TikTok, a Vine-like app for making and sharing videos, has recently been getting the app-fad treatment. Real estate writer Sally Kuchar’s sentiment seems typical: “TikTok is so wholesome and wonderful and good. It’s currently my favorite place on the internet.” Or here’s Julia Alexander at the Verge: “I’ve been using TikTok for a few months now, and it’s quickly become the only app that gives me unbridled joy anymore.”

The joy these writers express depends, somewhat vampirically, on the “young creators” that have embraced the platform and whose use of it reads to older writers as authentic, purportedly purified of the toxic motives that pollute more mature platforms. Instead of spewing hate and conspiracy, the youth make earnest, innocent-seeming memes and participate in “charming” “incredibly fun” challenges as a way of asserting membership of an emerging “community.”

This sort of hype — touting TikTok as the savior of social media, an oasis amid the desert of joyless “inauthentic content” — almost demands a debunking backlash. Usually the party ends with monetization efforts — typically that is when a site starts leveraging its data against users to show them ads. And that day is coming soon for TikTok. (Thanks to David Turner for the link.) At that point the charming creators of youthful content become complicit in the platform’s engagement and marketing strategies.

But this Vice piece takes another angle, pointing not to the commercialization of everyday kids’ participatory fun but to the algorithmic processing that TikTok uses to push content:

Like YouTube, TikTok also relies on a recommendation algorithm that has the same problems as any other recommendation algorithm. Namely, we don’t know exactly how it works, and, anecdotally, the algorithm seems to create echo chambers of content that allow users to not only subconsciously construct their own reality, but also can push users toward more radical content.

As this gushy explainer for venture capitalists emphasizes, TikTok (known as Douyin in China) relies even more heavily on algorithmic autoplays: “Unlike most video apps, there is no ‘play’ or ‘pause’ button on Douyin. Once you open the app, a video starts playing immediately. You scroll through a bottomless feed of 15-second videos — just like how you scroll through pictures on Instagram. And because it is mobile only and the content is so bite-sized, people consume it everywhere.” In other words, TikTok takes the logic of default autoplay, which investors and marketers love, and implants it in an environment where users apparently don’t experience it as callous indifference to their preferences. It makes me think of the chair that Malcolm McDowell is strapped to with his eyelids forced open in A Clockwork Orange, only the straps are algorithms and users offer no resistance.

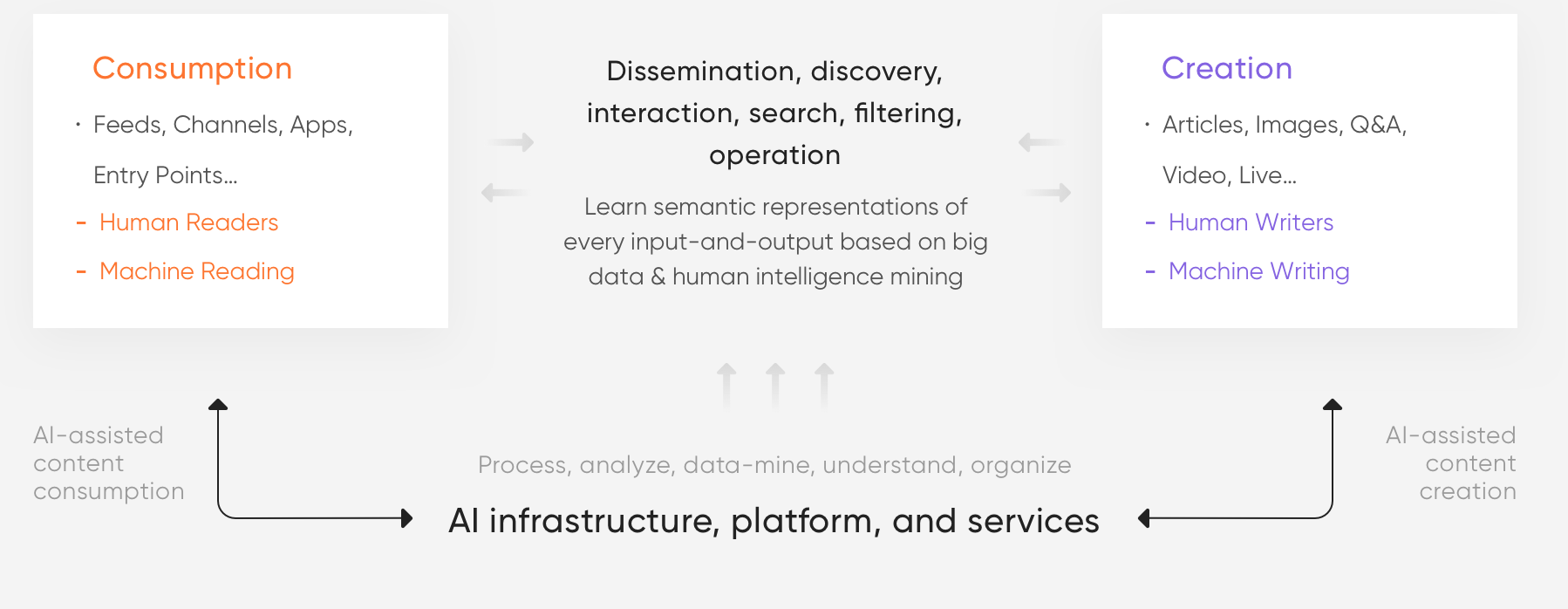

ByteDance, which owns TikTok, represents itself not as a media platform but an AI company. Its main product in its own view is algorithmic personalization, not any particular piece of content or any special ability to keep users authentically “connected” with friends and family. “On any ByteDance content platform, you don’t need to provide any explicit input or your social graph,” the company explains on its site. “The technology embedded in our platforms learn about your interests and preferences through your interactions with the content — your taps, swipes, time spent on each article, time of the day you read, pauses, comments, dislikes, favorites, etc. The result is a personalized, extensive, and high-quality content feed created specifically for you each time you open the apps.” ByteDance is not interested in who you think you are or what you think you want: It instead intends to remake you in the image of what it can deliver. Its data collection and machine learning algorithms, it claims, facilitate a “virtuous cycle” where by “AI-assisted content creation” feeds “AI-assisted content consumption” and vice versa.

In short, the app is designed to eliminate the idea of browsing for content and instead showers content on you in a frictionless flow. You don’t have to follow anybody; you don’t have to search for anything. The app just immediately begins to profile you, automating the process of becoming somebody on the platform. There is no pretense that users have conscious, considered wants that the platform can hear and respond to; it instead presents itself as an assiduous butler who anticipates what one needs and presents it before they thought to ask. But that is really a subtle form of control: give people something to preoccupy them before they think to start asking questions and making demands. Once they are used to being bottle-fed, they might not think to ask for anything other than formula.

The old theories of consumer “prosumption” tended to presume a conscious agency on the part of consumers to “co-create” value through using products. TikTok, like other algorithmic recommendation systems, dispense with the users agency or conscious intent, and turn data and captured behavior into a resource for its decidedly one-sided production of your taste profile. The bet is that people don’t want to co-create identity with consumer choices so much as consume their own identity obliquely as a consumer product. TikTok structures users not as people with agency to express their own tastes, but as people whose tastes are always already expressed as relevant and catered to. Rather than choose something and possibly choose wrong, users are habituated to the experience of not having to choose, as though that exempted them from the status anxiety of using taste to build cultural capital. “AI-assisted content consumption” allows users to enjoy the absence of choice not as deprivation but as convenience. They can experience preemptive personalization as the confirmation of identity rather than the platform’s self-interested imposition of it. The fact that you don’t choose content for yourself doesn’t show your ignorance and absence of taste, but your wisdom in letting AI constitute your taste for you.

Earlier iterations of social media made you work at building out your identity, reproducing it online within their database’s structures — this was the “immaterial labor” of being online during what could be called the formal subsumption of identity creation by social media: The identity work that used to be performed through taste displays and affiliations in “real life” were now being replicated on online platforms, but that work hadn’t yet been reshaped by the platforms’ affordances. They were only starting to function as the means of self-production. Now that the platforms are built out and the “primitive accumulation” of social data is largely complete, and the apparatuses of data capture are functioning more or less automatically, the real subsumption of identity has begun: This kind of identity is articulated within the horizon established by networked social media and is unthinkable outside it. What social media do is integral to selfhood as it is now socially constituted, structuring the desires, tastes, behaviors, and aspirations we might think to have.

In providing the backdrop for selfhood and the grounds for coherent subjectivity, social media have begun to take over the role that conventional consumerism had played for most of the 20th century. They are a continuation of self-production through displays of consumption rather than a repudiation of it: You post yourself doing branded things and having branded experiences — and increasingly you consume content chosen for you that is effectively the spectacle of your earlier behavior translated into consumerist identity: This is what your underlying marketing data looks like, this is how it defines you, this is who you are.

Shoshana Zuboff’s analysis in The Age of Surveillance Capitalism condemns tech companies for its efforts to automate taste, but frames this as a kind of betrayal of consumer identity, which she regards not as a economic distortion of individual desire but a transparent reflection of it. What we want, in her view, essentially transcends the economy, but those integral wants guide companies toward fulfilling us. When tech companies use surveillance to anticipate those consumer desires, they are cheating this process. Accordingly, Zuboff’s book includes lots of charts like ByteDance’s above that depict feedback loops, but she describes these not as “virtuous cycles” but as “behavior modification” that deprives people of their individuality and inculcates them with false, compulsive desires that produce profit for platforms.

But who is to say what someone’s “real tastes” are? It is not as though they can be formed in a vacuum. Why should we accept the tastes formed under consumer capitalism to be legitimate while the ones produced under “surveillance capitalism” to be false? As Evgeny Morozov points out in this review of The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, Zuboff has a longstanding investment in the idea of consumer sovereignty as the expression of personal freedom and self-determination, and the benevolence of “good” capitalism for catering to our true, individuated desires. It offers us variegated products that allow us to express ourselves in unprecedentedly elaborate ways, which means we can be more precise than ever in articulating our true selves. In this, we reap the harvest of modernity, which liberated us from traditional, static identities and saddled us with the existential duty of discovering who we are. It can be hard sometimes, Zuboff concedes — “an extraordinary achievement of the human spirit, even as it can be a life sentence to uncertainty, anxiety, and stress” — but such is the price for the “human future” she rallies readers to defend in her book’s subtitle.

The problem with “surveillance capitalism,” in Zuboff’s view, is that it prevents consumer sovereignty from forcing companies into facilitating this individuality. The kids having fun on TikTok, then, are actually being surreptitiously reprogrammed to a life of false consciousness in which meme-making for corporations is the best way to have a personality and sustain friendships.

I don’t even necessarily disagree with that; in fact, I had been regularly citing Zuboff’s newspaper articles about “surveillance capitalism” because it seemed like a useful way to talk about how companies were reshaping subjectivity through ever more extensive means of monitoring users. But now I feel obliged to throw the term in scare quotes because her book has saddled it with a pro-capitalist theoretical apparatus that is hard to stomach. As Ben Tarnoff noted in this thread, Zuboff argues as though “‘surveillance capitalism’ is a radically worse form of capitalism than the one that preceded it” rather than being an extension of it, and posits the existence of a “Good Capitalism” that supports universal human flourishing rather than continually developing exploitable asymmetries that protect the privilege of the few while pitting everyone else against each other.

Zuboff’s approach assumes that becoming people more and more individualistic is the telos of human existence, and not some form of social justice where life opportunity is more or less equally distributed. The will to individuate is seen as straightforward and unquestionable, as if there weren’t an infinite number of ways to pursue it and to balance it against the forms of social belonging that make it possible. Zuboff writes:

Our expectations of psychological self-determination are the grounds upon which our dreams unfold, so the losses we experience in the slow burn of rising inequality, exclusion, pervasive competition, and degrading stratification are not only economic. They slice us to the quick in dismay and bitterness because we know ourselves to be worthy of individual dignity and the right to a life on our own terms.

That seems an admirable enough sentiment, but the “grounds upon which our dreams unfold” are not separate from the social reality that gives them form even as it limits them. “Psychological self-determination” emerges from social conditions and is oriented by them. Zuboff also doesn’t go on to acknowledge capitalism’s unceasing role in producing that lamentable inequality and stratification. Somehow consumer capitalism, which is largely built on allowing people to express invidious gradations of social class through goods — as Bourdieu argued in Distinction — is, in Zuboff’s view, a liberator and an equalizer. The problem is that consumer capitalism functions not by universalizing the right to self-actualization but by extending that “right to a life on our own terms” unevenly across populations, fostering zero-sum competitions over who gets to be more real or more human than someone else. Struggles over positional goods (like luxury goods and beachfront property, etc.) are characteristic: Only some people can have them and the power that radiates from them, the cultural capital they confer. Everyone else has to be envious on their own terms.

The point is that individualism is defined against the relative conformity of everyone else, the masses who don’t have the resources to be as uniquely tasteful. I was struck recently, while reading a collection of early responses to the Beatles, by conservative commentator Paul Johnson’s unapologetic venom at what he regarded as the “intellectual treachery” of considering the band to be legitimate culture. Pop culture, he complained, “has been smeared with a respectable veneer of academic scholarship, so that now you can overhear grown men, who have been expensively educated, engage in heated argument on the respective techniques of Charlie Parker and Duke Ellington.” That sentence manages to be sexist, racist, and classist all at once, under the governing idea that only “expensively educated” people have the right to genuine individuated taste; everyone else is of course a bunch of tasteless morons. The panoply of Beatles fans “is a collective portrait of a generation enslaved by a commercial machine,” reflective of an “anti-culture” reflective of the decadent “cult of youth.”

I was chastened by this; it resembles my gut reaction to TikTok, and to the other new commercial machines being built out. Do I really want to endorse the idea that only the people with money should be perceived as capable of escaping “enslavement”? But do I want to believe that consumer culture is a useful mode of democratization? It seems like it proposes no escape for anyone.

Even when companies are responsive to consumer whims, that is not because the consumer somehow has the upper hand; it’s because the consumer has already been consigned to seeing themselves only as a consumer — their desires are already contained within a system optimized to profit from selling identity-symbolizing goods. Their identity and subjectivity has been developed within a system that suppresses alternatives and rewards participation in status games, even on the arbitrary and uneven basis it affords most people.

Social media are an extension of the means of structuring identity and subjectivity within that system, where all forms of desire are understood as individual property and not a component of a social field, let alone a potentially collective expression. People need social context to figure out what to become, what a dynamic “real self” might mean; it doesn’t occur in a vacuum. Isolating people as “individuals” as if that were sufficient to dignify them doesn’t fulfill people so much as isolate them from the means of fulfillment.

There is no authentic road of self-discovery that surveillance capitalism can corrupt. If anything, companies like Google and Facebook (and now TikTok) aggressively individuate users under the guise of personalized algorithmic processing. No one can be anything but a unique user ID within a world dominated by surveillance capitalism.

Rather than see individual consumer autonomy as the master goal, might there be something redemptive in the social consumption at work in fads and participatory platforms, where the desires of many are amalgamated and put into motion and can only be accessed or experienced by individuals by becoming part of a mass, by surrendering individuality in the process of consumption? Film critic Andrew Sarris’s response to A Hard Day’s Night hinted at this: The Beatles’ haircuts, he suggested, “serve two functions. They become unique as a group and interchangeable as individuals … And yet each is a distinctly personable individual behind their collective façade of androgynous selflessness — a façade appropriate, incidentally, to the undifferentiated sexuality of their sub-adolescent fans.” The champions of TikTok (and all the other pre-commercial social apps) seem to be getting at this too: a kind of consumption that doesn’t strictly speak to one’s personal identity and which offers no special distinction or cultural capital, just a sense of belonging, a sense of creative momentum, and a pleasure that isn’t zero-sum, of individuality or notoriety necessarily at someone else’s expense. Beatlemania wasn’t a matter of drooling teen morons too dimwitted to be educated into the kind of high culture that has conventionally conferred the individual dignity; it was a mass interrogation of dignity on those terms. Individualism doesn’t need to be a heroic existential struggle against other people. You haven’t lost if you sing along.