As you might deduce from some of the place names in Nevada — “The Loneliest Highway in America,” “Fire Valley,” “Jackass Flats”— the state isn’t exactly welcoming. If anything, the state prefers ghosts and guns to people. The town of Tonopah hosts not one, but two, haunted hotels: the infamous Clown Motel, and the upscale Mizpah Hotel, where visitors come hoping to hear the disembodied voice of a woman who was reportedly brutally beaten and killed by a jealous lover in one of the rooms. Goldfield, the next nearest town, boasts the abandoned Goldfield Hotel, the subject of multiple ghost adventure TV show invasions; its last living occupants were the military families working at the nearby Tonopah Missile Range.

Of the 2,041 nuclear detonations that occurred worldwide in the 20th century, over 1,021 took place in Nevada

These small towns with folklore allure live among the state’s lesser known historical locales: experimental military test sites. Nevada’s isolation has long made it welcoming to a large military presence; because its high-desert climate is similar to that of the Middle East, it is also seen as a prime spot to test drones and stealth aircrafts. Many of the drone pilots navigating the airspace above the Middle East are stationed just outside of Las Vegas, in suburbia. Besides the Tonopah Missile Range, the most famous sites include the Nevada Test Range, the Top Gun training program, the Hawthorne Army Depot, and, of course, Area 51, a U.S. Air Force facility better known for its connections to alien conspiracy theories than the development of deathly stealth aircrafts. If you talk to the locals in the areas surrounding Tonopah, Alamo, and Rachel, you’ll more often than not hear of a friend of a friend working on the base. If you’re lucky, they’ll divulge a UFO story.

Beginning in the 1950s, Nevada also became a frequent site for nuclear detonations: Of the 2,041 that occurred worldwide in the 20th century, over 1,021 took place in the state. Excluding the tests done at sea, 41 percent of all nuclear detonations were concentrated here, on 0.0019 percent of the world’s land. Until the 1960s, most of these tests were atmospheric — above ground — which led to massive airborne fallout. The scientists relied on meteorologists’ predictions of the wind patterns, which often proved wrong. Most of the nuclear radiation took flight northward, seeped into the groundwater, and poisoned generations of local inhabitants, known as the Nevada Test Range Downwinders. Lawsuits against the federal government are still pending.

Like the lore of abandoned ghost towns and haunted residences, the nuclear fallout in Nevada has become an integral part of its identity and America’s identity. Amid the legends of murdered women and abusive cowboys, there is a legacy of nuclear radiation that will outlive even the best of the Western lore. At least a ghost story has an end.

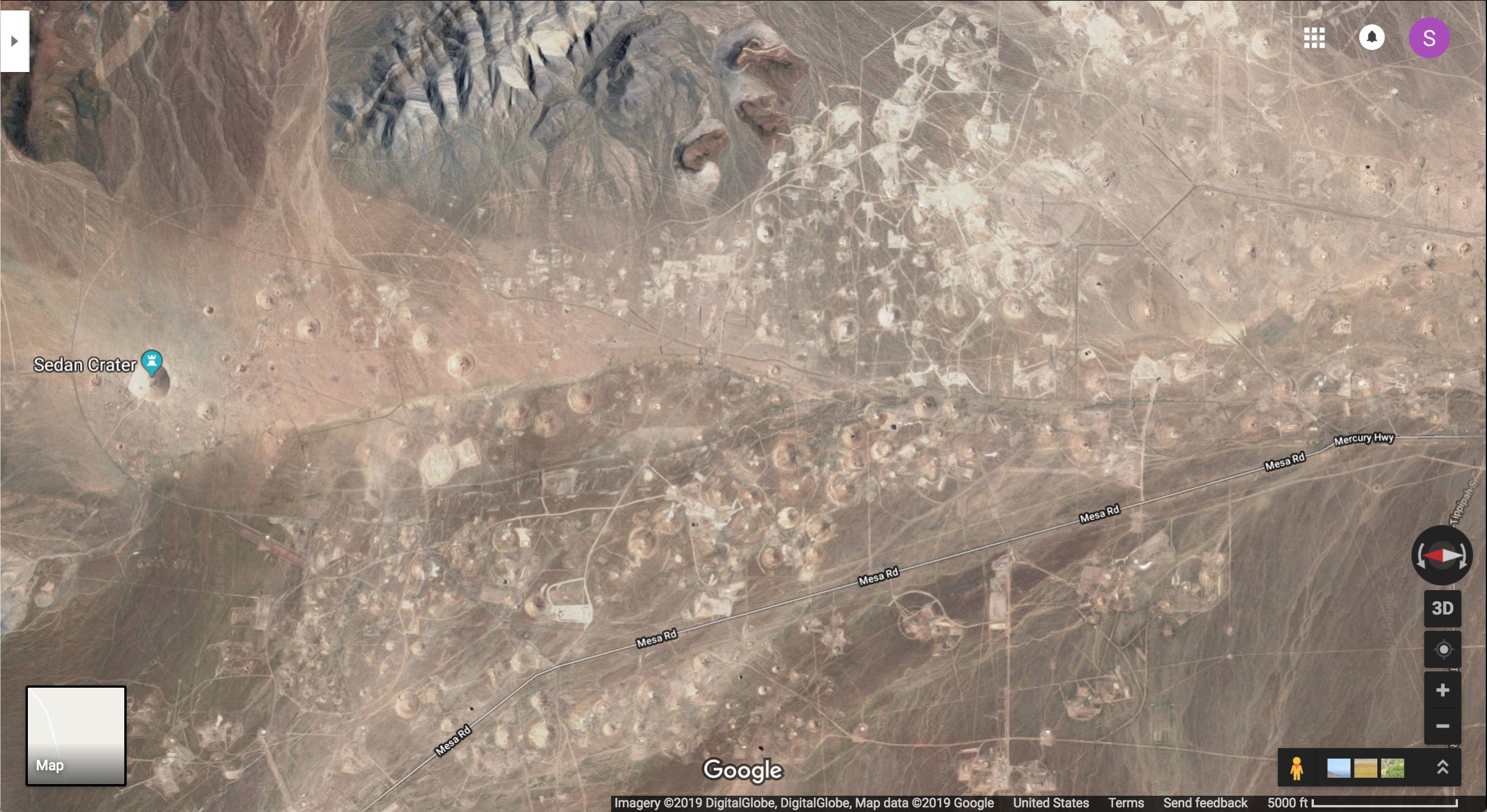

The state’s numerous test sites, and the pocks of devastation they have left behind, can be glimpsed in Google’s satellite images, but none of it is visible at ground level in Street View — the company hasn’t traversed the roads that access them with their camera cars.

Most cars making a journey across the state are freight trucks or local residents on their way to a slightly larger grocery store. But a small subset of vehicles belong to off-kilter tourists lured beyond the neon strips of Las Vegas and Reno by the promise of an authentic “Wild West.” Travel Nevada’s tagline, “Don’t Fence Me In,” speaks to the appeal of adventurous desolation. Tourists passing through the state revel in the lack of human presence, but at the edges of Nevada’s test sites, one finds remnants of a different kind of human intervention.

The earth seemed soiled, toxic — a threat waiting to seep through the rubber soles of my hiking boots. If I walked, I felt like I would become part of the landscape

The Nevada National Security Site hosts a popular bus tour of its main testing range outside of Las Vegas, one of the largest nuclear test ranges in the world. Visitors must book years in advance. The bus, which leaves Las Vegas at 7:30am one Saturday a month and returns at 4pm, offers visitors the opportunity to see the major craters, the bent metal I-beams, and the low-level radioactive waste management sites up close. By satellite, they take on the communicative appearance of hieroglyphics, or scars.

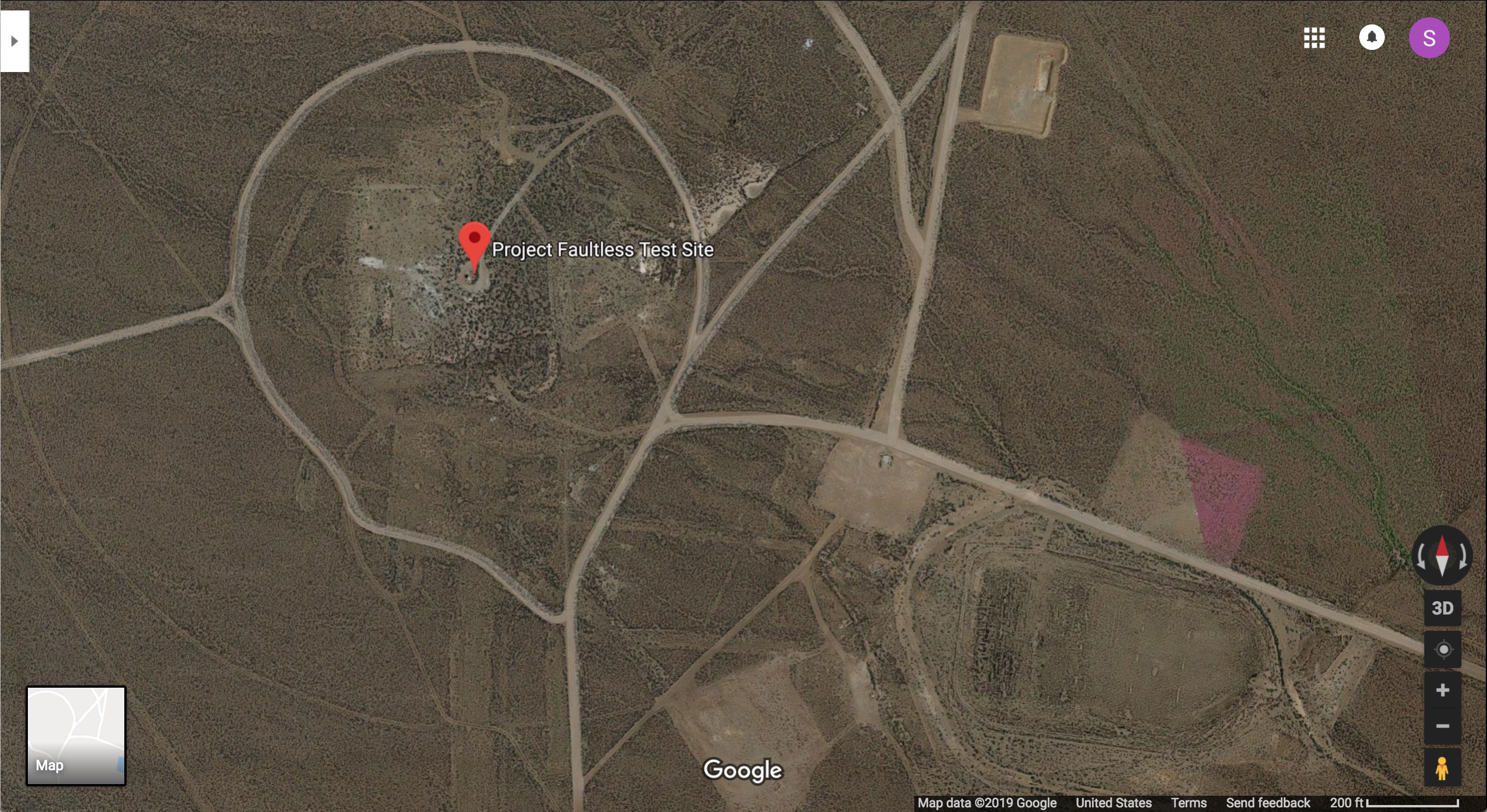

As an alternative to a bus tour, you can drive across little-known dirt roads to the location of the Project Faultless test, where a one-megaton nuclear bomb was detonated 3,200 feet underground on January 19, 1968 at 10:15am. The site is a little over 90 miles from Tonopah, or 250 miles from Las Vegas.

U.S. 50 may be nicknamed “The Loneliest Highway in America,” but it is still a major artery for crossing Nevada. U.S. 6, which heads east out of Tonopah toward the site of Project Faultless, feels existentially lonely in comparison. It’s not just the lack of traffic, but the pure isolation. Driving the 66.9 miles between the Duckwater junction and Warm Springs, you’ll find one or two ranches close to the mountains, a small oil rig outpost, and an even smaller abandoned grade school that no longer operates. Spend ten minutes scrolling on Street View, and you won’t see a soul etched into the pixilated archive. Like traveling to the edge of a video game’s landscape, there’s a constant anticipation that maybe the full scene just hasn’t loaded yet.

Continuing on U.S. 6 east, after crossing a set of mountains, you’ll reach a well-maintained dirt road, where the Google car abandons us — the only images available have been uploaded by Google users, in an attempt to memorialize a space that seems to want desperately to be forgotten.

After 12 miles on this dirt road, the earth suddenly sinks approximately 16 meters lower. The land looks wrinkled, and fissures in the desert floor span into the distance. The road splits into seemingly random paths, though satellite images show a circle enclosing the Project Faultless test site. On one side, a plaque commemorates the project. On the other, white spray painted outlines of human figures raise their hands towards the sky. The fault lines that resulted from Project Faultless proved to scientists that the area was too volatile for underground nuclear testing, but such testing would continue at other locations in southern Nevada until the 1990s.

The first time I came here, though I had already spent a month driving solo through the state, exploring the desert, I didn’t get out of my car. I had come to bear witness to something, but I preferred the view framed by my windshield. The earth seemed soiled, toxic — a threat waiting to seep through the rubber soles of my hiking boots. If I walked, I felt like I would become part of the landscape. The fact that cattle now graze on the land and drink the water didn’t quell my anxiety. A married couple I’d met in Eureka, north of the site, who had given me driving directions and corrected the map in my atlas with pen, recommended I wash my car after visiting.

When I visited the site again two years later, I fought against my paranoia and chose to get out of the car. I had come with my father, and the pure silence felt less daunting with someone to talk to, the weight of implied culpability easier to split. We didn’t see a single sign of life, until I noticed a small observatory on the peak of a nearby mountain. I imagined their view of the sky at night with the absolute absence of light-pollution. We took some pictures and left.

On a two-dimensional screen, the test site shrinks into a distant object, a few cryptic snapshots. There’s a cruel nihilism to their accessibility. The incomprehensibility of the landscape, its vastness, and the myths that hang in the ether like a storm cloud, become an incomprehensibility of images. How does one make sense of atoms breaking, drones striking, the earth tearing, from satellite photos? The long, desolate trip out to Project Faultless might seem morbid, a form of disaster tourism starker than a night at a ghost motel. Or else it might seem like a waste of a long day. The purpose was simple: an attempt to distill the scale of this unimaginable devastation, past and future, to an impression.