American presidential campaigns, we have rediscovered, are not in good faith. They are more performance than policy. They manipulate the media rather than articulate a philosophy of governance. The candidates are brands, and the debates have almost no discussion of ideas or positions, let alone much bearing on what being president actually requires. Instead, debates signify “politics” while allowing for depoliticized analysis: They are about assessing the candidate’s performance, style, tone, rhythm, posture, facial control, positioning with respect to cameras, and so on. What they say matters only with respect to how they said it: Did they convey conviction? Did they smile enough?

The candidates and those who fund them are as invested in these same campaign-ritual fictions about the electoral system’s underlying dignity as the reporters are. And there is nothing profound anymore in demystifying this. Astonished dismay at the lack of substance in presidential politics, driven in part by some inherently cheapening new media technology, has become as ritualized as the rest of the process, a point that pundits have been making at least since historian Daniel Boorstin published The Image, two years after telegenic Kennedy’s election over pale, beady Nixon. Joe McGinniss’s The Selling of the President 1968 described Nixon’s sudden interest in marketing through his next presidential run. Then, after nearly a decade of a president who was a movie actor, Joan Didion’s dispatch from the 1988 campaign trail, “Insider Baseball,” described presidential campaigns as merely media events, made to be covered by specialists “reporting that which occurs only in order to be reported” — a reiteration of Boorstin’s concept of the “pseudo-event.” Remember, too, George W. Bush’s Mission Accomplished stunt — essentially a campaign stop even though it wasn’t an election year — and more recently, the furor over the Roman columns erected for Obama’s 2008 convention speech.

So it has been clear for decades that presidential politics have turned toward the performance of an image. But away from what reality? Boorstin admits that he doesn’t have a solid idea: “I do not know what ‘reality’ is. But somehow I do know an illusion when I see one.” Boorstin takes refuge in the assumption that the average American voter is dumb and uninterested in anything more than the surface impression and incapable of reasoning about the substance of any political position. Marshall McLuhan echoed this view in his widely quoted claim that “policies and issues are useless for election purposes, since they are too sophisticated.”

Theories like Boorstin’s may be strong in describing how we construct an artificial world, but they are often compromised by their nostalgic undertow. We might believe a preceding era was more “real,” only to find that that generation, too, complained in its own time about the same sorts of unreality, the same accelerated, entertainment-driven reporting and bad-faith politics. This analysis has been rote ever since, complemented by the notion that the media dutifully supplies these highly distractible audiences the ever increasing amounts of spectacle they demand.

As media outlets have multiplied and news cycles have accelerated, the condition has worsened: Our immoderate expectation that we can consume “big” news whenever we want means that journalists will work to give it to us, to make the reality we demand. The television, and now the social media “trending” chart, gets what it wants. All this coverage, ever expanding into more shows, more data, more commentary, and more advertisements, come together to form the thing we’ve accepted as “the election.”

It is no accident that Trump, at many of his rallies, used the theme from Air Force One, a movie about a president

In this process, image-based pseudo-politics don’t come to replace real politics; the real comes to look like an inadequate image. Boorstin argued that, for example, the image of John Wayne made actual cowboys looked like poor imitations. (This is what Jean Baudrillard, writing after Boorstin, meant by “simulation.”) Similarly, the heightened media coverage of campaigns has made ordinary politics — eating pie, kissing babies, and repeating patriotic bromides — seem insufficient, underwhelming. It’s no accident that in the 2016 election, we got a candidate that gave us more and more outrageous news, a constant catastrophe perfectly tuned to our obsessive demand for horrifically fascinating entertainment. We might have hated every moment, but we kept watching and clicking, reproducing the conditions for the same thing to continue in the future.

If a politician’s ability to get covered becomes their most important qualification, it flips the logic of campaigning: The presidency is merely the means to the end of harnessing attention. The distinction between a campaign and how it is covered is unintelligible and unimportant. Hence, a lot of the media coverage of the 2016 election was coverage of how the campaigns tried to get themselves covered. For instance, much of the news about Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton was about the image they created, and how Trump specifically marketed and branded himself differently than those who came before, what conventions he happened to be violating. For much of the past two years, commentators would more often giggle at the way Trump’s affect violated campaign norms of image maintenance than discuss his bigotry and the white nationalism that preceded and fueled his rise.

Playing to the circularity of this, Trump campaigned by discussing his campaign process. Like a news-channel talking head, he spent many minutes at his rallies on poll numbers. He provided a similar running commentary on the debate stages, remarking about the venue, the crowd, and the performance of the moderators. He remarked on who was having a good or bad night, whose lines had or hadn’t landed, and analyzed his own performance as it was happening. He was even quick to point out to Hillary Clinton, in real time, that she shouldn’t have reused a convention zinger again in a debate.

With his steady supply of metacommentary, Trump embodied the pundit-candidate. While his repugnant politics have had material consequences, he campaigned more explicitly at the level of the symbolic, of branding, of the image. His representation of himself as the candidate who rejects political correctness epitomized this: How he talked about issues was trumpeted by the candidate and many of his supporters as the essential point, more important than any policy positions he could be irreverently talking about.

Much of the coverage of Trump followed suit: It wasn’t punditry about a politician, but punditry about punditry, for its own sake. Trump’s viability as a candidate demonstrates how far the familiar logic of the image has come, where a fluency in image-making is accepted to an even greater degree as a political qualification in its own right, independent of any mastery of policy or issues. Campaigning according to the image is not just using polls to pick popular stances but to relegate stances into fodder for talking about polls.

When politicians are concerned mainly with producing an “image” — not with what world conditions are actually there, which are heavy and can only change slowly and with great coordinated effort, but with what you see, what they want you to see, what you want to see — they are dealing with something that is light, something easily changed, manipulated, improved, something that flows from moment to moment. Trump appeared to understand intuitively the logic of lightness, that a candidate need only provide an image of a campaign.

Accordingly, he resisted building up much of the standard campaign infrastructure, from the provision of a detailed platform on up to the development of an adequate ground-game operation to get out the vote on Election Day. These too are heavy, like a locomotive tied to its tracks. Trump’s campaign floated above this, going wherever media expectations suggested it should go. Because there was so little depth anchoring the candidate and so little campaign machinery to weigh him down, Trump’s white nationalism nimbly flowed across various stances and issues, much like a fictional president being written and rewritten in a writers’ room. He could center his campaign on scapegoating Mexico and promising a border wall but then shift toward scapegoating Islam and preventing Muslims from entering the country in the wake of terrorist attacks, and then became the “law and order” candidate after police violence and anti-police protests dominated the news. It was no accident that Trump, at many of his rallies, used the theme from Air Force One, a movie about a president.

The role of a campaign apparatus is not to conceal how its candidate is “manipulating an image” but to emphasize the degree to which everything is image

If the contest is between images, candidates only need an improvised script; everything else leads to inefficiency. The role of a campaign apparatus, from this perspective, is not to conceal how its candidate is “manipulating an image” but to emphasize the degree to which everything is image, including, supposedly, the election’s stakes. By being so transparent in playing a part, by making the theatrics of it all so obvious, Trump offered catharsis for viewers so long served such obvious fictions as “my candidacy is about real issues” and “political coverage cares about the truth.” Accompanying any oft-repeated lie is a build-up in tension, of energy that gets tied up in sustaining it. Part of the Trump phenomenon was what happens when such energy is released.

It’s easy to see how Trump’s rise was the culmination of image-based politics rather than some unprecedented and aberrant manifestation of them. Yet much of the political apparatus — conventional politicians and the traditional media outlets accustomed to a monopoly in covering them — still rarely admits this out loud. Instead, it tried to use Trump’s obvious performativity as an opportunity to pass off the rest of the conventional politics it has been practicing — the image-based, entertainment-driven politics we’ve been complaining about since Boorstin and before — as real. Perhaps it was more real than ever, given how strenuously many outlets touted the number of fact-checkers working a debate, and how they pleaded that democracy depends on their gatekeeping.

Before the campaign began, comedian Seth Meyers quipped that Trump would not be running as a Republican but as a joke. Commentators said he had no chance to become the Republican nominee — or about a two percent chance, according to statistician Nate Silver. The Huffington Post decided to single out Trump’s campaign and label it “entertainment” instead of “politics,” as if the rest of the candidates were something other than entertainment. Many pundits put forward the idea that Trump was trolling, as if candidates like Ben Carson and Ted Cruz were actually preoccupied with pertinent political topics, and the press coverage of them was fully in earnest.

Trump was hardly a troll: He didn’t derail a conversation that was in good faith; he gave the media exactly what it demanded. He adhered to the unspoken rules of horse-race presidential-election coverage with a kind of hypercorrectness born of his respect for the reality-show format. The race was long made to be a bigger reality show, demanding more outsize personalities and outrageous provocations and confrontations. Trump may not have been a good candidate, but he made for an entertaining contestant.

The fact that Trump was a performer manipulating audiences without any real conviction in anything other than his own popularity made him more like other candidates, not less. Trump wasn’t uniquely performative, just uniquely successful at it. If the performance was bombastic, so much the better for its effectiveness. After all, the image is the substance.

In contrast, Obama’s performance as a symbol of hope and change was more coy and less overtly pandering. It more closely mimics what McGinniss, citing Boorstin, described in The Selling of the President 1968:

Television demands gentle wit, irony, and understatement: the qualities of Eugene McCarthy. The TV politician cannot make a speech; he must engage in intimate conversation. He must never press. He should suggest, not state; request, not demand. Nonchalance is the key word. Carefully studied nonchalance.

McGinniss says selling the president is like building an Astrodome in which the weather can be controlled and the ball never bounces erratically. But Trump took a very different approach; he wasn’t nonchalant, and he rarely hinted or suggested. He was consistently boisterous. In 1968, to build a television image was to make someone seem effortlessly perfect. Trump was instead risk-prone, erratic, imperfect, and unpredictable. Playing to an audience more savvy about image-making, Trump knew his erratic spontaneity played like honesty. In appearing to make it up as he went along, his calculations and fabrications seemed authentic, even when they consisted of easily debunked lies. It feels less like a lie when you’re in on it.

Some of the most successful advertisements make self-aware reference to their own contrivances. In this way Trump was like P.T. Barnum: He not only knew how to trick people but how much they like to be tricked. Deception doesn’t need to be total or convincing. Strategically revealing the trick can be a far more effective mode of persuasion.

We shouldn’t underestimate how much we like to see behind the curtain. There’s some fascination, morbid or not, in how things are faked, how scams are perpetrated, how tricks are played. The 2016 campaign gave us exactly what we wanted.

Any national election is necessarily chaotic and complex. The fairy tale is that media coverage can make some sense of it, make the workings of governance more clear, and thus make those in power truly accountable. Instead, the coverage produces and benefits from additional chaos. It jumps on the Russian email hacks for poorly sourced but click-worthy campaign tidbits, even as, according to a cybersecurity researcher quoted in a BuzzFeed report, they are likely driven by Russian “information operations to sow disinformation and discord, and to confuse the situation in a way that could benefit them.” Or as Adrian Chen wrote in his investigation of the Russian propaganda operation, Internet Research Agency:

The real effect, the Russian activists told me, was not to brainwash readers but to overwhelm social media with a flood of fake content, seeding doubt and paranoia, and destroying the possibility of using the Internet as a democratic space … The aim is to promote an atmosphere of uncertainty and paranoia, heightening divisions among its adversaries.

If that is so, the U.S. news media has been behaving like Russian hackers for years. From 24-hour television to the online posts being cycled through algorithms optimized for virality, the constant churn of news seems to make everything both too important and of no matter. Every event is explained around the clock and none of these explanations suffice. Everything can be simultaneously believable and unbelievable.

The race was made a bigger reality show, demanding more outsize personalities

It’s been repeated that the theme of the 2016 campaign is that we’re now living in a “post-truth” world. People seem to live in entirely different realities, where facts and fact-checking don’t seem to matter, where disagreement about even the most basic shape of things seems beyond debate. There is a broad erosion of credibility for truth gatekeepers. On the right, mainstream “credibility” is often regarded as code for “liberal,” and on the left, “credibility” is reduced to a kind of taste, a gesture toward performed expertism. This decline of experts is part of an even longer-term decline in the trust and legitimacy of nearly all social institutions. Ours is a moment of epistemic chaos.

But “truth” still played a strong role in the 2016 campaign. The disagreement is how, and even if, facts add up to truth. While journalists and other experts maintain that truth is basically facts added up, the reality is that all of us, to very different degrees, uncover our own facts and assimilate them to our pre-existing beliefs about what’s true and false, right and wrong. Sometimes conspiracy theories are effective not because they can be proved but because they can’t be. The theory that Obama was not born in the United States didn’t galvanize Trump’s political career because of any proven facts but because it posed questions that seemed to sanction a larger racist “truth” about the inherent unfitness of black people in a white supremacist culture.

Under these conditions, fact-checking the presidential campaigns could only have been coherent and relevant if it included a conversation about why it ultimately didn’t matter. Many of us wanted a kind of Edward R. Murrow–like moment where some journalist would effectively stand up to Trump, as Murrow did on his news program with Joseph McCarthy, and have the condemnation stick. But our yearning has precluded thinking about why that moment can’t happen today. It isn’t just a matter of “filter bubbles” showing people different news, but epistemic closure. Even when people see the same information, it means radically different things to them.

The epistemic chaos isn’t entirely the media’s fault. Sure, CNN makes a countdown clock before a debate, and FiveThirtyEight treated the entire campaign like a sports event, but there was a proliferation of substantive journalism and fact-checking as well. Some blamed Trump himself. Reporter Ned Resnikoff argues this about Trump and his advisers:

They have no interest in creating a new reality; instead, they’re calling into question the existence of any reality. By telling so many confounding and mutually exclusive falsehoods, the Trump campaign has creative a pervasive sense of unreality in which truth is little more than an arbitrary personal decision.

But as much as Trump thrived within a system sowing chaos and confusion, he didn’t create it. He has just made longstanding dog-whistle bigotry more explicit and audible.

The post-truth, chaos-of-facts environment we have today has as much to do with how information is sorted and made visible as with the nature of the content itself. For example, in the name of being nonpolitical, Facebook has in fact embraced a politics of viral misinformation, in which it passively promotes as news whatever its algorithms have determined to be popular. The fact of a piece of information’s wide circulation becomes sufficient in itself to consider it as news, independent of its accuracy. Or to put it another way, the only fact worth checking about a piece of information is how popular it is.

Trump exploited this nonpolitical politics by taking what in earlier times would have been regarded by the political-insider class as risks. He would read the room and say what would get attention, and these “missteps” would get reported on, and then it would all get thrown into the churning attention machinery, which blurred them in the chaos of feeds that amalgamate items with little regard to their relative importance and makes them all scroll off the screen with equal alacrity. The result of having so much knowledge is the sense of a general mess. More and more reporting doesn’t open eyes but makes them roll.

The proliferation of knowledge and facts and data and commentary doesn’t produce more understanding or get us closer to the truth. Philosopher Georges Bataille wrote that knowledge always comes with nonknowledge: Any new information brings along new mysteries and uncertainties. Building on this, Baudrillard argued in Fatal Strategies that the world was drowning in information:

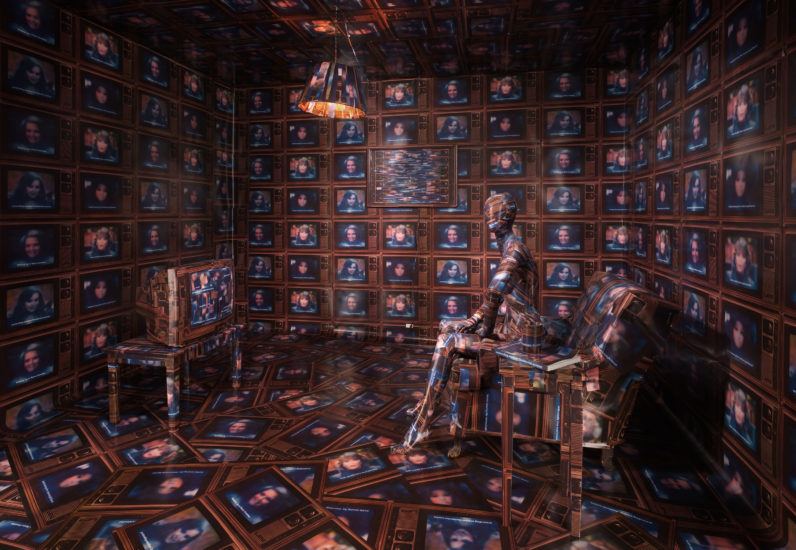

We record everything, but we don’t believe it, because we have become screens ourselves, and who can ask of a screen to believe what it records? To simulation we reply by simulation; we have ourselves become systems of simulation. There are people today (the polls tell us so!) that don’t believe in the space shuttle. Here it is no longer a matter of philosophical doubt as to being and appearance, but a profound indifference to the reality principle as an effect of the loss of all illusion.

Media produce not truth but spectacle. What is most watchable often has little to do with accuracy, which conforms to and derives from spectacle and remains inconclusive. The media produce the need for more media: The information they supply yields uncertainty rather than clarity; the more information media provide, the more disorientation results.

Trump helped these streams scroll even faster. He did not have to be right but instead absorbed the energy sparked by being wrong. He wasn’t the TV candidate or the Twitter candidate but a fusion of media channels, each burning at their core to accelerate. For example, cable news networks put members of the Trump campaign on TV ostensibly to tell “the other side,” yet their uniform strategy was to yell over the conversation with statements that often contradicted what the candidate himself was saying. They would be invited back the next day.

The 2016 election showed once again that journalism’s role is not to clarify the chaos around politics. Rather, an election and its coverage lurch along in a frothing, vertigo-inducing symbiosis. Every news event is at once catastrophic and inconsequential. War and terror seems everywhere and nowhere. Sociologist Zygmunt Bauman calls this a “liquid fear,” nihilistic in its perpetual uncertainty. Such fear fosters demand for a simple leader with simple slogans and catastrophically simple answers.

Perhaps we’ve come too close to the sun. The first rule of virality, after all, is that which burns bright burns fast. And the news cycle spins so rapidly we can’t even see it anymore. In this campaign, virality had nothing left to infect. Our host bodies were depleted, exhausted. The election ended too soon, well before Election Day. Amid this attention hyperinflation, can the currency of news be revalued?

If you push something too far along a continuum in one direction, it inevitably becomes its opposite. Perhaps the next election can’t produce anything as outrageous as Trump. We’ll return to politics as usual, to the performance of “issues” and “debates” that will seem more fully in good faith than before, in comparison to the embarrassment of this cycle. The election process will be as contrived and image-centric as ever, but we’ll be desperate to make it great again.