As interest in NFTs burgeoned over the past year, the images associated with the tokens began escaping the confines of their native digital medium and showing up in physical public spaces. Examples abounded: Street murals depicting Bored Apes and other popular NFTs appeared in major cities — Miami, San Francisco, Los Angeles — sometimes alongside art fairs or cryptocurrency events. The Strokes played an exclusive concert in Brooklyn for Bored Ape owners, as part of a week-long conference in which participants jovially spread the ape imagery (and that of other NFTs) throughout the city. Screen-laden NFT galleries began opening alongside their traditional counterparts in downtown New York and elsewhere. Signs and billboards advertising NFTs and other blockchain products are becoming common sights. The Staples Center in Los Angeles recently changed its name to Crypto.com Arena. A Bored Ape–themed restaurant is reportedly set to open soon in Long Beach. Cryptocurrency’s presence in Miami is so palpable that one local observer has claimed that “crypto is the new cocaine.”

Cryptocurrency’s ability to alter physical space ostensibly serves as evidence that it’s not just a libertarian fever dream or a hollow grift

For a technological phenomenon that many still dismiss as a stubborn internet fad, this growing offline visibility is significant. As NFTs and other crypto-associated objects assume tangible forms beyond screens and digital wallets, they seem to announce its expanding presence in everyday life, thereby abetting supporters’ claims of its substantiality and durability as a technology. Just as banks once sought to convey a sense of permanence (and thus trustworthiness) by housing themselves in ersatz Greek temple architecture, cryptocurrency seeks to monumentalize itself with its own artifacts. The appearance of Bored Apes and other NFT imagery in public space, as well as bombastic industry events that seem to temporarily take over cities, help create the impression of its world-changing, culture-disrupting potential, the physical counterparts to the popular crypto mantra “wagmi” (“we’re all gonna make it”). The chrome, laser-eyed version of the Wall Street bull statue unveiled at Miami’s recent Bitcoin conference may offer the most explicit expression of this yet. Cryptocurrency’s ability to affect or alter physical space serves as an index of its own ontological autonomy: evidence that it’s not just a libertarian fever dream or a hollow grift but a material culture.

By assuming the mantle of “Web3,” NFTs and other blockchain applications have sought to solidify their path to plausibility and wider acceptance. The name itself, with its presumptuous “3,” implies that it is the inevitable next step in a linear forward progression. Although cryptocurrencies and their associated projects seem to depend upon relentless hype to maintain and increase their value, they simultaneously present themselves as a radical break from the platforms they use to generate that hype. Meanwhile, Twitter’s efforts to incorporate crypto-friendly features like NFT profile pictures into its platform hardly suggest that the company views the technology as an existential threat. But many crypto supporters still claim it represents a revolt against social media platforms’ flaws: their advertising-dependent business models, their algorithmic manipulation of information, and their structural bias toward content that maximizes engagement, which increasingly reorients the world to their incentives.

This “Web3” reframing — to the degree that it succeeds — eliminates the burden of demonstrating that NFTs are “real” assets or that the technology matters beyond its own community of enthusiasts; instead, “Web3” simply needs to distinguish itself from the “Web 2.0” status quo, in terms of its cultural impact, to make its evolutionary self-image seem justified. Then, the decline of any social media trope could be understood as a victory for crypto culture.

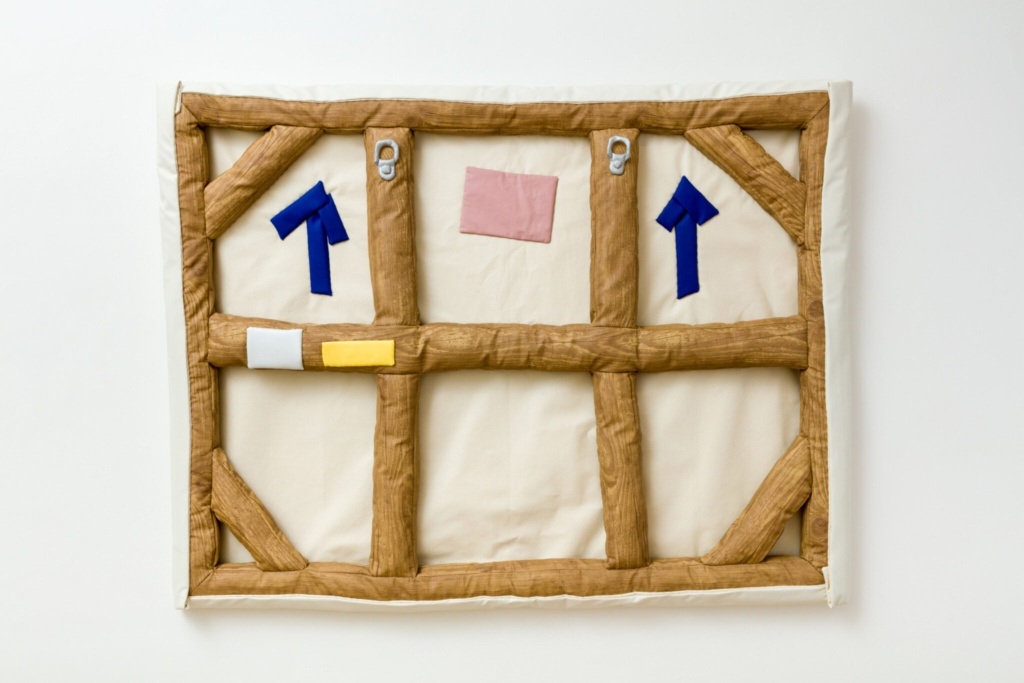

During the past decade, social media platforms have come to shape the urban environment in increasingly visible ways. Previously, trends originated outside the internet’s scope, according to the expectations and opportunities presented by physical environments and encounters, neighborhoods, or in-person meeting places — bubbling up from the proverbial (or literal) streets and only then amplified by social media. Now, trends are formed from the start by what works on and for online platforms, and the design of physical spaces adapts to accommodate them. During the past decade, Instagram-friendly photo backdrops ranging from selfie walls to public sculptures and art installations became familiar sights in cities. A minimalist legibility spread through retail stores and restaurants, even influencing the appearance of the food served.

Instagram’s effectiveness as a marketing channel, in other words, has encouraged businesses and products to become more “Instagrammable,” which Molly Fischer characterized as “a term that does not mean ‘beautiful’ or even quite ‘photogenic’” but “something more like ‘readable.’ The viewer could scroll past an image and still grasp its meaning, e.g., ‘I saw fireworks,’ ‘I am on vacation,’ or ‘I have friends.’” This aesthetic, Fischer argues, “flows freely between physical space and flat image.” In 2016, Kyle Chayka described something similar with “AirSpace,” a globally consistent “faux-artisanal” aesthetic produced by social media’s “harmonization of tastes.” More recently, the newsletter Blackbird Spyplane connected the same sort of style to values like efficiency and “frictionlessness,” as expressed by the sterile minimalism of fast casual restaurants.

There’s a crypto-themed art gallery here. #Bitcoin2022 pic.twitter.com/aGm3r09GLJ

— Ryan Broderick (@broderick) April 7, 2022

If, as many Web3 boosters believe, social media platforms erased the distinction between physical and digital reality the wrong way, infecting the world with the toxic logic of their affordances, then blockchain applications and cryptocurrencies will supposedly mold the world differently, producing a corresponding change in the aesthetic associated with the internet. Blackbird Spyplane’s critique of Instagram-optimized space praises the rise (or return) of the “un-grammable hang zone,” or business establishments that prioritize “vibes” over being photogenic. Wouldn’t “Web3,” in its supposed reversal of “Web 2.0,” produce something like that — a world less tailored to algorithmic virality and performance for the largest possible audience? Wouldn’t one expect NFTs to encourage something that didn’t look like influencer culture, something that wouldn’t need celebrities to pump it up?

One of the most popular arguments in favor of “Web3” is that it gives individuals more direct financial stakes in the projects and communities in which they participate. But this capacity, and the diverse or idiosyncratic developments it may have facilitated, are largely overshadowed by a recognizable visual branding approach, embodied by NFTs, and a multitude of token-investment opportunities that are frequently indistinguishable from scams, gambling, or cynical land grabs. So far, crypto culture’s most familiar aesthetic has assumed the cartoonish form of Bored Apes, pixelated CryptoPunk avatars, and other intentionally low-resolution imagery — which one might interpret as an attempted reversal of polished Instagrammability.

But in practice this aesthetic is more like a new iteration of the same memeability: Cartoon faces travel well on social media and make ideal Twitter avatars for full-time crypto enthusiasts. Not only do they evoke the video game culture that has served as inspiration for many Web3 projects, but they possess the balance of interchangeability and uniqueness that characterizes baseball cards and other collectibles, making them appealing to own but not too precious to ultimately sell. These qualities make NFTs easier to embrace as the tokens they are, along with a visual style that caters to the lowest common denominator, thereby maximizing their potential audience and market (which are effectively the same group). Web3 thus exploits social media to the fullest, using its gamified nature to extract value from users that ad-monetized attention never could, while producing the same aesthetic flattening effect.

Nor is cryptocurrency’s imprint on the cityscape so different from social media’s familiar viral spectacles. Web3’s celebratory climate of surging boosterism in all its forms, rather than the cartoon avatars, may in fact be its version of AirSpace, cluttering the urban landscape with the hype needed to keep token prices inflating: Bored Ape murals look like the NFT version of Instagram-friendly selfie walls. Crypto events and parties frequently ride on the coattails of “Web 2.0” institutions like South by Southwest while depending upon social media’s promotional infrastructure. And the communities that crypto facilitates, ranging from pump-and-dump groupchats to token-based collectives known as decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs), often amount to shared financial interest plus marketing hype, supported by established apps like Discord and Twitter. “Web3” wants its associated culture to legitimize it and distinguish it from “Web 2.0,” but it frequently highlights instead how the differences between the two are often superficial and aesthetic more than they are structural.

Nonetheless, there are deeper differences between business models based on attention alone and those based on asset ownership and speculation. The essence of the “Web3” aesthetic may be this: Web 2.0 in new clothing, exchanging a more straightforward “attention economy” for one that deploys the same virality in order to increase digital asset prices. Doing away with Instagrammable minimalism and replacing it with cartoonish festivity doesn’t mean the underlying infrastructure has changed. It just means social media has a new kind of content.

This content frequently adopts an air of semi-mystery, in contrast to Web 2.0’s cloying straightforwardness, fostering an inclusive exclusivity (“if you know you know”) that presents participants with surmountable, game-like barriers to entry. Web3’s influencers — who obviously still use social media — are more likely to decouple their online identities from their real faces and real names, frequently choosing prized NFTs as avatars and crypto-wallet domain names as their handles, which double as public displays of loyalty to the cause. Web3 also relies heavily on Discord servers and other private chat apps, which contributes to a sense of illegibility, as Venkatesh Rao notes, carving out smaller digital enclaves in which certain types of communication occur. Likewise, DAOs subvert the imperative to constantly maximize one’s online reach, placing users in closer contact with smaller groups.

This “Web3” reframing — to the degree that it succeeds — eliminates the burden of demonstrating that NFTs are “real” assets

In a sense, this furtiveness does reflect the affordances of cryptocurrency and its attempt to convert the attention economy into a digital asset economy. Virality or personal-brand building are not directly rewarded; they are instead mechanisms for inflating the prices of tokens whose value may have little to do with their content as such. The anonymity and illegibility facilitated by private chat apps do complement those efforts, however, by producing FOMO and a sense of insider and outsider statuses, which in turn fuel additional token demand. Despite these qualities, however, Web3 still needs social media, as it ultimately must package itself in an accessible outer layer to attract new participants and new money.

“Web3” promises to remake internet culture as well as culture at large in its own image, just as social media has done. But this doesn’t necessarily mean it solves any of the internet’s problems. In a 2021 essay about the “creator economy” and Web3, I observed that it actually entrenches some of those problems further: “If one of the problems with Web 2.0 was that it demanded constant overproduction, the speculative tendency of NFTs does little to correct that, instead encouraging creators and patrons alike to place more bets.” Or, as Ayesha Siddiqi argued in a recent Substack interview, “The actual legacy of the ‘content creator’ boom is the rise of individual traders on apps like Robinhood, it’s crypto culture and NFTs. It’s asset production in the age of hyper devaluation of labor.” People don’t just want to be Instagram influencers or YouTubers, in other words; now they want to be investors and art collectors too.

Despite its name, “Web3” is less a new “decentralized” infrastructure for disseminating its own trends than yet another trend disseminated by Web 2.0. In that sense, Web3 is fundamentally just Web 2.0 plus crypto. But something is indeed different about it, as revealed by its distinct aesthetic characteristics: It is a medium whose imagery and communication style are optimized to pull people in — to attract their investment and loyalty rather than merely capturing their attention — even as it uses social media’s familiar mechanisms to do so. “Web3” is not the simple envy incited by influencers partying in Tulum but a more intense and complex kind of FOMO, embodied by an ape with a goofy grin.