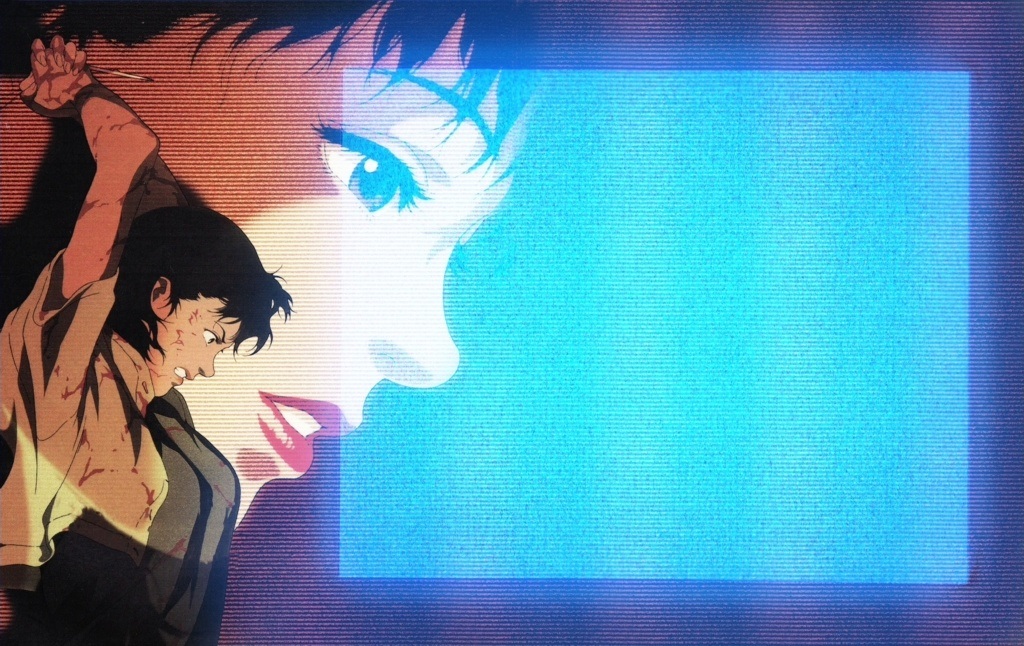

You don’t believe her from the start. A woman in costume sings on stage. The men in the audience — and there are only men in the audience — train their lenses on her. In a sharp match cut, the same woman picks out a cabbage in the supermarket, her headphones on, blaring pop, as she considers which milk to buy. From the first scenes of Satoshi Kon’s Perfect Blue (1997), the woman, Mima Kirigoe, is split. There is Mima the “pop idol,” the hired act, singing with a trio on stage, obsessively adored. And then there is the “real” Mima, the non-performer Mima, picking out food for her pet fish and riding the subway: a little too vulnerable, a little too earnest, a little too uncertain. Are we witnessing her reality or indulging in her fantasies?

Kon’s films lucidly excavate this ambiguity. His characters plunge into the split between the subject and her representation, the public and the private persona, the waking self and the dream self, the on-screen act and the off-screen spectator. Performance and projection — what is shown and what is reflected back — blur. Screens become mirrors, and mirrors shatter. Reality catches her reflection. Or is she caught in its gaze?

Prefiguring the dizzying consequences of avatars and deepfakes, the Mima of the internet becomes realer to Mima than herself

When Satoshi Kon agreed to adapt Perfect Blue for his directorial debut, he was given a simple premise, taken from a 1991 novel by the same name: a pop idol is targeted by an obsessive, violent fan. This was the mid 1990s; psychological thrillers dissecting the “sickened criminal mind” proliferated. Kon, uninterested, chose in his adaptation to focus not on the psychological fragmentation of the criminal, but of the victim. He also teased out a thread he would return to throughout all of his films, concluding in 2006’s Paprika: the borderline between dreams, fantasies, memories, and “reality.” The concept of the borderless, he noted in a 1998 interview, was overplayed. Kon, who died at age 46 in 2010, worked through this theme of borders and ruptures in a decade when older metaphors for splitting — split identities, fractured memory, waking dreams — were already being projected onto the latest split: that between the IRL and the virtual. Situated a few years after the commercial and everyday use of the internet were already gaining ground, after the “weblog” but just preceding the launch of Google and Napster, Kon’s work perceived the fissures between the exteriority of the “virtual” persona and interiority of the person incorporating or creating it: Who — Kon poses — is reflecting whom?

Kon is himself underplayed — too unconventional for both the Western anime grazer better acquainted with the fables of Hayao Miyazaki or the cyberpunk visions of Ghost in the Shell and Akira, and the purist, who, in scholar Susan Napier’s words, might consider Perfect Blue’s “contemporary urban setting, sophisticated narrative, and highly realistic visuals” more appropriate for “a live action film than a conventional anime.” Kon’s films arguably have more resonance to, as critic J. Hoberman notes, the films of directors like David Cronenberg and Olivier Assayas, and even, as Napier notes, Alfred Hitchcock and David Lynch, than to Miyazaki. Kon’s influence on American filmmakers is well-documented: Perfect Blue is a more realized Black Swan (Darren Aronofsky also cited Perfect Blue as a direct inspiration for scenes in Requiem for A Dream) and Paprika is a superior Inception. Apart from their influence, Kon’s films are in themselves prescient representations of technology’s ability to both rupture and manufacture the real.

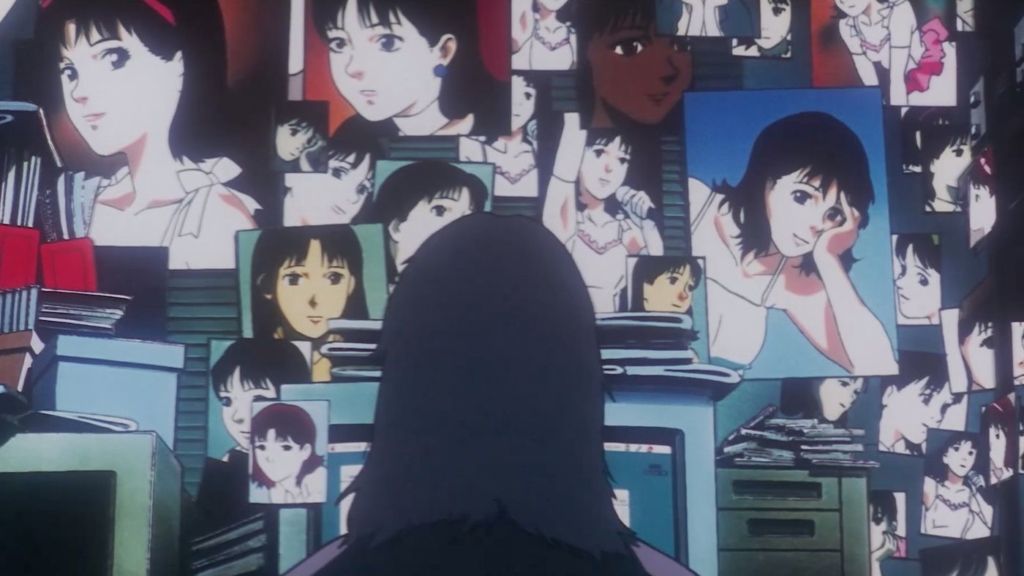

For Mima in Perfect Blue, the question of reality is posed through her self: Who is she, really? The pop idol Mima is manicured and virginal, embodying the Japanese symbol of shōjo, a young, innocent girl. Mima yearns to break out of the constraints of this idealization, to become more real. “The pop idol image,” she reasons, “is suffocating me.” She decides to make it as an actress. An actress, in this logic, is not a prop or a doll. She is an actor, agentive. Not a receptacle for the projections of others, but a manipulator of them. Her (male) managers support her. Her fans — one particularly obsessed fan — does not. His real Mima is the pure idealization of the pop idol, the fantasy woman who, in his imagination, intends to erase the everyday Mima, who is a traitor. On the surface, Mima does not let this fixation cloud her resolution to puncture her shōjo image. But privately, she has her doubts. The question of reality shifts from her self to her desire. What does she really want? Her manager asks: Is she willing to do a nude photoshoot? Is she willing to film a rape scene? Yes, she says, even as the traumatic (re)enactment of sexual exploitation, a literalization of her role as a performer, causes her to break down in remorse and self-doubt.

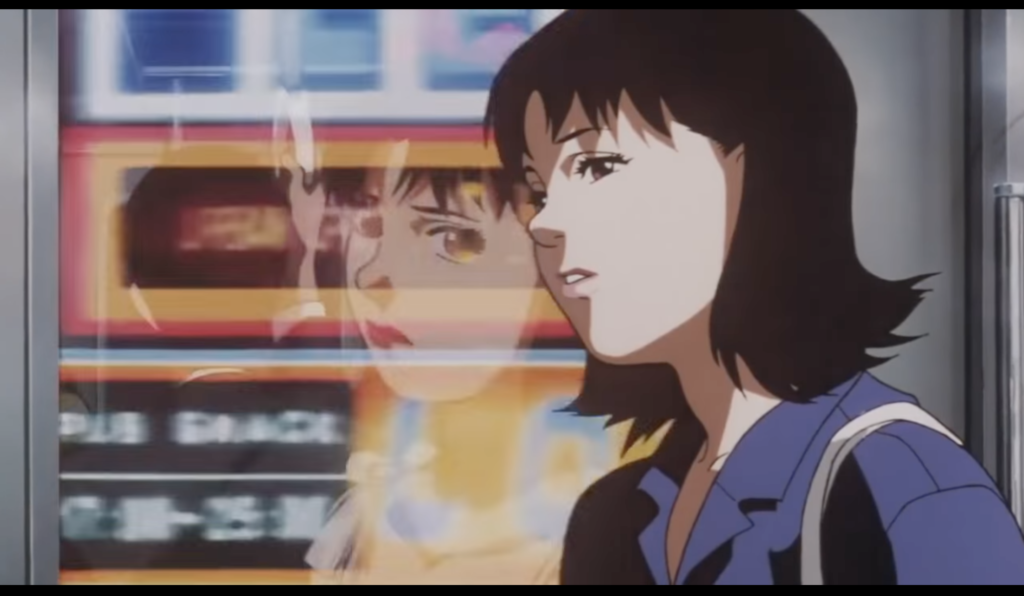

Each cleave from her past self splinters her further, until she fully splits into two: Mima and Mima’s conscience — her guilt, her confusion, the projections of others entwine with her own internalized judgement. This shadow self hardens into an embodiment of her pop idol self, a freakishly cute shōjo who relentlessly haunts Mima. “Who are you?” — Mima’s single line in her first acting stint for a show called Double Bind — reverberates. Who are you, she asks: first to herself, then to her stalker, then to her hallucinations. Mima’s sense of reality starts to fragment, an experience Kon piercingly evokes through seamless jump cuts that dissolve the audience’s sensitivity to what she thinks she is seeing: either the “real world,” the fictional world of Double Bind, Mima’s waking hallucinations, or Mima’s dreams. In another scene from Double Bind (although even this grounding begins to feel tenuous) Mima, in character, tells the series’ star, Eri Ochiai: “I don’t know anything about myself anymore!” to which Eri, playing a psychiatrist, responds: “Well, how do you think you know that person you were a second ago is the same person you are now? A continuous stream of memories. Given only that, we all create illusions within ourselves.” What if, Mima’s in-character worries go, these illusions begin to act independently? Eri-in-character reassures Mima-in-character, “It’s all right. There is no way illusions can come to life.”

The internet — the final dimension of the film — destabilizes even this certainty. Illusion is no longer safely sequestered in “one’s head.” On the internet, Mima learns, illusions can become real, or at least indistinguishable from reality. Mima’s stalker, who goes by Mimania (or Memania), creates a website called MimasRoom.com where he details his obsession by posing as Mima on the internet. From her bedroom, Mima scrolls through a disturbingly accurate description of all of her movements throughout the day, as if written by her. As her sense of reality deteriorates, the real threat of Mimania’s stalking merges with her own hallucinations. Her other, pop idol self begins to talk to her through “Mima’s Room,” not just impersonating, but actually usurping Mima. “The real Mima,” the website reads “is writing this.” Once Mima — and the viewer — are sputtering in the discontinuous spell of hallucinatory reality, “Mima’s Room” becomes the only realiable record of what Mima has actually, or presumably, done. In a move that prefigures the dizzying consequences of social media avatars and deepfakes, Mima finds that the “real Mima” of the internet has become realer to Mima than herself.

I won’t spoil the twist. Suffice to say, Kon aims the narrative arch, at least in Perfect Blue, towards a reestablishment of the real from the grips of hyperreal simulacrum, be they psychic or virtual. In the end, there is a “real” Mima, even if that sense of a “real,” “true,” or “authentic” Mima is, in the words of Eri, just another thinly woven and vulnerable illusion. Kon depicts Mima’s puncturing of that illusion, her suspicion that her performative alter ego or her internet avatar are realer than she is, as a terrifying psychosis. Mima, who is at first an easy target for the projections and over-identifications of others, must, in a moment of self-affirmation and agency, reassert her “true self.” I found something slightly disappointing, even if a little relieving, in this conclusion. Mima lives, thankfully. Yet there was a dull edge of neatness in being returned to a stable sense of reality, with the dream and digital realms safely contained away from “the real.” The irony is that Kon, who was prying open the boundaries between these seemingly separated realms, in the end, at least in Perfect Blue, ends up reasserting a digital and psychic dualism. Yet watching Perfect Blue incited a visceral experience of augmented reality. Watching Mima’s “breakdown” is so mesmerizing because Kon, through his animation and direction, undoes the boundaries that differentiate dream from reality, from hallucination, from the digital. This augmented realm disorients and entrances. It felt spellbound by the thick surreality of Mima’s mind.

In Paprika, the internet, like the unconscious, becomes a theater for excess libidinal energies otherwise excised from waking life

If, in Perfect Blue, the split self is parasitic and psychotic, and can only be contained through a life-or-death victory of the real, in Paprika Kon delivers a less fraught twinship between a “real” woman and her dream alter ego. Based on a 1993 novel by Yasutaka Tsutsui, Paprika is set in a near future where a group of psychotherapists have developed a machine that allows them to enter and manipulate another person’s dreams. The DC Mini, as the machine is called, is both miraculous and potentially dangerous. Kon parodies the “boy genius” recklessness of Silicon Valley disruptors in the character of Dr. Kōsaku Tokita, the DC Mini’s inventor, whose excessive weight and childlike obsession with toys underscore his shrugging off of moral responsibility for his invention. Even though the DC Mini is still not regulated or approved for therapeutic use, Dr. Tokita and his collaborator, Dr. Atsuko Chiba, use it to treat psychoanalytic patients. Atsuko’s dream alter ego, Paprika, is something of a dream doula, walking alongside her patients through their dreams, intervening and interpreting. As the film opens, Paprika is treating Detective Toshimi Konakawa for a paralyzing anxiety that prevents him from solving a murder case. At first they meet in a hotel room, where Konakawa, hooked up to the DC Mini, falls asleep and Paprika, also connected to the machine, watches his dreams, which she can then replay like a film to the awoken patient. For their next meeting, Paprika tells the detective to visit a website — Radioclub.jp. At his desk, he types the address and seamlessly falls through the screen and into a bar, Radio Club, where Paprika is waiting for him. “What is this place?” he asks. “A counseling room. A meeting place. A date spot,” she muses. “Don’t you think dreams and the internet are similar?”

Kon certainly does. In Paprika, the internet, like the unconscious, becomes a theater for the excess libidinal energies otherwise excised from waking life. As Paprika concludes, the internet and the dream are “both areas where the repressed conscious mind vents.” Like the DC Mini, the internet browser is a portal. And this technology, Paprika warns, is hackable. After several psychiatrists at their research lab, the Institute for Psychiatric Research, suffer sudden mental breakdowns, Atsuko and Tokita realize that someone has stolen a DC Mini and is manipulating the dreams of its users. They rightfully suspect it as an inside job. They discover the chairman of the Institute, Dr. Seijirō Inui, is behind the attacks. Here, Paprika better reflects the risk of artificial intelligence — not that the technology itself will become sentient, but that it will be manipulated by those already in power, who consider themselves, like the chairman does, “protectors of the dreamworld.” The DC Mini, in the corrupt hands of the powerful, uses the dreams of its users. The victims become trapped in a collective nightmare, astoundingly rendered as a nonsensical, deranged parade littered with everything including domestic objects, toys and anthropomorphic avatars, power-hungry politicians and literal talking heads, fortune and poverty, photographic exhibitionism and voyeurism, and even the weather report, all combined into a sing-song manic celebration and marching incessantly. It’s not a bad metaphor for a Twitter feed. This collective delusion begins to spill into reality. Like the internet Mima of Mima’s Room, or perhaps, like internet-bred conspiracy theories, the nightmare usurps the real, or at least makes the distinction between reality and delusion paper thin.

What can we learn from these films? Perhaps: Don’t be too quick to believe what you see. Kon never lets you, as a viewer, stay comfortable in the certainty that what you are seeing is, within the story, “real.” Might one also understand Kon’s films as some sort of critique of the growing instability of reality, warning that this can lead, in Mima’s case, to individual psychosis, or in Paprika’s, to collective psychosis? It might help to consider Kon’s Millennium Actress (2003), another story where memory, reality, and fiction blur. In it, a renowned Japanese actress remembers and reen-acts her life through her various film roles, whose stories also trace Japanese history. In Millennium Actress, the mimesis of film offers a more harmonious blending of fact and fiction. Fiction can, in its twisted forms, like deepfakes or conspiracy theories, disturb the real in threatening ways, as Perfect Blue and Paprika warn. But fiction can also reflect reality without having to stake some artificial claim in the authentic. After all, as Dr. Toratarō Shima, another psychiatrist from Paprika considers, “all truth comes from fiction.”

This is why Kon’s films succeed not despite, but precisely because, they are rendered through anime — an animation aesthetic that is acutely aware of, and even exploits, the fact that it is hand-drawn (a humbling fact, when you consider the depth of detail in these films). Unlike live-action film, or even other forms of computer-generated animation that seek to create “realistic” images, anime leans into the stylized, symbolic nature of representation. It’s not trying to be real, but it is trying to evoke something true. Kon’s films explore the disintegration of reality through a medium that is conscious of its own simulation of reality. At the same time, the seamlessness of his animation means his films are simultaneously highly constructed and hyperreal. Not real, but as true as a story is true. Perhaps this is what Kon’s films can teach us about the internet — we should take it in as we might take in his films, never forgetting that we might, at any moment, be witnessing someone’s fantasy, someone’s dream.