One day in 1978, chef Michel Bras went for a run and thought it would be a nice to re-create the countryside around him on a plate, as an edible miniature. He had lived all his life in Laguiole, a small village of around 1,200 in southern France, where cattle the color of golden retrievers graze in the hills between farmhouses and 15th century abbeys. The region is one of France’s least densely populated, with an average of three human inhabitants per square kilometer. The fields, however, are overrun with life, sustaining more than 600 kinds of edible plants and vegetables.

Bras, then 32, had grown up working in the kitchen of Lou Muzac, the small hotel restaurant his mother and father ran, serving simple but rich country food — sausages, beefsteaks, trout, potatoes mashed with the dank and nutty local cheese. Instead of escaping to the city to refine his skills, he found his place in the vastness of the landscape.

On his run that day, in the full bloom of summer, the grasses swaying in the warm breeze, tree limbs drooping with fruit, bursts of color in all direction, Bras felt something left unsaid by the roasted meats and fattened potatoes he’d learned to cook under his mother’s tutelage. “It was beautiful, it was rich, it was marvelous,” he told the New York Times in 2009. “I decided to try to translate the fields.”

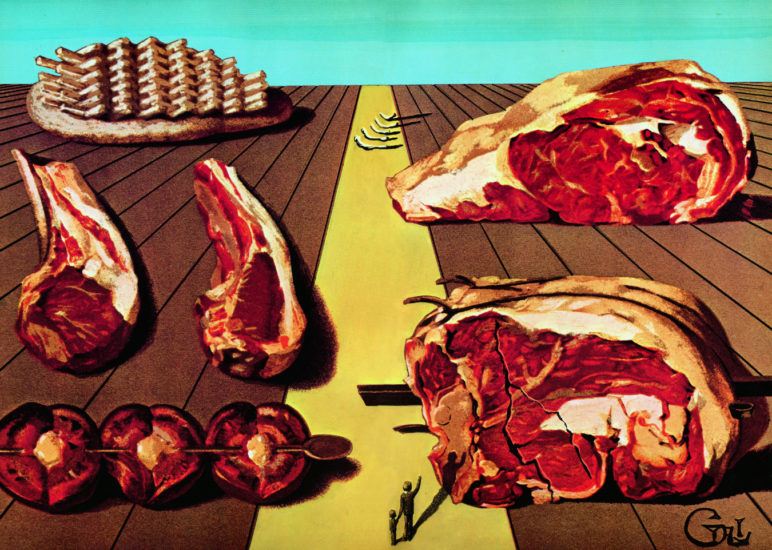

The result was Gargouillou, a dish whimsically described as a salad, in which some 50 or 60 vegetables (depending on what’s in season) are presented on a plate as isolated morsels that present the illusion of a unified whole. Leaves and flowers are spread like moths pinned to a corkboard, while thinly sliced pumpkin, broccoli stem, fennel, and haricot pods crowd the plate’s white space like organ samples in a medical-school anatomy lesson. The colors are effusive, with an after-rain glow; the reds and greens and yellows are bound together with a parsimonious sprinkling of crumbled hazelnuts, or unhulled sesame seeds, or coarsely ground mustard seed, meant to stand in for soil, adding grit to the minerality of the plant matter.

Diners paid to enter an exquisitely desolate emotional context in which they could feel there was nothing left to eat but the landscape

The dish would become one of Bras’s early signatures, helping Lou Muzac win two Michelin stars and transforming the distant village restaurant into a gastronomical landmark. It’s also widely credited with having begun the modern interest in simulated dirt, a modern delicacy sprung from the desire to make the inedible into a high-art staple.

Bras’s invention contained a delicate hint of regression, a faux-violation of one of the simplest rules of the kitchen: cleaned ingredients on clean surfaces. Diners paid to feel the luxury of being beyond such small concessions, to enter an exquisitely desolate emotional context in which they could feel there was nothing left to eat but the landscape.

Cuisine is not just about flavors and preparations, but a way of balancing them on the edge of wastefulness. There is no way to live on the few hundred calories of a salad that takes a full day to prepare. But sustenance is not the point: The sensual pleasures depend on being seen as fleeting and unsustainable. Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin, in his 19th century text on gastronomy, The Physiology of Taste, described this affective melancholy as central to the power of cuisine. The pleasure of the table, he argued, “mingles with all other pleasures, and remains at last to console us for their departure.” Food is both the joyful connective tissue through which one’s senses are unified, and the last remaining constant as those senses slowly degrade over the course of a lifetime. The gritty addition of faux-dirt to Bras’s landscape of vegetal convolutions were meant to evoke not delight but a distant ache of scarcity and hardship, fusing a bucolic melancholy with the meticulous fixations of a modern technician.

Soon a number of chefs were following Bras’s lead, making dirt a gastronomical trope. In the mid-2000s, one of the early signature dishes at René Redzepi’s Noma, in Copenhagen, was Radishes in Soil, a small flower pot filled with a brown-black pseudo-earth topped by three whole radishes treated with an herb emulsion. Another Noma dish, Vegetable Field With Malt Soil and Herbs, takes seasonal baby vegetables, chops them in half, and stands them upright in a layer of Redzepi’s black soil mixture spread across a flat stone. Before it closed, Paul Liebrandt’s Corton, in New York City, offered a vegetable appetizer of individually prepared leaves, herbs, and thinly sliced vegetables over an edible dirt made from black bread crumbs and powdered tomato. David Kinch of Manresa, in Los Gatos, California, makes his dirt from roasted chicory root and dried potatoes. Both Dominique Crenn, of Atelier Crenn, and Daniel Patterson, of Coi, have prepared edible-dirt-based dishes as contestants on Iron Chef America.

Chef Heston Blumenthal of England’s The Fat Duck created his own edible dirt for a BBC series, making not just a single dish but an enormous rectangular garden filled with two different kinds of soil: a topsoil of dried and chopped black olives mixed with grape nuts and pumpkin seeds, and a pasty gray under loam of bread, anchovies, and chopped herbs. Arranged throughout were new potatoes covered in a hard shell of keratin, a compound used to coat pills, which gave them the color and hard texture of small stones. The dish was garnished with edible insects: fried crickets and worms filled with a savory tomato puree.

The final, and perhaps inevitable, escalation emerged in Japan, where pretending to eat dirt gave way to literally doing it. Toshio Tanabe’s Tokyo restaurant Ne Quittez Pas serves a six-course tasting menu with actual dirt in every dish. There’s an amuse bouche of soil and potato starch soup, a risotto flavored with soil, a truffle-stuffed potato ball coated with a thin layer of dirt, and a sweet dirt sorbet for dessert. Tanabe first became acquainted with the taste after deciding to cook with unwashed vegetables and decided to try dirt as a main ingredient in 2005, when he was appearing on a Japanese cooking show and was eager to startle his in-studio diners. Tanabe then developed his own methods for preparing dirt, first by baking it to kill bacteria, than boiling it for 30 minutes to create a broth for use in sauces and jellies. The dirt soup is strained through a cheesecloth to filter out sand and small bits of stone or pebble.

If eating dirt seems unthinkable, it is because of how easy it is to imagine

“It’s very hard to put into words,” Tanabe said of the flavor of dirt, in an interview with Modern Farmer in 2013. “Many people immediately use the word earthy to describe it, but that’s because of their image of soil.”

The absence of language sufficient to accurately describe dirt as a food is part of what drew Tanabe to it. In his way, Tanabe was inverting the logic of nourishment, treating it not as a gesture of fortifying a self in its independence and apparent autonomy but as a means of re-entangling a body with the world. “Man didn’t create the sea or the soil,” he later told the Daily Mail. “They’re simply all part of nature, and in a sense they are alive in their own right. What I’m trying to do is reflect that feeling in food.”

If eating dirt seems unthinkable, it is because of how easy it is to imagine. The practice can be found throughout human history, a reminder of how unstable our idea of food has always been. Food is a taken-for-granted concept that changes radically depending on time, place, and population.

During a year spent in Venezuela in 1799, German naturalist Alexander von Humboldt observed some locals who ate large quantities of dirt and stockpiled dried clay balls as a food source. During the same period in the American South, many slaves ate clay, a practice believed to have been brought over from Africa and which many plantation owners suspected made their slaves indolent. The practice of clay eating has continued, though somewhat furtively, with small bags of kaolin, a white clay that was once the active ingredient in the anti-diarrhea medication Kaopectate and is still sold in some convenience stores and gas stations. On the Tanzanian island of Pemba, pregnant women eat an average of 25 grams of dirt a day, while expectant mothers in Botswana prize dirt from termite mounds. And in Kyrgyzstan, a relatively advanced spectrum of flavor for clays has emerged, separating the desirable (oily, fatty) from the undesirable (salty, sour).

Explanations abound for this enduring phenomenon. On the one hand, it can be seen as a healthy natural instinct to seek out nutritive matter in environments or circumstances where food is scarce. Pregnant women are drawn to dirt, it’s hypothesized, because it can contain calcium, magnesium, zinc, copper, or iron. In other areas, it’s a prudent kind of culinary self-defense, as with Andes Indians who have learned to turn the otherwise toxic Andes potato into a food source by dipping it in mud, blocking the toxins from being absorbed in the digestive tract. In Haiti, the practice of making sun-baked cookies from a mixture of dirt, water, salt, and (if available) butter is used to stave off hunger. In Georgia, some locals used kaolin clay as a hangover cure.

And then there are those who eat dirt for the simple pleasure of its taste and texture. Ruth Anne T. Joiner of Georgia told ABC News that good dirt “has a fresh, natural-feeling taste, like the rain or something.” When ideal, its texture is smooth, “like a piece of candy,” which can create a powerful craving. An anonymous woman, cited in Gerald N. Callahan’s Lousy Sex: Creating Self in an Infectious World, reported eating between 15 and 16 pounds of dirt a week, something she claimed to do primarily “for the great taste and the way it melts in my mouth. Dare I say that it’s even better than sex (and believe me I have a great sex life).” In a 2012 episode of My Strange Addiction, a compulsive dirt eater said, “I like the feeling of it. It’s cold and wet, it is like finding a buried treasure to me … It just tastes enriching and fulfilling.”

Beginning in the 19th century, these sorts of responses had already been safely shuttled outside the limits of normal human behavior and grouped under the pathological umbrella of pica, an eating disorder broadly defined as the consumption of “nonnutritive foods.” In 2000, a pica workshop organized by the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, a public health agency overseen by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, further refined the diagnostic criteria for soil pica to anything over 500 milligrams of dirt or clay in a day, the equivalent of a tenth of a teaspoon. Further supporting the idea of dirt-eating as dysfunction, some researchers and physicians warn that dirt can carry infectious bacteria and spores, cause ulcers or tissue ruptures in the digestive tract because of its abrasive quality, or block the absorption of nutrients and potentially lead to anemia, not to mention grind down one’s teeth and cause potential cracks.

Yet the way dirt eating addresses our vulnerabilities may be what gives the practice its power. Nearly half of children between 18 months and 36 months attempt to ingest non-food, and more or less every child uses their mouth as a primary organ for palpating the world, gnawing and biting to absorb textural and dimensional information before gaining coordinated control of hands and fingers. Immunologist Mary Ruebush has argued a similar process of curiosity and experimentation is at work on the microscopic level as well. In her book Why Dirt Is Good, Ruebush argues, “What a child is doing when he puts things in his mouth is allowing his immune response to explore his environment. Not only does this allow for ‘practice’ of immune responses, which will be necessary for protection, but it also plays a critical role in teaching the immature immune response what is best ignored.”

Along the spectrum of good taste and the lack of it, dirt presents the uncanny illusion of common ground in the middle, while offering something emotionally raw to the well-fed to help them pass the time

In a 2003 study of dirt eating published in the CDC’s Emerging Infectious Diseases journal, Gerald N. Callahan described the habit of part of the long co-dependency between human life and bacteria, a kind of evolutionary “waltz”: “Bacteria outnumber, outweigh, out-travel, and outevolve us. That bacteria cause so many human diseases is not astounding. It is astounding that so few bacteria cause human disease … Billions of years of confrontation rather than luck were likely our benefactor. Through those confrontations and those eons, nearly all of us learned to coexist peacefully. Neither humans nor microorganisms benefit from fully destroying the other.”

In transforming cooking from a staple to an art, cuisine has exploited the microbial, claimed its positive consequences as proof of the virtues of the fine dining classes. At the same time, hunger itself has been pathologized, studied as a medical mystery that threatens to undermine one’s mental fitness and the moral clarity that depends on it. An experiment from the University of Minnesota in 1950 sought to investigate the long-term effects of malnutrition by reducing by half the caloric intake of 36 subjects, all men, for six months. Every participant developed eating disorders after completing the experiment; one fell into a deep depression after having his diet restored to pre-experiment levels and cut off three of his fingers.

Along the spectrum of good taste and the lack of it, dirt presents the uncanny illusion of common ground in the middle, providing the hungry a compulsive and sensual experience while offering something emotionally raw to the well-fed to help them pass the time. The evolutionary arc of gastronomy has begun to trace a path away from the chimerical simulations of new flavor in unknown syntheses, and toward becoming a simulation of food, something that the predilection for eating dirt proves isn’t limited by class or culture. We all take pleasure in fakes and mimicries, both for how they act on our bodies and for how our bodies rise to fill in the gaps left between the simulation and the thing itself. The unconscious joy of fraudulence is in its dependence on us as participants; accepting the deceptive confusion is the price we pay to maintain the illusion that our tastes, feelings, or reactions are somehow central.

As the notion of cuisine developed, food was seen more as a medium to connect our bodies to the landscapes they inhabited, something that had meaning only so long as it could point toward something outside itself. The oenophile’s fixation on terroir — a superstitious practice of tracing the character and quality of soil a grape has been grown in through to the wine made from it — companies like Taste of Place have organized soil tastings. Participants are guided through a tasting menu of fresh vegetables paired with aromatic tinctures made from the soil each particular vegetable was grown in. This is supposed to enhance one’s attentiveness not just to flavor profiles but to biological dependences not immediately obvious to the palate. One consumes the illusion of ecological symbiosis, as if humans had wriggled our way out of our own ecosystems at some point in the recent past, as if the idea of living in pursuit of conceptual clarity had liberated us from having to bother with the mulch of inconclusive intermediaries.

Behind Bras’s visionary complications of simple country food was an instinct for trash, both as an expression of humble country-folk austerity (“We ate in order to not starve, so my approach toward the product is mostly to avoid waste,” he has said) and as a high-wire act of gastronomic alchemy. Asked in 2011 what his favorite foods are, Bras listed a few ingredients often viewed as nonfood: “I love the broccoli stem that most people throw away,” he said, and he included the seeds from an apple core, for their phenomenal “palette of expression” and because “that’s the first thing you find in the garbage.”

There is more than metaphysics in this. Beneath all forms of culinary invention and scrounging through the filth beneath our feet is another superstition about real hunger — not the irritable inconvenience that sours moods in the afternoon or even the gathering weakness that turns our brains into thickening concrete, but something bad and beastly. Following Brillat-Savarin’s hint, the gastronomic rediscovery of dirt is a prelapsarian shudder of the diner’s imagination, an acknowledgement that the pursuit of authenticity always points toward a desire for ego-loss. In dirt and trash, the burdensome permanence of identity — class, career, sex, opinion — can be imagined as insubstantial, composed of constituent substances that can be decomposed back into nothing other than matter.

In the rediscovery of soil itself, culinary art has begun to point back to the earth not as “earthy” flavor or even a simulation of nourishment in the affective warmth of beurre blancs and beer-fattened loins, but for its symbolic link to the soil’s microbial richness. Nutritional fantasies of living well or long by virtue of eating and optimally absorbing whatever ingredients are on trend — fantasies of separating from and surpassing one’s environment — have been redirected toward eating imitations of a sense of dependency.

We begin to consume ourselves, not as continuously improving, perfectible beings but as constituents in a larger ecosystem and hosts of an ultimately unknowable inner ecosystem that we access only indirectly, as a matter of faith. Trading a calibrated diet of mixed vitamins and portion-controlled meals for a mouthful of dirt isn’t a deviation from the modern injunction to master one’s body but a desire to feel from the inside out how flexible and dynamic its systems can be, something that was gradually lost in the rush toward optimization. When we take nootropic supplements or gorge on broccoli sprouts and salted garlic in the belief that they can ward away the treasonous specters of cancer or heart disease, it’s not just because we’ve been told it will help but because waiting for the uncertain fruits of self-improvement to appear has the flavor of helplessness, which becomes a delicacy in its own right.

Coded into gastronomical technologies and the magical transformations that evolution has performed on the human digestive tract is an inherent danger: a subtle but precarious detachment from the matter that surrounds us. Beneath the new experiments to produce edible matter from tree bark or processed human excrement is a narrowing dread that these aren’t just utopian gambits. Haute cuisine once valued detached identities and individualism over the shared affective response to simple, straightforward ingredients. Now it wants to cultivate the reaction we have to those direct flavors not in shared social experience but in the inaccessible reaches of our biome: a microscopic response and adaptation, a body reminding its mind that it is still alive, as the landscape inside dreams of swallowing the landscape without.