People who write photo captions for publication will tell you that a caption always has to add something. It should, of course, tell you where and when the photo was taken. It should not repeat what is obvious from the picture alone. The conventional ruling is that a caption — whether accompanying a news photo or your mom’s most recent Facebook post — must not only tell you what you’re looking at, but also why it’s important to look at it. Together, the picture and caption should aim to be more than the sum of their parts.

Photographs have almost always been circumscribed by the language that surrounds them; we crave pictures, but right after we crave words, too. The history and culture of the medium most associated with “reality” is shot through with text that instructs us how to see it. Imagine going to a museum and trying not to read the wall labels — we approach the artwork with purpose, only to be hooked left or right by some invisible force, over to the explanation. We haven’t even looked at the thing yet before we need to understand it. Alone and textless, a photograph could be read in so many (too many) different ways, so a caption strives to pare down the options. This used to mostly happen in a top-down manner: wire services, newspapers, book publishers, galleries, and museums would either write the caption for a circulated photograph, or legitimize it through repetition. Barthes wrote of press-photo captions in particular that “the text loads the image, burdening it with a culture, a moral, an imagination.” He felt the caption was even “parasitic on the image,” sucking out and reducing its possibilities: “By means of an often subtle dispatching, it remote-controls [the viewer] towards a meaning chosen in advance.” A caption not only seeks to explain a picture, it also aims to set it apart and hold it down.

Photographs online are defined not by their singularness, but by their one-among-many-ness, an impression enabled by search algorithms and the design of the infinite scroll

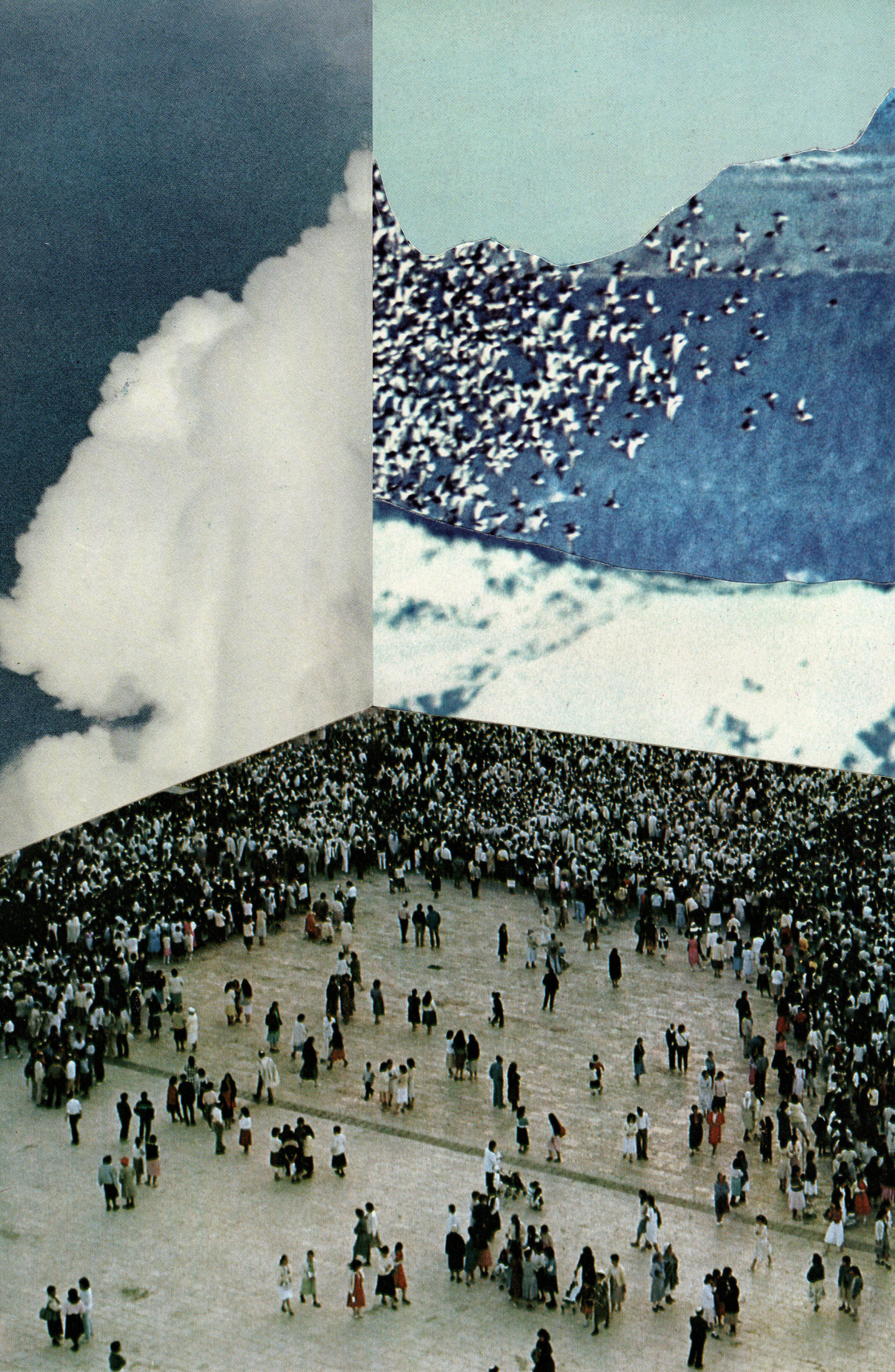

But neat and discrete is not how many of us see photographs now. Forget the money shot, the decisive moment, the photographic hole-in-one; photographs online are defined not by their singularness, but by their one-among-many-ness, an impression enabled by search algorithms and the design technology of the infinite scroll, now a decade old. The scroll’s Escheresque routes keep us running back and around and through, and it makes it feel easy. It’s for looking, for skimming, for light reading and weightless absorption. Language can’t grandstand here; it doesn’t take much before it’s tl;dr. But we can have all the pictures we want, and more. For creatures whose systems and obsessions are usually so shaped by delimitation and naught, we have taken to the scroll — on our apps, our social media, our image searches — and the language it demands with what seems like no effort at all.

It may appear there’s no part in all this for the old model of photo captions. But the information we might have previously slotted into one is just as important as ever — albeit in a mutated form. Traditional captions do still feature on news websites (and their official social-media accounts), but text’s biggest impact on images online is actually in a place where it is felt, not read: as embedded, searchable metadata that determines where and why you see images. An online photograph’s most powerful “caption” is now, in fact, embedded within, in the form of keywords that make otherwise computer-illegible images show up in the “right” places — or, in the language of search, the most “relevant” ones. (On Instagram or Tumblr, the hashtags and geotags people post with their images are another form of metadata that do the same thing.) By ordering and optimizing the world, metadata might make a more insidious claim on objectivity than the pedantic traditional caption: Instead of telling you how to think about the image you’re already looking at, metadata — and the algorithms it speaks to — are more likely to determine what you don’t see at all.

The most defining characteristic of infinite scroll is its illusion of limitlessness. For that, it needs opacity: Anything that could cause friction has to be tucked away or sidelined. That’s why embedded metadata and quick hashtags work so much better than visible who-what-where captions do. Metadata nudges from behind, finessing photographs’ position in searches and the stream. Instead of seeing a photo, then figuring out what it’s “of,” you ask for what it’s of and then you see the photo.

Image search attempts to intuit what a searcher is looking for and show them only that. In this way, metadata’s interaction with algorithms is a distant cousin of the interaction between librarians and the Dewey decimal system. And like Dewey — or other systems of categorization, such as the U.S. census — it adopts a just-the-facts pose. But these are systems created by humans with doggedly limited scope. The census attempts to pin down what kinds of people are in the United States, and it leans on made-up categories to do that; the list of ethnic groups who were at some point not considered “white” in America includes the Germans and Irish, and “Hispanics” weren’t considered a separate category until 1970. Similarly, Melvil Dewey was a sexually harassing bigot and outspoken anti-Semite whose classification system reflected his views. Progressive librarians continue to push back against and revise his system, which, too, has been reformed, in 23 separate editions thus far. Sometimes librarians still have to take matters into their own hands when their institutions fall behind: in 2015, the LA Public Library announced it would finally be moving LGBT-related books from the Dewey-determined section devoted to “abnormal sexual relations” to a less hateful, more relevant classification.

Unlike those two systems, though, metadata is unruly — a so-called folksonomy that thrives on, and constantly reorders, what author David Weinberger calls “the miscellaneous” — and it is not determined by committee, even if the algorithm it speaks to is. Google’s code, like so many others, is written primarily by white and Asian men; as author and former programmer Ellen Ullen has written, “The internet does not filter out social biases; far from it. The internet is an amplifier.” Those who determine the algorithm of Google image search are, maybe, concerned about that. But that doesn’t mean the millions of people who tag their images with metadata are. They don’t have to be accountable to anyone. They have no reason to be progressive in their aims or challenge hierarchies or even tell the truth. They just want to get their shit seen.

In her 2009 essay “In Defense of the Poor Image,” Hito Steyerl writes that poor images — those which have been drafted into a second, lower-res life online — “are poor because they are heavily compressed and travel quickly. They lose matter and gain speed.” The poor images, she writes, are super modular, extremely moveable and easy to put to use for a variety of causes. And although Steyerl is mostly talking about cinema, still photographs work this way online too. Even “official” news photographs, though neatly captioned in their original articles, are still easily drafted into photo streams, memes, and seemingly unrelated image searches.

An online photograph’s most powerful “caption” is now embedded within, in the form of keywords that make otherwise computer-illegible images show up in the “right” places

Internet aesthetics privilege this slipperiness; attempting to nail down a photograph online with a standard interpretation — especially when it’s of a news event or public figure — is just about impossible. Barthes called the photo caption “anchorage”; by contrast, metadata might seem to alternately reinforce and reshuffle. The poor image, Steyerl writes, “floats on the surface of temporary and dubious data pools.” Content is underlined, is undermined, and is often begat by other content. Scrolling through an endlessly replenishing image search or Instagram feed, understanding accrues not through close reading of any one photograph, but through looking and looking and looking; images might seem to be most importantly annotated by the presence of other images.

Try this. Type “three black teenagers” into Google image search. The screen will flood with mug shots. Search “three white teenagers” instead: a milquetoast parade of sweetly smiling stock images. That difference — exemplified famously last year by an American teenager tweeting a video of his searches — comes courtesy of the contexts in which those images were found, as well as the metadata tagged on by civilians. The Google algorithm wasn’t written so it would turn out those results, but it was written in such a way that it could. After the story blew up online and screenshots of the search results were published all over, the results actually started to change: “three black teenagers” began to turn up photos of “three white teenagers,” and vice versa, as well as composite images of the two results side by side. Google’s algorithm has no opinion; it just likes what’s popular. Making something popular is what’s hard to control.

Metadata is one way of trying to do that, of course, and the most visible, seemingly most easily user-controlled form is the hashtag — a form that has proven to be especially anarchic whenever states and corporations have tried to turn it to their ends. Three years ago, the NYPD tried to improve its own image with an internet call-out for positive images of police; naively, it asked social-media denizens to tag their own images #myNYPD. Twitter users immediately put that idea in a chokehold, posting photographs of police brutality instead and tagging them with the promotional hashtag. “Free Massages from the #NYPD. What does YOUR Police Department offer? #myNYPD,” quipped Occupy Wall Street’s Twitter, with a photo of three white cops throwing cuffs on a young black man, his hands behind his back, his face crammed against the hood of a car.

The NYPD fundamentally misunderstood why and how people use hashtags — or even why people caption on social media at all. If the traditional photo caption tells you both what a picture is of and why it matters, the words we add to our own social-media images often skip the “what” and get straight to the “why” — the answer to which is tapped out in a grammar that you really do just have to get. On Instagram we post memes that go in and out with rapid-fire changes of collective mood, or our own photos, accompanied by either no caption at all or the meagerest scraps (THIS, #mood, it me), which then cycle through our feeds in shifting, repetitive constellations — barely-there linguistic complements that might make you laugh but won’t slow your roll. These internet-specific captions are deployed over and over by so many people that they become more like the matting on a frame, presenting a picture and en-specialing it with a joke. As with any riff, there is room for variation; you’ve gotta get the pacing down. I’ve searched high and low for the exact meme that my sister made me laugh with after a breakup (skeleton reclining in chair with the words “My ex waiting for someone better than me”), but I could only find somehow-less-funny versions of the same thing. (Picture of skeleton collapsed over iPhone: “Me waiting for a meme better than that one.”) Memes and memey captions totally change the read of unremarkable pictures. With the who-what-where outsourced on social media to geotags and usernames (if that info is even considered important at all), these captions have all the “usefulness” of a human appendix. But, you know, a funny one.

As Steyerl writes, the poor image defies intentional implementation; it is equally as likely to aid in the capitalist project as it is to lend currency to progressive and radical movements. (Or, we could add, provide the canvas for a particularly savage meme.) Metadata undergirds images online, intending to shoot them to the top of the search — but sometimes, instead, they just slip, slip, slip-slide away.

Metadata’s gestures toward objectivity and the folksonomic bewilderment that ensues are alternately disturbing, frustrating, and useful. But the results can also be beautiful. A few years ago, Frank Traynor of itinerant New York shop/art project the Perfect Nothing Catalog took advantage of Google image search’s unintentional aesthetics by commissioning search terms from artist friends — “sponges,” “world’s most colorful bird,” “bobcat on cactus” — and printing them on clothing using the pattern-your-own-garment service Print All Over Me. Let the algorithm style the body.

Visual literacy is a skill we take for granted, not one usually intentionally taught; but it is also what makes online existence navigable

Similarly, designer Karolis Kosas used Google image search to generate rudimentary art books under the name Anonymous Press: Enter any term on the Press website, and the eight most “relevant” results would be slotted into a generic art-book layout. This would then be added to Anonymous Press’s online library, available to be printed and shipped on demand. Anonymous Press has gone dormant, but not before facilitating such modern classics such as Exploding Eyes and Phallic Vegetables. And while the only words in every book tend to be those of the search term on the cover, Kosas stresses that Anonymous Press is primarily a language-driven project. “Having little control over the visual side of the publication, the users are forced to utilize language as their only design tool,” he writes. “The process thus moves into the realm of literature, where a narrator tells a story and leaves its visual representation to evolve independently in the imagination of his reader.”

The photographer John Gossage is skeptical of intentional photo-sequencing, of the desire to find the kind of meaning that might be expressed in words. “To connect photographs as some sort of narrative is simply conceit of both the photographer and the viewer,” he writes in the text that accompanies his 2011 photobook The Absolute Truth. “All I can say about these particular photographs is that they are certainly previous and elsewhere.” Photographs naturally resist the kind of “anchorage” a traditional caption provides, and that is ever more so on digital platforms populated with more images every day than many pre-internet humans would have seen in their entire lifetimes. Visual literacy is a skill we take for granted, not one usually intentionally taught; but it is also what makes online existence navigable, despite competing priorities and photographic noise.

On the heels of the news caption, the museum label, and the annotated slideshow, metadata represents the latest attempt to marry legible images to text and screw it all down with some sort of fixity of interpretation. But even when your search results are “relevant,” are they what you were hoping for? As the algorithm adjusts under the mass of your emails and calendar entries and late-night window-shopping and the fact that you just read this essay, does it become any better at showing you what you need? If you’re still searching now, do you think you’ll know it when you see it? Language, which Barthes described in relationship to photography as “a kind of vice which holds the connoted meanings from proliferating,” online acts instead as a kind of darkroom solvent: it brightens, disperses, and forever un-fixes.