GUIDED TOURS is a cursory look at a historical or cultural site undertaken on Street View, led by a knowledgeable escort. Tours can last the length of one long exposure or block; others can take in multiple sites and last decades. If you’d like to nominate a place, please walk us through it.

In between Sheridan Street and Stirling Road in Hollywood, Florida is a stretch of road with three names. On a map you might see NW 89th Avenue but I don’t remember anyone ever calling it that when I grew up there. For those that lived southeast of that stretch of road it was called Douglas, and if you were from the northwest it was Pine Island Road:

Generally if you were well off you lived further out west in the new gated communities full of managers and professionals whose company had relocated them to the low tax, high humidity environs of South Florida. East was where you found the people who can remember when the malls West of Douglas were Everglades and sleepy motels instead of skyscraper condominium towers looked out over the beaches.

You can’t find any trace of the Waldrep Dairy Farm, which used to occupy the 530-acre expanse around this stretch of road, on Street View — Google’s history doesn’t go back that far — but if the images went to 2003 instead of 2008, you’d see the last cow grazing in the Florida heat.

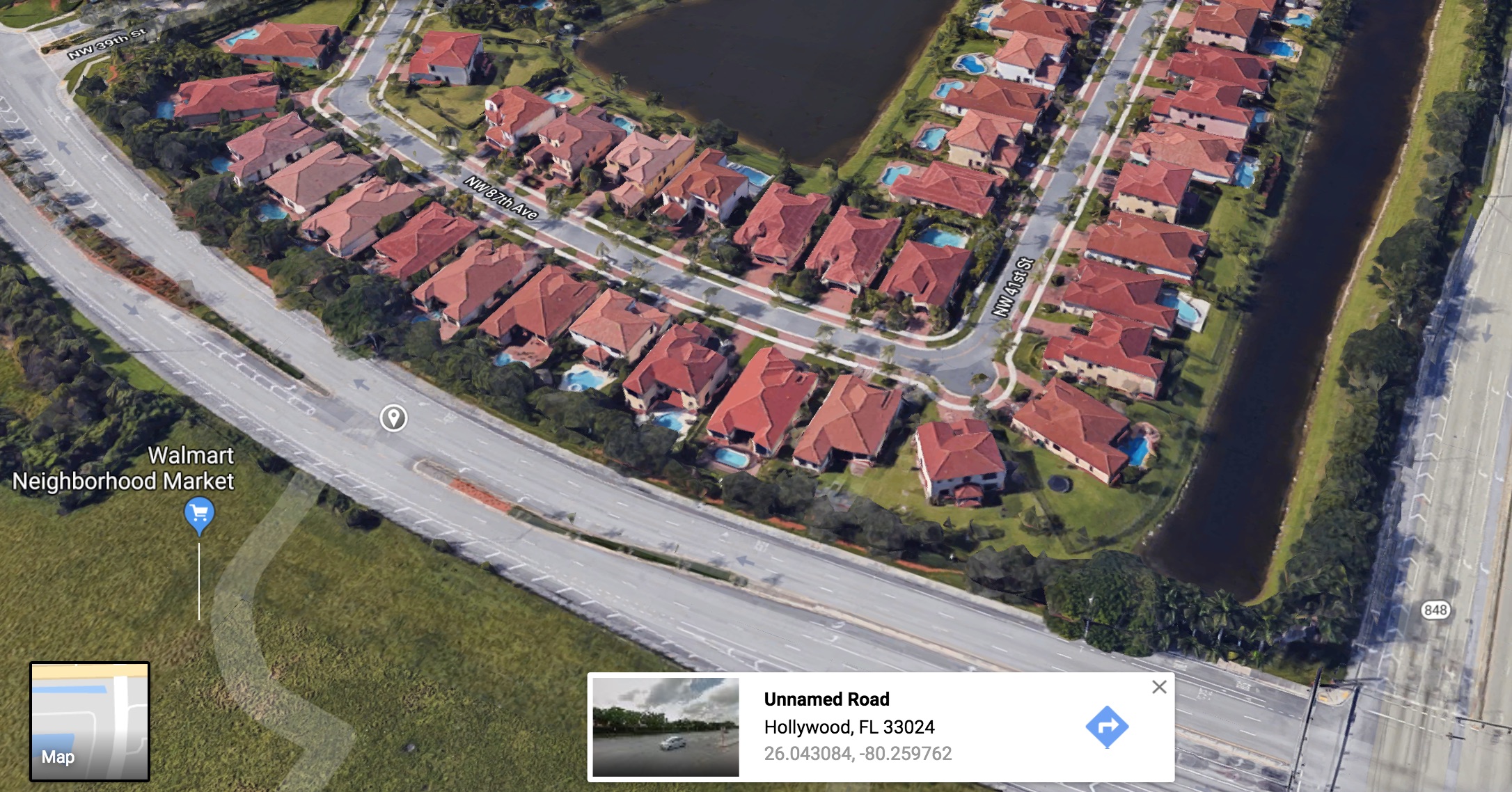

Wiley Waldrep died in 1997 at the age of 91, dreading the suburban sprawl encroaching on his farm. His kids kept it afloat for 11 years before selling the largest contiguous piece of undeveloped land in Broward County for $104 million to a development firm called TOUSA. TOUSA went bankrupt in 2013 and its subsidiary brands scattered to the wind. The former Waldrep Dairy Farm was snatched up by a new development company formed by two veteran developers who gave it the Spanish-sounding nonsense name “Monterra.” If you search online for the meaning of this word you’ll find that you’re not the first one to look: Message boards are full of people trying to figure out if it means “my land” in Spanish. Some will notice that montera is the name of the hat bullfighters wear. No one seems satisfied.

Building a subdevelopment is not unlike cultivating a farm. Before your bounty of ranch homes can rise from the Florida peat you have to till the land, irrigate it, and put up fences. In 2008, you can see the first thing to be built in a subdevelopment — the gate:

If you look closer at the Street View above, you can see the pillars that would have supported a metal gate and maybe a few lamp posts and a fire hydrant. A literal gateway to the uncanny, this failed crop languished for years. Fire hydrants, sidewalks, street lamps, and stop signs stood in an empty field forming home-shaped voids. Something eventually grew there, rendering the landscape completely unrecognizable to anyone who’d lived there just two years earlier. Even the languishing gate was torn down and a brand new one built in its place with a wider median and more turn lanes.

This was the inspiration for what I called my “postmodern birthday party.” Out in a field by my college, several hundred miles away from Douglas Road, I set out a blanket, surrounded it with tiki torches and filled a folding table with frozen snacks nuked to perfection including a centerpiece of Jimmy Dean breakfast sausage corn dogs wrapped in a blueberry pancake breading. I downloaded several hours of recorded numbers stations — mysterious voices assumed to be coded messages to far-away spies broadcast on shortwave radio — and they played eerily in the background. I was about as insufferable as the encroaching suburbs but so were my friends so it didn’t matter.

It makes sense that a generation that grew up in the booming Sun Belt suburbs would react strongly — either positively or negatively — to the postmodern condition. When you grow up in a geography of simulacra, where everything is just a half-remembered version of something from somewhere else, you either accept or reject the impurity of all things. You either demand a new kind of purity disguised as a return to a romanticized past or place, or you lean into kitsch, pastiche, and synthesis and all the combinatorial possibilities they offer. Monterra is either an empty gesture toward Latin influence or a neologism worthy of brand recognition.

South Florida’s suburban geography feels like it is straining against the postmodern only to fall deeply into it, like a gif of a cat falling into a bathtub ad infinitum. The term “o’clock” — a contraction for “of the clock” — was used in Henry VIII court as a means of distinguishing between announcements of time derived from sundials and those of counted units. To say it was 12 o’clock was to say that you consulted an artificial device rather than a pointer derived from natural shadows cast by the sun. Much of Florida feels like a clock, not disconnected from the universe but always referring to an index rather than something directly observable.

Suburban Florida rejects interpretation in favor of the clean lines of earnest branding. St. Petersburg was the first American city to ever hire a public relations manager, a fact that would not surprise anyone who has gone there or heard of the region’s notoriously large “scene-kid” population. It is a city surrounded on three sides by water — a fractal peninsula on a peninsula — and yet it is so thirsty.

At some level — I’m reticent to call it subconscious — Floridians know something is deeply wrong with where they live. There is a common refrain from people who leave Florida that just about everywhere else has more history, more fixedness. Out in the strip malls and cul-de-sacs that make up the majority of the post-war American South you get the sense that being told one was living at the end of history was psychically damaging. One can neither learn from history nor make it, and so you are both inconsequential and terribly free. Of course there is a history in Florida, one that is as violent, hopeful, and gut-wrenching as everywhere else. The maroon communities and Seminole resistance fighters that evaded and defended themselves against their governor Andrew Jackson and his trail of tears. There’s a dark joke in Florida urban planning that says home developments are named after what was killed in order to build the development. I had friends that lived in places named after birds, trees, and native people.

Floridian development coincided with the moment that, according to the geographer Edward Soja, “the despatialization of social theory seemed to be at its peak.” So while we were never at the end of history, there was a time, between about 1917 and 1960, that geography was on hiatus. Of course it is unlikely that the developers ordered the dredging of Everglades because Marcuse, Benjamin, Gramsci, and Adorno saw history as having radical potential and geography as merely (Soja again), “a dangerous fetter on the rise of a united world proletariat.” What is true though, is that the middle of the 20th century was the zenith of the American century and perhaps the last time that the North American continent seemed inexhaustible and the future inevitably better than the past. Vernacular architecture — building things such that they are simpatico with the environment and respectful of past traditions — denied the power of American industrial prowess. We were going to build bases on the moon; why would we build houses that needed less air conditioning?

It is this hubris that defined western, modern geographic thinking — both in the academy and in popular discourse — and skepticism of such sweeping generalizations is the postmodern condition. But whereas history is constantly being rewritten, geography stubbornly reminds you of what you once thought to be true. Each ranch house totally disconnected from public transport is a reminder of the easy motoring myth it was founded on. The half-built gates on Douglas Road are a contestation of limitless progress. Seeing that development eventually, slowly get filled out with homes adorned by barrel tile roofs and fat garages is an indication that we have learned nothing about the planet’s material limits. The architectural mishmash of false nostalgia and modern amenities is a decidedly postmodern American dream of regaining what you never had, achieving the promise of a lie.