On an overcast day, the light in the European Sculpture Garden of the Metropolitan Museum of Art is bright enough to make every visitor look like they’re carved from marble. Without shadows from clouds or dark corners, pores look smaller, eyes are whiter, hair shinier. It’s a calming, gratifying experience that breeds a certain kind of stoicism: During the preview for the Costume Institute’s latest show, “Manus x Machina,” which aims to explore the connection between handmade and machine-made fashion, press waited patiently for opening remarks, sitting on chairs that were slightly more elegant than the folding kind but not as enduring as pews, before being led into the Robert Lehman Wing, where the architectural firm OMA had built a smooth, gray multilevel cathedral inside the existing structure to house the collection. Slightly more sacred by virtue of being temporary, the space has the hush of a church, although the choir has been replaced by a loop of Brian Eno’s “An Ending (Ascent).”

Though the title of the exhibition positions an either/or question, it is neither a hard dichotomy nor a soft parallel. Visitors are asked to consider Man’s relationship to Machine, and Machine’s relationship to Man, as both relate to the limited but expanding definition of wearable technology. “Manus x Machina” is not interested in the wearable tech of science fiction: the cute, digitized manicures of Total Recall; the retractable claws of William Gibson’s Neuromancer; the equally weaponized flesh of David Cronenberg’s Videodrome (I always think of how, by the end of that movie, James Woods embodies the word handgun in an oozingly literal way). This is a fashion future envisioned as a better, smarter, prettier iteration of what we already recognize as clothing — and the machines here are not our enemies but our helpers, our companions, our friends.

Besides Andrew Bolton, head curator of the Costume Institute, “Manus x Machina” was co-chaired by Jony Ive, Apple’s chief design officer; Apple sponsored the event, together with Condé Nast and Vogue. Bolton began collecting with the goal of proving that man and machine, in fashion, have always and will always work together, and that the distinction between man- and machine-made is largely symbolic. During the opening remarks, he spoke about using the clothing in the exhibition like a DNA excavation, to show the individual genomes (threaded by a hand, or a needle) as less crucial than the final organism they comprise. The comparison to DNA takes fashion as something more elemental than what’s worn on the body. Each item in the exhibition is instructional, creating a timeline of fashion that is inherited — hereditary — as well as evolutionary. Every dress owes a familial debt to many before it; Issey Miyake’s pleating was given a row of its own beside similar designs by Mary McFadden and Mariano Fortuny from the early 20th century. Paternity, then, is something to consider: Are the dresses borne of their designers or of each other?

Each item in the exhibition is instructional, creating a timeline of fashion that’s genetically hereditary as well as evolutionary.

In Bolton’s reading, the designer matters a great deal. He noted that the classification binary in high-end fashion — ready-to-wear and couture — is largely symbolic as well. Couture takes handiwork as a given, although dresses that fit its legal definition (the label “haute couture” is enforced in France by the Paris Chamber of Commerce, and designers and brands are subject to review) really only have to be made to measure; they do not need to be entirely done by hand. Likewise, ready-to-wear is often manufactured en masse by machines, but not exclusively. With couture, the hands are, in Bolton’s words, an “unexamined component, or requirement” of the work. The assembly lines of ready-to-wear are dismissed as well, as though what matters in either case is the idea of the maker. Sewing machines, and the chemical processes that yield synthetic materials, are so invisible that they reinforce the primacy of the person. They have been subsumed into our ideas of natural, nonthreatening-to-humanity forms of production.

Technologies that presume to innovate — or worse yet, “disrupt,” in the preferred term of our time, which invokes distortion and damage — are often met with some hesitancy or weariness. They remove power from human hands and ask us to trust machinery or algorithms. For couture, a trade founded on the belief that humans (French humans) know best, this is an existential threat. But fashion thrives in the place between fear and boredom: The cycle of newness, ubiquity, and overexposure defines the life cycle of a trend’s genome. “Manus x Machina” tries to show that wearable technology is not so scary after all; it’s part of a familiar family tree.

To date, the most notable forms of wearable technology are lucky to be rated as simple luxuries rather than foolish indulgences. “Manus x Machina” is not interested in the billion-dollar investments of venture capitalists, or the hopeful contributions of tech companies so enamored with progress they lose sight of the point. Google Glass was one such example. A smartphone that rested on the wearer’s face, with all the applications of a smartphone, did not play well with consumers. In January 2015, after disappointing sales and criticism related to privacy concerns (not to mention general aesthetics; it was really ugly), Google stopped sales entirely. They’ve since filed a new patent for a different version of the product, aimed at businesses rather than consumers. Apple Watch — Jony Ive’s pet project — might become another.

Ive, in his speech, spoke about his father, calling him a “craftsman.” Hence, “I was raised with the fundamental belief that it is only when you personally work with the material with your hand that you come to understand its true nature, its characteristics, its attributes, and, very importantly, its potential.” At Apple, he said, “many of us believe in the poetic possibilities of the machine … We have tremendous respect and admiration for what is made by the hand.” The Apple Watch has been a sign of the struggle between the company’s interests and its customers’ demands: The product was too concerned with innovation and not concerned enough with the practical. (The exact numbers have been kept private, but analysts have suggested that sales are … not good.) Ive is quick to note that the first few generations of iPods and iPhones were drastically different from the ones that followed, and that it’s still too early to tell if customers will definitively embrace or reject his watch. Despite the seemingly relentless speed at which the two industries operate, fashion and technology often want to remind us that patience is a virtue and that we should put our faith in their visions. The safe space of the exhibition protects wearable technology from both pop culture fears and the kinds of criticism that prevent consumption. It’s in Apple’s best interest to change minds rather than change its products — leaders, spiritual or otherwise, don’t often recover after admitting any kind of defeat.

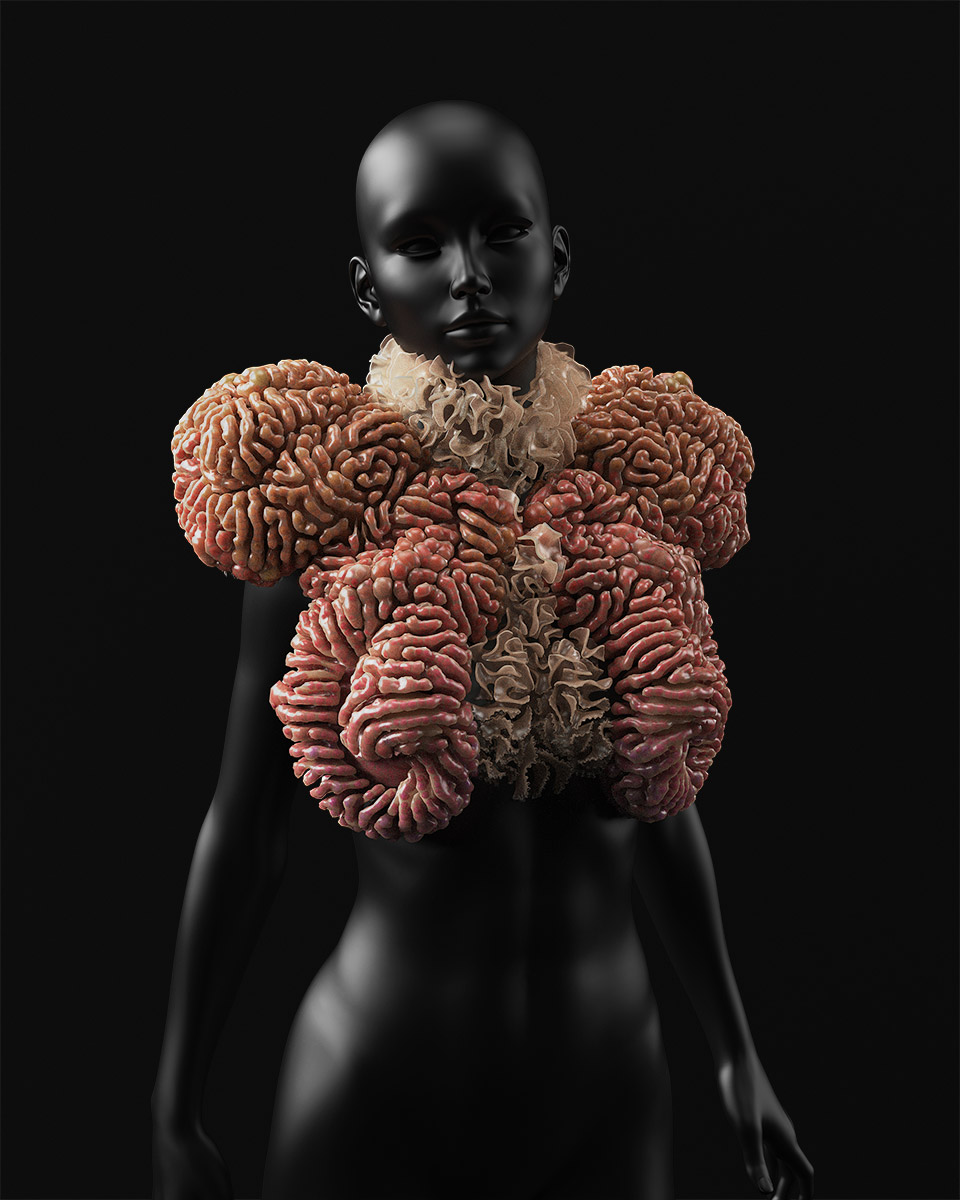

“Manus x Machina” revolves around the Encyclopédie, ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, written by Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d’Alembert in 1751, the text that encapsulated the central theories of the French Enlightenment. As the exhibition copy points out, Diderot and d’Alembert wanted craft — then known as the “mechanical arts” — to be taken as seriously as any of the other arts or sciences: “The elevation of these and other métiers served as an incendiary challenge to established prejudices against manual labor, biases that the authors sought to refute by showing the creativity and complexity such work involved.” The métiers that comprise fashion design — like embroidery, lace, pleating, leather, feathers, and artificial flowers — guide the exhibition, with clothing grouped according to trade. The fabric camellias of Chanel, a long-running motif in the brand’s history, are paired with a Christopher Kane RTW outfit from Spring/Summer 2014, a sweater and skirt that has laser-cut flower appliqués with embroidered labels diagramming the different parts of the flower. (The overall effect is like wearing a very pretty science textbook.) In featherwork, a 2013 Iris van Herpen piece blended silicon and cotton in a 3-D printer to create a fuzzy peach of a dress, two hawk-like birds extending from the shoulders with open mouths that seem to warn onlookers about touching the goods. Van Herpen is perhaps the best contemporary designer working with fabrics particular to 3-D printing rather than replicating conventional ones. The fine feathers of this dress reminded me more of AstroTurf than any organic material known to man or machine, but nonetheless seemed adjacent to nature.

The exhibition’s central piece occupies an entire room inside the domed cathedral. From the Fall/Winter 2014 Chanel Haute Couture collection, Karl Lagerfeld’s wedding dress showpiece needed that much space just to accommodate its 20-foot-long train covered in a pixelated gold baroque pattern. The wall text boasts of the man-machine confluence at work within this single dress: Made of scuba knit (synthetic), the pattern was originally drawn by hand (Lagerfeld’s), then digitally rendered to achieve the desired effect (randomization). Chanel ateliers used a heat press for rhinestones and painted the gold by hand. It’s the first thing visitors see upon entering, and seeing it requires a full lap: It’s stunning. I did wonder about the choice to venerate Lagerfeld as the most human element of the dress. Lagerfeld is a very hard-working and talented designer who has been, for most of his career, a caricature of himself, more a carbon copy of listable eccentricities — his perpetual sunglasses, stiffly starched high shirt collars, beloved white Birman cat, and bizarre soundbites (most recently about feminism and Cuba) — than a man.

Conglomerates buy and sell fashion houses, and designers and creative directors shuffle around at a pace too rapid to compare to a game of musical chairs. (In the past two years, designers Hedi Slimane, Alber Elbaz, Raf Simons, Alexander Wang, and Francisco Costa have either resigned or been removed from their roles at Yves Saint Laurent, Lanvin, Dior, Balenciaga, and Calvin Klein respectively.) Nonetheless, while fashion venerates Great Men at the helm of great houses, the cults of Great Men at the helm of great tech companies are even stronger. Ive, in particular, inspires his own kind of following: He’s often described as a “rock star” by publications like Wired and Gizmodo, and a 2015 profile in the New Yorker said he was, as a man, Apple’s greatest product. His aesthetic sensibility is so widespread that it appears ubiquitous. Ive has been an employee of Apple since 1992; if you are of a certain age cohort, you might be most familiar with his iMac G3, the desktop computer that came in a wide range of jewel-toned colors and seemed to appear in the bedrooms of every teenage character on television between 1998 and 2002. But now, he’ll live and die by the Apple Watch, the company’s tentative entry into wearable technology and, crucially, a product that Ive had to make without the oversight of Steve Jobs, who died before it was completed. Jobs was a boss to Ive, but to Apple consumers and die-hard fans he was a prophet, if not a god.

Despite their seemingly relentless speed, fashion and technology often want to remind us that patience is a virtue

Diderot and d’Alembert were trying to elevate craft itself to the level of an intellectual profession. Likewise, the exhibition takes the question “What is wearable technology?” as an opportunity to ask what isn’t — a reminder that our ideas about which forms of innovation deserve worship have more to do with power than “progress.” The small computer strapped to your wrist is labeled wearable technology but rarely fashion; Hussein Chalayan’s Fall/Winter 2011 fiberglass dress (which the wearer dons through a rear-access panel and then operates via remote control) is labeled fashion but rarely wearable technology. “Manus x Machina” offers a clear resolution: Embrace all technology equally, and let the microchips fall where they may.

The effect, like a skylight, suggests an unexpected source of illumination: The machines are given life by human and corporate genius. Maybe the idea of a wearable computer is not quite as strange as reluctant customers seem to think it is. Maybe wearable tech, as presented by one of the most powerful brands in the world, was on you all along. Even if Apple’s products aren’t on display, they are everywhere. The lower levels of the cathedral rely on strategically placed spotlights, and the resulting darkness means that the dresses stand under the long shadows of many iPhones, held up by visitors taking photos or using the encyclopedic functions available with the tap of a thumb. Maybe here, in this hallowed structure within the hallowed halls of the Met, ordinary objects like clothes and phones can become sacrosanct. Great Men, great architecture, and great branding converge in a holy trinity.

Apple’s sponsorship, and Ive’s involvement, is restrained and barely noticeable in the exhibition itself, save for the subtle logo treatments in the Met’s communications. The cathedral does, in many ways, bear a resemblance to the iconic Apple store designs — sparse, clean, reliant on natural light — but that is a question of influence, not intrusion. Apple’s design principles can be felt in almost all areas of contemporary design; companies have a tendency to react rather than revolt. The aesthetic and functional simplicity of Apple’s products has always suggested a certain paternalism, inspired less by how people use their phones than by how Apple’s directors and engineers think people should use their phones. Directing consumer preferences is about power as much as invention. To the devout, this is intelligent design: evolution guided by Ive’s divine hand.

Despite the title, this exhibition is not about the hands of men. It’s about which men have the hands of gods. The stoic beauty on display inside this temporary cathedral is the light, and we are, I suppose, the clay, shaped by men on a righteous — if winding — path. Like the philosophers of the Enlightenment, who advised deism when atheism proved too politically contentious, “Manus x Machina” suggests we worship not God the Creator, but God the Creative Director.