At the point in the day where any act of willful selection starts to feel like an impossible exertion, I turn on the automatic drip of video content. For better or for worse, what usually comes out first is footage of people playing video games — the face of the player overlaid in a neat box in the corner, bellowing in frustration as their avatar falls to enemy gunfire, while messages from the channel’s chat blitz down the right side of the screen. Sometimes I get doses of expert analysis: a heavy metal guitarist watches a video of a band’s performance, pausing occasionally to offer color commentary. Switching platforms, I watch a man deliver “iced coffee reviews” in a deadpan patter, his dim bedroom juxtaposed with a sunny kitchen where two disembodied hands are drizzling caramel and frothing milk. This is numbing stuff, ideal for an evening of lite binging in a hypnagogic state of half-attention. It is content that demands no response from me — not simply because it is non-narrative and ambiently pleasing, but because any response I’m likely to have is already incorporated into the content itself. The content arrives pre-metabolized, pre-experienced; all I have to do is absorb it.

This is numbing stuff, ideal for a hypnagogic state of half-attention. It is content that demands no response from me

No doubt the history of pre-metabolized content stretches back roughly as far as we have records of human expression. Its greatest hits would include: the Greek chorus; medieval manuscripts where an outer ring of commentary threatens to swallow the text itself; scribbled marginalia throughout the ages; the phony scholarly apparatus that pads certain Gothic novels; frame narratives of all kinds; faux live music recordings embellished with edited-in applause; the sitcom laugh track; the daytime talk show audience. Still, these were discrete forms with clear boundaries. Across today’s online mediascape, things are far more diffuse. Spend enough time in its swirl, and you may eventually start to suspect that today, all content is reaction content.

The reaction video was perhaps the first genuinely new and enduring genre to emerge from the primordial soup of early YouTube. Once, some critics thought that video sharing platforms would turn the internet into a nonstop talent show. All the web a cafetorium, and we the audience, pulling up a folding chair. At a touch, we could call up a whole gamut of amateur performances, from the spectacular to the cringe-inducing, in comedy, drama, music, dance. Or else, it seemed to others, video sharing could finally provide the perfect outlet for good-old-fashioned voyeurism. Video blogs and live webcam feeds promised to make the faces, the living rooms, the inner lives of perfect strangers available to us. In the 2000s, all this seemed like the logical culmination of a long progression of reality media, from cinéma vérité and socialist documentary film to reality television and mumblecore: Finally we arrived at the totally unstaged situation, the authentic spontaneity of people as they really are. The thrill of early user-generated video seemed to be either the joy of discovering amateur talent, or else the frisson of access, of spying on unguarded strangers through lighted windows, in grainy silhouette.

The earliest reaction videos had something of a slice-of-life character. A shaky handheld camera documents a family watching the proto-viral-video “Scarlet Takes a Tumble” in a living room, one of their number collapsed over himself in outsize hysterics. A man films a scene from his hike: a double rainbow arcing over the tree line as the enraptured hiker sobs in wonderment. And yet it was also hard to escape the feeling that these displays were performances — not in the sense that they were disingenuous, but because they were undeniably virtuosic. In today’s internet-speak, these were especially well calibrated fits of shaking, crying, throwing up — this last quite literally, in the case of the reaction videos to the infamous gross-out porn clip “2 Girls 1 Cup” that started to proliferate around 2007. These early reactors, nearly all reluctant or unwitting viral-video stars, had already mastered the legible displays of feeling that social media platforms would come to elicit from us with mounting urgency in the years to follow. Part documentary, but decidedly non-narrative; part performance, but not tied to any traditional talent, and all hydraulically compressed emotion: This was extreme reacting.

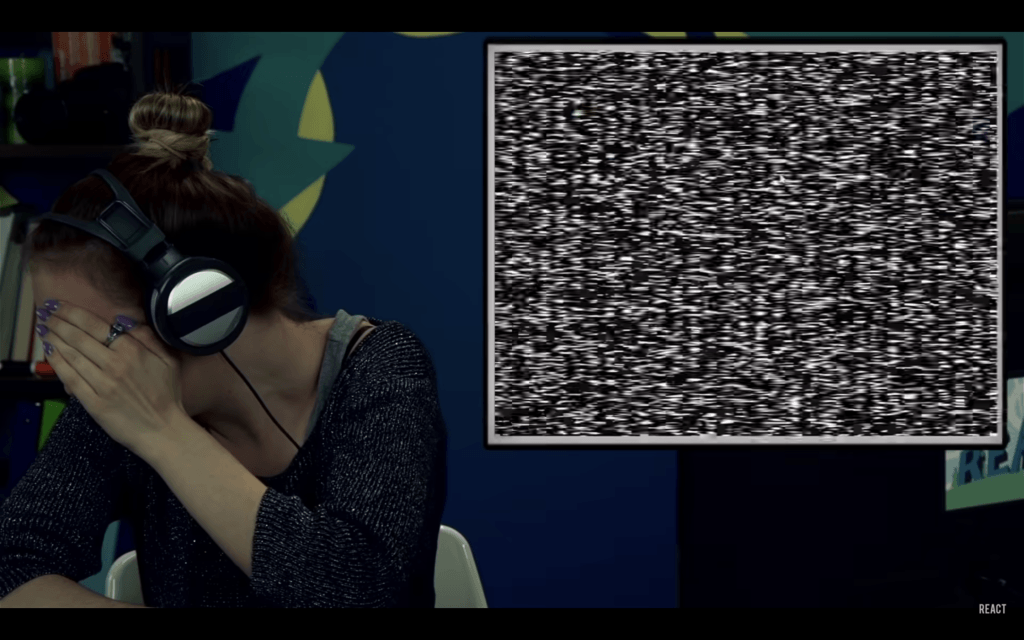

By 2010, a different style of reaction video was on the rise. The resolution increased; the cameras held still. A new formula solidified: on the left side of the screen, an interchangeable cast of subjects, often children or elderly people, stare at a computer monitor, striking poses of alternating confusion, amusement, and disgust. (It seems significant that the creators of these videos — who notably acted as producers and talent scouts rather than stars — were drawn to the subjects who felt the least at home online, subjects through whom we could rediscover the alien wonder of a digital world already calcifying into a set of stock tropes and gestures.) On the right side of the screen, in an inset, another video plays. We watch this original video and the subjects’ reactions side by side in an impossible space. The overall impression is less of an improvised performance than of an amateur psychological experiment: The subject is exposed to a stimulus, the subject reacts, and a brisk interview follows.

What were the results of these experiments? Commentators at the time had grand theories. “Part of the appeal of reaction videos,” the New York Times Magazine declared in 2011, is that “they allow us to experience, at a time of increasing cultural difference, the comforting universality of human nature.” Another article, published five years later, invokes mirror neurons. Benny and Rafi Fine, whose REACT YouTube channel popularized the now inescapable split-screen format, have spoken of the reaction video as a sort of “time capsule,” a dispatch to researchers “a hundred years in the future” on how we lived today. A more cynical read would be that what the pioneers of the reaction video really discovered was not a monument to human nature or a technology for archiving sentiments, but a kind of lab-grade, industrial-strength, self-propagating supercontent. Osama Bin Laden’s death, “Jack and Diane” by John Cougar Mellencamp, Shark Tank business schemes, various obsolete technologies, the lectures of Jordan B. Peterson, cooking tutorials, seemingly every video game ever made, and of course, other reaction videos: The reaction video proved to be an omnivorous genre, capable of metabolizing all these and extracting more content from them. Channels devoted entirely to reacting appeared, while existing YouTube personalities scrambled to move into the reacting space. Perhaps the best-known “rule of the internet,” first codified by 4chan users around 2006, is that “if it exists, there is porn of it.” If they had drawn it up just a few years later, the anonymous lawgivers might have added a corollary — if it exists, there is a reaction video to it.

Still, the reaction video had its finger on the pulse of something deeper than even the most breathless commentators realized back in the early 2010s. Consider the outrage the Fine brothers met in 2016 when they filed for a trademark on the reaction video format itself. The claim was all but nonsensical — and not just because the reaction video had entered the internet commons, another genre like the sonnet or the fugue, but because by that time, the reaction had simply become a fundamental unit of online life. That same year, Facebook supplemented its “like” button with the now-familiar repertoire of “reactions”: icons for “love,” “haha,” “wow,” “sad,” and “angry.” (“Your news feed is about to get a lot more expressive,” an announcement in Wired threatened.) Three years earlier, Giphy had developed a tool for embedding images from its gif library in social media posts, the precursor to today’s “gif keyboard.” These features formalized and centralized elements of earlier internet reaction cultures. Long after the stock vocabularies of “my face when” and “that feel when” were consigned to the dustbin of cringe, their logic lives on in the reaction icon, the reaction image. In a real sense, the internet itself was becoming, to invoke the name of the Fine brothers’ ill-fated video-format-licensing venture, a “React World.”

Spend enough time in its swirl, and you may eventually start to suspect that today, all content is reaction content

The first operation the reaction video carried out, then, was to isolate and give an aesthetic form to the unit of the reaction, the pulsating subatomic particle whose mad spin and swerve have come to fuel the platform-era internet. After all, the reaction, whether in the form of a like, a swipe, or a video, is the point of contact between content and the human body. It is the friction of this contact, as the average user surely knows on some level by now, that generates data — and hence, revenue. In its scenes of ecstatic tears and helpless retching, the reaction video showed us what poet Charles Bernstein called, in a very different context, “content’s dream”: simply, and without regard for context, to elicit engagement. And through that engagement, more content. Mark Greif once argued that “the reality of reality television is that it is the one place that, first, shows our fellow citizens to us and, then, shows that they have been changed by television.” Does the reaction video not do something similar, showing us that content can shock us, delight us, move us in some minimal but lasting way?

Once the reaction was isolated, it could easily be detached from the object or event that prompted it. It is easy enough to see that the serpents’ grip is the cause of Laocoön’s agony, while Edvard Munch’s The Scream feels like a closed system, the abyssal meaninglessness of the world the figure confronts registering indirectly in the distortions of form and color. But the essential elements of a video like “Double Rainbow,” as Sianne Ngai has pointed out, can easily be swapped out and connected up with different objects. Ngai reports as a case in point one “especially funny mash-up overlaying the soundtrack of [reactor] Vasquez’s moans and cries with shots of the minimalist sculpture of Donald Judd.” So too with other reaction media like the reaction gif: a Big Brother contestant’s spit take becomes a response to a Twitter clapback; a child’s uncertain grimace becomes an all-purpose indicator of discomfort. The reaction itself ceases to have anything to do with its prompting event and becomes part of a shared vocabulary available for use in any situation. The universalism of the reaction video’s early boosters returns in zombie form, not as the triumph of a common human nature but as the institution of a standard format for experiences.

And yet there is something quaint about all this in our present moment, in the uneasy early dusk of Web 2.0. If this is so, maybe it is because today the reaction hasn’t simply detached from its initial stimulus, but dissipated into the ether of the web, becoming the very air we breathe. It is one thing to repurpose a segment of television into a reaction gif. It is something altogether different to watch, on the same screen, live footage of a character’s progress through a video game level, the face of the Twitch streamer controlling the character, and the barrage of emotes in the stream’s chat — or else a TikTok duet, where one poster’s reaction melds seamlessly into the original video, or the cascade of reaction icons that tumble across a Facebook Live feed. The overall effect is one of strained, laggy simultaneity. Action and reaction lurch toward one another until they seem to take place at the same moment. Maybe one day streaming video will be accompanied by before-the-fact reactions — something like the prediction algorithms used by gaming and videoconferencing platforms to synchronize inputs from their far-flung users.

The reaction video proved to be an omnivorous genre, capable of metabolizing and extracting more content from content

A decade ago, Ngai wrote that “what we might call Other People’s Aesthetic Pleasures have become folded into the heart of the artwork, essentially providing it with its substantive core.” On today’s internet, we might say that Other People’s Engagement has lost its status as a penumbral or secondary element of a given piece of content and become aerosolized, ambient, the stuff of atmosphere. And as with our material atmosphere, things are overheating. The feeling of an internet that barrages us with reactions, and that solicits our own reactions with increasing desperation, is the feeling of living in an anxious attention economy. How passionately and vocally loved or reviled must content be to earn our attention? Is there even any attention left to extract, or have our reserves been exhausted? And how loudly must we scream, how much of ourselves must we put into our displays of shaking, crying, throwing up, to be heard through the din? Maybe the atmosphere of Other People’s Engagement insulates us from the exertion of having to react to every little thing ourselves. But maybe it is simply polluted air.

I sometimes wonder what a nonexpressive internet would look and feel like. Not an internet free of displays of emotion, but one where such displays are not compulsory, inescapable, baked into every piece of content and diffused through ambient space. Would this require a return to a “read-only” sensibility — ejecting the everyday user from the creator’s stage and throwing them back into the audience? Surely not, though the idea is not without its nostalgic pull. Maybe more simply, it would be an internet more hospitable to lurkers; to non-reactors, or at least to those who prefer to react in person only, to keep their reactions to themselves rather than offer them up as tribute to keep some hypermonetized media phenomenon burning with shrill and artificial insistence. It would be an internet where our reactions belong to us again.