In 2011, Saroo Brierley found his way home. Born in the village of Ganesh Talai in central India as Sheru Munshi Khan, he was just five years old in 1986. That was the year he and his brother boarded a train to the city of Burhanpur, 45 miles south of Ganesh Talai, to look for spare change underneath seats. It was their way of helping out their single mother, Fatima, then struggling to make enough money for the family to survive. Brierley fell asleep on a bench at a train station, and when he woke up, he was alone. In a daze, he boarded a train lodged at the station, thinking his brother was on there. But only after the sun came up did he realize he’d boarded a freight train bound for an unknown destination. His brother wasn’t aboard. Brierley ended up in Kolkata, more than 900 miles away, where he made his way to an orphanage. From there, two white Australian nationals adopted him and brought him to Tasmania, and as he grew older, time scrubbed his memory clean of his mother tongue, Hindi, replacing it with English.

As a college student, though, Brierley found himself burdened with a homesickness he couldn’t explain. Certain triggers reminded him of India: the hum of a Bollywood song, the smell of an Indian dessert frying atop a stove. Though he had only vague memories of his ancestral village’s surroundings — one was of a water tank near the train station where he lost his brother — they were enough to allow him to scatterplot surrounding landmarks on Google Earth over a period of years and eventually find his home village. There he found Fatima, who’d been looking for him for the past quarter century.

When this story first made news in 2012 — a litany of headlines spoke breathlessly of the “miracle,” which eventually became the basis for Lion, an Oscar-nominated 2016 film — I paid close attention. It wasn’t often that a human interest story about someone with brown skin who speaks Hindi becomes news in the West, particularly with the added component of speaking to this era’s digital capabilities. I was drawn in despite myself.

For those of us whose corners of the world are considered “remote” or “uncharted” from an essentialist white, Western perspective, the interface is far from seamless

Eventually, I ended up sitting down with my mother, who was born and raised in a Bengali village three hours from Kolkata. Together, we try to find her village in West Bengal. It is called Balrampur or Balarampur. She isn’t sure how it’s spelled in English, and neither am I. I haven’t been there in 20 years. Like Brierley with his childhood village, I remember a few landmarks from this place: a playground steps away from my grandparents’ ashram, a muddy lake, a train station. My mother’s home was a structure of three mud-and-brick hut-like edifices, with a garden in front and a chicken coop, but she doesn’t remember its formal address. She hasn’t been there since her father, a widower, died nearly two decades ago; she told me she has no reason to go back since his death.

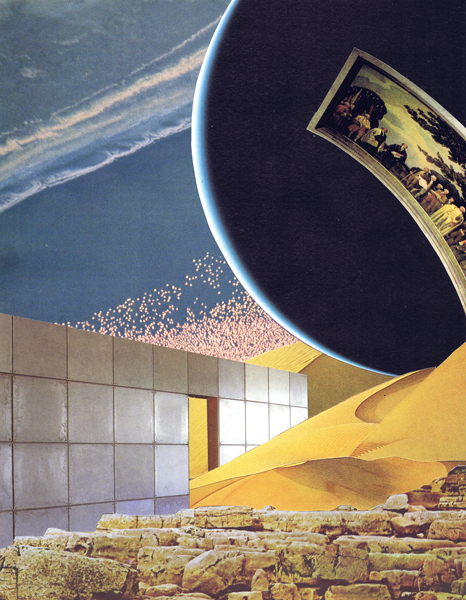

There is no denying Google Earth has a sleek, handsome interface. When I log on to it, a cerulean blue orb pivots along an arc against a pitch-black sky dotted with stars, suggesting a reckoning with vastness. It evokes childlike wonder within me; I feel as if I’m an astronaut orbiting the world. But Google Earth is not a vaccine for everyone’s homesickness. For those of us whose corners of the world are considered “remote” or “uncharted” from an essentialist white, Western perspective, the interface is far from seamless.

When I try to find my childhood home in New Jersey, it obviously doesn’t require years of work. I just type in the exact address, and I’m taken to that congested community of townhouses in North Brunswick. I can make out my driveway, and the picture is crystal clear. I see the sloping pavement that led to my front door, the shared playground in the mossy backyard. A few clicks later and I wander to the Shop Rite and the tennis court nearby. I can spot my local pizza parlor. But the resolution of these satellite renderings is a lot less clear when you are looking in on other parts of the world.

When I type in my mother’s village, Balrampur, it gives me two suggestions in India, one in West Bengal. After I click on that option, I ask my mother if that’s the one, and she shakes her head no. Then we type Balarampur instead, and we’re given another result in West Bengal. I click, and the platform zooms in. There are shades of greige that dissolve into each other, as if someone had just poured a bucketful of water onto a finished painting. There are no discernible landmarks. When I zoom in, the picture gets even hazier. I don’t know where I am. My mother, who lived there for over two decades, doesn’t recognize it, either.

The difficulties we encountered in these searches mirror the hindrances Brierley describes facing in his memoir, A Long Way Home. He detailed how protracted the process was, and the despair it inspired within him as he couldn’t get the technology to comply with his demands. He is guided by a monomaniacal desire to find home, and it morphs into something like a sickness. David Kushner’s 2012 Vanity Fair piece also hinted at difficulties Brierley encountered in a search full of false starts. Though Brierley was crippled significantly by his fading memories of home, the platform itself had many failings too: It hadn’t mapped out a lot of India beyond its major cities, and the Anglicization of certain village names differed from Brierley’s phonetic memory.

In the film, director Garth Davis condenses these years of elapsed time to an inert set of scenes in which Brierley clicks around, furrows his brow, sticks pins in a map he’s mounted on his wall, and gradually grows a beard. In Lion, Brierley’s fortitude is only a small sliver of the story; the real protagonist is Google Earth. Davis depicts Brierley’s homecoming as Google Earth’s triumph. And Brierley has become something a kind of brand ambassador for Google and a fixture in their advertisements. His dogged persistence has become something for the company to brag about.

Brierley’s return to home may well have been impossible without Google Earth. But Lion represents this process as a one-way transaction between an error-prone, sleepless human and an intelligent device, rather than as a human’s struggle to overcome a potentially useful technology’s limitations and biases. In the process, the film flattens the inherently complicated relationship we all have to such platforms, the ways they do not meet our expectations, the ways they occasionally disappoint us, the ways they are inflected by our socioeconomic status and the assumptions and stereotypes that can guide corporate strategies. Lion shies away from such a reckoning; Google’s mapping tools facilitate yet never inhibit. It’s as if the tool were purely neutral and functional, and thus bore no traces of bias from the stages of its development and implementation by its various human minds, from programmers to designers, in the pipeline.

Lion represents Google Earth as a boon for India that can help repair its frayed connections, literally reconstituting scattered families. But such a depiction of technology largely evades the difficult truth of how Google Earth reflects the scars of colonial legacies and has tended to reproduce colonial fractures and reinforce that era’s lasting wounds. When tech companies launch professedly benevolent missions — like, say, Google’s own directive to increase internet access through hot air balloons — in the impoverished pockets of the global South, they can sometimes risk working off hazy assumptions ripped from colonial-era playbooks regarding this “new,” “unexplored” market and its people’s imagined desires without bothering to consult them. This philanthropic rhetoric can come at the expense of a careful, bottom-up understanding of the people whose lives these companies ostensibly want to improve.

Tech companies often work off hazy assumptions ripped from colonial-era playbooks regarding an “unexplored” market and its people’s imagined desires

Such campaigns are often tied to a nominally just mission, as in the way Facebook waltzed into India to supply internet access (with the hopes, eventually, of increasing digital literacy) and walked itself into a blazing failure. “From Zuckerberg’s vantage point, high above the connected world he had helped create, India was a largely blank map,” reporter Rahul Bhatia would write in the Guardian of this red-carpet product rollout. “Many of its citizens — hundreds of millions of people — were clueless about the internet’s powers.”

Zuckerberg’s assumptions soon deteriorated as they met growing opposition from an Indian populace who engaged in a concerted and principled resistance against the company’s hollow claims of betterment through connectivity, pointing out that Facebook’s aims violated India’s vital net neutrality clauses. Facebook primed itself for growth that the country didn’t want, that would seem to come at the people of India’s expense. Its critics likened this exercise to a white man’s burden-style imperialistic project, with messaging couched in the promise of social uplift but with little transparency to its constituency about the particulars of this program. As with many of these schemes, the lack of nuanced cultural understanding tends to lead to bungled execution and broken promises.

Both my parents’ families hail from what is today Bangladesh. During the grisly partition of India in 1947, after the country became independent from Britain, forced migration drove their parents to settle in parts of what became West Bengal, in India. Their sense of home was made fuzzy by historical displacement. As William Dalrymple describes in this New Yorker review essay, the collapse of British stronghold over India resulted in many mass exoduses, the two largest being of Muslims to West and East Pakistan (what are now, today, known as Pakistan and Bangladesh, respectively) and of Hindus and Sikhs to India. In the process of this transit, sectarian tensions flared; many people didn’t make it out alive. Over fifteen million people had been uprooted, and the carnage cut deep, leaving nearly two million people dead, lands forever ravaged, communities destroyed. All of this was the result of hastily drawn borders devised by a British judge over the course of two days earlier that summer, scarcely thought-out decisions with effects that would echo for decades. The particular, errant ways in which communities were splintered along colonially dictated lines has led to a spate of villages that today have no English names.

Technology like Google Earth does not repair these fissures so much as it can highlight them. The inheritance of that period is the very disconnect that is reflected in present-day maps and thousands of villages that register as nondescript, nameless nonentities, villages on Google Earth. The global inequities created by colonial-era decisions — and the material violence these decisions resulted in — are inevitably reflected in a digital map like this. For every town in New Jersey with an image so clear that it triggers a memory charged with sentiment, there is an Indian village with images that are barely intelligible. It’s a way in which hierarchies of dominance of the West with respect to the global South are reproduced all over again, as if to imply that some people’s homes are more important than others. Google Earth is implicated in that era’s reverberating political strife, making Google a de facto neocolonial force, whether or not it intends to be — as if it were replicating the harried, thoughtless actions of that British judge who created villages with uncertain identities.

In this context, Brierley’s real-life situation comes to feel like a crude metaphor for the region’s larger woes. His displacement is the part and parcel of coming of age in postcolonial, rural India, where everyone lives in a state of perpetual homelessness. Lion would like viewers to see a color-blind technology in Google Earth that is healing the wounds caused by colonialism and the uneven development in globalized economy that’s resulted from it, but this narrative merely distracts us from the ongoing legacies of that colonial order, and how globalization revitalizes them.

The lapses in Google Earth’s coverage of India may stem in part from the country’s longstanding resistance to this technology’s reach. The Indian government implicated Google and its mapping technologies in the grisly Mumbai terror attacks over a decade ago. Since then, it has continually asked Google not to make maps of the country that could be used for terrorist purposes. This, as well as other concerns about surveillance and data harvesting, shouldn’t be invalidated wholesale.

It remains to be seen what a humane approach to mapping this world in service of fostering connectivity entails. So long as Google Earth’s capabilities falter for some of those who may need the platform, its stories must be rendered with precision, without a glib sentimentality that covers over political divisions and geographical inequalities. It’s the only way Google Earth can come close to its promise of offering something like home.