Every day, without our realizing it, the images, text and other data we post for our own purposes are scrutinized and collected by countless outside eyes for purposes we are unaware of and would often not consent to if we were aware of them. This process of collection and analysis is known as “data scraping” or “web scraping.” Though scraping overrides people’s will without scruple and enlists their contributions in initiatives they would reject, most people in the tech industry take scraping for granted as a ubiquitous, unavoidable part of the everyday operation of web technology. Some claim that it can be harnessed as a force for good, even as it has empowered data brokers, surveillance tech merchants, and forms of automation and algorithmic administration. Is it defensible? Is it necessary? Should it be outlawed altogether, or allowed without any regulation at all?

Scraping is related to but distinct from “web crawling,” which Google and Archive.org, for example, use to gather the contents of web pages. Whereas web crawling usually implies a known and anticipated process of indexing the content of sites so that people can find them, and which can be blocked by platforms, “scraping” aims to extract data from pages for further processing, with proprietary aims in mind that may have nothing to do with the information’s original context, typically in such a way that it cannot be blocked by users or platforms. Somewhat like eavesdropping or its online equivalent, key logging, “scraping” connotes a partly or entirely clandestine form of data collection. Implicit in the basic idea of scraping is that data is being put into a different form and then turned to different uses from the ones that user or a site’s administrator intends. This secondary use or analysis distinguishes scraping from the closely related activity of hacking a site to take (or, far more often, copy) data.

Regardless of its uses, scraping can sound like intrusive hacking — because it is

The technique is commonly used in the financial industry, for uses as apparently benign as tracking mentions of a company’s stock in social media, or tracking mentions of a company’s corporate actions and their reception. It is commonly used to track aspects of human resource management, including how many people are changing jobs or expressing interest in doing so. Some data brokers make intensive use of this process, in some cases apparently building their whole products on data obtained through the method.

The data broker industry is clouded in mystery, not only taking data from users without their permission, let alone their knowledge, but also refusing to make clear to their customers the sources of their data. The practices of the industry have long been questioned. Investigative journalist Julia Angwin co-authored a 2010 article in the Wall Street Journal drawing attention to data brokers and their use of scraping; at the time she found that the media research firm Nielsen was gathering highly personal information about the mental health conditions of people who posted to discussion boards, a practice Nielsen says it has discontinued. Meanwhile, last week, Senators Elizabeth Warren, Ron Wyden and others have introduced a bill seeking to block data brokers who may be collecting data, including scraped third-party data, from users “researching reproductive health care online, updating a period-tracking app, or bringing a phone to the doctor’s office,” all of great concern given the U.S. Supreme Court’s imminent threat to Roe v Wade.

Yet scraping is not just used to produce financial profit or directly harm vulnerable people. Academic researchers, journalists, and activists also scrape data to analyze and better understand the practices of institutions and classes of people, like say, landlords or white supremacists, or to limn the nature and extent of disinformation networks. Some of these uses are so benign it is hard to imagine preventing them: the New York Times, like other newspapers, scrapes election results from local governments and newspapers in order to gather national data; the Times publishes the code for its scraper on GitHub. Perhaps slightly more controversial — in that they turn data against the uses its creators intend — are some of University of Washington researcher Kate Starbird’s many investigations of disinformation and the far right, which sometimes use scraping especially to gather and analyze data about the connections between far-right disinformation promoters and the sites that spread disinfo. Data journalism site The Markup uses scraping methods for its invaluable work, including the “Citizen Browser” application it developed, installed by more than 1,000 paid participants, to gather and analyze data on Facebook’s advertising practices that the platform does not make publicly available.

Regardless of the uses to which it is put, to most of us, scraping can sound like a kind of intrusive hacking — because it is. Yet scraping is widely conducted for range of purposes and is seen as a legitimate practice by many in the tech industry. Much more of the web operates via scraping than many of us realize. This poses problems for thinking about how to regulate, legislate, and even build web-based technology. To block such third-party access requires surprisingly complicated mechanisms for distinguishing between ordinary users and scrapers. While some forms can be programmatically blocked — there are many commercial and open source software tools available that web providers can install to prevent scraping, and familiar features like Captchas exist in part to block unwanted scraping — scrapers are always building more sophisticated tools, setting off an arms race between scrapers and blocking technology familiar from efforts to fight spam and perform content moderation.

Scrapers often claim authorization is superfluous because the data they access is nominally “public.” Hoan Ton-That, the CEO of Clearview AI — a surveillance tech company whose main product is based on scraped images — routinely justifies the company’s practices by stating that it collects “only public data from the open internet and comply with all standards of privacy and law.” According to Kashmir Hill’s New York Times report in 2020, the company collected “images of people’s faces from across the internet, such as employment sites, news sites, educational sites, and social networks including Facebook, YouTube, Twitter, Instagram and even Venmo” despite the fact that “representatives of those companies said their policies prohibit such scraping, and Twitter said it explicitly banned use of its data for facial recognition.”

Scraping disregards contextual integrity and asserts a right to inhale entire data sets and process them

The norms surrounding that kind of public-ness have often been debated, particularly with respect to Twitter, where there has been some controversy over whether journalistic outlets can quote a user’s public tweets without their consent. Privacy scholar Helen Nissenbaum refers to this problem when she writes about “contextual integrity”: that users tend to assume that publicity should go only as far as they contexts they are able to anticipate, despite tools that make it easy for interlopers to do much more.

Scraping disregards claims of contextual integrity and instead asserts the right to inhale entire data sets and process them for the use of others. That is, scrapers assert that data made public in its user-facing form is also public in something like its algorithmic form: Not only did the user agree to publish their tweets, but they also agreed to publish all the inferences, post-processing, and analysis that data services might make based on their tweets, which typically go well beyond what most users understand.

As I put it in 2018, we don’t know what “personal data” means. In other words, social media users have a limited understanding of the uses to which data generated by them and about them on platforms can be put. It’s natural to believe that posting a picture or tweet to a public feed means simply that some other user might look at it. We may or may not know or approve of that other viewer, but that seems like the end of the story. Thus users may assume that the content and the form of their posts remain intact after they post it. But they don’t consider how that those posts turn into what specialists call derived and inferred data, two categories that facilitate further algorithmic processing, including AI techniques like machine learning.

Using a variety of techniques, data that appears to be about one thing can be made to reveal many other things. Fully “anonymized” location data on a phone might turn out to be easily associated with the only person who lives at one of the addresses at which the phone is often found. Buying some products and not others reveals a great deal about the makeup of one’s household. And in more extreme cases, which are also the ones on which the data broker industry thrives, apparently innocuous data like the music a person likes can turn out to reveal their religious backgrounds and political affiliations (exactly what Cambridge Analytica is said to have done before it was put out of business). It is fair to say that many people might willingly share the fact that they like BTS, while being entirely unaware that they are also sharing their voting behavior.

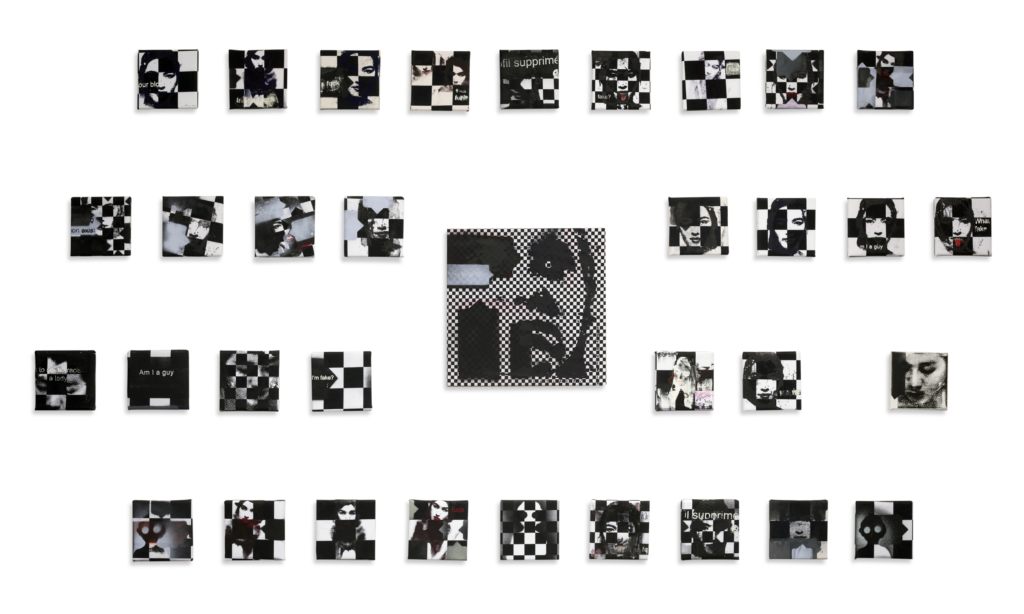

This is the essence of the violence implicit in the choice of the term scraping to describe this form of data collection: the process of dislodging data from one context and forcing it into another, where we no longer control in any way how that data is used, what meanings are inferred from it, whether it is “accurate” to begin with, and whether its extended uses are accurate. Scrapers’ indifference to consent means not only that their methods are ethically dubious but also that their data and results are tainted and conceptually unreliable. Any application derived from scraped data carries that stigma.

The scraping practices of Clearview AI are now coming under intense scrutiny from lawmakers and digital rights advocates, and the arguments presented by both its advocates and its critics help illustrate how many common intuitions about “privacy” and “free speech” do not always serve us well when applied to novel digital contexts.

The most prominent court case to involve scraping so far involves a small data services company called hiQ that sued LinkedIn over the ability to scrape data from LinkedIn’s platform. According to court filings, LinkedIn uses a variety of means to protect its users from scraping and related techniques, including a “Do Not Broadcast” option used by more than 20 percent of all active users, a “robots.txt” file that prevents scraping by many entities (although it allows the Google search engine to web crawl), and technical means (including ones it calls Quicksand and Sentinel) that detect and throttle “non-human activity indicative of scraping.” Despite these protections, hiQ managed to offer its clients two services based on scraping LinkedIn data, including one that “purports to identify employees at the greatest risk of being recruited away” and another that helps “employers identify skill gaps in the workforces so they can offer internal training in those areas.” In 2017, LinkedIn sent hiQ a cease-and-desist letter, claiming that its operations violated LinkedIn’s terms of service and a number of California state and U.S. federal laws.

The 2019 Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ruling — affirmed in April 2022 — ordered LinkedIn to allow hiQ to continue its scraping business. It stated that “there is little evidence that LinkedIn users who choose to make their profiles public actually maintain an expectation of privacy with respect to the information that they post publicly,” and that “even if some users retain some privacy interests in their information notwithstanding their decision to make their profiles public, we cannot, on the record before us, conclude that those interests … are significant enough to outweigh hiQ’s interest in continuing its business.”

Perhaps surprisingly, this decision was celebrated by civil liberties and digital rights advocates, portrayed as a victory for “internet freedom” and “the open web” because some of these groups affirm a right to scrape, seizing on what they regard as socially beneficial use cases, despite that fact that cases like hiQ’s that seem to abuse privacy and consent are far more prevalent. If you thought that, for example, the Electronic Frontier Foundation’s aim of “defending your rights in the digital age” would mean rejecting a rigid “public is public stance,” you’d be wrong: It celebrated hiQ’s victory, mostly because it undermines the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, a favorite target of cyberlibertarians who believe the rarely used law criminalizes ordinary and inoffensive conduct (the Department of Justice has recently issued guidance clarifying that it will not prosecute such conduct), but also because it champions the right to analyze “public” data over the right to protect it.

Scrapers’ indifference to consent means their data and results are conceptually unreliable

Other organizations have situationally taken a similar stance, in service of different politics. Just a month before the most recent hiQ ruling, the ACLU and NAACP’s South Carolina chapter sued the South Carolina Court Administration over its prohibition of scraping a county-by-county database of legal filings, claiming “a protected First Amendment right to access and record these public court records for these purposes.” Of course, the NAACP’s claim that it needs access to those records to challenge the eviction of renters from their homes is compelling. As the plaintiffs put it, “scraping is widely employed by researchers, reporters, and watchdog groups to capture and evaluate population-level data on websites which would be impracticable to collect using manual methods.”

Yet as the hiQ case shows, these same arguments are used not just by social justice advocates but also by companies whose products are built on the invasion of privacy in the face of relatively explicit user requests to stop. In both the ACLU/NAACP lawsuit and some coverage of hiQ, activists present it as given that the “researchers” and “academics” they represent intend only “good” uses for scraping technology. But the idea that they form a separate class of good-faith operators whose needs for scraped data are entirely different from those of corporate privacy invaders needs much more scrutiny. Despite the express anti-racist purpose to which, in the ACLU/NAACP filing’s no doubt honest assertion, the scraped data will be put, it’s hard to see how their legal arguments would not apply just as fully to one of the data brokers who provide “tenant screening” to landlords, and who may well see a simple filing for eviction — whether justified and eventually adjudicated in the tenant’s favor or not — as a red flag.

Even a moment’s reflection will reveal that, in fact, academics and researchers themselves don’t all agree about much of anything. Further, many academic and nonprofit bodies work very hard to support business interests, from megacorporations like Facebook/Meta to small startups. Cambridge Analytica notoriously built itself on the work of Stanford business professor Michal Kosinski, who has a troubling history of developing invasive or controversial techniques in academic research. “Most of my studies have been intended as warnings,” he has said, while nonetheless describing in great how to do what he purportedly warns against doing, including determining political orientation from facial recognition, inferring the “personality of countries,” and claiming facial recognition can be used to infer sexual orientation. It is hard to read tech journalist Issie Lapowsky’s 2018 story without concluding that academic research using scraped data made possible Cambridge Analytica’s behavioral modification product. Many other would-be behavioral-modification providers — possibly including Cambridge Analytica’s shadowy successor companies, and data mining companies like Peter Thiel’s Palantir — continue to operate all over the world with relative impunity. Efforts to understand and enumerate, let alone regulate, these companies have proved very difficult.

These contradictory tendencies came to a head in a suit filed by the ACLU against Clearview AI for violating user privacy by scraping photos. The suit, recently settled, was partly based on the Illinois Biometric Information Privacy Act, which requires consent for faceprinting Illinois citizens along with other forms of biometric collection. Notably, in states without a similar law, the ACLU and other digital rights advocates have taken different positions. In the South Carolina case, for instance, the ACLU does not mention consent as an important consideration and generally argues against prohibitions of the sort of scraping that would almost certainly create the same kinds of issues as the Illinois case. In the hiQ case, the ACLU was among the many groups celebrating the “freedom” of commercial data harvesters to violate the express wishes of ordinary people.

Clearview has argued that its product cannot be regulated because of First Amendment protection, an argument rejected by most courts that have heard it and criticized by the ACLU itself. But it has been pushed by prominent First Amendment attorneys, including Floyd Abrams, who in Citizens United joined the ACLU in arguing that limits on campaign spending were unconstitutional prohibitions on speech. Clearview’s position was also supported by some of the right-leaning legal thought leaders like the libertarians at Reason who deploy the First Amendment as a shield against tech regulation. As Mary Ann Franks demonstrates in her book The Cult of the Constitution, the ACLU has often joined with EFF and other “digital rights” organizations to shape and oppose privacy laws in ways that seem favorable to the interests of invasive companies.

In its settlement announcement, the ACLU celebrated that “Clearview is permanently banned, nationwide, from making its faceprint database available to most businesses and other private entities.” Yet Clearview and its advocates read the still pending settlement differently. Abrams claimed, as this Guardian story reports, that it “does not require any material change in the company’s business model or bar it from any conduct in which it engages at the present time.”

That both sides declare clear and unambiguous victory while disagreeing almost entirely about what the victory means is not unusual in tech regulation and litigation. It shows that our basic (largely pre-digital) intuitions about fundamental ideas like “private,” “public,” “consent,” and “expression” do not always serve us well when we attempt to apply them to digital technology. Perhaps entirely new concepts are needed, or new ways to stretch our old concepts to the new environment.

Not just industry itself, but some of the digital rights groups that pursue multiple policy goals frequently find themselves on both sides of promoting and criticizing scraping. In the ACLU’s case, it stems from being a national organization with many divisions and many state-level chapters. But it also points to a problem that has long frustrated at least a minority of academics: how the ACLU, EFF, and others like Fight for the Future, and quasi-academic organizations like Data & Society, the Berkman Center, and the MIT Media Lab establish themselves as the go-to sources to protect “human rights in the digital age.” Some of these organizations — indeed most of them — have murky relationships with technology developers and technology corporations (EFF, for example, lists “innovation” as one of its core values in its tagline, more typically a point of emphasis for corporate lobbies than civil rights organizations), and they frequently engage in dismissive conduct toward people outside their organizations, especially those whose opinions don’t line up with their own carefully crafted position statements.

Is scraping abuse? Some cases, like Clearview AI, certainly make it seem so, but as a general principle I don’t think a fair observer can really answer that question. Our knowledge as users and observers of digital media is far too limited. We need robust regulatory regimes of the types so far implemented largely in the European Union even to start to judge the ethics and politics of scraping: laws and regulations that require data brokers and scrapers to make clear what they are doing and perhaps even register their businesses, as Vermont has tried to make them do. We need better typologies of scraping and scraping-like activities so that we can develop richer accounts of consent to share data, and of analysis and processing of that data. Digital rights advocates need to leave much more space for consumers, academics, and others to come up to speed on the various ways that our data is used and to weigh in on what does and does not conform to our expectations of privacy, publicity, and dignity.

Liz O’Sullivan contributed to an early version of this piece.