GUIDED TOURS is a look at a historical or cultural site undertaken on Street View, led by a knowledgeable escort. Tours can last the length of one long exposure or block; others can take in multiple sites and last for decades. If you’d like to nominate a place, please walk us through it.

In 1898, the Village for Epileptics at Skillman opened in central New Jersey, the third such institution in the U.S. When I was a teenager, I took a quick drive with some friends through the remnants of it. None of us knew anything about it at the time; it was just a mysterious, spooky ruin of old, boarded-up buildings surrounded by tall grass, seen off in the distance from the road. As we passed through, we feigned fear over its creepy vibe. I think I just saw a man standing in the grass!

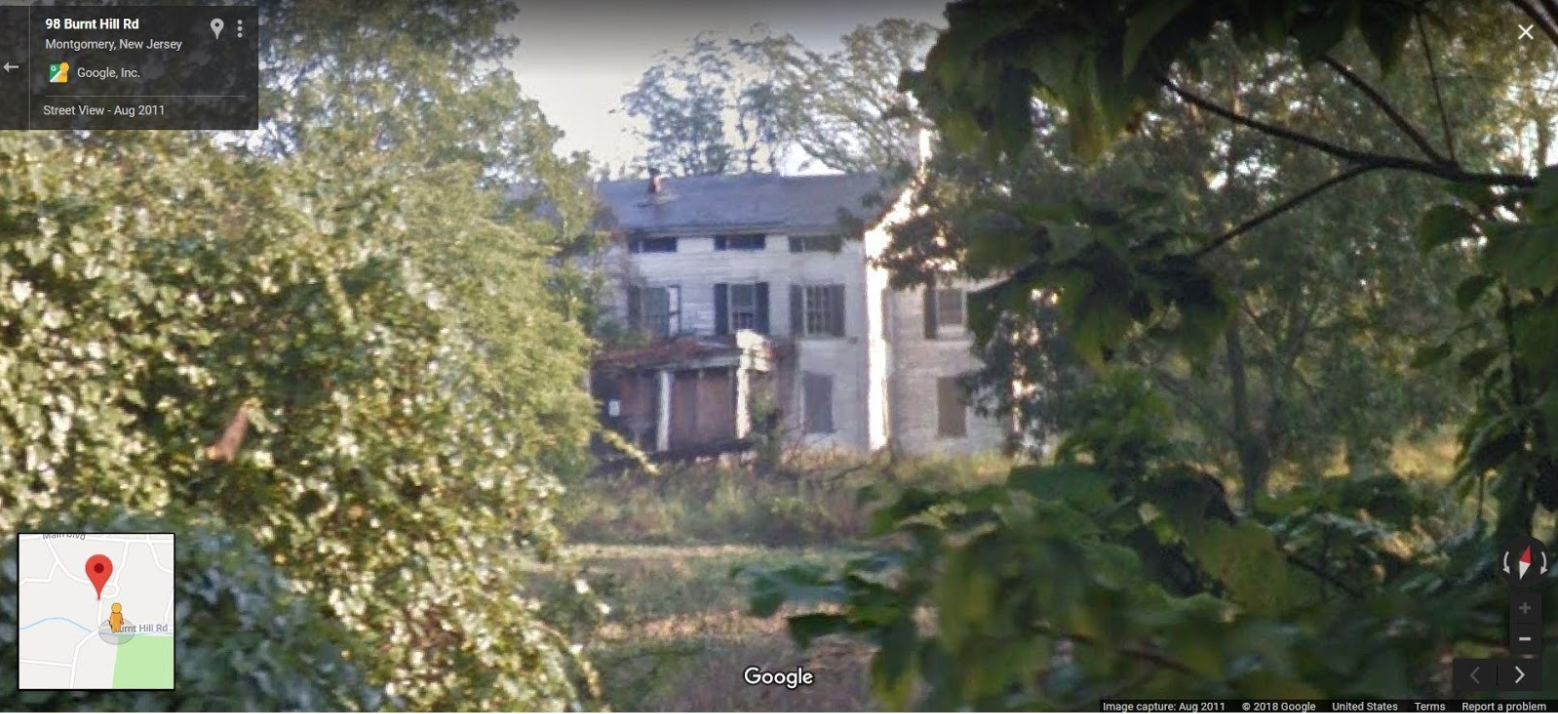

Most of the village was demolished in 2007, when Street View launched, but one can still see traces in a capture from 2011. The Maplewood Farmhouse, which hosted the institution’s first seven patients before the surrounding village proper was built, is still partly visible beyond a wall of trees. It eventually became the superintendent’s residence. On Street View, it can be seen only via a handful of nodes along Burnt Hill Road, materializing in and out of view like a specter as you click through the area on the map.

Today, the house is gone, having burned down the same year the capture was taken. On Street View, though, the boarded-up house retains a tantalizing inaccessibility. The unpaved, trodden path leading up through the trees toward the home taunts us with the possibility of a way in, but it can’t be zoomed in on or clicked through. This apparent arrival at a place since lost to time turns out to be another ghost.

Toward the end of the 19th century, medical science viewed epileptics as straddling the line between sanity and insanity. The etiology of the disease was not understood, and seizures were seen as uncontrollable and dangerous periods of insanity that could launch an epileptic into a murderous rage, no matter the nature of their ordinary behavior. The perceived danger of these fits led to the forced institutionalization of epileptics, but asylums across the U.S. were already crowded. In 1902, it was estimated that more than 2,500 epileptics were in the state of New Jersey alone. One idea, held to be progressive at the time, was to take epileptics out of “lunatic asylums” and place them in their own institutions — not because they were seen as requiring less supervision so much as their seizures distressed other patients.

Largely forgotten now, these institutions for epileptics were designed to be self-sufficient, village-like communes in which patients could experience a sense of usefulness through work and socialization — as much normalcy as could be allowed for a community in quarantine. Writing in 1910, J.D. Munson, the resident pathologist at the second such U.S. colony, in Sonyea, New York, blueprinted “the ideal institution for the epileptic.” After noting that an epileptic’s seizures meant their presence “cannot be endured beyond a certain point by his family or associates,” he recommends that in such villages, “the buildings must be such as to withdraw the suggestion of institutionalism and there must be plentiful opportunity for work … there must be provision for education, amusement and religious instruction — in every respect a complete village.”

The veneer of a self-sufficient community hid a more troubling purpose that went beyond segregation. Sixteen years after the village was established, Charles O. Jones celebrated it in the Atlanta Constitution as a medical autocracy in which “the medical superintendent is necessarily a czar.” That superintendent was David Weeks, a prominent supporter of the era’s eugenics programs and an advocate for involuntary sterilization of the “feeble-minded,” criminals, epileptics, and more. In 1911, New Jersey Governor Woodrow Wilson signed “An act to authorize and provide for the sterilization of feeble-minded, epileptics, rapists, certain criminals, and other defectives” into law. Around this time, the Skillman village hosted the Eugenics Section of the American Genetic Association, a conference aimed at completely eradicating epilepsy, which they suspected of being exclusively hereditary, in the span of a few generations.

When drugs to treat epilepsy hit the market by the mid-20th century, the village was no longer required for its original purpose. It was transitioned into a treatment facility for addiction, cerebral palsy, and developmental disorders among other conditions. Eventually it was shut down in 1998 — a hundred years after it opened. Locals became impatient to see the village completely knocked down: The cottages upset children at the nearby elementary school; the asbestos in the pipes and chemicals in the soil also posed significant safety risks, as did the possibility of the buildings themselves collapsing.

Google’s 2011 capture of the village as a whole is incomplete, a map of false choices. Exploring the space, one comes across several forks in the road: unpaved paths engulfed by the open maw of woodlands or crossing into the unapproachable horizon. There’s a disconnect between the captured images and the mini-map in the lower-left corner of the screen, which portrays streets that weren’t yet there when these images were taken.

The site is captured between two transformative processes: at the end of the village’s demolition but before the land’s development into the park it is now. It sits as a disjointed place in time, in a suspended state between decay and redevelopment. Like the village itself, its online capture has become obsolete. It provides nothing of the site’s history and the ideas that it was built to sustain. It only haunts and elides.

Much has been said about the appeal of “ruin porn” and the allure of abandoned spaces as an escape from the everyday. In “Undercover Softness,” philosopher Reza Negarestani writes of the ambiguities and apparent contradictions of decay. For example, a rotting apple appears to shrivel and shrink but results in a growth of maggots, smells, and new colors. Likewise, architectural decay creates a weirdly ambiguous space: The complex order of a town’s design suddenly melts into wilderness grown from it and spilling out.

Negarestani describes putrefaction as a process of “exteriorizing” hidden truths and systems — like the internal processes that rise to the surface as a body decays: “The ultimate truth of decay is that it is a building process that builds a nested maze of interiorities whereby all interiorized horizons or formations are exteriorized in unimaginably twisted ways.” Exploring what’s left of the village on Street View, I think of this “exteriorizing” process, and what the abandoned buildings signify about New Jersey’s treatment of some of its most marginalized and vulnerable people.

In the image above, we see one of the final few cottages in the midst of its demolition. The south-facing half is destroyed, exposing the home’s interior walls and even a door leading to an unseen room, almost like a dollhouse. While I was initially attracted to the village for its eerie character, this house stripped bare feels so much more mundane today: just a place where people lived their relatively normal lives as well as they could, given the circumstances.

Curious about what life was like in the blank space that as a teenager I saw as nothing more than haunted-house set dressing, I visited the New Jersey State Archives and looked through the Village Quarterly, a series of newsletters issued by the village’s printing class. What first struck me was that there was a village printing class. Inside the Quarterly’s first volume were general-interest articles — a biography of Benjamin Franklin, an explanation of lunar eclipses, notes of encouragement for times of distress — as well as jokes, puzzles, and local news items from each cottage in the village. I imagined the residents’ eagerness to share knowledge with one another about all sorts of random topics.

The 1911 eugenics law was never enforced. A state Supreme Court struck it down before it could take effect, making the government’s flirtation with state-mandated sterilization easy to overlook a century later. With the village no longer standing, its relation to eugenics can seem to disappear into a blind spot, as though it could have only happened long ago in a place we can afford to forget.