Dead people speak on screens every day. This fact blurs, in a sense, the distinction between who is dead and who is alive. The dead never rest and never go away; their images are always available to the living. We can use the dead to pursue transcendence — a heightened state of stimulation where the bodies of both the viewer and viewed recede. By viewing death in a state of infinite proximity that maintains infinite distance, the viewer can “other” it, categorize it as not their own even as they access its state of sublime oblivion. This is what death is, post-screens.

When the violent, painful deaths of historically marginalized people are featured in public as though everyone has a right to watch, their visibility seems to confirm the othering distance, as if they deserved oppression and suffering. The deaths delivered to us in digital spaces are marked by centuries of earlier societal biases and sanctioned killing — in ancient Rome, the killing of slaves (different social status and ethnic background) and Christians (religious difference); in Renaissance England, those violating the English Buggery Act of 1533 (different sexual orientation); in the United States, the Wilmington Massacre of 1898, the Tulsa Massacre of 1921, the Rosewood Massacre of 1923 (racial difference), to name a few. But the pain and death we see onscreen is not ultimately reserved only for the socially vulnerable. Eventually it will happen to everyone.

In 1978, Marshall McLuhan wrote in New York magazine that “death on TV is a form of fantasy.”

On television, violence is virtually the sole cause of death; it is only on soap operas, and then very rarely, that anyone dies of age or disease. But violence performs its death-dealing service quickly, and then the victim is whisked off camera. The connection of death to real people and real feelings is anonymous, clinical, and forgotten in the time it takes to spray on a new and longer-lasting deodorant. The fantasy violence on TV is a reminder that the violence of the real world is much motivated by people questing for lost identity.

Today, “television” is no longer tied to the television set or a dedicated TV industry. Onscreen pain and death still sustain viewers’ fantasies about violence, but with screens omnipresent, it is even easier for people to take in images of othered death to distract themselves from their own detachment. Consuming the pain of others as pleasure or entertainment brings on a sensory overload that allows us to forget our own pain, and this overload is now available on demand.

Because pain and death feed curiosity, they are reproduced across the internet for clicks. Contemporary calls for violence are tinged with the possibility they might appear onscreen. People look at and watch snippets of pain and murder, a seemingly endless supply of people at their moment of death, because they can. They watch because these snippets are part of the news or an imagined future history. They watch because they should “bear witness.” They watch because the snippets are there and there is nothing better to do. They watch for the sensual experience and then deny it.

Consuming the pain of others as pleasure or entertainment brings on a sensory overload that allows us to forget our own pain

Videodrome, David Cronenberg’s 1983 McLuhan-influenced sci-fi horror film, explores the consequences of the increasing intensity of screen stimuli. The film puts McLuhan’s theories into practice through Max, its protagonist, whose immersion in onscreen violence prefigures fears about screen obsession today. According to Professor O’Blivion, the movie’s McLuhan doppelgänger, the viewer’s innermost desires appear onscreen as high-definition visual stimuli: “The television screen has become the retina of the mind’s eye,” he declares. Can the same now be said of our phone screens?

The film takes as its starting point the technologically mediated alienation of self and detachment from reality that McLuhan called “amputation.” Amputation occurs when media extend parts of the human body to the point where they no longer matter or cannot be sensed. “In the physical stress of superstimulation of various kinds, the central nervous system acts to protect itself by a strategy of amputation or isolation of the offending organ, sense, or function,” McLuhan writes in Understanding Media.

While this amputation can seem like a spiritual transcendence, this is an illusion. In moments of technologically mediated rapture or pleasure — losing a day to binge watching a show, looking at foodporn, naturporn, spaceporn, pornporn, stuck in an endless refresh cycle on your favorite social network and websites — one is amputated, in McLuhan’s sense, from the body: “Such amplification is bearable by the nervous system only through numbness or blocking of perception,” he argues. The body stops existing as the medium of experience, and one gets lost in sensuality itself. The internet, too, offers this sort of sensuality with diminished bodily attachment — a sensuality processed mainly through the eyes. Digitization has allowed for the binge watching of everything, with increasing levels of intensity matched by increasing levels of self-amputation. The digital self becomes the whole self.

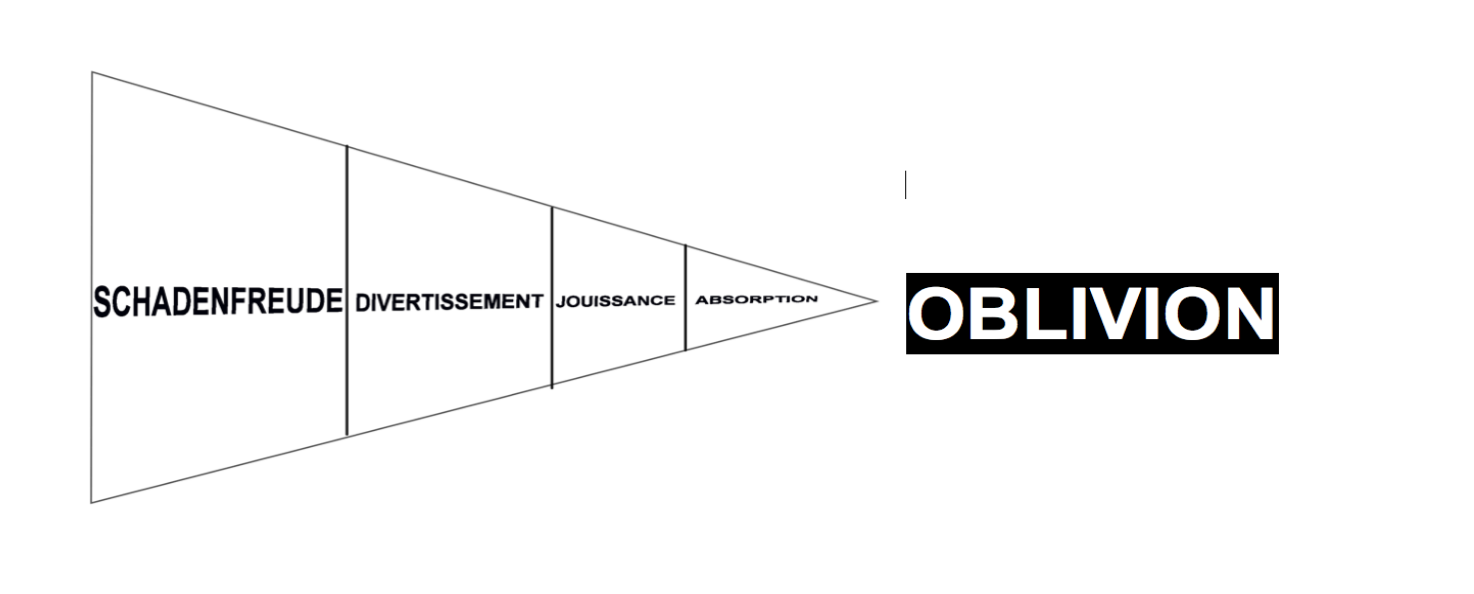

What is it like to be online, to exist on the screen, to be among the dead, to lose oneself in a transcendence that is indistinguishable from oblivion? Through Max’s experience in Videodrome, we can trace a four-part process that leads from a compulsive curiosity about the suffering and misfortune of others to a psychic space that mimics the death in the images themselves. As Max becomes absorbed by Videodrome, a broadcast that airs intense torture films on “secret airwaves,” the sex, pain, and death — of others and of the self — that it depicts become a constant hallucination that structures Max’s experience as simultaneous extension and amputation. In its insidious intensity, Videodrome prefigures the digital social media machine we now live with, where elements of the dark web seep into the mainstream indexed web.

When Harlan, Max’s assistant, first discovers Videodrome, he shows Max a 53-second video of a woman being tortured with a whip by two men in black. It’s reminiscent of the viral videos of teens fighting or being gang raped that circulate on social media. As Max watches it for the first time, we can see him being pulled into the screen, speaking little and shielding others from seeing it with a sheet of paper. His second viewing is different. His eyes are still riveted to the screen, but he can discuss it with Harlan without shielding the view. “You can’t take your eyes off it,” he tells him. “It’s so realistic.”

The implication is that Max is grooming himself to watch more by becoming more detached, and that desensitization does nothing to reduce the compulsion to watch. If anything, knowing that one can take in more content intensifies the compulsion. This moment epitomizes the first step toward oblivion: schadenfreude. This schadenfreude is addictive, because the afflictions of others can be affirming for ourselves. As psychologists Jaap W. Ouwerkerk and Yoka M. Wesseling argue in this report, “misfortunes happening to others provide an opportunity to protect or to enhance one’s self-view.” Schadenfreude pleases us because it makes us envy others less, as their paper argues. The rush of momentary contentedness soothes envy, a sort of loss of identity, without changing the situation. We need more to be okay. And we consume it without guilt, thinking, At least it wasn’t me.

If disturbing content no longer shocks, one can still get a charge out of fine-tuning one’s apathy

Schadenfreude can and does go viral. But after consuming enough suffering in this mode, viewers may find that schadenfreude no longer affirms or soothes. If “we live in overstimulated times,” as Nicki Brand, a talk-radio psychiatrist in Videodrome, puts it, then it is no surprise that Max would be driven to seek more intense viewing experiences. After all, in the media world he has created for himself, where he re-broadcasts “everything from soft-core pornography to hard-core violence,” more extreme content can be hard to uncover.

Seeking higher intensity stimuli triggers the next step on the path to oblivion: the conversion of extremity to divertissement. If disturbing content no longer shocks, one can still get a charge out of fine-tuning one’s apathy. Then the pleasure in consuming intense content is no longer dependent on imagining the other people suffering. Instead, images of pain and death become enjoyable in and of themselves, simply because they are a diversion from the everyday.

In Videodrome, Max’s world is defined by divertissements. It is his business — he curates material for television channels. “I care enough to give my viewers a harmless outlet for their fantasies and their frustrations,” he explains in justifying his programming. “As far as I am concerned, that’s a socially positive act.” This makes him like someone who redistributes violent content in social media today. At this stage, the pleasure from extreme content, the possibility it affords for transcendence, stems not from being shocked by it but from being able to share it. It is no longer enough to merely consume it.

Eventually the pursuit of distraction ceases to be an escape from something else or a way to affect other people and becomes a positive goal in its own right. As numbness takes hold, the need and search for something that can reawaken a throb of ecstasy and release into a calm nothingness rules. This is next step to oblivion: jouissance, an intense, ecstatic release that consolidates the detachment and heterogeneity of divertissements, bringing consummation to the constant consumption of disparate experiences.

Videodrome juxtaposes death with sexual arousal to evoke this next stage. When Max receives a Videodrome tape depicting Professor O’Blivion’s strangulation (suggesting O’Blivion has been dead all along yet alive onscreen), his executioner reveals herself as Nicki Brand, who begins to come on to Max through the TV. Her mouth fills the screen, and in a surreal sequence Max plunges his head directly through it. Nicki transitions from executioner to object of desire seamlessly.

Such a transition is not altogether different from viewers flipping through tabs or compiling various information flows through social streams: We experience such juxtapositions, and such conflations of divergent emotions and desires routinely. The image, the vicarious experience that will arrest us, that will shift us from divertissement to jouissance, depends on momentary moods and transient desires — the release that jouissance anticipates resists uniform reproduction. But the raw materials to bring jouissance into being are just a click away.

The pleasure from extreme content stems not from being shocked by it but from being able to share it. It is no longer enough to merely consume it

In Videodrome’s final scene, Max is reunited with Nicki, who is there to guide him toward freedom. She promises that it is possible to become “the new flesh” — the complete amputation of the body through Videodrome technology. “Don’t be afraid to let your body die,” she tells him and then disappears. His hand that had been slowly turning into a flesh gun throughout the second half of the film has completely transformed. He raises his hand/gun to his head and pulls the trigger. The film cuts to a television and guts spill from the screen. Then it cuts to a view of the room, and a fire burning in the middle of it. Max kneels in front of the fire and looks directly at the camera, the future audience. His hand/gun comes up to his head: “Long live the new flesh.” He closes his eyes and slightly smiles. There is the sound of a gunshot, and the screen goes black.

Max’s screen death remains unseen. The audience is left with an impression of it but not the actual footage. In its place are mediated memories of Max’s living body as it moved and occupied scenes throughout the film. He is the new flesh. The images onscreen are not just his analogue; they are him. He is with Nicki and Professor O’Blivion, a being experienced through the images and clips captured during his time as the old flesh. This is the final step toward oblivion: Absorption. I am a part of this thing. In my consuming it, it has consumed me. It is new life. Absorption is the point where autoplay is not just engaged; it is vital.

Videodrome forces viewers to partake in the search for pleasure through the screen just as Max does. I think this is why when I’ve asked people I’ve watched it with if they enjoyed it, they always say they are unsure.

I get a similar response when I ask people about social media.

What I find most confusing, or comforting, about the internet today is that we assume that it consists only of what becomes popular and ends up on all our screens, be it kittens or death. Perhaps we want to continue to deny that humans have always done horrible, unspeakable things to each other while still liking kittens. Because we weren’t able to see and share it, we could deny its normality. Today, these things aren’t happening in their own isolated physical worlds. The internet lets people connect across horror for shock value, pleasure, or diversion.

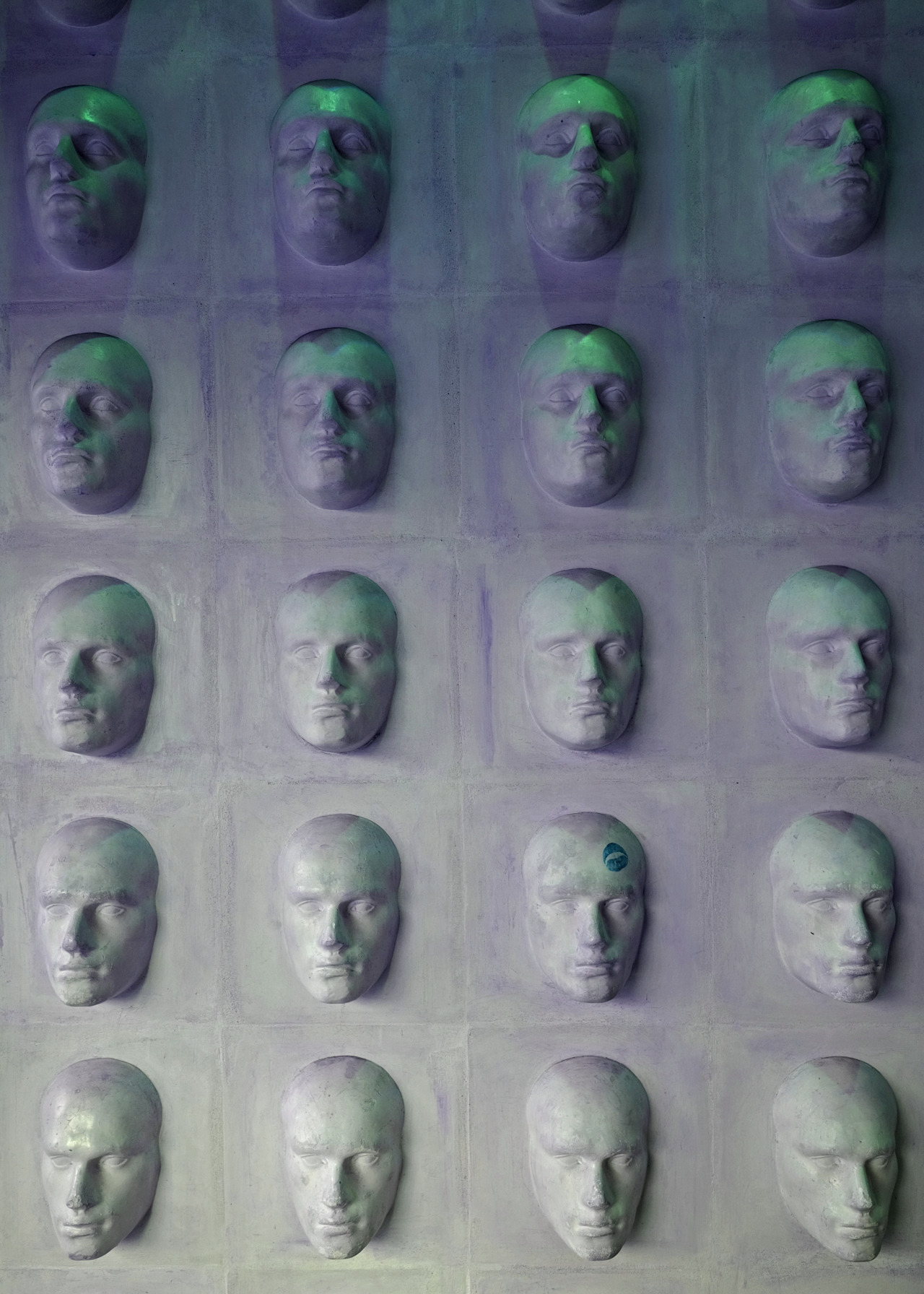

Onscreen, we watch the same things on repeat until they lose their specificity. When the clinical-ness of death that McLuhan hinted at is realized on modern screens, viewers don’t see themselves reflected; instead the dead become nameless objects. In the beginning they are named. Slowly they move to being defined statistically by their characteristics. Finally they become part of a series of hashtags defining the same problem over and over, stuck in a loop of content.

I don’t believe humans are necessarily sadistic by nature. However, we do seem to be naturally curious and sensual. Images of torture and pain can give us a sense of control in hopeless situations. Viewing pain and death online allows viewers to ignore the fact that their own pain amounts to an emptiness and a loss of identity. This visibility narrows rather than expands the human panorama. Even as society becomes saturated with screens and the apparent accessibility of others’ lives, we remain oblivious to how the people on the other side of the screen are just humans too, searching for their own identity, belonging, and divertissement. Ignoring that won’t keep us from crossing over to that side ourselves.