On the arc of the shift to the small, one could plot many points: In 1665, Robert Hooke published Micrographia, the first great work of microscopy. In 1839 the Royal Microscopical Society was founded. Georg Cantor’s set theory — his finding the infinite in the space between one and zero — went to press in 1874. The electron was discovered in 1897; Bohr’s planetary model was presented in 1913; the onset of the Atomic Age began in the 1930s. Claude Shannon’s dissertation and his theory of “bits” in 1948; the invention of the microchip in 1958; The Blue Marble in 1972. The internet: 1969; the outbreak of social media: the early 2000s.

In his 1985 essay “To Shrink,” philosopher Vilém Flusser attributes the interest in the discovery of worlds within the infinitesimal to a kind of revulsion for the body, a contempt for physical size that, he argues, “represents a regression, a distancing.” It was a sign of how we were becoming “less solid,” diminishing the importance of the corporeal “to the level of a toy” and turning toward “calculation and computation of minutiae to produce information.” In his view, this anticipated a disembodied future in which we’re divorced from flesh and earth, with humans isolated in cells, Matrix-like, communicating as a superorganism — “a unique sort of ant colony.”

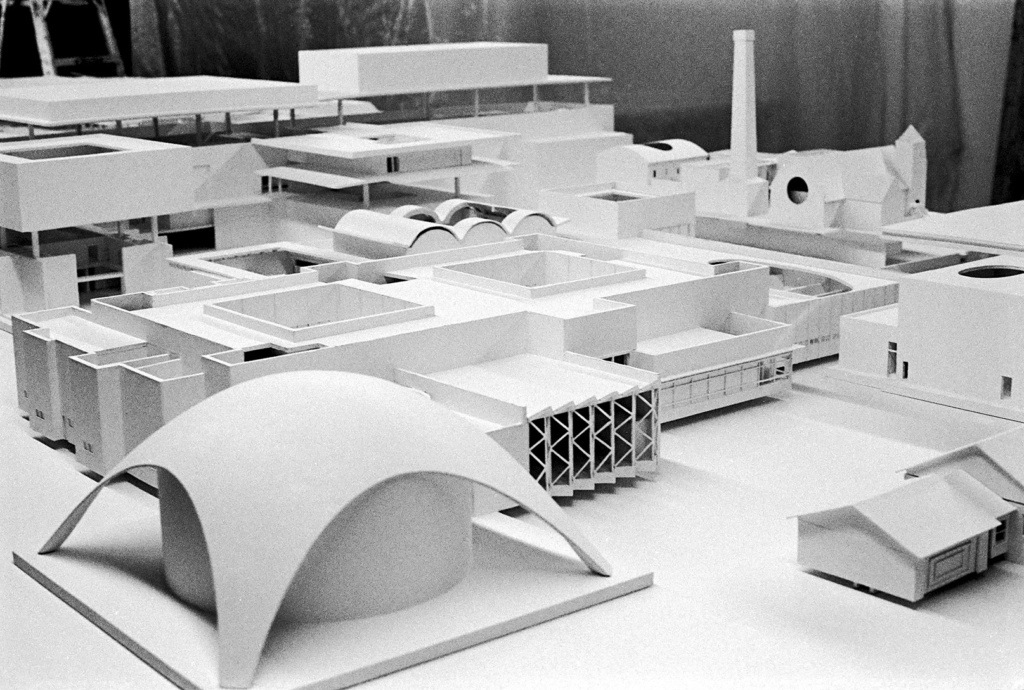

God games invite us to peer at human society like it is an ant farm

While we might not be at that point yet, many of us do indeed play with toy versions of ourselves in toy versions of reality — engrossing miniature worlds in games like Civilization and SimCity and all the other “god games” that have come in their wake. They are miniaturized simulations of life — constructor sets, with players given tools to create, destroy, and manipulate an alternate world history, a model of a city, or tiny families in tiny houses.

There’s something bewitching about this reality compression: a taste of power and omniscience interlaced with the lack of stakes. As a teenager, I would play Civilization, SimCity, and The Sims to cope with a dawning feeling of disempowerment. I spent so much time with The Sims, often late into the night, that I dreamed Pleasantview’s micro-citizens swarmed from my laptop like an angry ant colony to take revenge on me, their ruler, for being so cavalier with their lives. Lately I’ve been taken with mobile games like Rise of Cultures, a Civilization rip-off wherein I instruct pocket-size workers and warriors to farm and fight to grow my empire, or RollerCoaster Tycoon, a shrunken version of the 1999 original, in which I manage my tiny theme park. When I’m not busy redesigning tracks or hiring new janitors, I particularly enjoy watching the teeny people ride the little rides, over and over again, never getting off.

It’s not just about the experience of control, though. The minuscule provokes both awe for its mechanisms — the technical means by which it was brought into existence; the details of its structure — and the distortion of time. In On Longing, Susan Stewart argues that the miniature is a space unattached to “lived historical time”: diminution contorts perception of the world outside, invoking “reverie,” deferring sociality. This leads to what Stewart calls “private time” — in essence an exaggerated interiority. When submerged in a miniature, it is difficult to see outside the frame.

Likewise, players lose hours inside god games. They are sometimes referred to as “time-sweep” games and noted for their addictiveness. Crucially, time moves faster in the god games. Years pass with one turn of Civilization or SimCity. One Sims day is equal to 24 minutes in our world. There is also a particular kind of time-abolishing focus required in making the decisions the games ask, a sense of needing to tend to them. Becoming a god in these games makes itself felt as the assumption of responsibility: The empire will not progress without my oversight. My rides get rusty if I don’t check in on my park. The roads in my city clog with traffic, its citizens complain of stagnation and move out if I don’t make enough metal in my factories to upgrade their buildings. I forget about myself when fixated on my Sims’ report cards, their love lives, their aspirations and hygiene.

In this reality compression, there’s a taste of power and omniscience interlaced with the lack of stakes

It was my mistake to gift my Sim family a remote control car — now Lazlo won’t stop playing with it, he’s glued to the doorway, he won’t quit even though his stomach is empty and his bladder full. And here comes the whole family, worrying about Lazlo’s plunging stats, waving desperately at me because now they all have to use the bathroom too but refuse to enter any door but the one Lazlo’s stuck in, and within a few minutes all their lives are ruined. Thankfully, I can exit the game without saving, revert to a time before Lazlo’s paralysis. But unlike Alice out of her rabbit hole or Rick and Morty from the Miniverse, when I emerge, time has indeed marched by, and I have not tended to anything real.

God games — made specifically to be abstract, simplified, and ambiguous — invite this sort of loss as a kind of mastery. In his 2020 memoir, Civilization creator Sid Meier wrote that in god games, the objective is not to win a final battle with the big boss, as in many other video games, but to achieve “dominance over one’s own limitations.” For Meier, and for Sims creator Will Wright, decision-making is the game: making these choices doesn’t serve to resolve anything but to perpetuate further decision-making. Not only do the choices determine the course of the game; they are held to reveal the player’s real-life character. When playing a god game, you don’t just play the game, you play yourself.

Artist Mike Kelley — whose work in miniaturist mode, like Educational Complex and Kandors, deals with cultural memory and the critique of technological utopias — suggested that “the viewer gets lost in [miniature] objects, and that in the process of projecting mental scenarios onto them they lose sense of themselves physically.” This disorienting disembodiment might account for god games’ lost-time effect, their inducement of compulsiveness. By entering that “private time,” a player is “disarticulated from embodiment and relegated to pure, interior essence” games scholar Gerald Voorhees argues in “I Play Therefore I Am.” As the game inflates you to ersatz divinity, you simultaneously lose time and lose your body — you shrink.

Miniature worlds “are dominated worlds,” Gaston Bachelard writes in The Poetics of Space (1958). He describes the view from the top of a tower and watching other people run around looking “the size of flies,” moving about “irrationally ‘like ants.’” The comparisons to insects, he says, are “so hackneyed that one no longer dares to use them.” But the frequent impulse to see ants like humans and humans like ants has been consistent in moral, fable, and metaphor throughout history. Even though it ignores an infinity of nuance and complexity and often tacitly excuses treating living beings as cogs in a machine whose greater purpose is discernible only to those whose perspective purports to somehow transcend that of both mere ants and humans, the analogy remains unavoidable.

Bachelard’s description is not dissimilar to Will Wright’s Sims vision: He imagined it as a “human flocking simulator,” initially designed with a level of abstraction akin to the view from atop Bachelard’s tower. Wright has repeatedly and avidly cited E.O. Wilson’s studies of social insects as inspiration, telling the New Yorker in 2010 that The Sims drew on his earlier simulations of ant behavior. This means that the people in Sims games aren’t coded with human needs and desires; they are more like ants in human disguises. Playing The Sims is like playing with a kind of hybrid ant-farm dollhouse.

Ants, with their pheromone language, their intricate structures, their farming of fungi, their tendency to ostracize and go to war, are like humans. Rather, since ants came first, humans are like ants. But most important, ants are efficient. They appear to share information in an optimal manner, primarily in their ability to create and follow trails leading to resources, navigate and problem-solve collectively, build tunnels, and keep themselves clean.

This efficiency, as much as their miniature scale, makes insect societies fascinating. Their systems are seen to be more perfect than ours. Ant operations have been used as models for optimization in information and communication science (most commonly with techniques called ant colony optimization algorithms, or ACOs, introduced in AI researcher Marco Dorigo’s 1992 thesis on reduction of airborne pollution in cities). ACOs are a form of meta-heuristic swarm intelligence — collective, decentralized behavior also seen in bees and birds — implemented in phone networks, traffic control, data mining, coal mining, and detection in mine fields. The simulation of ant processes — or the idea that, for instance, ant cleanliness could be applied to nanotechnology — suggests the idea that systemization and computerization are natural phenomena, an elemental, organic form of domination. Because we can find algorithms in the universe, because everything can be broken down into bits, our technology is simply a matter-of-course pathway — linear, like the technology tree in Civilization. It suggests too that hard work can be found in nature: If ants labor tirelessly, mindlessly, then why wouldn’t human workers do the same, under capitalist systems that can be explained as a logical extrapolation from those “natural” ant societies? Labor like the ant and you shall prosper has been folk wisdom since Aesop. (Although recent research shows that the key to ants’ tunnel-building proficiency is actually a lion’s share of idleness.)

God games invite us to peer at human society like it is an ant farm. In playing god games, we replay the systems that have failed us, in shrunken-down, simplified form. The repetition of these systems at miniature scale sustains the notion that they are natural, the infinite complexity and incalculable possibility that characterizes human society overpowered by the fantasy of a basic and knowable human order — a fantasy we play.

It’s not that humans have nothing in common with ants. The problem lies in the idea that ants have a “civilization” that simulates and clarifies how human society operates. This view, exemplified by god games, reinforces the notion of a genetic, predestined order and implies that humans across history are all the same, motivated by the same sets of underlying functions that are more or less obscured or distorted by how society is arranged. A player of these games taps into this fiction of a fated order, even as the game semaphores that we are merely ant-size beyond it.

“It would not be good news to learn that we are all roped together intellectually, droning away at some featureless, genetically driven collective work, building something so immense that we can never see the outlines,” biologist Lewis Thomas writes in The Lives of a Cell (1974). Humans understandably prefer to believe in their own agency, even if it were fictional, even if our ends are not what we think. Unlike ants — as far as we know — we are compelled by a sense of independent purpose. What makes humans singular in their self-consciousness is that everything that confronts them feels like a choice to make and these choices determine the outcome of their lives. The ancient Gnostics believed the ability to choose was proof of an error in humanity’s creation. Perhaps it would be less agonizing to be an ant, or a Sim. As historian Charlotte Sleigh wrote in 2001, “we remain torn between admiration for [ants’] ways and an anxiety that their lack of individuality parodies our own helplessness in society.”

In playing god games, we look at ourselves reductively and carelessly — shrinking, regressing, and toy-ifying life

Our relation to god games is like this: straddling between the wonderment of the small that makes us feel powerful and the knowledge that we do not (and might not want to) wield that power in the world outside the frame. The image of a bored suburban kid with a magnifying glass comes to mind, capriciously tormenting the creatures on whom they can too readily project their own conditioned existence. Studies of Sims play report the re-creation of players’ own families, both positive and sadistic, like turning yourself into an ant to burn — or turning the magnifying glass around to burn yourself. What if life was like this, instead?

Yet the way ant colonies have been idealized and used as a trope oversimplifies entomological reality as much as it does human society. There are more than 12,000 species of ants, most of them hardly studied; we are only one species of the 500 or so primates. Of the ant species that have been studied, there is an overwhelming multiplicity. Army ants build bridges. Leaf-cutter ants not only developed farming; they also evolved to be coated in armor made of rock. Microfossils have been discovered in harvester ants’ intricate refuse piles. Black garden ant queens perform “undertaking” to prevent disease. Acacia ants protect acacia trees; Matabele ants carry their injured kin home. Ant roles are not as fixed as Wilson thought. Indian jumping ants may overthrow their queen and compete for the role — the victor shrinking its brain to save energy for the ovaries, able to regrow it if necessary. Ants might be more conscious than originally believed, meaning the prevailing view of a single ant as a smooth-brained automaton working in service to its queen and their superorganism could be false. A recent book of ant portraits called Ants: Workers of the World highlights their anatomical diversity. Even at this level of detail, Brooke Jarvis notes, the ants “quickly begin to feel not just like individuals, but like people.”

While looking at the “troublesome” yet beautiful minute bodies of ants, 17th century scientist Robert Hooke imagined a perfect glass with which to see at once all the operations of the “Shop of Nature,” transported into the heavens and remaining on the earth, in the flesh, both dominating the world and remaining of it. He claimed that conquering minuscule worlds would lead to mastery in the realm of the human brain. That fantasy lives on in god games, conflating the possibility of deeper understanding with the feeling of god-like will, as if these were the same experience.

In an interview between Wright and Wilson, they agree that games are the future of education. But what do god games really teach us? Certainly nothing useful about the realities of urban planning, or the gradations of cultural and technological histories, or communication between actual humans. Very little about ants. If a player gets time-sucked by the game, there’s certainly less time to actually put feet to pavement, look someone in the eye, feel the endless heatwave. Wilson wrote that we are “terribly confused by the mere fact of our existence,” and god games appear to mitigate that. But we do play against ourselves during that “private time” of reverie, rezoning, waging war, building dangerous rides, getting people fired from jobs at whim like impetuous demiurges, learning not how life works but how decision-making itself becomes escapism. In playing god games, we look at ourselves as reductively and carelessly as we often do ants — shrinking, regressing, and toy-ifying life.

A study published this year suggests ants’ sociality will help protect them from climate change. That doesn’t seem likely for us: You could say we’re in something akin to an ant mill, more colloquially called a “death spiral,” a phenomenon that occurs when one army ant experiences an informational error. Off the scent and confused, the ant follows its own rear and leads its platoon into a feedback loop, resulting in exhaustion or starvation for the whole group. Approaching the end, our character-revealing decisions have compounded; someone is stuck in the doorway. Why not begin the game again?