In 1914, Bruno Taut, one of the leading Expressionist architects during the Weimar period, took on the association of German glass industries as a client and designed for them a pineapple-shaped dome structure with 14 sides and a prismatic glass roof like a disco ball. It had floor-to-ceiling colored glass and an interior waterfall between the staircases. This Glass Pavilion, what Taut called his “little temple of beauty,” is widely known as the first significant building that used glass bricks.

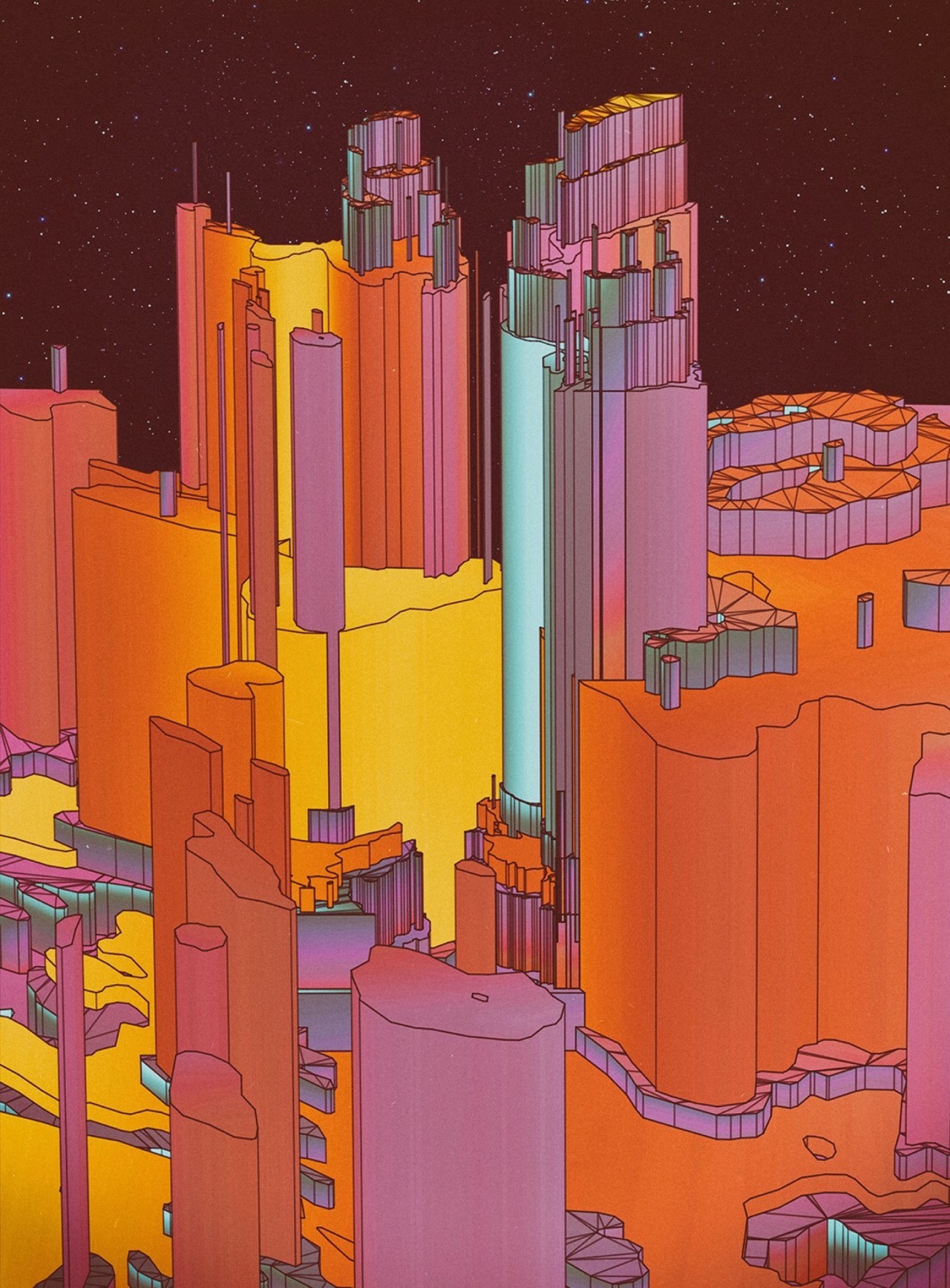

Expressionist artists viewed glass as a symbol of purity and renewal after World War I — Taut described glass in the built form as having a kind of mysticism, a somewhat cosmic significance. “People of Europe!” he wrote in Alpine Architecture, a tome of utopian designs for a city in the Alps. “Create for yourself sacred possessions — build! Be a thought of your star, the Earth, that wants to adorn itself through you!” The modern city in this vision is an augmentation of the earth, building on top of the natural landscape, with and against it at the same time — a form of “augmented” reality that predates the way we understand the term “augmented reality” today.

Taut called on modern society to create a new physical reality, to “adorn” the earth, and enhance it. Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, who was heavily influenced by Taut and is often credited with designing the first glass and steel buildings, imbibed this vision when he stressed on the image of “cut crystal” that would create a kind of jewel-like brilliance on building facades. The glass skyscrapers that dominated the 20th-century city were inspired by expressionist architecture. In cities like New York, the skyscraper would form a large-scale augmentation, an omnipresence, a totalizing landscape — and a precursor to the relatively novel devices that we now use to understand and navigate the city.

The modern city in this vision is a form of “augmented” reality that predates the way we understand the term today

Kevin Lynch, whose 1960 book The Image of the City has influenced urban planning for decades, identified the importance of the city’s “legibility” — “If it is legible,” he wrote, “it can be visually grasped as a related pattern of recognizable symbols.” Lynch argued that an inability to create a familiar image of a city would produce a sense of lostness, and therefore of terror. The urban environment — from streets and buildings to public infrastructure like stations and parks — built amongst, with, and against nature, makes a city make sense the way a book makes sense; a city needs to be “read,” and used. The practice of “sense-making” creates a reality in itself, and therefore a worldview. In this way, legibility is the ultimate form of augmentation, imposed on a city for the sake of enabling, and naturalizing, a set of practices, routines, and values; a grand narrative by which to contain the countless customs and subcultures that make up a city’s life. Inherent to this legibility is curation, and exclusion. Skyscrapers look very different to those who see them largely from the inside, and those who see them entirely from the outside.

“We live for the most part in closed rooms,” Expressionist poet Paul Scheerbart wrote. “These form the environment from which our culture grows. If we want our culture to rise to a higher level, we are obliged to change our architecture.” Scheerbart believed that the imagery created by glass buildings, through their openness to natural light and the environment, would lift society into a higher state of sensory awareness. Ironically, though, now, these same structures typify a distinct closedness. Modern skyscrapers exist, in part, to shield us from the elements while simultaneously controlling them: Buildings made almost entirely of windows that cannot open, and glass that is manufactured for its “sun control” features, its ability to adjust the settings of the natural environment within the built one.

Central air conditioning, which coincided with skyscrapers in early 20th-century America, made it possible to exist primarily within a layer of manmade reality. It radically changed our relationship to the natural environment, which could now be controlled, or obscured, as required. Before central air conditioning was invented, houses were designed in concert with natural airflow: more windows, higher ceilings, porches or water bodies or similar sections of the house that could be spent in the shade during the hottest months. Central AC defined the kinds of structures that could now be built (shopping malls, museums, office blocks) and how people spent the summer (largely at the movies — Hollywood’s golden age began around the same time). Air conditioning, and the general guzzling of electricity, became a status symbol.

Now, buildings are not designed for ventilation — skyscrapers and most office buildings are airtight — but for central cooling. Windows that open ruin the lines of the building as it is meant to look from the outside; they also let in noise and dust, while a controlled environment is cleaner, more stable and predictable — more legible. Willis Carrier, inventor of the modern air-conditioner, marketed it as “manufactured weather.” Architect Rem Koolhaas wrote that “if architecture separates buildings, air conditioning unites them,” and this seems to get at the crux of how the urban environment augments reality: it makes a totalizing whole out of what never was before. The whole city becomes our indoor, customizable, augmented world.

The image reflected on the sides of modern skyscrapers creates a continuity with the sky: look up on a bright, sunny day in New York’s Financial District and you can see the Freedom Tower almost blending in, the blue and white sky running all the way down its side, only brighter. Reflective glass on skyscrapers is not so much mirroring the sky as it is creating a new one that is richer, fuller, responding in real time to the sun and the clouds around it, and which does not dim. This brilliance of light and color gives one the sense of perpetually being awake, or if not awake then on a kind of sleep mode — a state of rest that is only half-restful, ready to spring to a default state of productivity in an instant. It also allows its viewers to enjoy the natural elements — the sun, the clouds, the saturated blue sky — in a unified way, just as Snapchat filters can homogenize our faces. At the same time, the lawlessness, the expressionism, of modifying the given world is what makes these structures so captivating. Modern skyscrapers turn the idea of “natural” architecture on its head: nature is adapting to technology — the sky blends into the building — rather than the other way around.

Taut’s Alpine architecture was meant to challenge and incorporate nature all at once. Taut was not trying to reject nature outright, but his frenetic attempts to conquer it came from a sublime sense of awe. Elements of the modern urban form also inspire this awe: not just at the brilliance of glass, but also its height. Instagram’s #neckxercise hashtag, which has around 5,000 photos on it, is a collection of upward-facing photographs where the jagged edges of buildings jut into the frame like puzzle pieces, all designed to make “looking up” a legitimate aesthetic, lifestyle, and philosophical choice. It is worth remembering that this habit — in very subtle, unconscious ways — validates the many forms in which exclusion is practiced by these structures: reflective glass mystifies the grand activity happening inside the buildings.

Skyscrapers change our relationship to sunlight, to wind and shadow — light inside but no wind; excessive wind outside from all the wind tunnels created by Manhattan’s buildings, and shadows everywhere on the street. We look up and we see these buildings stand in for the stars, the moonlight, the clouds. They make up the urban dweller’s natural environment, their reality: larger and larger spaces whose insides are totally private. The more the urban environment develops and grows, the less our physical, textual, and emotional reality is shared. Hermetic interiors augment the elite experience of belonging inside, while sublime exteriors conduct an atmosphere of submission.

The sky is colonized in physical space by the reach of these buildings, which recognize the sky as real estate. In her book Form Follows Finance: Skyscrapers and Skylines in New York and Chicago, Carol Willis, director of the Skyscraper Museum in New York, talks about the “vernaculars of capitalism” that subtly define the language of the urban form. The location and image of a skyscraper’s presence in a particular place is a product in itself. The architect-designer who developed the reflective glass that came to dominate vernacular office culture in the second half of the century was inspired by a Life ad for mirrored aviator sunglasses.

We are the unconsenting audience of this art form that is our skyline, taking in these images regardless of whether we are looking up to see buildings or clouds

The sky, which one would think is a kind of commons, is also the screen onto which much of the advertising (or potential for advertising) that affect our lives is displayed. American Surety, Singer, the MetLife building, and Banker’s Trust are just some of the skyscrapers that were created solely for the purpose of branding large-scale enterprises. There is a connection between the glamor of corporate spaces and the value that our society places on work; the visual language of skyscrapers represents the dynamics and objectives of capitalism itself. As Marx described capital’s function as squeezing value out of labor until it can no longer produce, skyscrapers, towering into the sky, squeeze space literally out of thin air.

The utopian ideals for Expressionist architecture involved a kind of classless harmony with nature, but in our contemporary society, the structure and placement of skyscrapers reinforces an economic order — these looming constructs impose on and remake the surrounding environment according to a certain logic, augmenting the life of the city. Whether in the form of homogenizing experience through weather control or shielding their occupants from the street and vice versa, or exercising “soft” power by building corporate branding into the physical landscape of a city, they enact and represent the forces of exclusion and economic segregation, literalizing modern capitalism.

In 1936, Harold Ross, while serving as editor of the New Yorker, received an angry letter from New York architect Aymar Embury II, reacting to Lewis Mumford’s curmudgeonly “Skyline” column of architecture criticism. “It does seem very highly desirable to say a kind word once in a while if only for the heightening effect of contrast,” Embury wrote bitterly. “Whenever I read Mumford’s criticisms, I just boil. They are very offensive.”

In defense of Mumford, Ross replied rather acridly the following week: “I sometimes realize that architecture is one of the few subjects I cannot detach myself from emotionally. I don’t have to go to a theatrical production if I don’t want to, or a moving picture, or look at a painting, or, at worst, I can walk away from these things. But a building is there, and I’ve got to look at it, and realization of this sad fact frequently makes me indignant and downright bitter.” Ross’s feelings seem entirely justified in the context of an urban visual landscape that is an open canvas for the increasingly few to express themselves to the increasingly many. We are the unconsenting audience of this art form that is our skyline; we are constantly gazing up at these dominating phallic marvels, taking in these images regardless of whether we are looking up to see buildings or clouds.

The image of the city has a deep, psychological impact on our sense of civic selfhood. In the 1970s, New York’s tourism bureau began to capitalize on the nickname “the Big Apple” and used a campaign to turn it into a brand; Milton Glaser’s “I Love NY” became a design icon. After September 11, one passenger on the Staten Island ferry looked at the skyline and commented that it was like the city had lost its two front teeth. There is an undeniable cultural capital associated with this stylized production of civic pride. TV has always been quick to exploit the image of the skyline for subliminal messaging: quick shots in between scenes establish setting, and some of these are shots so fast we don’t consciously register them. Media creates legibility and familiarity, too, through a kind of narrative augmentation that arguably renders, or attempts to render, physical familiarity almost irrelevant. This is how the city markets itself not just for its residents but for the world.

Today this civic self-branding is inextricably linked to the capitalistic impulses that drive the modern city. While the original Expressionists imagined the city as an “adornment” or augmentation that would manifest utopia, the city now reshapes itself in the image of its wealth. Advertising, especially in public places, appeals to a continuously created sense of civic identity: Casper, Fiverr, and StreetEasy are just some of the omnipresent brands on the subway that, subtly or not, call on the viewer to be a “New Yorker,” promoting the sensibilities that supposedly characterize residents of this city. A recent Seamless ad campaign, showing the “unusual” add-ons demanded of restaurant workers by customers (“Go to 2B. Tell them to stop stealing my wifi. Deliver to 2A for a well-earned high-five”), effectively paints New Yorkers as self-indulgent, unthinking consumers with no interest in treating workers of the service industry with humanity or respect. These ads can seem perversely accurate, mirroring the dynamics of class hierarchy and cruel hypercapitalism that in many ways define the city now.

It’s not just our physical reality that is augmented by the modern urban environment, then, but also our emotional reality, our sense of identity. And city branding translates directly to our own personalized branding. Just as the experiences of the characters in Friends seem that much richer and more vivid when preceded by shots of the New York skyline, so too do our own experiences in documentation. Cities enable aspiration, which in turn enables strong brands. Self-expression that supports the dominant city narrative, one augmenting the other, has massive power.

The signifiers that cities provide make our lives more legible for an audience. They also inspire and imply a cultivated attitude, a level of experience, and a vast and intimate, secret knowledge — a kind of exclusivity and secrecy that the buildings themselves exercise on us. What Adorno and Horkheimer called the “culture industry” is evident here in the way capitalism uses social media culture to redevelop cities into truly contemporary, post-industrial ones. From branded skyscrapers to portable Instagram moods, the city is being commodified in increasingly intangible ways. The images that this culture produces are an augmentation of an augmentation, which have very little to do with the way most people living in New York actually move through the world, but which make strong statements about how we should move through the world, or perform our movement through the world.

The “adornment” that Expressionist thinkers advocated for nature was a response to oppressive aesthetic norms, and it had a distinct artistic and progressive political purpose. These radical goals may be irrelevant in the contemporary urban project, but the importance of individual expression remains in this image-making culture — we, as the recipients of these various modes of expression within the built form, understand the social and cultural value of producing our own versions of these mass images. We, in our investment in not only living in a legible city but also becoming legible to the agenda of the city, are a necessary part of this totalizing vision.

Still, however, the city is the ideal place for creating movement through the world in a way that can defy or escape the contemporary world’s wealth-oriented agenda. The city is the manifestation of capitalism and at the same time, in many ways, the only place where capitalism, and the legibility of corporate functionality, can be escaped. Jane Jacobs’ famous “sidewalk ballet,” where people loiter on stoops for hours without producing anything of value, where they leave their mail and their keys with total strangers at the corner deli, where the exchange of meaningless conversation between a newspaperman and a deli owner and a commuter waiting at the bus stop and a local resident hanging around her window can determine the course of a day, is an omnipresent urban dynamic that is constantly escaping, actively, the project of capitalism. As critics of the Seamless ads have pointed out, we do not, in fact, live in a city where it is possible or even actually cool to totally avoid human contact — we live in a large, dense city that is full of unpredictability. Just as the city is prone to having legibility imposed on it, it is also the space where illegibility is most possible, and has the most potential.