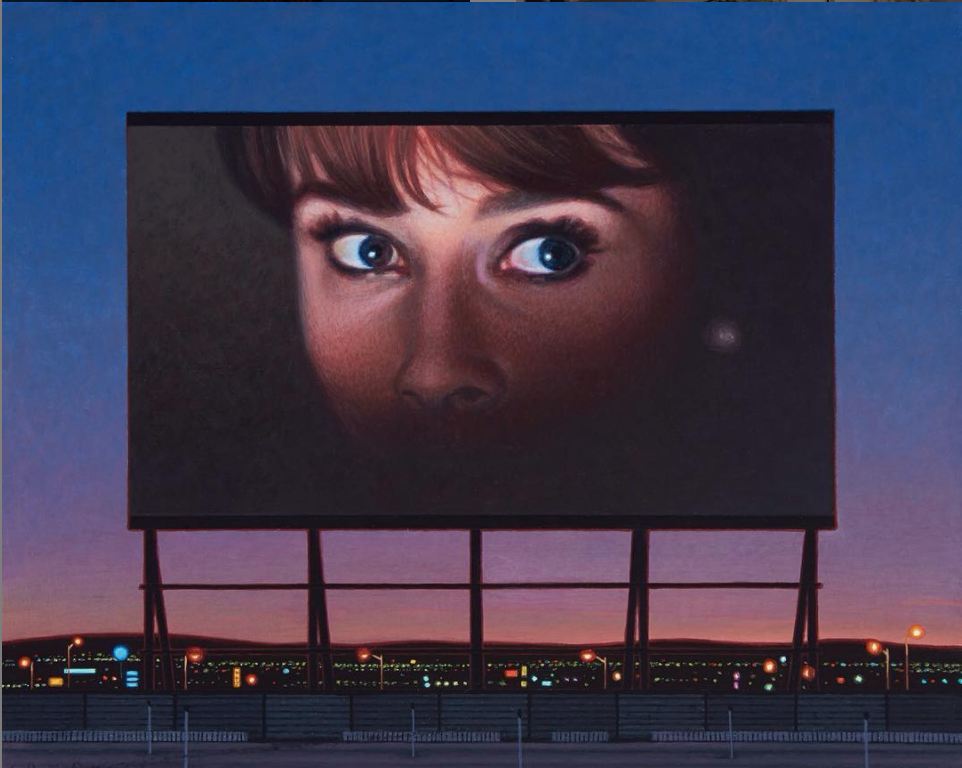

The drive-in looms in our collective memory, irrespective of first-hand experience. They evoke hot dogs smothered in fluorescent mustard, popcorn disappearing down car seat crevices and the rattle of iced drinks forced into cup holders. They draw on the feeling of sweaty legs on leather seats, of small hands reaching round headrests, trainers on the hot tarmac and the gentle hum of the AC, bleeding into the film’s audio. Zooming out, the image becomes increasingly static under the night sky. In uniform lines, the cars seem abandoned. Above the ether of flood lights and neon signs, the landscape is framed within the grey ambient glow of the screen appearing like an overexposed negative. The sentimentality that lacquers the drive-in experience legitimizes spending, making audiences feel as though they are paying for a memory rather than a consumer experience, all the while their environmentally damaging aspects are rendered campy with the gimmicky nickname, “ozoners.”

Far from a golden-age pastime, the drive-in is a recycled solution to the question of collective entertainment at a time of separation

Their reliance on land and cars feels distinctly American, but drive-ins are opening up all around the world. They have retained their kitsch aesthetic, selling audiences not just a ticket to a show but an idealized conception of America’s past. This image is confused and inconsistent: we see drive-ins as totemic of 1950s family values, but this association is itself a product of nostalgia, made manifest in ’70s films and shows like Grease and Happy Days. Still, at a time where the future feels indeterminate, this is enormously appealing and lucrative, allowing audience to slip into a cozy fiction, while easing them back into the slip-streams of consumption. The founder of Luna cinema, the UK’s largest outdoor movie business, put it this way: “People need to rebuild their confidence before they’ll step back into a theatre or cinema — and drive-ins are the perfect socially distanced event.” He qualified that they “will be the route back to all entertainment.” This gestures towards broader issues of capitalist recovery; how do you get people to spend when they feel unsafe, unable or reluctant to do so? This question lingers in the periphery of our “new normal,” where the past is increasingly invoked as an instrument of growth.

The “new normal” draws out the tension between capitalism’s emphasis on progress and its invariable “busts” of recession. The term itself appears a paradox — “new” insinuating a disruption of the past, with “normal” implying its continuation. Politicians and journalists have used it to encourage our acclimatization to the unique conditions produced by the pandemic, such as drive-in medical appointments, sports without crowds, and accessorized face-masks. The notion of the “new normal” is nothing new: Coined by the International Monetary Fund in response to the 2008 economic crisis, the term was used to describe the continuation of neoliberal policies and business practices in the face of recession, resulting in “muted growth” and “stubbornly high unemployment” — the same realities of today. The drive-in is an effective instrument of the new normal, evoking the post-war optimism of the 1950s, reminding us of a time when the future felt inviting. In this sense, they enable us to look forward, but only through the lens of what has come before. Led into an endless cycle of short-term solutions, our problems only mount with time, while the drive-in placates our anxieties and desire for meaningful change.

Narratives of the drive-in’s early development are usually prefaced with a quaint anecdote. Their inventor — Richard Hollingshead Jr., a general sales manager at an auto parts company — wanted to go to the cinema with his mother, but she struggled to sit comfortably within their seats, so he brought the film to her, placing a screen in front of her car. Others describe how Hollingshead Jr. saw a business opportunity within the Great Depression. At a time when people weren’t spending frivolously, entertainment felt like a desirable but unattainable distraction. In constructing the first drive-in alongside a gas station and restaurant, he tied the luxury of cinema to commodities that people could not give up in times of economic hardship. Placed within this context of requirement, the drive-in was somewhere people had to go and by proxy, films were re-contextualized as an excusable expense. Now associated with the picket-fence privilege of suburbia, their image has been cultivated and warped by films over time. Their original appeal was in their accessibility at times of deprivation, which in many ways still holds true. Catering to a working-class audience, they were the location of cheap dates — nicknamed “passion pits” — and almost exclusively screened B movies.

Led into an endless cycle of short-term solutions, our problems only mount with time

At the height of their popularity in the 1950s, 4,000 drive-in cinemas functioned across the U.S., servicing a post-war weary America. Although it is often overlooked, this was also a time of pandemic. Like Covid-19, polio necessitated quarantines, imposed ubiquitously on towns and households, and resulting in the closure of public spaces, venues, and schools. Drive-ins marketed themselves as “flu and polio protected,” alleviating the concerns of parents, who feared exposing their children to local epidemics, and found solace in the privacy of their own cars. Distanced, in the fresh air, drive-ins appeared to offer a sense of togetherness at a time of separation. Far from a golden-age pastime, the drive-in is a recycled solution to the question of collective entertainment in “times of uncertainty.”

Part of the novelty of the drive-in experience is looking back at how far we have come. We are meant to feel endeared to the crackle of the iron speakers, the glare of the light pollution and the flood of windscreens punctuating our view. Upon closer inspection, such a reflection might achieve the opposite effect: drive-ins expose our capitalist societies’ inability to adapt, and thereby evidence the fallacy of purported progress itself.

When the past is repackaged as new, it clutters the potential for a genuine future. Mark Fisher characterizes this as the “slow cancellation of the future,” where the past does not recoil from the “new” in “fear and incomprehension,” but would rather “be startled by the sheer persistence of its recognizable forms.” This is to say that the cultural changes we have undergone in the past 40 years are not drastic but surprisingly limited. The drive-in — like vintage phone filters, ’80s reboots and vinyl collections — is one instance of this broad temporal staticity. Fisher claims that this myopia is a consequence of neoliberalism’s short-termism, where quick fixes are consistently prioritized over structural change. This is executed through a program of austerity measures that systematically deny people of the means to create the future, leaving no option but to rework the past. The “new normal” encapsulates this tendency: years of public health cuts have deprived thousands of their futures, leaving many others stranded in impossibly difficult lockdown situations. The drive-in is once again resurrected as consolation, an empty symbol of the comfortable and familiar.

We find ourselves stuck in a cycle where the current worst-case scenario is resolved by a new one

The irony is that the pandemic has been lauded as a moment of technological innovation. Politicians have hailed the potential for automation and video communication to deliver a “no-touch” future, making physical workplaces, schools and other public institutions redundant. Within this image, infectious human hands are sealed off, the sanitary glove replaced with a more dexterous cursor, as we remotely accelerate towards a more efficient and dynamic horizon. In reality, these undesirable technologies represent nothing new, offering an insufficient band-aid in lieu of effective government preparation, all the while building on a privatized vision of public services. They are in many ways on a continuum with the drive-in: Brought in to make-do.

In their heyday, drive-ins catered to a desire for outdoor entertainment, but also for greater privacy. The drive-in invited audiences to kick off their shoes, have a cold drink and sink into their seats, making the car’s interior a personal living room. Upon stepping out of their cars, as though opening their front doors, people were engulfed by the bustle of crowds, clustering around concession stands, queuing up for rounds of mini-golf or lurking around arcade games. From the beginning, drive-ins exploited the trend towards private entertainment. By the 1970s they were made redundant by this very industry. Ultimately, the decline of the drive-in can be attributed to their failure to effectively bridge this gulf between private and public, leading to their respective replacement with multiplexes and televisions. As TV became more commonplace and affordable, desires for more public viewings were met by the emergence of malls, which offered smaller, cheaper and easily accessible cinemas. The drive-in’s liminality is the cause of its demise, as it increasingly failed to meet peoples’ desires for distinct private and public realms.

New social distance-enabling tech attempts to straddle this divide, but is fundamentally laden with the same problems, neither bringing us the connectedness we desire nor the sense of privacy. As the car became a living room at the drive-in, government sanctions demand our homes become hospitals and schools. Our homes have felt smaller not only because many of us are constantly in them, but also because they have been co-opted and repurposed. Drive-ins have returned to alleviate our feelings of isolation and distance, but problems of atomization and alienation far predate our current situation and run much deeper than a lack of collective pasttimes. At best, the drive-in conjures a fantasy of authentic togetherness.

The cornerstone of the drive-in’s charm is nostalgia. But part of the drive-in’s appeal is that it evokes an image of a time when we didn’t have to rely on nostalgia for escapism. Now that the future is obscure, and imaginable only in increments, we find ourselves stuck in a cycle where the current worst-case scenario is resolved by a new one.

Though its contemporary association is more sentimental and tender, “nostalgia” was originally used to describe feelings of pain in recollection; nostros meaning “return” and algos meaning “pain.” Akin to lockdown, it particularly connoted the moral pain associated with forced separation from loved ones and familiar environments. The drive-in appears as a synthesis of both meanings of the word — a token of an idealized past, and a reminder of our inability to move forward.