The first one I saw was the girl in Dutch painter Johannes Vermeer’s Girl With a Pearl Earring. Looking over her shoulder, she stares off into the distance and then shifts her gaze to hold mine for a second. She looks away again, and the left-hand corner of her mouth inadvertently twitches with the briefest of smiles. In this simulation, her eyes are shiny gray and bulbous, like a dead fish. These movements are a set sequence of events, a technological update to a centuries-old image.

Last but not least: “Das Mädchen mit dem Perlenohrgehänge” von Vermeer, in animiert. #DeepNostalgia @MyHeritage

Ein bewegendes Tool! 😉 pic.twitter.com/eLwRKMYQCQ

— Bruckner 0 (@Lustbarkeit) March 1, 2021

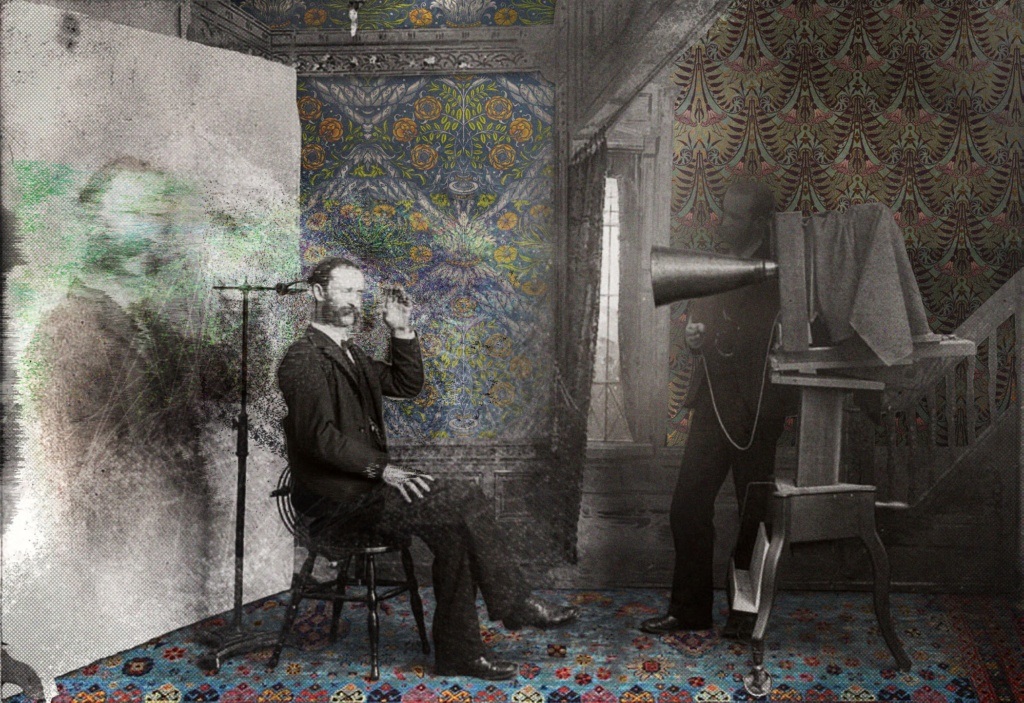

In late February, the Tel Aviv–based online genealogy platform MyHeritage released a feature with the trademarked name Deep Nostalgia: a machine-learning-powered technology that animates uploaded images with a programmed series of facial gestures and movements that users can apply to any uploaded image. In the days since its release, Deep Nostalgia went viral: As of March 4, millions of faces have been animated, with thousands of images animated per minute. By this point, I’ve seen dozens of these animated images — people’s relatives, famous portraits, historical figures. Nero, Shakespeare, Nosferatu, even a photograph of a statue of Cicero. Pee-wee Herman applied the technology to a childhood photograph of himself: “Creepy?! Or cool?!” he asked.

Much of the reaction to Deep Nostalgia has been encompassed by those two choices, as if they naturally defined the continuum of opinion suitable for any new technology. The polarized response has helped its popularity, as though using it were to participate in a cultural debate about something new and surprising. But if so, the debate is hardly new: The internet was literally built on the popularity of altered images, for what is a meme but image manipulation, transposition, juxtaposition? It’s been almost four years already since the Tom Cruise deepfake had us all rattled (though now it has been revived again on TikTok). It’s well past time to simply be “uncomfortable” with these kinds of images. They require a deeper consideration of the stakes. And so while I’m surprised by the surprise, I’m alarmed by the atmosphere that continues to make these media technologies both possible and desired.

Part of the particular unease evoked by Deep Nostalgia stems from how we’ve been primed for it by tech media and sci-fi, as in the Black Mirror episode that explores the logical conclusion for this sort of technology: the reanimation of lost loved ones in the form of a personality-powered bot and ultimately as a physical, synthetic controllable re-creation. But such reactions and expectations for image-manipulation apps, features, and bots ignore more urgent concerns that are an immediate matter of life and death, especially for those of us who unequally experience the destructive outcomes of technology.

The focus on how unnerving the Deep Nostalgia images are distracts from the deeper and more urgent issues they reflect

To participate in Deep Nostalgia, a user is required to upload photographs, and this sourcing of images — without the need for explicit consent of the person in the image — expands the application of AI to develop increasingly sophisticated surveillance technologies. Deep Nostalgia is touted for its capability of animating family archives, inviting people to “experience family history like never before!” and manufacture memories of relatives it would have been impossible for them to meet in person. It taps into the curiosity we have about the people we come from, our tendency to make their lives legendary in our imaginations. But though this gimmick purports to facilitate an engagement with history, its confluence of facial recognition and machine learning seems to make commentators overlook these technologies’ conjugation from surveillance and tracking software. The focus on how unnerving the Deep Nostalgia images are distracts from the deeper and more urgent issues they reflect — creepy is a feeling. In the material world, these image manipulation technologies are implicated in the surveillance, criminalization, and policing technologies, which have uneven consequences.

By this point, we should be used to this technological haunting of dead people’s images. Hologram tours by dead artists have been going on for years. The late Carrie Fisher’s appeared in a new Star Wars movie by blending archival footage with the digitally altered performance of a live actor. And whole “people” have been constructed using technology. Almost 20 years ago, in the movie S1M0NE, Canadian actress Rachel Roberts played Simone, a computer-generated Hollywood actress. The producers had initially wanted to program a CGI character for the main role, but the Screen Actors Guild opposed the move, claiming it would jeopardize the careers of human actors. Digital effects were added to Roberts’s scenes to make the character look more synthetic. While acting roles haven’t been affected to the anticipated degree, we do have virtual influencers. This suggests how the impact of the technology can be redistributed.

The reaction from those repulsed by the animated images often refers to them as “creepy” and “uncanny.” Uncanny is how we refer to lifelike robots, when there’s a material attempt at duplicating humanity. But this is not what’s happening here: The implications of the technology are much more than an attempt at replication. Seeing facial expressions that we know never happened prompts a disturbing reconsideration of how we establish or determine humanity and integrate personality through the agency of faces. With the Tom Cruise deepfake, the actor’s face was spliced onto the body of an impersonator, someone who was already familiar with Cruise’s mannerisms. But as the technology develops from its initial and primitive filter roots, its applications become unholy rather than uncanny, digital Frankensteins mashing up body parts with faces, like the splicing of Steve Harvey’s face onto Megan Thee Stallion’s body.

Kept away from those we love, unable to mourn, this technology returns a sense of control by allowing us to imagine and re-create the moments we were denied

Some people are moved by seeing Deep Nostalgia’s lifelike gestures on flattened photographs; others are troubled by it. I understand what people find unnerving here: When you know someone has passed, it’s uncomfortable to think of their image being manipulated in this way after their death. And by extension, it’s uncomfortable to think of your own image puppeteered in this way, whether you are dead or not. The applications of the technology do raise questions of consent, rights, and ownership of our likeness. It’s one thing to animate a 17th century oil painting; it’s another to animate images of actual people who once lived. What’s most unnerving is that all that’s required is having an image — no ownership rights or permissions are required to upload them to Deep Nostalgia and allow for the representation of people through gestures they never intended or meant.

The popularity of Deep Nostalgia is hand in glove with our current moment. It’s a been a year of the coronavirus pandemic and its upheavals, restrictions and anxieties — a whole year of counting death and limiting life. It’s been a year of having our grief disrupted: We can’t attend funerals, we can’t gather at bedsides or congregate at services. We can’t even hug other people or say goodbye or have closure. And so this technology offers us solace in nostalgia. For those we’ve never met, it allows us to imagine what they would be like alive, adds a sliver of dimensionality that informs our manufactured memories. And more unnervingly, for those recently deceased, it produces additional content for our consumption, the possibility of placing our own consent to their likeness.

This is a commentary on our own helplessness: kept far away from those we love, unable to mourn, perhaps this technology returns to us a sense of control by allowing us to imagine and re-create the moments we were denied. For now, Deep Nostalgia generates a limited sequence of actions, but it feels inevitable that we’ll reach a point where we’ll have even more control in designing fantasy scenarios and more reason to link hope and desire to the capacity to manipulate people’s likenesses and actions in undetectable ways.

On my Twitter timeline, I’ve come across at least three different Deep Nostalgia–manipulated images of the Black abolitionist Frederick Douglass, who died in 1895. Douglass had a very deliberate relationship with his image: During his lifetime, he was the most photographed man in America. His approach was a precursor to what British-Ghanaian filmmaker John Akomfrah describes as the “utopian yearnings” of image technologies. Douglass delivered several talks on the subject of photography, and in his lecture “On Pictures” he writes:

Byron says that a man looks dead when his Biography is written. The same is even more true when his picture is taken. There is even something statue-like about such men. See them when or where you will, and unless they are totally off guard, they are either serenely sitting or rigidly standing in what they fancy their best attitude for a picture.

Douglass had determined that his “best attitude for a picture” was a calm and serious face, unsmiling. The Deep Nostalgia animation of one of his portraits — that programmed inadvertent left-hand-corner-of-the-mouth twitch — undermines Douglass’s agency in determining that photographs of him would present him as strong, dignified, and serious. Douglass was intentional in employing photographic technologies to visually challenge the assumed inferiority of slaves. He understood that photographic images could be a powerful tool and sought out photographers and sat for photographs whenever he could.

Douglass had a very deliberate relationship with his image: He had determined that his “best attitude for a picture” was a calm and serious face, unsmiling

His reanimation through Deep Nostalgia is thus concerning. Circulating manipulated images of a Black man — even one who has been dead for over a century — in defiance of his clearly stated desires evokes recent situations when the deaths of Black people have been circulated. Deep Nostalgia is marketed as a fun tool to interact with the long-forgotten past, but its appearance at this moment in pandemic times braids it into the emerging technologies we will develop around mourning, from attending Zoom funerals to grieving through seeking closure denied with apps like AI-driven apps.

I’ve written before that when human-computer interaction design — like social media networks, and health apps — considers the death of the user, it also needs to contend with Black life. Deep Nostalgia is no different. The deaths of Black people as they appear online reflect the lives of Black people everywhere. When media technology does away with notions of privacy and permission, it is imbricated in how surveillance is targeted, how consent is abrogated, how rights are contested, and property is appropriated.

The implications of technology aren’t distributed evenly, and if these concerns aren’t confronted and addressed now, the inevitable evolution of machine-learning technologies like Deep Nostalgia will distribute those uneven effects exponentially. Not only are they building on technologies that are dependent on biased data sets and that normalize surveillance practices and the carceral state; they also allow existing power imbalances to be exploited and further widened.

The synchronicity of having an AI-powered image manipulation technology end up renditions of several images of Frederick Douglass, the most photographed man of his time can’t be coincidental. But what it ultimately means is not fixed: Deep Nostalgia markets a celebration of the past, seemingly in spite of the wishes of the past. I read the appearance of Douglass’s animated face as a harbinger of the disproportionately harmful effects of these technologies on Black people, and yet I hope that by making his image more available, the impact of his legacy will outlast these technologies.