This week I’ve been struggling to get things done. The litany of terrible ideas from the tech world proceeds as usual — for example, these AttentivU glasses that read the wearer’s brainwaves and administer jolts when the EEG reading falls out of the normative “attentive” range — but I don’t seem to have any new or cogent ideas about anything. Instead, I have been spending a lot of time I don’t really have Photoshopping my face into old Stephen Stills album covers. It seems like a perfectly useless task, so naturally I find it easy to concentrate on it. I can spend hours meticulously sculpting pixels and trying to color-correct by trial and error without breaking to check Twitter even once.

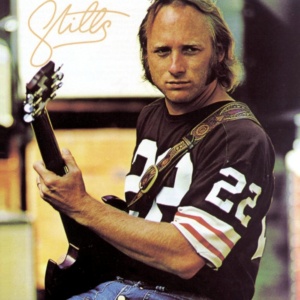

I’m particularly interested in the 1975 album Stills, his first album for Columbia Records, which I have never listened to. But I’ve spent a lot of time looking at the cover. For instance, I think a lot about the football jersey. Why put that on the cover? Maybe Stills is a big fan of the Cleveland Browns, but that seems unlikely, given that he is from Dallas; it seems more probable that, like Mick Jagger, he thought that wearing a jersey from whatever town he was playing in on a given day would help win over the crowd. Perhaps Stills wanted to establish the football-jersey look as part of his brand, to convey the idea that despite being a renowned rock star, he remains a regular-guy sports fan.

It’s also possible that Stills’s proclivity for football jerseys is meant to communicate that he is a good teammate — no one special, egoless, just number 22, chipping in with what he can do on guitar. But this seems especially ludicrous given the contentious history of Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young. The CSNY Wikipedia page is full of stories about their fighting; my favorite has to do with the album Stills and Young recorded together in 1976, Long May You Run. At one point it was meant to be a full CSNY reunion album, but the vocals Crosby and Nash recorded it were subsequently erased when they went off to fulfill contractual obligations to record an album as Crosby Nash. Robert Christgau’s review of Long May You Run captures its ambiance well: “a profit-taking throwaway, but that’s not necessarily a bad thing — Young is always wise to wing it, and the less Stills expresses himself the better.”

Stills and Young then went on tour together to promote the record, which is named for a love song Young wrote about his car. But “after a July 20, 1976, show in Columbia, South Carolina,” the Wikipedia page notes, “Young’s tour bus took a different direction from Stills’. Waiting at their next stop in Atlanta, Stills received a laconic telegram: ‘Dear Stephen, Funny how things that start spontaneously end that way. Eat a peach. Neil.’ ” Long may you run, indeed. Whenever I think about this story, I imagine Stills wandering around a stadium parking lot in a football jersey, looking for Young’s tour bus. I also picture myself showing up for a show at, say, the Lakeland, Florida, Civic Center expecting to see Neil Young but being stuck with just Stills. Gee, I hope he plays “Love the One You’re With.”

Incidentally, Young turned up in last week’s New York Times Magazine, complaining to writer David Samuels about how music optimized for streaming is enfeebling our brains.

We are poisoning ourselves with degraded sound, he believes, the same way that Monsanto is poisoning our food with genetically engineered seeds. The development of our brains is led by our senses; take away too many of the necessary cues, and we are trapped inside a room with no doors or windows. Substituting smoothed-out algorithms for the contingent complexity of biological existence is bad for us, Young thinks.

As sympathetic as I am to that idea that predictive algorithms compress the potentialities of those subjected to them, it still find it a bit arbitrary to hail an analog recording as “human” and a compressed digital one as not. Young’s attitude to sound reminds me of Hito Steyerl’s idea of the “poor image” — how lose quality as they are optimized for circulation in digital networks — but Steyerl takes a more dialectical view: “The circulation of poor images feeds into both capitalist media assembly lines and alternative audiovisual economies. In addition to a lot of confusion and stupefaction, it also possibly creates disruptive movements of thought and affect.”

Much of Samuels’s article is given over to exploring the possibility that certain “real” sounds can fix human brains, while other “degraded” sounds are destroying our abilities to communicate. This seems meant to celebrate the importance of the sonic anomalies and imperfections of analog recording, but it is also implicitly suggests that settling for anything less than the highest fidelity recordings makes a person subhuman.

A better argument, perhaps, against Spotify and all the other streaming services has nothing to do with “sound quality” or “real music” but with how its capacities reshape our aims with regard to music. In Nihilism and Technology, Nolen Gertz argues that “modern technologies appear to function not by helping us achieve our ends but instead by determining ends for us, by providing us with ends that we must help technologies achieve. Thus the Roomba owner must organize their home in accordance with the maneuvering needs of the Roomba, just as the smartphone owner must organize their activities in accordance with the power and data consumption needs of the smartphone.” Something similar happens with respect to Spotify, so that the purpose of engaging with music appears to be to find ways to let it stream.

Gertz argues, via Nietzsche, that we are intrinsically burdened with our subjectivity and seek technological means to escape it, to induce “self-hypnosis” and have decisions made for us. (I think there is nothing intrinsic about this but that it is grounded in material conditions of economic precarity.) This escapist drive “represents a desire to resign from the world, a desire to be free of desire, to live without living.” I get the feeling Neil Young might say that streaming music represents the desire to listen without listening.

But I also get the same feeling from the cover of Stills, which from my vantage point seems to aggressively push its own mediocrity, a sense of settling for lazy choices. It screams “obligatory and forgettable.” I try to imagine how many people were required to sign off on this cover, who looked at this bland image of Stills onstage and decided, Yes, this will sell. This is good enough. Let’s launch his career with Columbia with this motif. I wonder if Stills himself was involved in the decision, if he or anyone was presented with other choices.

The half-assed nature of the packaging is reminiscent of the Camden-label Elvis Presley releases from the late 1960s and 1970s that I’m guessing Elvis didn’t even know existed. These had running times of 20 minutes or so and looked like they took about five minutes to put together. And maybe that was the idea with Stills. Its undercooked, slapdash quality seems almost too blatant, as if it were a deliberate badge of his lofty lack of concern: Stills can’t be bothered to think of a title for this album, so it’s called Stills. Stills doesn’t have time for cover concepts, so it’s a more or less random photo of him in concert. Stills is so massively famous that his record company will put out his albums even when he is trying hard to not try at all, that he has nothing left to say.

I often wish I had this kind of confidence. The best I can do is make amateur efforts to superimpose my face over his and deepfake one of his moments of triumphant indifference. (And write posts like this one when I also have nothing left to say.) It’s like Stills’s relevance to the music industry could be confirmed only by putting out material that deserved no attention on its merit. Anyone can make good music sell, but it takes a special talent to move units of total shit. I read some of the reviews Stills received at his commercial peak: Rolling Stone‘s reviewer called him “a solid second-rate artist who so many lower-middlebrows insist on believing is actually first-rate, even in the presence of overwhelming evidence to the contrary.” Then his lyrics are dismissed as “alternately trivial, cloyingly self-important, and downright offensive … The crucial contemporary issue Stills is most vitally concerned with is himself.”

That sounds a lot like my own interior monologue on those days when I feel like I should try to write things but become embarrassed by the temerity of it. I’d love to blame the algorithms for that feeling, and probably have somewhere. But Stills seems to have been undeterred, existing in the cocoon of his own sense of relevance. Isn’t that what algorithms are supposed to create for us? How many more social media posts do I have to make before I’ll be ready to just post anything? Am I already there?