GUIDED TOURS is a look at a historical or cultural site undertaken on Street View, led by a knowledgeable escort. Tours can last the length of one long exposure or block; others can take in multiple sites and last for decades. If you’d like to nominate a place, please walk us through it.

In the 1990s, when I lived in Tucson, I used to make the 400-mile drive to Las Vegas fairly regularly to visit my family. Up I-10 to I-17, then across the Carefree Highway to U.S. 93, a winding, once mostly two-lane road that went through the jagged cliffs and parched arroyos of an especially barren reach of the Sonoran Desert. I usually made this drive alone, and I would dread the segment from Wickenburg to Kingman. There were no guardrails for miles, as I remember it, and there was lots of time to daydream about going over the edge.

On this stretch of what was then mostly two-lane road, radio reception would fade to static and tractor-trailers would pile up at the passes and slow speeds to a crawl. Since then the populations of Phoenix and Las Vegas both nearly doubled, and the road has since been widened to four lanes to accommodate the increased commerce — a project that appears to have taken the better part of a decade and cost more than a quarter billion dollars — but you can still see here how the Street View camera car gets stuck behind an oil tanker for a while, until it breezes past it here.

Back when I had to drive U.S. 93, though, that pass would have been a white-knuckle maneuver: gas pedal floored, my four-cylinder Toyota Tercel lurching along in the opposing-traffic lane, me wondering whether something was on its way over the horizon to kill me. Whenever I had to make these daredevil passes, I would think about the white crosses that lined that road in the right-of-way, marking the traffic fatalities. According to this report, those crosses were once placed by the state highway patrol as grim warnings, a practice since discontinued. I clicked through Street View looking for examples, but I couldn’t find any, not at any of the curves or canyons or crossing where I thought I remembered them. They may have been removed during the road construction. In 2016, the Arizona Department of Transportation began removing roadside memorials erected by the bereaved. “The point is, we want them to go in and really not be visited,” an ADOT spokesman told the Arizona Capitol Times. “They’re not to be having people pull over and tend them constantly.”

Remembrance, it appears, can be hazardous. ADOT has since modified its policy to removing only those that aren’t up to its code, which is geared toward making memorials as maintenance-free as possible and, somewhat ironically, less likely to distract drivers. Remember, but don’t notice.

During those drives, it was easy to lose perspective on how far I had left to go, so it was always a relief to reach Nothing. Then I knew I was getting somewhere.

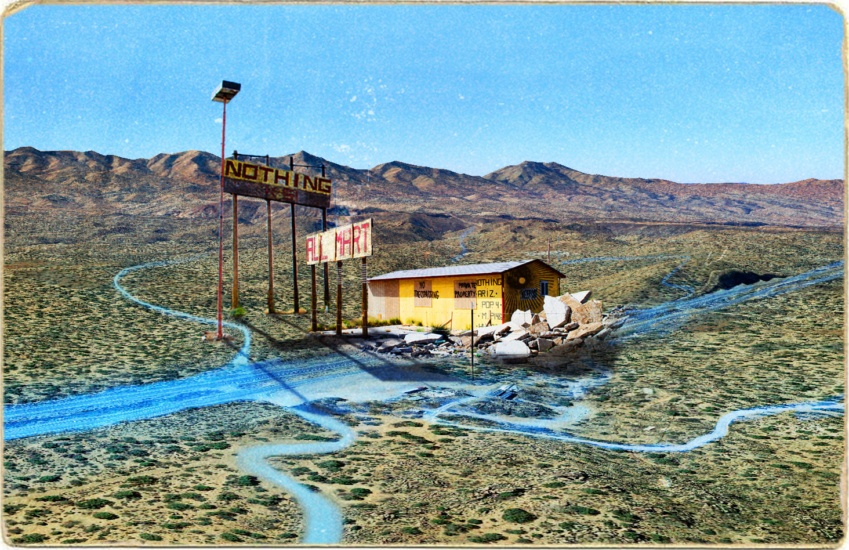

Nothing was mostly dilapidated outpost on the loneliest part of U.S. 93 in Arizona, with dramatically overpriced gas and washrooms for customers only and possibly free ice water, like Wall Drug. It was the only turnout for a while with more than a emergency call box and a steel-drum waste can. It had a rock and gem shop and a contextually comic sign that read ALL MART.

When I would drive by, it usually looked fringy and forlorn, less a rest stop than a dusty catch basin for desert refuse — broken-down cars and faded hand-painted signs amid the scrub. Currently it is marked on Google Maps as Isaiah’s Place. From the overhead perspective you can see what are possibly solar panels where the rock shop was. Zoom all the way in on the Street View image from 2009 and you can see proof that the police stop at Nothing.

I never stopped at Nothing myself — I usually got my emergency gas at the Chevron in Wikieup, about 25 miles away — but Nothing invariably sparked in me annoying trains of thought about its semi-ironic gimmick name: how the place was self-refuting; how in choosing to be Nothing it became more of something than Wikieup or Wickenberg. And I would invariably get mad at myself for falling for the dumb “Who’s on first”-ness of it, for the name working on me and getting me to think about it. Why is there something instead of nothing? How can you get something from Nothing? Does declaring something nonexistent actually affirm its existence? And so on. I hated how the proprietors of Nothing turned the flexibility and fundamental ambiguity of language into a tourist trap.

Recently I had Nothing in mind because I was reading sociologist George Ritzer’s The Globalization of Nothing, in which he decides to assign a new and completely counterintuitive theoretical meaning to the word. “In many, many ways,” he warns, “nothing as it is used here is in near-total opposition to the way people conventionally use that term. As a result, if readers do not make the definitional and broader mental switches required here, the conclusions they draw from this book will be totally different from, if not diametrically opposed to, those that I intend.” Okay, then.

It seems a strange choice to anchor a theoretical insight on a term you fully expect many people to misread and misunderstand, but such are the tempting paradoxes of “nothing.” Ritzer wants to use the word to signify the absence of difference among mass-produced or highly rationalized experiences, in which anything potentially distinctive or personal or of local character has been refined away, standardized. Ritzer’s idea of “nothing” is an extension of Marc Augé’s “nonplace,” allowing it to apply not only to places but to things and practices and people. In his view, any distinctive character in a thing creates friction that makes circulation and consumption less efficient, so things that are meant to be consumed at scale aspire to be “nothing.” Ritzer argues that “that which is nothing is more likely to be disenchanted, to lack mystery or magic,” and he cites things like Lunchables and Domino’s pizza as examples, contrasting them with gourmet meals and artisanal chocolate. He claims, for instance, that there would be little demand for a novel called Like Water for Lunchables.

But who wouldn’t want to read that? How one experiences the friction of distinctiveness is fairly subjective. Lunchables can be juxtaposed in ways that make processed food compelling and strange, and quirky “difference” can become its own kind of monotony, as with the decor of coffeeshops and boutique hotels (what Kyle Chayka has described as AirSpace) or with Instagram influencers. The folksy corniness of Nothing, Arizona, always struck me as a particular kind of contrived hokum, untempered by whatever species of desperation leads one to run a convenience store miles deep into nowhere. It was exactly what you would have expected it to be, in all its unlikeliness and remoteness.

The more I read about “nothing,” the more I found myself wanting to resist “something,” Ritzer’s examples of which — farmers markets, mom-and-pop businesses, diners, artisanal foods — all now seem like overfamiliar elitist clichés. There seems to be more mystery in the sheer fact of mass production, in implausible feats of standardization. And there is something uncanny in nonplaces that can make them unexpectedly haunting in their very familiarity. When I first saw a Wawa in Florida, I had this feeling.

It doesn’t look like Isaiah’s Place is currently in operation. What’s there now looks nothing like the Nothing I remember, though from the 2011 Street View image, it appears that its billboard-size sign is still up. Judging by a Google image search, the sign has become somewhat iconic. A few years ago, it featured prominently in Century 21’s viral marketing ploy on Father’s Day, in which you were invited to buy a piece of the Nothing acreage and so give your dad the “nothing” he probably asked for. Before that, someone called Pizza Man Mike, a nomadic chef who sold pizzas baked in his mobile wood-fired oven, tried to revive Nothing after the gas station shut down in 2006. (The highway improvements may have rendered the pumps less remote, less exploitable.) According to Pizza Man Mike’s own account, he ran afoul of some state bylaws and couldn’t stay in business there:

The Health Dept. refused to issue a Mobile Food License if I was Based in Nothing, Building, Planning and Zoning stated it was residental and need to apply for comerical and basicly start over. as Nothing existis in Nothing and the DOT wanted me to pave the whole front and maintain it as my right a way. With all this said an done , since I could not sell anything in Nothing, not even water without a heafty fine. It left me no choice but to leave Nothing.

Part of what makes Ritzer’s something/nothing continuum so confusing is that, as he somewhat grudgingly points out, people are just as likely to fervently pursue nothing as something — to prefer the certainty of fast food to idiosyncratic local restaurants, to prefer the efficiency and expediency of Starbucks, all those things that health departments and licenses help ensure, to the unpredictabilities of a quirky coffee shop. As the manager of another very Nothing-looking locale, the Fat Trout Trailer Park, once said, I’ve already gone places. I don’t want every cup of coffee to necessarily come with ersatz authenticity.

In Ritzer’s terms, Nothing was something, a singularity, but when I looked at Nothing on Street View, it didn’t feel uncanny or idiosyncratic at all, just anachronistic. Even the most unlikely places feel like nonplaces when assimilated to Google’s interface. You can’t even go where there is nothing to get away from digital capture, from the standardization with which Google is “organizing the world’s information,” making Nothing no different in certain respects from the Chevron down the road. Nothing’s name implied a time where you could really feel lost, far off the grid. Now you can find Nothing onscreen, observable from several different angles, from the comfort of home. It seems like a fitting memorial. Nothing exists in Nothing, as Pizza Man Mike says.