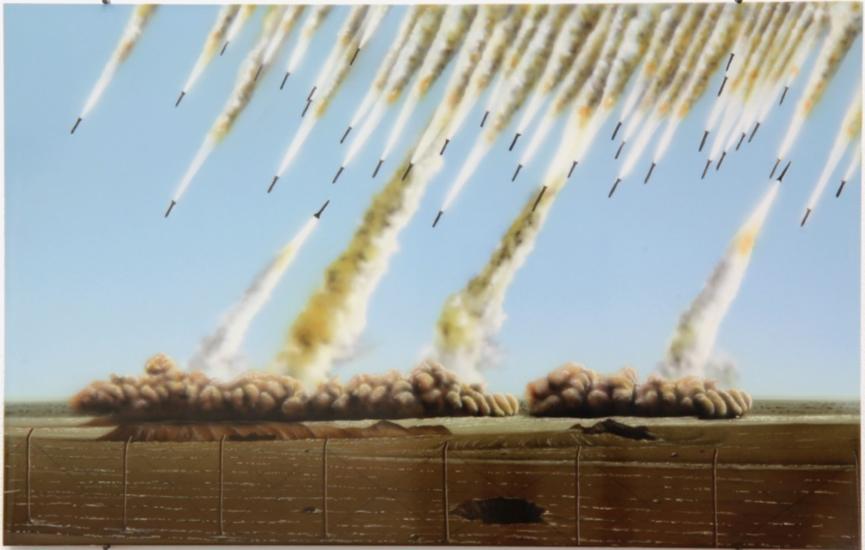

On May 31, 1945, U.S. Secretary of War Henry Stimson called a meeting of experts to advise President Harry Truman on the atomic bomb: Should we use it or not? J. Robert Oppenheimer, the scientist heading the Manhattan Project, was asked to explain the difference between the new bombs and the firebombs already in use. That spring, General Curtis LeMay had been firebombing Japan with napalm, a highly flammable and “sticky” mixture of gasoline and gelling agents. Almost a million people in 60 cities were “scorched, boiled, and baked to death,” in LeMay’s own words, in these napalm raids. It must have been hard to believe that the A-bomb could be dramatically more deadly — so what would it accomplish?

Oppenheimer’s response was that anything living within two-thirds of a mile of the atomic bomb’s blast site would be irradiated, and further, the appearance of the explosion would have its own impact. The meeting notes read: “It was pointed out that one atomic bomb on an arsenal would not be much different from the effect caused by any Air Corps strike of present dimensions. However, Dr. Oppenheimer stated that the visual effect of an atomic bombing would be tremendous.”

The coldness of a cold war depends on reciprocal threat. If it works, the nuclear weapons stay symbols, and we all agree to live in constant low-level fear: the pre-apocalypse

At the time, this was purely theoretical. But six weeks later, Oppenheimer was present for the Trinity test, the first detonation of a nuclear weapon, in the desert of New Mexico. On that early morning of July 16, 1945, after an incredibly bright explosion (witnesses without eye protection were temporarily blinded), the light turned white, then red, then purple. This “purple luminescence,” the effect of ionized atmosphere, smelled like a waterfall. Physicist Robert Serber said that “the grandeur and magnitude of the phenomenon were completely breathtaking.”

The people who worked on the bomb understood that some of its power was symbolic — that the difference between nuclear warfare and previous classes of weaponry was partly aesthetic. In fact, Stimson worried that the power of the symbol might be lost if the bomb were dropped on an already devastated country. He wrote in his diary, “I was a little fearful that before we could get ready the Air Force might have Japan so thoroughly bombed out that the new weapon would not have a fair background to show its strength.” But Oppenheimer had been right about the tremendous effect. The bombs the U.S. dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki felt qualitatively different, even if, in the end, the death toll didn’t match that of the firebombs. As Laurens van der Post, then a prisoner of war in Japan, said, there was “something supernatural” about the atomic blasts.

I’ve often heard that the residents of Hiroshima were warned about the bomb — that the military dropped leaflets on the city instructing them to evacuate. But this is something of a myth. The warnings were vague and not specific to any particular city; LeMay had been dropping leaflets with lists of possible bomb targets for weeks. Although the people of Hiroshima were preparing for attack, they had expected more firebombing and were clearing out fire lanes. They heard air-raid sirens on the morning of August 6, but they heard those every morning. They were not prepared for an entirely new kind of weapon, and the new kind of terror it would bring. As M. Susan Lindee puts it in Suffering Made Real: American Science and the Survivors at Hiroshima, “They had been eating an orange, working in a garden, or reading a book. Minutes later they wandered, without feeling, past corpses, neighbors trapped in burning mounds of rubble, or children without skin.”

The Japanese word for the survivors of the bombings at Hiroshima and Nagasaki is hibakusha. This is not the word for survivor. It is usually translated as “bomb-affected people” or “explosion-affected persons” — a euphemism, almost politically correct. They avoid the more direct term seizonsha (“survivors”) because, as John Hersey writes in Hiroshima, “in its focus on being alive it might suggest some slight to the sacred dead.”

This sounds well-intentioned, but for all its sensitivity toward the departed, the term in practice placed a stigma on the living, who were feared and considered unclean. The Wikipedia page for hibakusha shows a woman with black cross-hatchings on her back and arms — the pattern of the kimono she was wearing burned into her skin. The hibakusha were not inclined to identify themselves as such because it made them less employable and marriageable. There was little financial incentive either, since the Japanese government didn’t offer the victims health care or other compensation until 1957.

I read Hiroshima in junior high, and the detail I remembered most clearly from Hersey’s account was that their eyeballs melted. Those words, that image. I have remembered and re-remembered it so many times — their eyeballs melted — that I became convinced it was a false memory, an invention of my imagination. It seems possible only as a metaphor, but it isn’t. On page 51:

On his way back with the water, he got lost on a detour around a fallen tree, and as he looked for his way through the woods, he heard a voice ask from the underbrush, “Have you anything to drink?” He saw a uniform. Thinking there was just one soldier, he approached with the water. When he had penetrated the bushes, he saw there were about 20 men, and they were all in exactly the same nightmarish state: their faces were wholly burned, their eye sockets were hollow, the fluid from their melted eyes had run down their cheeks. (They must have had their faces upturned when the bomb went off; perhaps they were anti-aircraft personnel.)

This passage informed my entire conception of war. For decades, I have found it difficult to accept that the bombs were necessary. The logical argument has trouble competing with the emotional impact of that etched-in detail.

Now, in its one-sidedness, the little yellow paperback with a red sun on the cover has the whiff of propaganda — but propaganda about what? Is it against nukes or war in general? Was the war necessary? Chillingly, I’ve had the same feeling, that I’m looking at propaganda, in Holocaust museums. How are we to compare these two horrors, if it’s even possible? Am I supposed to choose sides?

Reading about the Hiroshima and Nagasaki attacks, I see propaganda everywhere — axis or allies, pro- or anti-war. The persistent belief that the cities were warned — isn’t that American propaganda? A kind of victim-blaming — they had their chance to escape? In the month before the attacks, Truman wrote in his diary (I’m almost touched that these men of war kept diaries):

Even if the Japs are savages, ruthless, merciless and fanatic, we as the leader of the world for the common welfare cannot drop this terrible bomb on the old Capitol or the new … the target will be a purely military one and we will issue a warning statement asking the Japs to surrender and save lives. I’m sure they will not do that, but we will have given them the chance.

This reads like rationalization, like self-propaganda: They deserve it, even if they don’t deserve it. We can’t do it, but we will. Later, after the bombing on August 6, he would say over radio, “It is an awful responsibility that has come to us. Thank God it has come to us instead of our enemies, and we pray that He may guide us to use it in His ways and for His purposes.” When journalist Wilfred Burchett visited Hiroshima in September 1945, he described the symptoms of acute radiation sickness (severe nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea; swollen, bleeding tissue; hair loss) and called it “atomic plague.” American scientists thought this was Japanese propaganda; they believed that if you were close enough to be irradiated, you’d be dead.

Was the Hiroshima bomb necessary? In 1981, Paul Fussell called this, the title of a point-counterpoint package in the New York Review of Books, “surely an unanswerable question.” This was in an essay first published as “Hiroshima: A Soldier’s View,” later retitled “Thank God for the Atom Bomb.” It is written largely as a response to the “canting nonsense” of moralists “who dilate on the special wickedness of the A-bomb droppers.” Fussell notes that most of the people who feel the use of the atomic bomb was wrong were not lined up for combat in Japan, as he was (“the farther from the scene of horror, the easier the talk”), and goes to some lengths to disabuse the reader of any idea that wartime in the pre-nuclear era was less horrific. He describes marines “sliding under fire down a shell-pocked ridge slimy with mud and liquid dysentery shit into the maggoty Japanese and USMC corpses at the bottom, vomiting as the maggots burrowed into their own foul clothing.” He quotes Glenn Gray, a veteran and author who wrote, “When the news of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki came, many an American soldier felt shocked and ashamed.” Fussell’s response: “Shocked, okay, but why ashamed? Because we’d destroyed civilians? We’d been doing that for years.” In Errol Morris’s The Fog of War, Robert McNamara, who was involved in the firebombing strategy, said LeMay once told him that if the U.S. had lost the war, they would have been prosecuted as war criminals. McNamara wondered, “But what makes it immoral if you lose and not if you win?”

Fussell’s aim in writing this provocative essay, he later explained, was “to complicate, even mess up, the moral picture,” which he felt had been oversimplified by the “historian’s tidy hindsight.” He quotes various men of war: British Admiral of the Fleet Lord Fisher: “Moderation in war is imbecility.” Marshal of the Royal Air Force Sir Arthur Harris: “War is immoral.” General William Tecumseh Sherman: “War is cruelty, and you cannot refine it.” Admiral of the Fleet Lord Louis Mountbatten: “War is crazy.” General George S. Patton: “War is not a contest with gloves. It is resorted to only when laws, which are rules, have failed.” If we follow these arguments, there can be no war crimes — war is war, and the only objective is to kill more of them than they kill of us. War must be total.

However, Fussell’s arguments seem to follow from a premise that he does not complicate or question: “The purpose of the bombs was not to ‘punish’ people but to stop the war.” In this, he says, they were effective; they prevented further land invasions that might have killed him, an American. But it’s far from an undisputed point. Eisenhower thought nuclear weapons were “completely unnecessary,” and a postwar analysis by the U.S. Strategic Bombing Command determined that Japan would have surrendered anyway, with or without the bombs and even without more invasions. As Craig Nelson writes in The Age of Radiance, “They had lost 60 cities; Hiroshima and Nagasaki were just numbers 61 and 62. If they hadn’t given up after losing Tokyo, after all, they certainly wouldn’t because of Nagasaki.” There is evidence that the bombs were used in part to justify their enormous cost, as well as to send a signal to the USSR — quite the power move.

Nukes, like poison gas, can end up killing your own men and not just your enemies, depending on which way the wind blows, so they don’t make very good weapons of war. But in their theoretical potency, their supernatural mystique — Russia’s Tsar Bomba has the force of 3,333 Little Boys, and there are more than enough nukes in existence to destroy all life on this planet — they work very well as weapons of fear. They function as a threat: of punishment by annihilation. As such, Nelson claims, the atomic bombs “did not signal the end of World War II” but “the start of the Cold War.”

The coldness of a cold war depends on reciprocal threat, the idea that assured mutual destruction will act as a deterrent against actually using the things. If it works, the nuclear weapons stay symbols, and we all agree to live in constant low-level fear: the pre-apocalypse. But this system of shared risk, which Thomas Schelling called “brinkmanship,” only works if both parties are rational — if the “adversary is not suicidal,” as Evan Osnos wrote in a recent piece in the New Yorker, “The Risk of Nuclear War With North Korea.” It’s not clear, however, that either adversary, Donald Trump or Kim Jong Un, is rational. Trump has told aides “I will be judged on how I handle [North Korea],” and his approach thus far has been one of strongman aggression. For its part, North Korea is unsure how to interpret him. Osnos’s guide, Pak Song Il, said, “He might be irrational — or too smart. We don’t know.”

Can any game theory of war account for this level of befogged daredevilism? When Osnos asked Pak if his country was really prepared for the possibility of nuclear attack, Pak seemed unfazed:

“A few thousand would survive,” Pak said. “And the military would say, ‘Who cares? As long as the United States is destroyed, then we are all starting from the same line again.’” He added, “A lot of people would die. But not everyone would die.”

It throws a wrench in the works of brinkmanship if mutually assured destruction is seen as a point in nuclear warfare’s favor.

I must have been profoundly uninterested in the news as a child, because I have no direct memory of two major events of 1986 that now obsess me: the Challenger explosion and Chernobyl. Chernobyl is by general consensus the “worst” nuclear disaster in history. But what does “worst” mean? One assumes this is measured by number of casualties, or perhaps some combination of the number of casualties and the cost of the damage. But you learn very quickly when you’re reading about nuclear disasters that it’s difficult to fact-check anything; sources contradict each other and even self-contradict. This is understandable when you consider that the nuclear energy industry was born out of the nuclear weapons industry; the Cold War military complex was naturally prone to secrecy, and the energy industry inherited a serious PR problem.

After Chernobyl, many were diagnosed with “panic disorder” or names that work roughly like “hysteria” — a way of calling people crazy. Chronic stress really does lead to worsened health outcomes. Is fear not real?

I have read over and over that Chernobyl was the worst/biggest/deadliest nuclear accident (of course not counting the bombings in Japan, which were intentional), but one of those sources (The Age of Radiance) also said it was “merely the 14th most lethal nuclear accident in USSR history” — citing for example a 1957 accident at a plutonium plant in the Urals that irradiated 270,000 people and 14,000 square miles of land. The other 13 were kept under wraps until glasnost. Someone must know about them now, but it’s not as though these accidents are common knowledge. So our cultural calculus on what constitutes the “worst” disasters clearly includes how much publicity they get.

In any case, the people most affected by Chernobyl were not aware of those earlier incidents; they had been told, and believed, that nuclear power was safe. The Chernobyl accident resulted (I hate to say ironically, but ironically) from a series of mistakes made during a safety test. The plant operators were trying to determine if the plant could function properly in a power loss due (again … ironically) to a nuclear attack. Unfortunately, Soviet nuclear plants at the time were designed to double as production facilities for weapons-grade plutonium, so they lacked the usual containment shell designed to protect the environs from radiation leaks in a worst-case scenario.

When Chernobyl exploded, workers at the plant and in the nearby town of Pripyat experienced something very like the Trinity test: a purple and pink glow in the sky; a fresh, clean smell like ozone. “It was pretty,” one witness said. They went out and watched it from their balconies like it was an L.A. sunset. If they were quite close, they tasted something metallic. You see this over and over in reports of radiation exposure — a taste of metal, like tinfoil, or in one case, “a combination of metal and chocolate.” Cancer patients receiving radiotherapy describe the same sensation. It’s not the flavor of waves or particles but a phantom taste — a sign of nerve damage.

Workers who realized what had happened called their wives and provided instructions: Swallow iodine, wash your hair, wipe down the counters, throw out the rag. If there’s laundry drying, put it back in the wash. (I was surprised to learn that some radiation is superficial; you can wash it away.) But those workers themselves, and later the many, many soldiers and volunteers who were called on to put out the fires and clean up the accident — called the liquidators — absorbed obscene amounts of radiation. Some could work for only 40 seconds at a time before reaching the lifetime limit of exposure. According to The Chernobyl Nuclear Disaster, a textbook-like account by W. Scott Ingram, Chernobyl’s director Victor Brukhanov

realized then that his closest assistants were in a condition of shock. He became even more alarmed when he asked a health worker that he encountered to take a reading of the radioactivity in the atmosphere. The instruments measured radioactivity in units called rems. A reading of 3.6 rems was considered high. The health worker told Brukhanov that the needle went off the dial at 250 rems. In other words, most of the people in the building and on the grounds had received deadly doses of radiation.

These workers faced a troublesome choice: The protective clothing was so heavy that it made them move more slowly, and it was harder to get in and out quickly. So many simply didn’t wear it.

The people in the zone of evacuation were incapable of processing the disaster. Life had not given them equipment to process it. In Chernobyl Prayer (sometimes translated as Voices of Chernobyl), Svetlana Alexievich collects 300 pages of testimony from survivors — the hibakusha of Chernobyl, the “Chernobyl people.” (“You’ve got a wife, children. A normal sort of guy. And then, just like that, you’ve turned into a Chernobyl person.”) Alexievich writes:

The night of April 26, 1986. In the space of one night we shifted to another place in history. We took a leap into a new reality, and that reality proved beyond not only our knowledge but also our imagination. Time was out of joint. The past suddenly became impotent, it had nothing for us to draw on; in the all-encompassing — or so we’d believed — archive of humanity, we couldn’t find a key to open this door. Over and over in those days, I would hear, “I can’t find the words to express what I saw and lived through,” “Nobody’s ever described anything of the kind to me,” “Never seen anything like it in any book or movie.”

When a tsunami rises over a city, or a plane flies into a skyscraper, we say it’s “just like a movie.” This suggests that in some subtle way, disaster movies help us process disaster — it’s the only exposure most of us get, outside of news clips, to deadly spectacles. (And we don’t watch the news on big screens.)

In Survivor Café, Elizabeth Rosner notes, “When I ask Holocaust survivors to tell me their stories, I notice them flinch at the word. It’s as though ‘story’ implies something invented, a fairy tale.” Chernobyl Prayer does not feel like a collection of stories, with structures imposed retroactively. It is simply people talking, relating their experience. Many speak of their fondness for jokes: “I don’t like crying. I like hearing new jokes.” Here’s a good one:

There’s a Ukrainian woman sells big red apples at the market. She was touting her wares: “Come and get them! Apples from Chernobyl!” Someone told her, “Don’t advertise the fact they’re from Chernobyl, love. No one will buy them.” “Don’t you believe it! They’re selling well! People buy them for their mother-in-law or their boss!”

The Chernobyl people don’t like to dwell:

I was struck by the indifference with which people talked about the disaster. In one dead village, we met an old man. He was living all alone. We asked him, “Aren’t you afraid?” And he answered, “Of what?” You can’t be afraid the whole time, a person can’t do that; some time goes by, and ordinary life starts up again.

There are dozens of comparisons to war — it was the closest available analogue. (In fact, nuclear accidents are usually spoken of in terms of “Hiroshimas.” It’s become a unit of measurement.) “We’d grown used to the idea that danger could only come from war.” “It was a real war, an atomic war.” “Just like in 1937.” “Instead of assault rifles they gave us spades.” “Is this what nuclear war smells like? I thought war should smell of smoke.” “They call it ‘an accident,’ ‘a disaster,’ but it was a war. Our Chernobyl monuments resemble war memorials.”

If it was a war, it was a war with no clear enemy: “To answer the question of how we should live here, we need to know who was to blame. Who was it? The scientists, the staff at the power plant? Or was it us, our whole way of seeing the world?” Another:

At first, it was baffling. It all felt like an exercise, a game.

But it was genuine war. Nuclear war. A war that was a mystery to us, where there was no telling what was dangerous and what wasn’t, what to fear and what not to fear. No one knew.

When Wilhelm Röntgen discovered X-rays in 1895, he named them X because they represented the unknown. This gets at what was, and is, so uncanny about radiation: You can’t see it, only its effects. One cameraman sent to film the scene at Chernobyl after the fact said, “It wasn’t obvious what to film. Nothing was blowing up anywhere.” But some people, it seems, are immune to this fear of the unseeable; they refused to evacuate or later returned to the contaminated land, the zone of exclusion, because “I don’t find it as scary here as it was back there.” They chose contamination over exile, the invisible over the visible threat. “This threat here, I don’t feel it. I don’t see it. It’s nowhere in my memory. It’s men I’m afraid of. Men with guns.”

As a whole Alexievich’s book is stunning, but difficult to take. It is bookended with two long monologues from women who lost the loves of their lives in the accident. They watched their husbands become unrecognizable: “His nose got somehow out of place and three times bigger, and his eyes weren’t the same anymore. They moved in opposite directions.” He begs for a mirror and she refuses. “I just didn’t want him to see himself, to have to remember what he looked like.” The other woman was pregnant, and while she sat at her husband’s bed in the hospital, the baby inside her absorbed radiation “like a buffer.” It was born two weeks early and died within four hours.

In their gut-wrenching grief, these monologues remind me of Marie Curie’s Mourning Journal:

They brought you in and placed you on the bed … I kissed you and you were still supple and almost warm … Oh! How you were hurt, how you bled, your clothes were inundated with blood. What a terrible shock your poor head, that I had caressed so often, taking it in my hands, endured. And I still kiss your eyelids which you close so often that I could kiss them, offering me your head with the familiar movement which I remember today, which I will see fade more and more in my memory.

Pierre Curie, severely weakened from radiation exposure, had fallen into the street and had his head run over by a horse and carriage.

In 1989, a group of journalists from the Chugoku Newspaper based in Hiroshima began writing a series of global investigative reports, now collected in a book called Exposure: Victims of Radiation Speak Out. One of these reports quotes an anti-nuclear activist in the Soviet Union: “All the radiation sufferers of the world have to unite!” Another describes the phenomenon of “radiophobia”:

To describe the state of mind whereby a person becomes paranoid about radiation and its effects, the Soviet media often uses the word radiophobia. It expresses the feelings of the Soviet people, who are torn between the truth as told to them by the government, and the rumors they hear through unofficial channels.

Like the Japanese concept of hibakusha, Soviet radiophobia can be extended to other nations. Conspiracy theories bloom around nuclear anything because there is so much mis- and conflicting information. Paul Fussell supported the use of the atomic bomb — and he repeats the common wisdom that Hiroshima was warned — but not nuclear energy, or “the capture of the nuclear-power trade by the inept and the mendacious (who have fucked up the works at Three Mile Island, Chernobyl, etc.).” Long-term studies of survivors in Japan, Ukraine, and Belarus have shown that ranges of exposure previously thought to be highly dangerous are only slightly dangerous — with incidences of cancer perhaps five percent higher than the normal population. (We all have some exposure to radiation through daily living, not just from X-rays but from ordinary activities like eating bananas or taking a walk.) The people most at risk in a nuclear disaster, it turns out, are emergency workers and children, who are especially prone to thyroid cancers.

But this doesn’t tell us much about the psychological effects of exposure. After Chernobyl, many were diagnosed with “panic disorder” or something called “vegetovascular dystonia,” names that work roughly like “hysteria” — a way of calling people crazy. A report of the International Atomic Energy Agency supposed that “the designation of the affected population as ‘victims’ rather than ‘survivors’ has led them to perceive themselves as helpless, weak and lacking control over their future.” Again, it seems, the nuances of terminology influence degrees of stigma.

You can’t prepare for the worst-case scenario when the scenario keeps getting rapidly worse

However, other studies have shown elevated stress levels in populations exposed to nuclear accidents even years later (for example, those living near Three Mile Island). Hersey, when he visited Hiroshima again 40 years after the bombing, described a “lasting A-bomb sickness” marked by weakness, fatigue, dizziness, digestive problems, and “a sense of doom.” Chronic stress really does lead to worsened health outcomes. Is that not real? Is fear not real? There’s a tension in the literature around nuclear disasters, between the need to accurately describe them as they are — a kind of nightmare sublime — and to balance out “hysteria” and present the “facts.” It’s difficult to reconcile the horror of nuclear disasters with our ability to move on. Where “Chernobyl people” tell jokes, the Japanese say “Shikata ga-nai” — roughly, “it can’t be helped.”

It’s hard to talk about the hibakusha without succumbing to fear mongering and nuclear phobia. So here’s a fact: There have been many more deaths, orders of magnitude more, from accidents in the fossil-fuel industries than in nuclear energy. But I can’t think of a particular accident with as much disaster capital as Chernobyl. In 2010, there were “the 33,” the trapped coal miners in Chile, but they all survived and became heroes.

Why are some deaths more horrifying than others?

In the spring of 2013, I often drove north on Route 93 in Colorado from Golden to Boulder. It’s a gorgeous, hilly route, through yellow-green grassy fields, with misty blue mountains on your left, but dangerous in the snow; I know someone who totaled their car on that road. It snowed a lot that spring, to a maddening degree, once or twice a week right up through the end of May, but the snow made it even more gorgeous and misty, and sometimes I saw herds of antelopes.

About midway between Golden and Boulder, you pass Rocky Flats on your right. This area housed a plant that made plutonium triggers for nuclear bombs; it closed in 1992. What was the plant is now a Superfund site. The plant’s first accident occurred on September 11, 1957 (the same year as that mysterious accident in the Urals), with another major and nearly catastrophic fire on Mother’s Day in 1969. Waste was found to be seeping into open fields. In 1970, airborne radiation was detected in Denver. But the unsafe conditions continued for years, until informants tipped off the EPA and FBI, triggering a raid in 1989. Where was our glasnost? The hibakusha of Colorado filed a lawsuit, but after twenty years it was denied.

Until recently, there was a bar across the street from the site called the Rocky Flats Lounge — a truly great bar, kind of a cowboy bar, with an open back so you could watch the sun set over the mountains to the west. There were horses in view. They had karaoke on the weekends, and I once heard the bartender, a woman, sing a devastating version of “Fake Plastic Trees.” They sold T-shirts and tank tops bearing mushroom clouds and the words I GOT NUCLEAR WASTED AT ROCKY FLATS. The bar is now permanently closed; it kept catching on fire.

I’m telling you this because I keep thinking about it. I keep thinking about Hurricane Irma; there were upwards of 80 Superfund sites in its path. What will become of them? The EPA is being dismantled. I keep thinking about Fukushima, the new hibakusha it created. Japan sees earthquakes and tsunamis all the time; they have a culture of disaster preparedness. But preparation takes time. Before 2011, most seismologists believed that earthquakes with magnitudes of higher than 8.4 weren’t possible in Japan. Climate change accelerates natural disasters. Earthquakes cause tsunamis and volcanoes, and volcanoes and earthquakes cause tsunamis; global warming leads to increases in all three. You can’t prepare for the worst-case scenario when the scenario keeps getting rapidly worse.

In a lyric essay about epilepsy and the Cold War, a writer who calls himself “Mike Smith of Albuquerque” includes this snippet of faux dialogue, an apt depiction of life in the pre-apocalypse:

Q:Could you talk about the Challengerexplosion in the context of the Cold War?

A: I … guess so. Well, all those shuttles were a product of the U.S./U.S.S.R. space race, for one thing. And after the Challenger, when Chernobyl exploded and burned three months later, it felt as if some doomsday pattern was beginning. Everything was going to explode. Nothing was safe. Of course, I was just a kid, and what did I know, the world’s more-or-less fine.

This is how I feel all the time now. Nothing is safe. Everything’s fine.