When I go back home, I’m often taken aback by how people in the street just … talk to each other. The point of these casual conversations is not informational or operational — if you wanted, you could easily extract more reliable factual knowledge from the internet with a phone. They aren’t meant to be productive or facilitating, either. These conversations aren’t about anything, and that is their point. They aren’t governed by signal-to-noise ratios. These exchanges are only social — they make sense only as a way of treating the other as a person rather than as a source of information.

This makes a striking contrast with the sort of functionalized, machinic communication that is often demanded in workplaces. From a management standpoint, knowledge workers (who might be responsible for synthesizing the content of meetings, summarizing brand impressions on Twitter, reporting the weekly progress by different teams, and so on) would ideally communicate as computers do, with unambiguous ones and zeroes. Messages would have a single, clear “signal” meaning that would be the same in any context, among any co-workers, and the social component of communication — anything that seems to exceed a strict functional purpose — would be understood as only so much “noise.” The best workers would be processors who can effectively extract information from one source and encode it into the text of an email or slide deck with no superfluities, wasting none of the receivers’ time on anything that doesn’t directly and explicitly serve a business purpose.

The stripped-down, functionalist, antisocial logic of workplace communication has begun to color broader social interactions. Other people appear as conduits to information rather than ends in themselves

To try to minimize noise and maximize speed along those lines, some workplaces have sought to impose narrower communication channels. Some of this is a matter of business-school lessons in professional communication that become codified as workplace norms: Send a follow-up email with exactly one anecdote from the initial conversation (more only if you’re angling for a big favor), then the specific ask, followed by a cheerful sign-off. But the narrowing can also be implemented technologically: Gmail, for example, suggests phrases (especially for openings and signoffs) that standardize and simplify this aspect of “writing,” providing options that are pre-certified as “average” or appropriate. One can imagine the niceties of business communication becoming so rote and automated as to become completely superfluous, vestigial: Economically precarious millennial professionals optimized for efficient workplace exchange would become frustrated trying to respond to older colleagues’ emails, where the relevant information is interspersed with human irrelevancies, like saying “hello” and “goodbye.”

The technological aides that smooth and constrain communication may not be left behind at the office, however. They could colonize our broader social interactions as well. It may seem as though optimizing information-oriented workplace text exchanges would make them contrast more sharply with social communication — or that it could save us from having to engage as fully in rote work conversations and preserve more energy for open-ended talk. Crystal Chokshi recently described how Gmail’s predictive text recommendations may appear to reduce workload by reducing the time spent typing out emails; in practice, though, she argues, the time “saved” is spent sending more emails. A similar logic could affect all forms of communication; as it is routinized and automated, it will spark a feedback loop in which automatic messages metastasize in responding to themselves.

Not only that, but many of us find that we cannot so neatly divide our lives into separate spheres and maintain a clear line between work and nonwork communication. The functionalizing tendencies spill across that hazy border. Text (whether it is routinized, automated, or artificially enhanced) plays a key role in landing “independent contractor” roles. It plays in the sales pitches for ourselves that many of us must make across various levels of acquaintance. It allows us to participate in semiprofessionalized social media exchanges and aspire to become part of a “creator economy”; it figures into letters of recommendation and other application processes that are increasingly high-stakes. The temptation to streamline and enhance that kind of communication with technology is strong, even though it may devalue such messages in the long run.

But the stripped-down, functionalist, antisocial logic of workplace communication has begun to color my broader social interactions in a different way: Rather than appreciating conversations with people in qualitative terms, as totalities that can’t be broken down into signal and noise, I find myself looking for ways to throttle the channel to a more instrumentally useful level. Other people then appear as conduits to information — Where’s the best pizza in town? How did you get a visa to stay in Berlin? What’s the job market like in your industry? What shows have you been watching? — rather than ends in themselves.

The pursuit of information narrowly conceived — treating acquaintances as apps or search engines — forecloses on other levels of conversation. For instance, a friend may give inefficient directions compared with a map app, but their directions will also convey affect, memory, glimpses of how they understand the world, all aspects that could potentially reinforce or clarify the friendship. The app eliminates all that, and such losses are cumulative. Extrapolate that across all the kinds of communication that apps and predictive text seek to render obsolete and social interaction may come to seem merely inefficient. We may lose sensitivity to other kinds of intentionality in our communication.

When Chokshi suggests that predictive-text apps “could remind you that you’re writing on the anniversary of [someone’s] mother’s death, and prompt you to acknowledge it,” I fear that this would devalue the chronologically based communication of intentionality. The case of Facebook’s automatic birthday reminders is illustrative. Remembering friends’ birthdays and giving them a call used to be a common way to communicate that you cared about them; it also opened up a high-density channel for further social communication. Now friends must defy the new norm of generic birthday messages on social media to seize on that opportunity, which changes the implications of the effort.

I can send a multi-line email thanking a friend for their birthday message, and neither of us can be sure to what degree the other was actually involved in the process

I can send a multi-line email thanking a friend for their birthday message, and neither of us can be sure to what degree the other was actually involved in the process. Such messages — despite potentially being identical to emails sent a decade ago — have now become more difficult to parse, not in terms of their information but their intention. Nothing can be reliably inferred from the fact my birthday was remembered or that I remembered to say thanks; no conclusions can be drawn from how timely the messages are. The words may be appropriate enough, but the emotional subtext has become far more opaque. By reducing the friction in birthday messages, automation has stripped them of the social recognition we actually want them to convey. It’s the thought that counts.

As more communication comes to be under suspicion of being automatic, we become obliged to expend extra effort to credibly convey intentionality. We must deliberately strive to come across as “thoughtful” rather than simply be thoughtful. Google trends data suggests that searches for “thoughtful” have been rising steadily over the past 15 years, which indicates the problem it increasingly presents. But thoughtfulness too has become automated: One of the pre-supplied options, when you review an AirBnB, is that the place included “thoughtful touches.” Thoughtfulness itself has become commodified and reified. Automation has managed to turn it into its opposite, thoughtlessness.

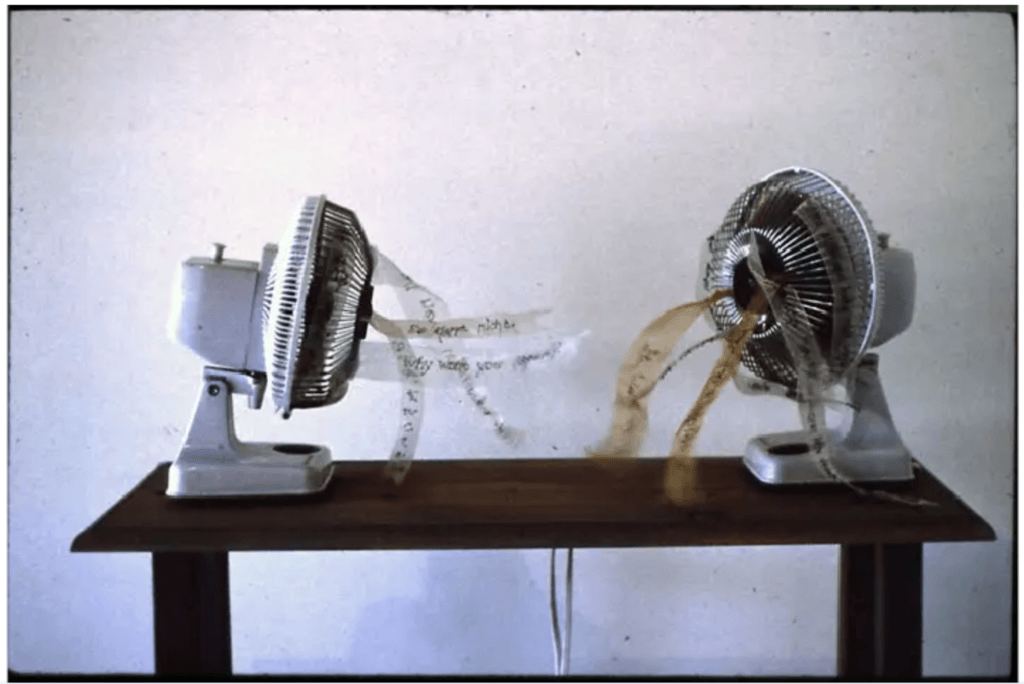

To restore intentionality to social conversation means deliberately reintroducing the bumps, the odd angles of ourselves that automated workplace communication and predictive text seeks to sand away. This means paradoxically trying to purposely add purposeless or “useless” qualities to conversations. Yet the bar on uselessness is constantly rising: The more our conversations are monitored and processed as data by machines, the more difficult it will become to introduce something that feels as though it came from outside that system — that feels like a computer could not have produced it for us.

Although we have been nudged and molded into more streamlined nodes in communication networks, humans have, to date, still been required for processing and creating human-language text. This barrier has recently been broken, however, with the development of high-quality text-generating models like GPT-3, the latest iteration of OpenAI’s series of text engines. It is the largest neural network ever, trained on an exponentially larger corpus of text data, including all of Google Books, a massive scrape of the web, and all of Wikipedia.

From the perspective of labor economics, GPT-3 is troubling. It provides competition to knowledge workers that could render their jobs moribund. Tasks like summarizing events for news articles, performing chat-based customer support, writing novel but generic political speeches are already being done by machines; the leap to the new uses made possible by GPT-3 is all but inevitable.

People who know each other well may be able to find alternatives, but digital textual communication between strangers would be further consigned to strict functionalism. Strangers will remain strangers

Wary of GPT-3’s potential use for online harassment or fraud, OpenAI restricts access and limits the range of its possible outputs. But the mere existence and reputation of GPT-3 poses a general threat to the textual communication of intentionality. Its capacity to further optimize and mimic communication along predictive, functional lines makes human social communication via digital text less convincing in general.

Take letters of recommendation: the best letters are personal and heartfelt, but it has also become essential that they be long — vague claims about how great the student is are easy to come by, but a lengthy letter that contains specific details is a costly signal that the professor spent time and energy creating the letter. With GPT-3, however, it may become trivial for professors to plug in a CV and some details and end up with a lengthy, personalized letter. In the long run, this would undermine the value of such letters to credibly communicate effort and sincerity on the part of the recommender.

But GPT-3 will likely have implications beyond those threats. Recently, MIT Tech Review reported on a Reddit bot secretly posting GPT-3 output on active text threads as if it were an ordinary human Reddit user: It encountered text, referenced its massive database of English language writing, and produced new text to post. Among the bot’s responses was one to a request for advice from anyone who’d had suicidal thoughts: “I think the thing that helped me most was probably my parents. I had a very good relationship with them and they were always there to support me no matter what happened. There have been numerous times in my life where I felt like killing myself but because of them, I never did it.” This response — supportive, generic, uplifting — was upvoted by other Redditors 157 times.

But if what comes across as “uplifting” is easily faked by a bot (one that can pass for having had suicidal feelings, no less), such messages may become increasingly suspect. The affective efficiency of content may indicate the absence of human concern rather than serving as an expression of it. It may start to appear that the only way to signal human intentionality on a Reddit thread is to veer away from what previous circumstances and human decency had called upon most people to do (and what machine learning models have learned to mimic). Then, only what is bizarre, cruel, profane, abusive, may come across as human. Evidence of this reactionary tactic is not difficult to encounter on the internet.

More promising is a push toward genuine novelty: playing with language by deconstructing words, adopting new slang that contorts standard grammar. In Patricia Lockwood’s recent novel about language and Twitter, the tweeters find joy in using the word binch, a word whose appearance might be unpredictable by machines so far. But generative text models can be rapidly and perpetually updated with usage trends. All digital communication encoded in human language can be fed into the next iteration of the model. Linguistic novelty might create brief spaces of freedom, outside the machine’s training data and thus distinctively significant to humans. But some of the most powerful entities in the world are dedicated to closing these gaps as quickly as possible. “Run me over with a truck”; “inject it into my veins”: that’s not a tweet, it’s an arms race — one we cannot win.

To encode intentionality in communication will increasingly rely on cues that seem to have escaped the system. People who know each other well may be able to find these alternatives, drawing on the trust and experience they already share. But digital textual communication between strangers would be further consigned to strict functionalism. It will be impossible to tell whether it was written by a human or a machine, so in those scenarios, it will no longer matter which is true. Strangers will remain strangers.

In order to address this condition, it may be necessary to admit that we sometimes inhabit the role of a machine. It’s no more cynical to accept a role as a node in an information network than to accept that our labor power is being mechanized in factories or in other rationalized means of production. There is no reason to expect one form of labor to be more “human” than another just because it centers on information and text. This admission might help re-establish the boundaries between functional and social interactions, and open communication to greater intensities that exceed the mere flow of information.