When it comes to games that simulate the experience of war, it would be natural to think of the realistically rendered battle scenarios of video games like Call of Duty, or battle royale contests like Fortnite, or even the movie War Games, in which a computer AI threatened to end the world by playing out a simulation of Global Thermonuclear War. But there is deeper history to simulating war, not just with computers but with board games — a tradition that goes back centuries, if not to the beginning of history itself.

In different ways, classic games like chess and Go deal obliquely or abstractly with war, instilling lessons in strategic thought and tactical control of territory. But military strategists have long sought something more concrete: games that could model the actual experience of being in a war. One such example is Georg von Reiswitz’s kriegsspiel, or war game, which he demonstrated to the Prussian chief of staff Karl von Müffling in 1824. Like tabletop war games today, it used a topographical map of actual terrain and stylized blocks to signify troops, whose rules for movement were meant to correspond to how troops actually operate.

What made tabletop war games pedagogically useful was not their predictive capabilities for real war scenarios but their ability to teach players how to strategize under a fixed set of rules

Reiswitz’s kriegsspiel was eventually distributed throughout the Prussian Army, revolutionizing not only the training of soldiers but also the logistical and administrative composition of 19th century Prussia, changing how war itself would be conducted to conform more closely to the game. As Phillip von Hilgers notes in War Games: A History of War on Paper, “all the clocks, compasses, scales, and cartographic works” involved in the play of kriegsspiel became “externalized in time tables and codebooks of railroads and telegraphs, thus adapting the battlefields to the conditions of the war game as a medium.” In doing so, the game “reflected very precisely the media that held together the German Empire.” This suggests how simulations don’t merely reproduce what they simulate; they establish a set of abstracted norms that transform the conditions of the original. What is “real” and what is “simulated” begin to become interdependent.

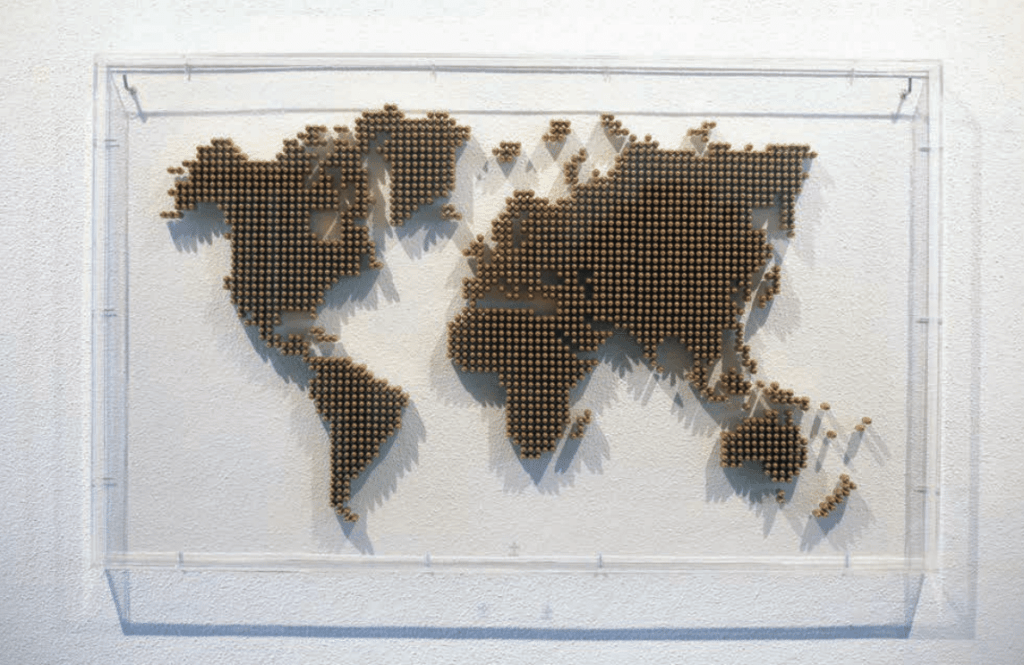

Games and toys, of course, are not politically innocent. In “Puzzling Empire,” literature scholar Megan Norcia describes how during the British Empire, popular puzzles and maps served as “teaching tools through which the meaning of imperial power could be manifest,” instilling nationalist and imperialist sensibilities in children so they might act as rulers or subjects of the imperial enterprise. Children learned to manipulate discrete puzzle pieces in a fashion that mirrored imperial experiences of “discovery,” collection, and administration. Board games have been understood similarly, and not just for their effects on children. They could inculcate a kind of inner emotional logic of power: when and how it could be righteously wielded and how it can be conditioned by the “proper” motives.

Researchers at the Rand Corporation saw tabletop war games in the same way. Rand, which was founded in 1945 at the dawn of the postwar era with sponsorship from the U.S. Air Force, was established to help bridge the gap between military planning and the research and development decisions made by the burgeoning military-industrial complex. It was supposed to develop a “science of war,” and simulations and modeling were key to its mission. Rand employees combined developments in game theory and war-game design to model threats and possible responses in the new atomic age.

But the Cold War threat did not require merely military planning; it also demanded new conceptions of how liberal subjectivity could operate under the conditions of ideological competition (i.e. the persuasive rationale of socialism) and threatened world annihilation. Freedom, in the capitalist world, meant espousing the superiority of self-interest, but fighting Communism required self-sacrifice. To conduct the Cold War required developing new techniques that could help individuals internalize self-sacrifice and order-following without feeling like they were being compelled by an oppressive state apparatus to do so. And whereas the industrial age called for specialization of labor, locking people into specific roles to increase their overall efficiency, the post-war era demanded a populace primed and willing to carry out total war if necessary. This meant developing a flexible citizenry capable of training for and fulfilling strategic and economic needs of the state as they arise.

Rand’s research into war-game simulations was in part aimed at this purpose: to explore liberal subjectivity’s compatibility with modern warfare. In a 1961 paper “The Use of War Games in Command and Control Analysis,” Rand analyst Milton Weiner noted how a war-game simulation “provides a controlled situation for examining the interaction of various decision making levels” brought about through play. The “major promise” of war gaming, he wrote, is that players’ actions “will shed some light on their real world counterparts and thus serve as leads for better understanding and further study.”

But connecting in-game decision-making behavior to potential real-world wartime activity wouldn’t necessarily be a matter of making the simulations more accurate or detailed. What made tabletop war games pedagogically useful, Rand researchers found, was not their predictive capabilities for how real war scenarios might play out but their ability to teach players how to plan strategically under a fixed set of rules. That is, games needed to simulate not wartime incidents themselves but situations that unfolded according to inflexible laws. This, in turn, would shape how actual war conditions themselves would be seen — not as contingent or chaotic but systematic and orderly. In a 1957 memo, Rand researcher R.D. Specht noted that “the value of the game, I think, is not that it predicts the future nor that it allows testing of a war plan. The value of the game … is that the players are taught to consider carefully all their resources.”

Moreover, if games had fixed rules and were amenable to repeat play, the insights of many players could be thereby consolidated and disseminated as general real-world military strategy. As Rand researcher Alexander Mood pointed out in this 1954 paper, “the game pools the knowledge of numerous experts,” transforming their experiences into verifiable techniques “for dealing with problems not otherwise amenable to quantitative analysis.” Regardless of the specific scenario presented, Rand’s war games taught an approach to strategic thinking and assessing the inputs involved in action-reaction cycles that could be seen as dominating all levels of the battlefield. This was helpful in dealing with situations that could not be re-created through live training, such as a nuclear attack, but it also allowed for participants to acquire the flexibility required for dealing with global threats that the U.S. would want to address in the name of fighting for capitalist “freedom.”

Diplomacy involves making and breaking alliances developed in secret negotiations, and players walk away from the game surprised at the level of deceit and ruthlessness players proved capable of

As important as giving strategic insight a coherent form, however, was the emotional lessons a war game could convey. “As a teaching device,” Specht argued, “a war game has unparalleled effectiveness, for the player teaches himself and persuades himself in a manner more convincing than any lecture can possibly be … There is no such thing as vague play in a war game.” But what keeps this play from being “vague” is not the accuracy or fidelity of the military scenario itself but the game’s creation of stakes for decisions. Even an abstract simulation, using cardboard pieces and combat-results tables divorced from the reality of tanks and causality lists, could connect the player to the gravitas of the situation depicted.

Over the course of 1964, Robert Levine exchanged letters with fellow Rand researcher Thomas Schelling — the inventor of deterrence theory — debating the usefulness of simulative crisis games. Levine was firmly against their use, even though he admitted “that games are seductive.” Schelling replied that games are “a social and intellectual occasion” where all sorts of lessons are learned. Players drew real meaning from their play, Schelling claimed, adding that “if one lives through an intense experience he may learn ‘lessons’ … in a way that means something to him in a way that he can talk about with other people who have been through the experience.”

There was no dismissing that fact that simulations produced intense affect. Players walked away feeling that they learned not only something about the situation depicted but also about themselves. They learned about the risk vs. reward calculations they would undertake as military commanders and the factors involved in decisions made by their superiors in military or civil bureaucracies during global crises. They could glimpse not only what was expected emotionally of people in those roles and what purpose they served, but also how they would perform in their place. It prompted reflection on their own sense of subjectivity — that is, the connective tissue of ideological desires, assumptions, and motivations — in ways that reading a book or hearing a lecture typically don’t.

Specht later described the war-game-playing experience as “traumatic” and claimed that trauma served as a useful form of training in itself. “Intensity of communication, rather than correctness of conclusion,” Herman Kahn and Irwin Mann wrote in a 1957 report, “is the hallmark of the pedagogical game.” Play of a simulation often forced participants to adjust their underlying assumptions or worldviews, an alteration of subjectivity that registered for players as trauma. That is why Rand researchers emphasized experience rather than results: Winning mattered less than having the affective experience that signified a successful reshaping of the player’s subjectivity. (This is the same basic premise as the Kobayashi Maru test in Star Trek, in which trainee captains can only fail. Kirk defeats this by changing the underlying rules, undoing precisely the aspect of simulations that Rand researchers found made them useful.)

Anyone who has played Diplomacy, a commercially produced board game about the European balance of power before World War I, will likely have a sense of the sort of “traumatic” affective experience that games can generate. Diplomacy involves making and breaking alliances developed in secret negotiations, and players tend to walk away from the game shocked and surprised at the level of deceit and ruthlessness others and themselves proved capable of. “When people play the game, you get to see their real personality. That’s when they take off the mask,” said Thomas Haver for a 2014 Grantland article about the game. Grantland writer David Hill noted that “the more emotionally traumatic elements of the game are intensified when you’re face-to-face with your opponent.” Edi Birsan, also interviewed for the article, pithily notes that “Diplomacy reflects life.”

The intensity of the emotional experience of play points to how war games construct players’ subjectivity not only within the game or in analogous conflict situations but in general as part of its training function. War games might not directly impart the specific knowledge necessary to be an effective commander or head of state, but it could inculcate players with what Rand researchers believed was the worldview appropriate to leaders.

Analyses of contemporary computerized simulations like flight simulators or networked war games tend to highlight the impact of their realism. In Gameplay Mode, media scholar Patrick Crogan argues that they foster a specific subjectivity suitable to the pursuit of pre-emptive military strategies that blur the lines between war and peace. As the goal of technoculture is no longer to control the future but rather to pre-empt it with the predictive power of simulation, its training games now involve the creation of “just in time” subjectivities — citizens capable of reconfiguring their training and worldview on the fly, allowing, for example, the near-seamless transformation of Xbox or Playstation devotees into drone pilots.

War games might not prepare anyone to be an effective commander or head of state, but it could inculcate players with what Rand researchers believed was the worldview appropriate to leaders

Crogan sees microprocessors as central to creating ever more realistic simulations, which in turn inculcate the “logistical” subjectivity necessary to implement strategies of pre-emption. But what the Rand documents show is that far simpler paper simulations could achieve similar effects by fostering emotional experiences, indelible moments which prompted participants to internalize a worldview far more convincingly than any outside instruction could achieve. This prepared players for the technoculture and its demand for flexibility. But because simulations allow players to internalize those experiences through play rather than through some forcible mode of state indoctrination, they can easily be “ported” into emerging necessities without generating a conflict with the players’ sense of self-direction.

Perhaps the most important consequence of Rand’s experimentation with war games was how it was eventually used to address domestic concerns related to poverty, education, and unrest over Vietnam. By 1966, the Rand board of trustees decided to broaden the foundation’s efforts to include social welfare research as a matter of national security. As David Jardini wrote for the 50th anniversary retrospective in the RAND Review, “the Department of Defense was concerned that the same social ills that provided a breading ground for rebellion in Southeast Asia might also be found in urban America.” As a result, “the sophisticated methodologies developed at RAND to contemplate nuclear war became some of the nation’s fundamental weapons against social injustice.”

When Lyndon Johnson launched the Great Society in 1964, Rand became a conduit through which expertise and methods developed in part through simulations were exchanged between defense and social-welfare establishments. Games about Air Force supply chains or the action-reaction cycle of the battlefield were now applied to urban policy, health care provision, and the unequal distribution of wealth. That means the same subjectivities suited for military preparedness — technocratic solutionist orientations — were being shifted to address domestic concerns, which were seen as “solvable” independent of broader moral and ethical concerns. “Gaming” social problems skirted questions of how society’s rules themselves might need to be changed.

Even today, the legacy and lessons of tabletop simulations can be felt in more modern designs like Hedgemony, a game Rand released this September. The game’s title is a pun on the word hegemony and the importance of hedging strategies. “At its heart, Hedgemony is not a game qua game,” the Player’s Guide notes. “It is a flexible pedagogical tool.” Players can pursue different strategies to try to “game out” possible actions and reactions between geopolitical actors. Yet in pursuing these possibilities — in mapping out the permutations of play — participants learn more than how to build global influence; they learn also what it means to be an ideal subject in the world being modeled. The simulation remakes the player in its own image, instructing them about what their subjectivity must become to be successful in the technocultural era. The centrality of the “hedge” position is another iteration of the demand for a flexible self that nonetheless remains convinced of its stability.

Our present reality is dominated by simulations, and the drive to use technocultural means, like predictive algorithms and artificial intelligence, to anticipate the future rather than react to it. Games are part of the preparation for that world, blurring the experience of simulation and the reality upon which they are based. As Crogan notes (echoing Baudrillard’s argument), simulations open “a passage from the representational logic of the original and its copy to a situation in which the precedence or priority of an original, pre-existent reality is undermined.” As obvious this may be with products like Microsoft’s Flight Simulator or even the U.S. Army’s e-sports efforts on Twitch, Karl von Müffling could recognize it in a 19th century board game. “This is no ordinary game,” he exclaimed after watching two of his officers carry out paper maneuvers and battles as if they were commanding actual troops. “This is a war academy.”