Netspeak is hardly the first abbreviated language, but it was ours.

Perfected by the necessities of a pre-T9 cellular world and a flippancy embedded by the instant fact of now instant communication, the code gave us a standard to lean on with the A/S/L-level depth we desired. This is not a lead-in to diagnose the shallowness of a generation to whom shorthand merely meant halfhearted scramblings down a wide-ruled notebook. Netspeak, for all its acronyms and grammatical grievances, transmitted the real feels infused by its users, evinced now by our potent reminisces of both it and the late-’90s, early aughts internet on which we created it. (If we have to take responsibility for face-to-face connectivity problems, academic coddling, intergenerational workplace strife, political complacency, and participation trophies, at least give us this.)

We’re far gone enough to nostalgia about Web 2.0, and it’s worth noticing that its defining communicative features have come back in a big way. The general features that mark the cool of current internet vernacular—u, ur, r, k, proper noun i—also look rather old school. It’s not quite the pages of a Lauren Myracle novel brought to life—ttyl, the best-selling young adult novel she published in 2004, was written entirely in instant messages—but nor would her characters’ general disregard for case look out of place in today’s digital communicative landscape. Promo material for the book’s 10th anniversary reissue claims that with a visual and cultural makeover the novel is now “ready for the iPhone generation.” Ironically, as if the novelty of the full mobile keyboard has worn off, the iPhone generation now speaks more akin to the generation that inspired Myracle over a decade ago.

Animatedness means being moved, like a puppet by a puppeteer desperate to prove the humanness of their object.

Before we submit to our emojilords, it’s worth asking about these ghosts of internet’s past that have wormed their way back into our language. Why are you back? Why, when Swype exists, when autocorrect has long surpassed its quaintisms, at a time when even basic dum-dum burner phones are equipped with slide-out keyboards?

Why do we need you?

Animative expressive forms are the new normal.

Once limited to the domain of niche forums and Tumblr, reaction gifing is more accessible than ever. Gifs have not only made it onto the mainstream social media stage—with Facebook, naturally, the reluctant straggler—but all manner of platform-supported gif buttons and third-party plugins means that even users farthest from hip to the corners of internet quirkdom can now be part of the fun. (As someone who still uses her carefully curated multiple folders of bookmarked gifs, I’ll cry hipster on this one.)

Emojis, too, have received the gif treatment—or perhaps it’s the other way around. Though their creation predates the iPod, many first encountered the unicode set as an obscure side benefit to iMessage.

Now they are very nearly legible to every device out there (despite interpretive discrepancies between platforms, due to literal differences in representation of the very same emoji). The custom-made-celebmoji trend has jumped the A-List. An emoji Bible—subtitled “Scripture 4 Millennials” (*me: screaming*)—can be purchased in iBooks for $2.99. An actual emoji movie is in the works. They’ve wreaked havoc for medieval-alphabet coders. They inspire albums, like Lemonade, or almost inspire albums, like Wave. They have leaped from the screen onto crop tops and been stuffed with plush. And we have just gotten 72 new ones.

And yet, the proliferation of both access and options for these forms seems rather oblivious to how they are used. As Amanda Hess writes in the New York Times, “when emojis and gifs are filtered through the interests of tech companies, they often become slickly automated.” In the case of the gif button (presented alongside the “photo” and “poll” options for tweets), neat categories—“Agree,” “No,” “Wink”—run contrary to the “curatorial sensibility” embedded in the practice: Reaction gifs are often used to convey affects that escape pithy representation, such as “white people explaining diversity to me.” As per usual, it’s as if the techies behind the trend are pushing product with no thought as to who’s using it or whether it’s being used at all.

If Matt Grey and Tom Scott’s Emojli—an emoji-only messenger where even user names are emoji-only—were real and not satire, we might really have reason to believe “the end of [emoji] days” is near. Part of me thinks the quick end, like that of a good-time meme that burns too hot to last, might be more merciful than the current process: oversaturation, or slow death by drowning.

How do you combat online animatedness? You chill out.

We have plenty reason to see this coming. We know what happens to idioms that reach critical mass; more important, how the process of popularity in fact necessitates a kind of ironic reduction of the object. The unique, inventive aspects that make us want to pass it on must be shorn off for maximum circulation and accessibility. The examples are endless: Consider the relatively recent fates of “basic,” “Netflix and chill,” and “squad,” words sourced and repurposed from Black vernacular for, it seems, the sole purpose of later writing a jaded testimonial about them. Linguists identify the processes that make up this phenomenon as entextualization, transduction, and—as many nonlinguists know—appropriation. Entextualization describes the making moveable of an idiom; induction is its actual relocation; and appropriation, taking on that which has been displaced as one’s own.

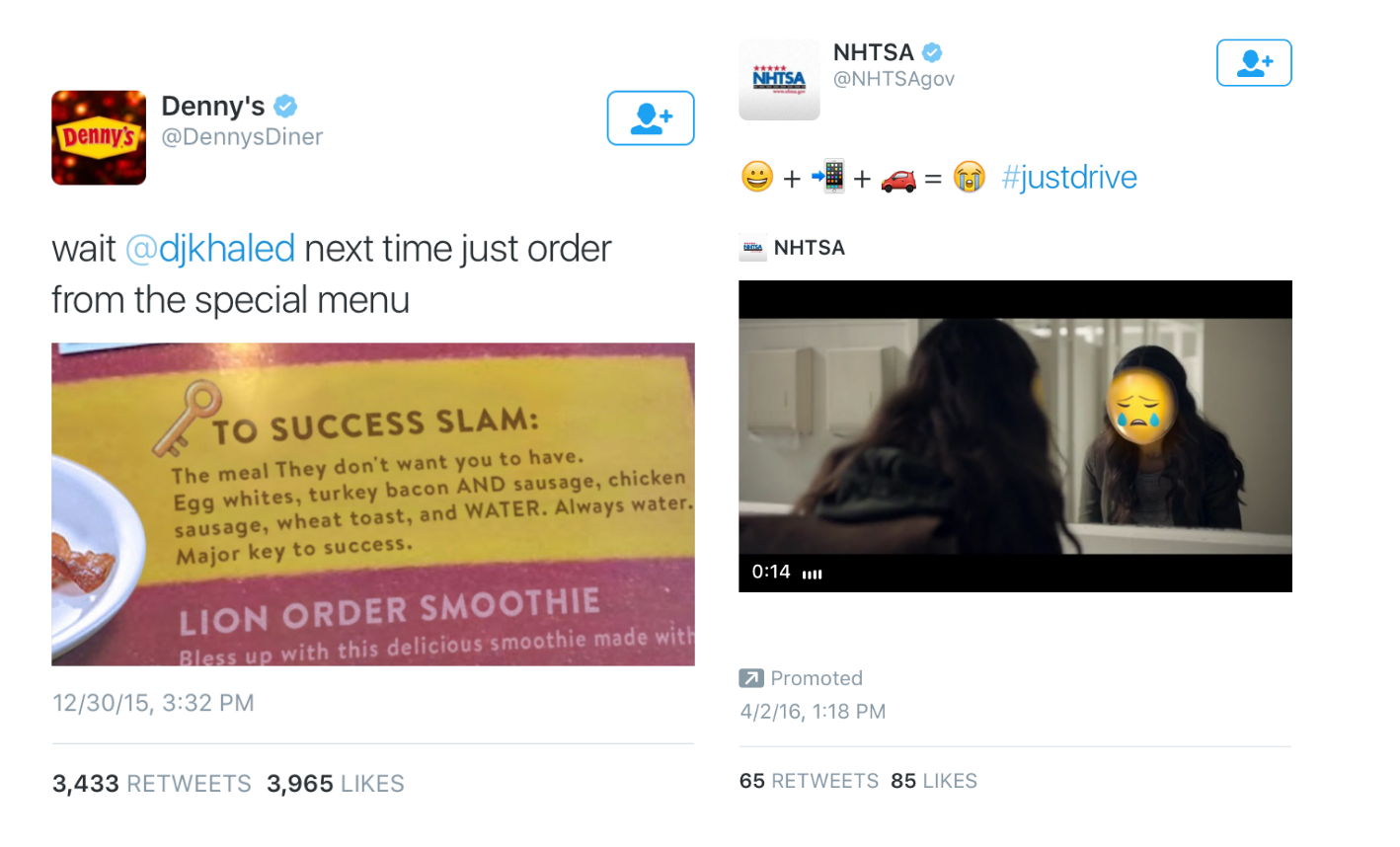

The ever encroaching desire of white people to be relevant is a heady fuel source, and not entirely unrelated is the ability of corporate voices to send anything cool to an early grave. Kate Losse on what she calls “weird corporate twitter” investigates the appropriative relationship between social media accounts verified and run by major corporations and absurdist accounts (“weird twitter”). Gifs and emojis are no exception. Denny’s remains a predictable repeat offender, and other examples include Taco Bell, DiGiorno, and even the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, which shows how “an emoji can wreck your life” (if you use them while, uh, driving).

Much like meme attempts, these make for cringeworthy affairs akin to watching an early 20-something assert their “with it” chops to a bunch of high schoolers. As ironically cool as it might be to engage in a parental emoji exchange, Big Brother co-opting a beloved quote just bucks anything like the kind of in-group “it me” commonality of memes, gifs, and emojis that underlies each share. But corporations have always done the most to inhabit the language of their consumers. While Hess fears the effect of political and financial imperatives on digital culture, Losse hits upon a particularly distressing issue to do with authenticity and recognizability in digital nonspace: Has corporate parasitism of internet vernacular actually outpaced our ability to sense it?

To really answer that question requires a guarded look away from corporate appropriation to the internet folk who shape digital language from below. From a user perspective, these once exciting features that are supposed to surrogate affect—by advocacy, if not etymology—look a bit too conventional to do so. As with many, many, many idioms before them, widespread and corporatized use hasn’t evacuated their meaning entirely (an impossibility?), but they do seem rather tainted by the tryhardism of it all. Emptied of … something. Corny. Uncomfortable. Too much. Hyperanimative.

Animatedness is an ugly feeling. So identifies Stanford professor Sianne Ngai in her study of the aesthetic phenomenon in a monograph called Ugly Feelings. Animatedness, or excess liveliness, is compulsory: It involves not only the expectation that a body be agitated at will but requires “an unusual immediacy between emotional experience and bodily movement.” It’s quite literally the “state of ‘being moved’” like a puppet by a puppeteer desperate to prove the humanness of their object. And sometimes that object is an objectified subject who, too, aspires to a humanness at odds with the jerky movements of their manipulated body.

Animatedness, the aesthetic that makes the characters in Uncle Tom’s Cabin, in Eddie Murphy’s The PJs, and the exemplary Taylorist worker all so disturbing, also bears upon the gif. “Gifs are like haunted pictures,” says writer Alyson Lewis, whom I asked about her general dislike for the format. Between “classic reaction pics,” still images that “drive the message home on [their] own,” and Vines, Lewis locates gifs in an uncomfortable space that gathers the best features from either side in the most fragmentary way. Something about them feels … off. “There’s text at the bottom when someone’s speaking, but the snippet is usually such a fraction of the moment that the moving lips don’t match up with it.”

In Lewis’s formulation, the gif as a social form aspires to something like the real-time nature of video yet inevitably fails by its formal properties—in practice, a disembodied, uncanny mimic of human emotion. As gifs, along with emojis, become more streamlined in the applications we use to communicate, the more puppeteer-like these platforms appear, demanding we move in time with the emotional range of the options given.

What must be attended to in a conversation about animatedness and the internet is the fact of animatedness as disproportionately distributed, specifically as produced at the site of racialization. On one hand, one’s humanity is conditional on the capacity to be animated—for bodies to whom humanity is not a given. On the other literal hand, a body animated looks utterly unnatural, puppet-like, revealing the desperation and labor underlying the humanizing project as well as turning “the racial body … into comic spectacle,” to quote again from Ngai.

(And suddenly the voice didn’t go with the hand.)

The internet has quite the sticky track record when it comes to the hyperanimated black body, from the frantic virality of, as BuzzFeed fellow Niela Orr describes, “black trauma remixed for your clicks” to the overrepresentation of black people in reaction gifs used by nonblack users. Though seemingly an aside from an inquiry that looks at online vernacular in a broad sense, to the extent that we recognize black improvisation as critical to how that vernacular develops, we should at least consider how the disproportionate affects of hyperanimative forms might drive the emergence of a new or repurposed kind of expression.

How do you combat online animatedness? You chill out.

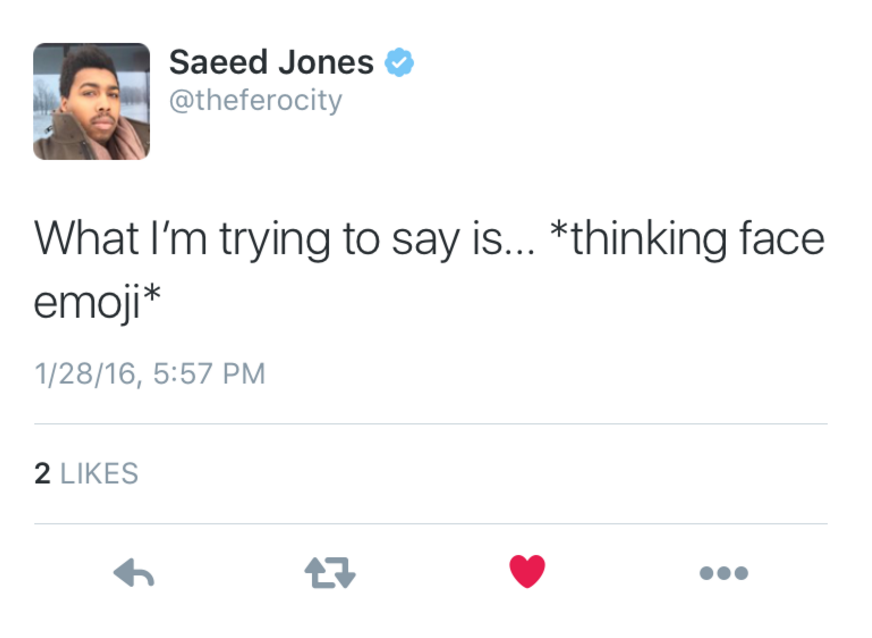

For even as the characters look identical, it would be hard to characterize this (re)emergent language as a backslide into netspeak of old. There is an aestheticized edge, a jadedness that wasn’t there before. Questions have periods. Statements have question marks. Hashtags have gone ironic. Emojis and gifs are as commonplace as ever, yet the simpler emoticons are starting to feel like the more acutely emotional or suggestive image. When punctuation and you-versus-u is no longer a matter of labor saving, there opens up opportunity for new meanings and inflection. The gap between “sure” and “sure” with a period is cosmic.

My suspicion is that fun and play—so crucial to the circulation and enjoyment of idioms—are ever undermining any ability to harness them. Internet vernacular just might be like those really frustrating latex tubules with glittery water inside: The harder you grasp, the more they wiggle, accelerate, break free, and return to the way more exciting place of chaos and nonsense.

This is perhaps best exemplified in what looks like the real next evolution for gifs and emojis: no image at all.

What is dead may never die. Or whatever : )