Ever since I was young, I have played games to escape. Being raised as the only child in a household filled with adults, I wanted something that could take me into fantastical worlds. I read choose-your-own-adventure books to pass the time, but as soon as I was able to get my hands on video games, I was hooked. At home, though, we didn’t have much money for a desktop computer, let alone a video gaming console. So many of the games I played were at the school library or at a friend’s house.

In these contexts, video games became cathartic, a release from the monotony of schoolwork and strict parents. The first game I turned to was Where in the World Is Carmen Sandiego? a role-playing educational geography game with a female protagonist. Playing a woman-identified character that was a problem solver felt joyful and empowering. When I led her in the right direction, I felt a transference that made winning all the more fulfilling.

Assuming control of games characters made to suit sexist stereotypes elicited resistance and complicity for me simultaneously

Eventually, while I was in junior high, I got a Nintendo Gameboy, and as much as I enjoyed playing Megaman and Tetris, the Gameboy’s significance for me went beyond the game-play: Games gave me social and cultural capital; they offered me a way to bond with friends. It didn’t require any particular shared talent or intrinsic knowledge — common ground was structured into the games. But not many girls I grew up with played video games or saw it as a release, or even as recreation. Meanwhile, as a teenager, I learned to play games that made me feel like one of the boys. I played Street Fighter until I had blisters on my thumbs. The perception that only boys played these games made me want to play them even more. This changed what video games meant for me: The catharsis they once provided began to be overshadowed by the gendering work they performed, both within and outside the worlds of the games.

Playing games became a way for me to navigate this engendering, to try to understand it as it was happening to me and my peers. How was gender performance incentivized? How was identification with characters and gendered perspectives built in to games, and could games be used to defy that?

In the games I once used for escape, characters tended to be trapped in various constructs. Some of these played explicitly into gendered stereotypes — rescuing princesses, for example. But others — kill as many ducks as possible, level up to beat the boss enemies — were ways to dress up the otherwise arbitrary incentives that make progress through a game possible. These formulas are basic to the idea of gamification, where incentives are used to guide behavior that has significance outside the world of the game. In Reality Is Broken, game designer Jane McGonigal offers Kevan Davis’s online role-playing game Chore Wars — which assigns experience points for real-life housework — as an example of how gamification inserts familiar narrative arcs into nongame situations to modify or control human behavior. She calls these “fixes.”

This approach has become commonplace, reaching a point where gamification is almost intrinsic to the way we socialize. This is clear not only in the rise of social mobile games like Words With Friends — which mirrors the ways games helped me bond with friends as a kid — but also in the ways interaction itself is gamified within social media with various performance metrics.

But in the games I played as I grew older, like Street Fighter and Tekken, gamification was not the only way behavior was being governed. The characters were no longer necessarily stuck in those stock narrative formulas and constructs, but they were still trapped in gendered expectations. Video games still overwhelmingly pander to the male gaze. For example, I was ecstatic to learn about the creation of a Filipina character for Tekken 7 only to find out she was a stereotypical, hyperfeminized, light-skinned character named after iconic Filipino political leader, José Rizal. (The character’s name is Josie Rizal.) Playing such games and assuming control of characters made to suit sexist stereotypes elicited resistance and complicity simultaneously due to the masculinity and brutality associated with many fighting games. But it seemed possible to consent to the game’s incentives while resisting the attitudes about gender they reproduced.

If gendering and gamification could be seen as separate forms of control within video games, they seem to have been brought together by recent trends in heteronormative dating: Apps like Tinder, OkCupid, and Bumble use data, algorithms, and location information to give date-seeking a game-like apparatus. Swiping left or right until you get a match or having to wait until your match messages you is all part of a larger game of capturing attention and “winning.” This methodical approach to dating corresponds closely with the discourse of pick-up artistry, which explicitly depicts the process of finding sexual partners as a game. In fact, Neil Strauss’s 2005 book about pick-up artists was aptly titled The Game.

Pick-up artists believe that with practice and persistence, as with any other kind of game, if you play long enough, you will “win”

Pick-up artists like Roosh V, who retains a cult following and writes regularly about neo-patriarchy and the fallacies of feminism, suggest how pick-up artist rhetoric is inseparable from heteronormativity and conservative politics. Roosh V, not surprisingly, is a Trump supporter, and Trump’s comments to Billy Bush in an infamous video that circulated during the campaign epitomizes the predatory attitude of pick-up artists toward women: “You know I’m automatically attracted to beautiful women. I just start kissing them, it’s like a magnet. And when you’re a star, they let you do it. You can do anything. Grab them by the pussy. You can do anything.” In 2012, Roosh wrote something very similar: “I want to be in a place where if I step outside and take a deep breath, pussy will come. I want to walk in a huge club and be the most desirable man who women compete over. I want zero-effort pussy of the most beautiful girls I’ve ever had in my life. Maybe you’re laughing right now that I’m dreaming, that this place doesn’t exist, but I believe it does, and sometimes belief is all it takes.”

Roosh is describing a positive-visualization fantasy, which is common across various forms of self-help, including one of Donald Trump’s inspirations, Norman Vincent Peale. “Like his positive-thinking spiritual master,” Chris Lehmann notes in this article from the Nation, “Trump clearly believes that the manic repetition of what he desires to be real, in both the pecuniary and political realms, is enough to make it a reality.” Roosh believes this works in the sexual realm as well: With practice and persistence, as with any other kind of game, if you play long enough, you will “win.”

If pick-up artistry is just an expression of how games in general work — structuring goal-oriented imaginative visualization, reinforced by repetition, until one can level up — to what degree is the sexism of pick-up artistry derived from gamification itself? Can the same sorts of gamified incentives be used in a different kind of context to subvert the pick-up artist’s game? What are the sexist assumptions built in to who is doing the playing and who is getting played?

The Game: The Game, created by media artist Angela Washko, addresses these questions, using pick-up artists’ seduction scripts to create a dialogue-driven interactive text game. It is an extension of her previous project Banged, which, in her words, was “a webpage of interviews, yelp-style text reviews of Roosh’s sexual performance and pick-up game and much more from the women he refuses to acknowledge beyond the notch” and ended up including an interview with Roosh himself. “Roosh’s framing of these women makes it clear that he believes he is manipulating them to some degree with his game,” she explained at Animal New York in 2014. “However I imagine their experiences are much more complex and much more interesting than Roosh’s one-sided story.”

The estrangement of PUA language in The Game: The Game allows players to recognize how often they have been brought to play this game in the world

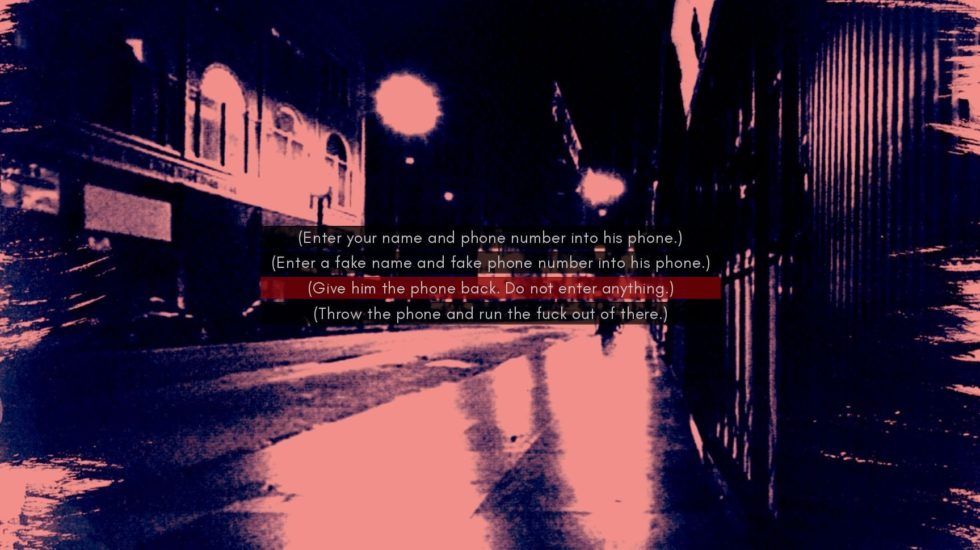

Upon launching The Game: The Game, you are given fair warning about the sort of environment you are about to enter: Sinister horror film-like music, composed by Xiu Xiu, and unsettling images, like female mannequins tinted with a blood-red filter, begin to appear. The format of the game sets come-ons drawn from the typical scripts of pick-up artists against grainy, foreboding images, and players must choose how to respond. A play-through is organized into chapters, each of which confronts the player with a different well-known pickup artist. Their tactics are fairly consistent, including “negging” (subtly insulting a woman to play off her insecurities), “pawning” (using one woman to demonstrate one’s supposed desirability to other women), and just plain persistence.

It’s not the sort of game you would want to play again and again, and that is part of the point: to problematize the kind of repetition that structures other games. But the estrangement of PUA language from its customary context also allows players to focus on its strategic logic and form, and perhaps recognize, disturbingly, how often they have already been exposed to such rhetoric — how often they have been brought to play this game in the world.

The player’s voluntary participation in Washko’s game becomes allegorical, raising questions about the nature of consent — in how both PUAs and games in general operate. A line from the game gets at this purpose: “And at least your evening wasn’t derailed by pick-up artists, pick-up artists in training and the subtle complexities of distinguishing performed behavior designed to seduce women into quick sex and polite conversation among strangers.” The nature of the previous statement speculates an evening that has been pre-empted as opposed to re-enacted. It was after constant rejection of the PUA’s advances that I found incredibly exhausting.

My play of Washko’s game was an uncomfortable and anxious ordeal. Some of the text triggered instances of when I have been harassed or blatantly degraded by men. But I continued, and even played multiple times to experience different outcomes. It helped make the neo-masculine lifestyle of the pick-up artist much more legible to me. This kind of repetition was no longer in the service of gamification — I wasn’t trying to level up in any conventional sense — and it cut against the gendering that other kinds of video games tend to try to naturalize. Instead it served to expose how neo-patriarchy and hypermasculinity trap pick-up artists in their own game, left mouthing their constricted, gender-conforming scripts.

When games rely heavily on gamification, this can sometimes leave status quo assumptions about narrative arcs in place, but when gamification is taken on directly, an explicit aspect of the game’s content, space is opened up for ways to challenge those arcs. Game designers can make environments and characters that are not merely pretenses to trigger incentive structures. They can articulate and mediate experiences, helping players gain perspective on a diverse range of possibilities. That massively multiplayer games such as World of Warcraft have been repurposed for conceptual and performance art suggests how even the most mainstream games, and not just art projects like Washko’s can be made to speak to ideas beyond their gamified objectives, and how they can affect behavior without having to resort to gamification-style behaviorism. Gamification is not as sexist as pick-up artists make it out to be. It can be turned in on itself to critique gendered modes of objectification that reduce other people to bosses to defeat or even princesses to rescue.