“What does your tweet mean?” This is one of the more chilling messages a person can receive, especially if they already feel as though they are too online. Though anybody who carries a phone with them is, in a sense, always online, only some identify with that as an identity — largely because we’re hyperconscious of how much time we spent on platforms like Twitter. So the question implies that maybe you’ve gone beyond simply using the internet, and are now just spewing nonsense. The best brains of a generation destroyed by memes, exploding, cosmic, galactic.

When “being online” feels like “being incomprehensible,” it can seem like a social and emotional dead end, a cul-de-sac with no other houses in sight. No wonder people increasingly feel the itch to leave the neighborhood altogether, and consciously shut out online. When should one consider this change? I was asked the question when I tweeted the following image:

To “get” this joke, one must know the context of “corn cob” and “binch” — respectively, a reference to a @dril tweet used to suggest that someone is trying too hard not to lose an argument, and a mocking variant on “bitch” developed to get around Twitter’s content filters. You must also have seen the specific tweet in which pundit John Stoehr, facing a veritable Space Jam’s worth of dunks, blithely asked about the meaning of both terms. And you must have seen the episode of Game of Thrones from which the screen cap is taken, in which the schemy character Littlefinger realizes he has been tricked into his own execution.

When “being online” feels like “being incomprehensible,” it can seem like a cul-de-sac with no other houses in sight

This is a high threshold to get a joke. And even if you get it, the joke may not be that funny to you. In a sense, the confluence of hyper-specific prerequisites to understanding the joke is the joke. In the same way a sitcom gag relies on a set of conventions for how people act and conversations unfold, online jokes often rely on combining references in an order that surprises.

But are such jokes worth the trouble? Given that online speech — including allusive, self-referential memes — is shaped by corporate platforms for profit and has contributed in open and obvious ways to our current societal turmoil, might there be some intrinsic benefit to construing oneself as a person who isn’t online, who steps away from all of it and implicitly (or explicitly) brags about how little they know? Put another way: Is being “extremely online” — that is, being invested in maintaining a fluency in online tropes — inherently toxic?

There are many reasons a person can wind up being extremely online. It could be that they’re antisocial, a troll, or simply like showing off their knowledge. (This is annoying, but not necessarily worse than the other million ways a person can be annoying.) Or it could be that, like many people in gig-based creative fields, they feel a crushing obligation to self-promote or make industry connections. Or it could simply be that they have found a community online. In any case, very online people find themselves entering a carnival of language where different games, booths, and attractions beckon, each with their own chaotic energy.

How to make sense of this sensory overload? If we are going to “be” online, how should we do it? Turning the cacophony of online discourse into intelligible sound is a task well suited to the work done by ordinary-language philosophy, a branch of thought that developed from the late work of 20th-century philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein. It starts from the premise that speech — written or spoken, images and memes — does something rather than represents something. In his book How to Do Things With Words, ordinary language philosopher J.L. Austin offers the example of a wedding: When someone says “I do,” they aren’t describing something about the world, they’re changing something about their lives. The same is true of promising, daring, and retweeting.

Some words name things, of course, but that’s just one of an incalculable number of things you can do with words. Memes are not deposits of exclusionary knowledge and archaic references — at least, they’re not just that. They don’t just name things; they also do the work of creating and collapsing contexts. They don’t reproduce a world but bring one into being.

If the meaning of the word comes from the way it is deployed rather than some ineluctable “truth” about the world it is supposed to capture, then the relevant question is not what does this word mean, but what does this word do here? What is its use? This approach allows us to more effectively examine important questions, like “What is binch?”

Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations, itself a meme-like series of hard-to-parse prose poems, is littered with concepts equally difficult for newcomers to grasp. What does Wittgenstein mean by “language-game” or “family resemblance”? What is to be “corn cobbed”? In particular contexts, even familiar words can suddenly seem meaningless, or worse, give us the wrong idea. In Revolution of the Ordinary, Norwegian philosopher Toril Moi gives the example of Spanish bullfighting jargon, in which ordinary Spanish words are repurposed to indicate minute bullfighting nuances. To translate such language, a Spanish to English dictionary is of no help — you have to be imbricated in the technical use of the language. The same might be said of Know Your Meme, or Urban Dictionary, or overly serious essays explaining memes at-length.

A meme — an endlessly replicable joke format that becomes repeated to the point where it loses any original meaning outside of the repetition itself — is a condensed form of “use” as ordinary-language philosophers understand it. Moi describes use as “a practice grounded on nothing” and whether you love or hate Chewbacca mom, that’s a rather apt description of her existence. “Dictionaries struggle to keep up with use, not the other way around,” Moi writes, a sentiment that will ring true to anyone who has had to read a story about a dictionary declaring some months-old piece of internet slang the “word of the year.” These words and phrases often have legible uses before they are pressed into service by different online communities. They simply acquire new ones — or, it might make more sense to say, the same set of letters becomes a different word, a different move in the game.

But the point here is not to say that being up on “online” requires traveling to some alternate world and learning totally new norms distinct from those of “real” conversation. It’s that online conversation is like all conversation, which consists of what Wittgenstein calls language-games. In Philosophical Investigations, Wittgenstein gives the following examples of language-games: reporting an event, speculating about an event, forming and testing a hypothesis, making up a story, reading it, play-acting, singing catches, guessing riddles, making a joke, translating, asking, and thanking. Here are some additional examples: dunking on someone, signal boosting, virtue signaling, shitposting, pulling receipts, reading someone for filth. Many of these language-games originate in gay or black American vernacular, which adds “appropriating” to the list of games already being played. And while these language-games originate online they can also be played in offline spaces, as anyone who has interacted in the flesh with friends they connected with online, laughed at the opening strains of “Never Gonna Give You Up” in a bar, or wordlessly directed a friend’s attention to an image on their phone will know.

“Online,” then, is more a cluster of related language-games than a single overarching one capable of being catalogued. In fact, the use of the word online as a noun makes fun of the idea that it could possibly be one mode of speech or one place you could visit. I use the phrase “extremely online,” but even this will mean something only to a segment of people who spend a lot of time using specific online platforms in specific ways. But you don’t have to recognize yourself in the term to be playing these language-games.

To learn a language-game, even as an observer, is an ongoing matter of understanding specifics, complexities, and nuances. It requires, Wittgenstein insists, a “training of our attention as much as of our vocabulary and style.” For better or worse, being extremely online is a form of this training. It is to be attentive to the interplay of these different language-games, to put in the time to start to understand how they are played, and to learn how to speak to other people in different contexts. Like it or not, we’re not always there when the internet calls, but we’re always online.

Being extremely online means being sensitive to these language-games in action and knowing how to effectively spoil them

It’s possible to be good at being extremely online, and it’s possible to be bad at it. It’s possible to suffer unhealthy side effects from being extremely online (as many, many people will tell you), but it’s also possible that it could blend seamlessly with the rest of your life. This will largely depend on other, individual factors about your life beyond the internet. As Wittgenstein says, “explanations come to an end somewhere.”

What, then, does it mean to “get” a meme? And why should it embarrass anyone?

Consider the internet language-game of deploying the word nice in response to any possible appearance of the number 69. (Nice.) A practice that began as an intentionally buffoonish reference to the existence of the sex number, replying to 69 with “nice” has become almost totally divorced from the original joke or sexual context of the number, to the point where it’s as conventional as blessing someone when they sneeze — a practice with religious roots that is now simply part of standard etiquette. As Wittgenstein puts it, “If I have exhausted the justifications, I have reached bedrock and my spade is turned. Then I am inclined to say: ‘This is simply what I do.’” (Nice.)

That explanation, however, probably did nothing to make the practice at all funny to someone who doesn’t already get it and enjoy it. Trying to explain why something is funny often drains a joke of all comedic value; on the internet, where something can strike thousands of people as funny one minute and painfully trite the next, trying to force explanations is lethal. Is a meme simply a fad, where instead of carrying around pet rocks or going glamping, we feel giddily seized by the thought of staring at someone’s shoes and asking, “What are those?” In many cases, the context of who is using a meme changes the landscape for other people interested in using it — consider how quickly a meme dies when a branded account starts deploying it or, God forbid, your parents. Being extremely online is a willingness to speed up this process of churn, to tear through all of the possible permutations of one game in order to exhaust it and move on to the next one.

Understanding the blur between the way words are used in highly specific online language-games and the way they’re mistakenly deployed by dupes has also become crucially important political work. “Astute” political commentators are fond of observing that polarization has created “different realities” based on the demands of whatever tribe you happen to belong to. But it’s not that hyper-partisanship has made people “disregard” facts — language never had the ability to contain facts of the kind your dad’s friends publicly mourn in Facebook posts.

This, specifically, is what the “battlefield of ideas” implies: the fight over which use of certain phrases will come to dominate. Terms like “identity politics,” “intersectionality,” “political correctness,” and “neoliberalism” all originated in the academy with specific uses, articulating particular frames for social conditions and in turn suggesting potential political responses. But these terms have been repeatedly appropriated, watered down, and deliberately stripped of their efficacy by right-wing sophists and terrified white liberals, who have pressed them into service as often-sarcastic, intentionally obfuscating scare words, where the original use has been drowned in the fear and confusion the word is intended to provoke. The academic who insists on the “real” meaning of these terms may be technically right, in a sense — but they are also missing the point. Being extremely online means being sensitive to these language-games in action and knowing how to effectively spoil them.

Consider the phrase “free speech,” which ostensibly implies some sort of inalienable right to expression but has been manipulated until its primary deployment in certain contexts is to express fear of and belittle college students. When it comes to understanding what “free speech” means to those getting marching orders from white supremacist message boards, it won’t do to insist that that term “really” means this or that, and that they are misusing it — that is simply willful ignorance about what is actually happening.

That it’s possible to ignore your phone for an hour and come back to a wildly transformed landscape of expression is a testament to how easy it is to find oneself adrift

Imprecision abounds in public dialogue, but it’s not quite right to say language is “misused” by those with whom we disagree. Instead, we must understand how they are using words and expose the repellent belief system they are attempting to mask or launder. We must invest our energy not in loudly insisting that everyone stop getting it wrong and use “correct” definitions, as if that will be inherently binding to everyone who uses language. As Moi argues, “The more adept I am at ferreting out your hidden ideological agenda, the better I demonstrate my grasp of the finest nuances of your way of speaking. The more astute my critique, the better it demonstrates that we share both the words and the worlds we are fighting over.” The closer words are shared and the deeper they are held, the harder it becomes for their users to back away from the things they are doing when they speak.

Applied to the nonsense rampant in the public sphere, Moi’s project feels like a breath of fresh air. To internalize an ordinary-language philosophy approach is to lose interest in much of what passes for discourse — the constant insistence on speaking as I speak, doing as I do, memeing as I meme. Being online, and understanding the ways that we’re all constantly online whether we want to be or not, opens us to the winds of change and makes it difficult, maybe impossible, to impose a “correct” meaning on the words and phrases we deploy. You can only try to make your usage more compelling, more immediate to others, all while remaining opening to the ebb and flow — what Moi describes as the “constant transformation” of language.

The mere fact that it’s possible to ignore your phone for an hour and come back to a wildly transformed landscape of expression is a testament to how quickly language-games can move without us, how easy it is to find oneself adrift. But that doesn’t mean we should split memeified online language off from “real” language, or that offline speech should be taken as an effectively stabilizing counterpart to the fluidity of online speech. To think of the world without online language is to think of it without the letter “e” — you certainly could live that way but it wouldn’t be easy to navigate, and at the very least, you would be denying yourself a clear view of things. We must instead put the work in everywhere to understand how language use is changing and how we can participate in that process, which is precisely the use of one of my favorite memes: the expanding brain.

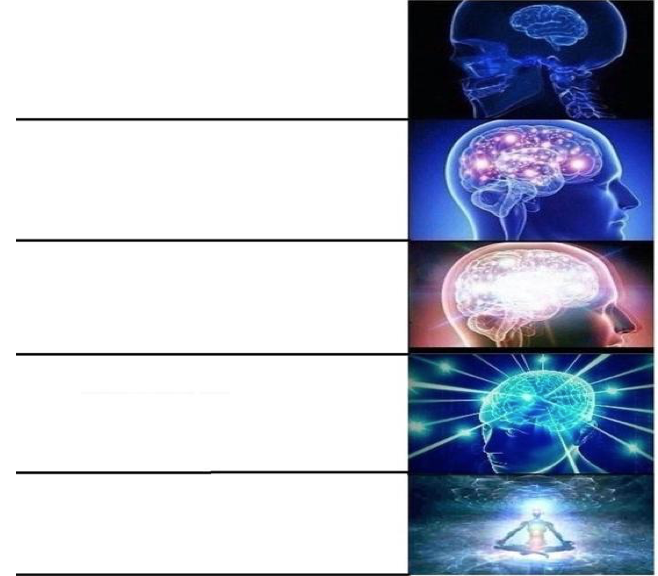

For the uninitiated, this is the expanding brain meme template:

According to Know Your Meme, the popular version of the expanding brain template originated with this set:

Like many instances of the meme, this one is used to mock a tendency to over-intellectualize online. In the spirit of ordinary-language philosophy, though, it’s worth asking what else the meme can do. Where it originally was about comic escalation into absurdity (“whom’st”), the best uses of the expanding-brain meme make real arguments — albeit with a form of distance.

The existence of online jokes that require an extraordinary level of context to grasp trains us to re-consider what we think is obvious

The meme typically represents the progression from a basic, uncomplicated opinion — this TV show is good, I like this film, etc. — through an increasingly complex series of ideas about the subject and then back to a gut-level, earnest, simple reaction, as in this example about following artists in social media. But all the components of the expanding-brain meme can be (and often are) true at once. This allows it to, for instance, condense a reasonably sophisticated criticism of American capitalism into a single image. And it accommodates problematic affinities: Its format corresponds to how it can be true that, say, the Indiana Jones franchise is frequently racist and proud of its colonialist bent and that watching Harrison Ford blow stuff up and shoot Nazis can be pleasurable.

It’s not a coincidence that a frequent target of this meme is the academization of discourse around gender and sexuality. It’s a sort of hero’s journey through language and the mind, from an initial unmooring from the way we have been raised and trained see the world, through a dizzying array of ways of thinking about it that can be useful, clarifying, and/or nonsensical, and finally back again, transformed and capable of changing the world. The penultimate brain — the wokest, most byzantine, most self-assured brain — is unable to grapple with this infinite texture, the way many things can be true at once, that any given slab of language is going to grasp at best a piece of the reality.

But this doesn’t mean we should double down on returning to the earliest world of single, unitary “truth,” one that somehow existed before some mysterious force sent us into a “post-truth” world. There was never any “truth” like that to begin with, at least not in the way its most strenuous defenders think. Instead, moving through what we perceive as layers of description allows us to return to the original context, armed with firmer and more clear-sighted knowledge. This path may seem circuitous, but it puts us in a better position to see and to do things with our words.

Similar meme formats can act as funnels for the play of contexts, the texture we must grasp if we want to learn anything. They allow us to see the world not as an inflexible product of laws that can be discovered by careful reading and observation but as a series of intersecting clouds and constellations, what Wittgenstein might refer to as “family resemblances.” The existence of online jokes that require an extraordinary level of context to grasp continually trains us to pay attention to the way that context is demanded even in using what might appear to be commonplace language, forcing us to consider what we think is obvious and what is only obvious to us — and that what might seem obvious might really be totally obscure.

Playing language-games that originate online has many effects, but playing with an openness to everything people attempt in those games makes it difficult to hold on to only one of those pictures, only one brain, freeing us to begin thinking about how no thinking occurs in isolation. It’s okay that not everything conforms to a given idea of what it’s supposed to be, even if that rule-of-thumb definition has “worked” for most cases in the past — especially because what “works” is often “common sense” used to prop up systems of oppression and inequality. We simply have to be willing to admit that each case might, in large part, be its own case.

If it seems dubious to claim that memes as a form do important philosophical work and do it better than many who are paid to produce long-form opinions, consider the source: Wittgenstein, who allegedly said that “a serious and good philosophical work could be written consisting entirely of jokes.” At the outset of Philosophical Investigations, he writes that most of the problems of philosophy emerged because “a picture held us captive.” He could not have known another picture — a near-endless series of pictures — could free us, and that those pictures just might be stock photos of an abstracted human form moving through the cosmos, unceasingly seeking enlightenment.

This essay is part of a collection of essays on the theme of EXTREMELY ONLINE. Also from this week, Rina Nkulu on dressing for the internet.