Despite bans by Reddit, PornHub, and other sites, a simple Google search will turn up numerous porn clips known as deepfakes, which use algorithms to superimpose the face of a celebrity over the face of the original performer and reproduce their facial expressions. (The term stems from the Reddit user name of a programmer who was instrumental in developing this process, interviewed here by Motherboard.) The software for deepfakes has been bundled into an easy-to-use package, allowing anyone with a reasonably powerful computer (even journalists) to create them. As a result, new deepfakes emerge daily. Though they all employ similar algorithmic tools, the results vary in quality. Some integrate the new faces almost seamlessly; in others, the new face floats haphazardly over the host body. The character of the final product is determined by the source material input into the algorithms — celebrities are targeted not only because they are popular objects of sexual fantasy but because their vast media presence provides hundreds of hours of footage with which to train the algorithms.

The emergence of deepfakes has had some commentators waxing ontological: “If anything can be real, nothing is real,” claimed a source interviewed by the Daily Mail. But deepfakes hardly constitute a paradigm shift in our trust relationship with images. For decades now, Photoshop has made it possible to convincingly falsify images, and faked pornographic still photos of celebrities have been ubiquitous since the time of Napster. It was inevitable this practice would eventually translate to video.

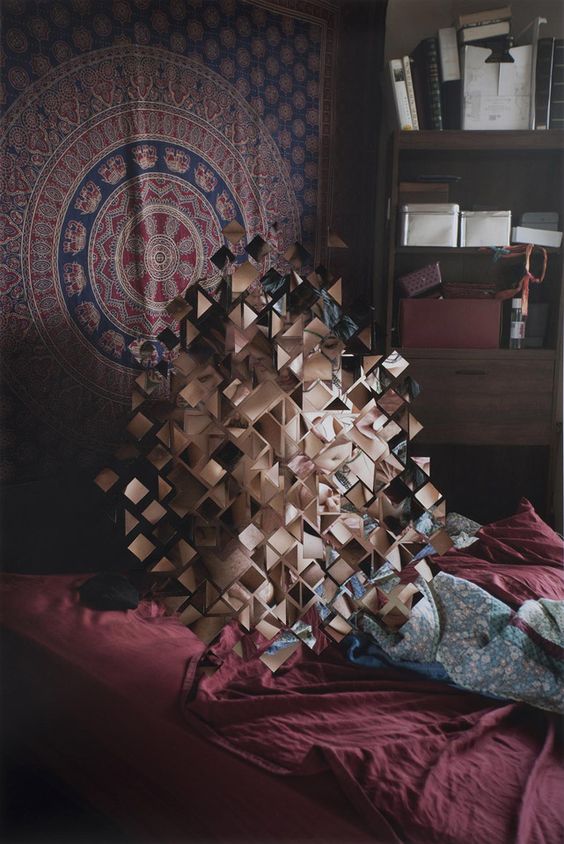

Too often, intimate digital images of the body are treated as if only information were being made vulnerable rather than an integral aspect of one’s person

Other writers are concerned at the possibility that fake videos will soon spread into politics. Deepfakes already have a distinctly alt-rightish cast, thriving in the same forums and often targeting women for their political views. For example, feminist media critic and Gamergate target Anita Sarkeesian’s face was superimposed on a masturbation video that remained on PornHub for at least a month despite that site’s supposed deepfakes ban. Michelle Obama has also been targeted, with forum commenters suggesting future Obama deepfakes use a male-bodied host to reinforce the right-wing conspiracy theory that she is a trans woman who was born “Michael.”

From a social justice perspective, deepfakes have been condemned as humiliating and violating the consent of the celebrities they purport to feature. As some commentators have already demanded, it is appropriate and necessary to frame deepfakes as a form of sexual harassment or abuse with regard to the celebrities whose facial features are superimposed into these videos.

Less talked about, however, are the implications for the performers whose bodies host the superimposed faces and whose videos are being pirated to produce deepfakes. Undoubtedly, the stigmatized and marginalized status of sex workers is a factor in their erasure from this conversation. Sex workers are too often excluded from public discussion of issues that affect them. (This was evident in the recent passage of FOSTA/SESTA legislation, which under the guise of combatting sex trafficking has effected a crackdown on sites that facilitate sex work, whether it is consensual or not.) But overlooking the porn performers whose bodies are used to create deepfakes also points to a broader issue with how bodies and sexuality — and their violation or abuse — are conceptualized with respect to the internet. Too often, intimate digital images of the body are treated as an inert documentation of the physical form rather than as a deeply felt extension of the self — as if only information were being made vulnerable rather than an integral aspect of one’s person.

The default response to digitally mediated sexual violations like so-called revenge porn, sextortion, and now deepfakes has been to frame them as matters of information management and privacy. For example, the authors of the foundational legal paper on the topic of nonconsensual pornography (a broader, more encompassing term for revenge porn) rely on such a framing. But historically, privacy has been a particularly fraught foundation for protecting women from violence and harassment; often it has protected men from accountability. Catherine McKinnon — though her politics are problematic in many other ways when it comes to women’s bodily autonomy — perhaps best articulated how privacy discourse, like other liberal values, fails to account for patriarchal structures, leaving women vulnerable. She argues that “the legal concept of privacy can and has shielded the place of battery, marital rape, and women’s exploited labor” by justifying noninterference in the domestic sphere, and concludes that in practice, privacy has been exercised as a right for men to be “let alone to oppress women one at a time.”

Not only has privacy been an obstacle to women seeking protection from harm; it has also been imposed on them as an obligation. The modern sexual double standard has made public sexuality acceptable and even celebrated for men while for women, privacy and “modesty” and withdrawal from the public sphere are often made imperative. Women who share aspects of their sexuality online face particular scorn, and when they experience violation, they are often met with victim-blaming and the digital equivalent of “she was asking for it with that outfit.”

Even refinements to the concept of privacy, like Helen Nissenbaum’s “context integrity,” which rejects a “public is public” attitude toward published materials in favor of recognizing the different expectations of exposure generated by different contexts, still retain a focus on information management. This perspective suggests that the body misappropriated in deepfakes and other images is just a kind of sensitive information, more like a password or a Social Security number than something fully integral to the self.

This, in turn, reflects a widespread tendency to treat digital representations on screens as “virtual” and less real, if not altogether unreal — a condition that Nathan Jurgenson has labeled “digital dualism.” It follows from the dualist perspective that bodies belong strictly to the physical world and are therefore insusceptible to harm in the digital world. But this does not correspond to narratives of those who have experienced digitally mediated sexual violations. Consider, for example, how Jennifer Lawrence talks about the experience of having nude photos stolen and leaked:

Those pictures were incredibly personal to me — and my naked body I haven’t shown on camera by choice — it’s my body. I felt angry at websites reposting them. […] I can’t really describe to you the feeling that took a very long time to go away, wondering at any point who is just passing my body around.

In a similar fashion, many targets of nonconsensual pornography describe the experience as more akin to sexual assault than to, say, pirated content. One explained in a CNN interview: “I describe it [as] similar to maybe the feeling of getting raped — you feel like you’re that exposed.” Another target told The Guardian: “The phrase ‘revenge porn’ trivializes what felt to me like rape.” Leah Juliett has spoken of the visceral impact that such violation has had on their relationship with their own body: “I exist in the gray space where a Facebook photo ends and my actual vagina begins. My body lives online. My breasts, my clavicle, my inner thighs feel bruised from the constant trading of hands.”

These narratives focus on bodily integrity. They insist that digital instantiations are not abstractions or mere representations of the body

Note the lack of distancing terms like “virtual” or “cyber” in their descriptions. Also absent are terms pertaining to what Nissenbaum calls “norms of information flow,” such as “publish,” “share,” or “disclose.” Survivors’ accounts of digitally mediated sexual violations focus squarely on the privileged relationship we have with our own bodies: our right to determine what happens to them and, above all, how other people relate to them. In other words, these narratives focus on bodily integrity. They insist that digital instantiations are not abstractions or mere representations of the body, somehow distant and removed, but extensions of it as well as the agency we express through it into different contexts.

There is precedent within the law for treating artificial extensions of the body as integral to the self. In the 1967 Supreme Court decision in Fisher v. Carrousel Motor Hotel, Inc., bodily integrity was interpreted as a

protection [that] extends to any part of the body, or to anything which is attached to it and practically identified with it. Thus contact with [a person’s] clothing, or with a cane, a paper, or any other object held in his hand will be sufficient … interest in the integrity of his person includes all those things which are in contact or connected with it.

This can be read as applying not only to the flesh-and-blood body but anything that embodies a conscious self and through which that self expresses agency, including pornographic images or videos — however stigmatized they may be in our sex-negative culture.

But social norms are late to the party. For decades now, science fiction like Neuromancer and Ghost in the Shell have tried to reimagine the boundaries of the self. As have social theorists: Describing her experience with phone sex work in the 1980s, Sandy Stone observed that “what was being sent back and forth over the wires wasn’t just information, it was bodies” — that phone sex operators are (in part) embodied by the medium through which they worked. More recently, in an essay on sexting, Sarah Nicole Prickett explains, “I can register words in my whole nerves… seduction is language, bodily or verbal.” In both examples, the authors talk about bodies being expressed and felt. These communications are integral to our self-perception.

Stone concludes that “virtual systems are [perceived as] dangerous because the agency/body coupling so diligently fostered by every facet of our society is in danger of becoming irrelevant.” In other words, we need to let go of the assumption that the essence of the self is confined to the flesh-and-blood body and instead recognize that anything through which we can express agency can become part of the self. Citing the example of a blind person who navigates space with a cane, phenomenologist Maurice Merleau-Ponty describes this process of bringing new objects into the bounds of the self as “incorporation,” observing that the cane comes to work no longer as a separate tool but an extension of the body through which a blind person can feel. Such extensions are no longer confined to the directly tangible but also encompass digital avatars — such as the online pics and profiles that Whitney Erin Boesel and I have previously likened to “digital prostheses.”

This perspective assumes that all interactions and experiences are mediated — that flesh itself is a medium. No interactions are any more or less “real” than others; they are just differently mediated, and this doesn’t make them any less integral. When someone posts a negative comment, we feel hurt; if we lend our phone to someone, we feel vulnerable; if our accounts are hacked, we feel attacked — the distinction between self and object is readily collapsed. This is also why, in practice, those who have experienced digitally mediated sexual violations speak of their bodies being exposed or violated.

If digital representations are extensions of the body, regardless of how they came to be, they should be respected as part of that body and afforded the same protections. In the context of deepfakes and other digitally mediated sexual violations, this means seeking justice on behalf of all women affected and not just those who conform to the social norms of modesty — the norms often baked in to the oft-championed concept of privacy.

Examining deepfakes through the lens of bodily integrity urges us to ask: What about the models who are being digitally decapitated? What about their right to determine what happens to their bodies? Celebrities whose faces have been superimposed on porn clips may be able to bring a civil suit against a someone who used their likeness for a deepfake, but at their own expense. Such costs will be prohibitive for most porn models, and even if it weren’t, the stigma associated with sex work means they’d likely receive little sympathy from a judge. Alternatively, prosecutors might attempt to shoehorn deepfakes into existing privacy law; however, porn performers who have already willingly published sexually explicit images are unlikely to be afforded these protections, having no “reasonable expectation of privacy.”

A law geared toward updating the concept of bodily integrity for the digital age would not distinguish between celebrities whose faces are removed from nonsexual contexts and porn performers working in an explicitly sexual context. But defending porn models from digitally mediated violation is a lot to expect from a legal system that still treats sex workers as unrapeable. So more practically, we can start with the informal norms and expectations we set for each other. Bodily integrity suggests that these performers, along with everyone else, have a right to protection from having representations of their bodies fundamentally altered without consent — something we should all strive to honor and protect.