Here in the golden-brown (think: L.A. smog) age of capitalism, the tech industry is poised, if not determined, to take over for our inefficient, corrupt government. American lawmakers’ failure to enact sensible health care reform in the Obama years, stripping his proposed single-payer program to a neutered “we’ll take it” patch job, is promised to worsen under the Trump administration. But as hope for sensible reform diminishes, the demand for cheap caregiving is growing wildly out of proportion. Capitalism’s solution is, predictably, to automate labor.

Remote health care services are already on the rise, streamlining the doctor-patient relationship for everything not requiring in-person contact. Virtuwell and Heal.com can replace visits to your primary care doctor; Curology lets you chat and send selfies to a dermatologist, who then prescribes a custom face cream for a low monthly subscription fee; Mindstrong Health, pioneered by neuroscientist Thomas Insel (previously of Verily, Alphabet’s life sciences division), tracks your smartphone use to diagnose and treat behavioral health disorders; and Nurx prescribes birth control and delivers it to your door — no doctor’s visit required.

The thought of being tended to by machines is just too painful

The next big thing is RoboCare: artificially intelligent robots taking the place of nurses, particularly for the elderly and disabled. RoboCare, inevitably a buzzword analogous with ObamaCare, is actually the name of a company in France that makes “telepresence robots.” Current models resemble an iPad on a Segway. They help facilitate care for those lacking autonomy, and they will also play games with you. The marketing copy on RoboCareLab.com calls the robot a “new addition to the family” — it facilitates living at home, as opposed to in an assisted-living facility. Robear, made in Japan, can gently lift a patient in and out of bed or a wheelchair, and has an adorable teddy-bear head to boot. Engineers at the Georgia Institute of Technology are developing caregiving robots including GATSBII (GATech Service Bot with Interactive Intelligence) for delivering medication and water, as well as reaching for and retrieving objects; and Cody, who gives sponge baths.

Without the constant demands of a mortal coil, a robot with AI could conceivably be a superior doctor to a human one. (A new AI platform, created by the Human Diagnosis Project, already lets doctors double-check the veracity of a diagnosis in real-time using crowdsourced data.) But robots, and other automated health care services, don’t necessarily address one of the major causes of physical and psychological illness and early death: loneliness.

Care work is one of those at-first-glance oxymorons that, like “emotional labor,” disproportionately falls to women, particularly women who are vulnerable, financially or socially. Researchers at Stanford University’s Clinical Excellence Research Center coined the term “daughter care,” describing it as the most reliable, affordable source of care for dementia patients in particular. Caregiving is low-income work, increasingly relegated to immigrants: “The number of immigrants in direct care ballooned from 520,000 in 2005 to approximately one million in 2015, including those who work independently through state home care programs,” according to a recent article in the New York Times. Politically speaking, the current administration is setting up for an even worse pitfall with hostile immigration and deportation policies.

We are already alarmingly unprepared to take on the dramatic demand growth for caregivers: In 2015, 8.5 percent of people worldwide — about 617 million of us — were aged 65 and over, according to a recent Census Bureau report commissioned by the National Institutes of Health. That percentage will double to at least 17 percent of the world’s population — 1.6 billion — by 2050. That’s only half the problem, one Reuters columnist notes, as “roughly half of demand for care will come from younger, disabled people.” And by 2030, there will be a drastic national shortage of certified nursing assistants and in-home caregivers, says MIT professor Paul Osterman in the book Who Will Care for Us: Long-term Care and the Long-Term Workforce (2017). This includes an expected shortage in the most common source of caregiving for the low-income and the uninsured: unpaid family members and friends, predominantly women.

Caregiving is a decidedly unglamorous line of work, and there are certainly compelling economic and workers’-rights arguments to be made in favor of disembodied care. “RoboCare” may seem bleak, but we cannot keep up with demand without raising wages. “People are expensive — at least compared to automated, data-driven chatbots that could give advice and diagnose diseases without needing a salary or a college degree,” writes Stephanie M. Lee at Buzzfeed. In addition to being undercompensated, care work is physically and mentally overwhelming and socially isolating: labor conditions that put the health of the caregivers themselves at risk.

Changing how we care for our sick, elderly, and disabled would be liberating for undercompensated laborers and uncompensated family members alike — the problem is that the thought of being tended to by machines just too painful. While we continue to innovate new ways to depend less upon one another, it is painfully apparent just how dependent we are on one another, how viscerally the experience of human-to-human physical contact connects with us emotionally, and how inextricable our emotional experience is from our physical one. Caregiving extends into all aspects of life, even sex work — an integral square in the societal fabric that, while uncomfortable put side-by-side with caring for the elderly and disabled, we should be equally concerned about. As strange as it is to ask, how do we reconcile the human need for care with the human need for other humans?

Loneliness is a deadly epidemic, as Dhruv Khullar writes in the New York Times, that disproportionately impacts the elderly, the mentally and physically disabled, and those suffering mood disorders like depression. “Loneliness and weak social connections are associated with a reduction in lifespan similar to that caused by smoking 15 cigarettes a day and even greater than that associated with obesity. But we haven’t focused nearly as much effort on strengthening connections between people as we have on curbing tobacco use or obesity,” former U.S. surgeon general Vivek H. Murthy writes in the Harvard Business Review. “Loneliness is also associated with a greater risk of cardiovascular disease, dementia, depression, and anxiety.” The UC Berkeley Social Networks Study found that young adults “reported twice as many days lonely and isolated than late middle-age adults, despite, paradoxically, having larger networks,” which goes to show social wellness arises not from perceived bonds, or the quantity thereof, but by the strength of one’s relationships.

In 2016, a PSA by the Society of Saint-Vincent-de-Paul portrayed the loneliness of an elderly widow’s life with B.E.N. (Bionically Engineered Nursing), an anthropomorphic robot caregiver, in the bleak style of Black Mirror. While B.E.N. is programmed to cheer her up, he’s got a tin ear (pun intended) — his oblivious friendliness is unempathetic verging on aggressive, and his mechanical gestures of affection only add to her loneliness. Caregiving is a relational as well as professional engagement, whether that care is being given by a relative or a hospital employee; and automated services, provided, presumably, by machines incapable of forming emotional bonds with the humans they’re assigned to, don’t actually provide the sort of companionship that can stave off loneliness.

Is there a world in which technology can solve the loneliness problem?

This places us in a feedback loop of ethically unsatisfiable problem-solving: grimly calculating the costs against the benefits of not having to spend time and effort with one another. Is there a world in which technology can solve the loneliness problem? Of course, an episode of Black Mirror has already gone there, proposing virtual reality as the solution. In “San Junipero,” VR-augmented caregiving is touchingly portrayed through two people who’ve lost their physical autonomy, but are able to live young, free, sexy lives forever in literal paradise. If the only solution to loneliness is human contact, then facilitating an emotionally satisfying experience — even at a distance — should be a top priority for those developing the future of how we care for one another.

If one must be alone, they must not necessarily be lonely. According to a 2017 survey conducted by by the Pew Research Center called “Automation In Everyday Life,” people may not mind technology that enables them to live alone without human assistance. Respondents who were not interested in having a robot caregiver “overwhelmingly mention[ed] one concept over all others: namely, that trusting their loved ones to a machine would cause them to lose out on an element of human touch or compassion that can never be replicated by a robot.” But even elderly subjects of the survey indicated positive interest in the increased privacy and autonomy a robot caregiver would offer, and the survey raised the possibility that a robot caregiver could be monitored remotely by a human, to which many responded affirmatively.

In reality, a robot caregiver like B.E.N., contrary to the sad portrayal in the video, could do wonders for patients by slow-dancing with them and providing other forms of physical contact, not to mention the more difficult parts of caregiving. Though robots can’t replace human contact, they could supplement it, taking on the most laborious and emotionally taxing jobs, while allowing for a greater sense of independence and dignity.

Touch is less literal than we might assume, and personal contact not always a matter of physical contact

Touch is “the first of the senses to develop in the human infant, and it remains perhaps the most emotionally central throughout our lives,” writes Maria Konnikova in the New Yorker, and it is more nurturing than social connection alone; Konnikova alludes to a study by the Touch Research Institute at the University of Miami’s Miller School of Medicine, which found massage had far more “emotional and cognitive benefits” than purely conversational social visits. Of course, it is possible to enjoy non-human, or remote, forms of touch.

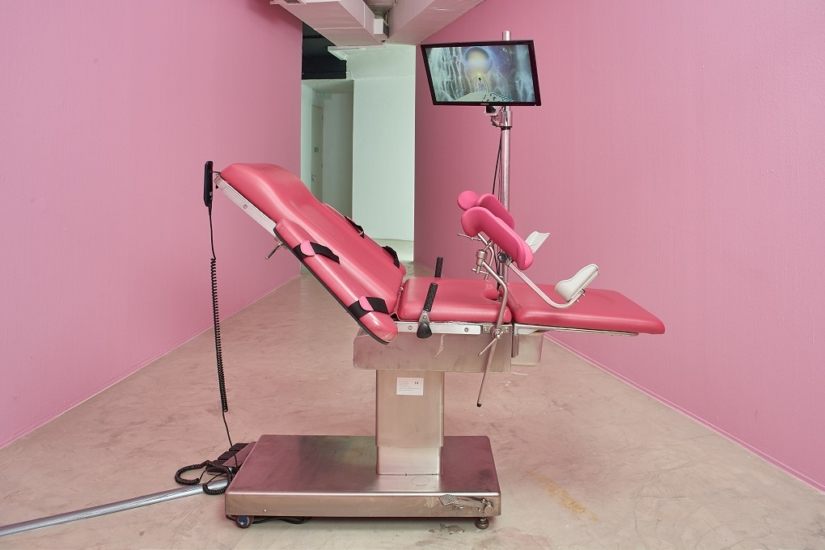

There are devices that make long-distance physical contact possible, albeit at the moment primarily for sex: remote-controlled vibrators, his-and-hers masturbators that sync through an App, and of course, RealDolls. There is a fine line between companionship-and-caregiving robots and sex robots — in Japan, companionship robots like Paro are touted to save the elderly and infirm from loneliness — although the latter has been subject to much taboo. Movies and television frequently depict human-to-machine relationships as unhealthy or doomed to failure, but often the AI is meant as a foil for a human unwilling or unable to form healthy relationships with other autonomous adults. Machines are just as often employed to bring people together.

Touch is less literal than we might assume, and personal contact not always a matter of physical contact. In many ways we are already adapting to intimacy at a distance, and learning to associate new sets of physical responses with togetherness — the crick in my neck as I gaze at the screen becomes associated with the closeness of video chat, or the thrill and urgency of rapid-fire texting. Current, real-life proposals imagine a medically useful robot that meets human needs — the ideal proposal would seek to augment, not to replace the necessity of being among other people. We still need each other.

This essay is part of a collection on the theme of PRIVATIZATION. Also from this week, David A. Banks on the history of anti-bus branding.