BAD METAPHORS is an ongoing series that takes a critical look at the figures of speech that shuttle between technology and everyday life. Read the rest here.

I don’t have the bandwidth for that.

People say this and often they mean something like, “I don’t have time for that.” They might say this to their boss, about a work project they don’t really feel like they can add to their metaphorical plate. Or else maybe it’s in the context of a romantic relationship that’s getting a little more serious than they originally thought it would, that’s coming with some of the snarls inherent to relationships, like feelings and fights, and it’s all starting to take up a lot more time than expected. Or perhaps they say it to a friend about another friend, who has been going through the same sad break-up for what feels like too long, whose daily phone calls are running up against the limits of their schedule and sympathy. Or rather, their bandwidth.

The expression is not exactly about time, or not about time in the sense of space on the schedule, which likely could be cleared or changed if it needed to be. Of course, this is not always true, but one of the strange realities about our time is that we often can rearrange it or add to it so that we can squeeze another something into the waking hours of our day. This is a reality that capitalism exploits; it’s something bad friends and boyfriends ignore. “Bandwidth” allows you to opt out of the great sleight of hand of modern life: “making time.”

Bandwidth, the literal kind, can refer to a number of things, but it encompasses boundaries. When used in computing, “bandwidth” refers to a fixed rate of data transfer — a capacity, really. It is the maximum amount of data that can be transferred from one point to another over a computer network or an internet connection in a given period of time. It is expressed as a rate: bits per second, or megabits per second. Generally, bandwidth is a fixed amount; you can pay for more or less of it.

“Bandwidth” allows you to opt out of the great sleight of hand of modern life: “making time”

Though bandwidth was of great concern in the early days of the internet — a higher bandwidth had a lot of marketing power — these days, most people paying for wi-fi in the United States have pretty high bandwidth. (Broadband, as they say!) Indeed, it’s probably not something you think about very often, unless you’re running up against its limits — say, for instance, when you’re streaming a video and it’s freezing. Perhaps someone else on your wi-fi is also watching Netflix, and the network is clogged up by the volume of data it’s processing in real time.

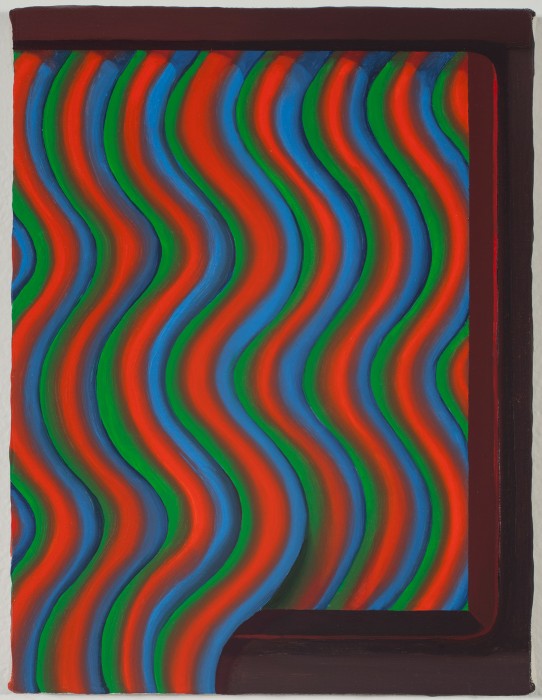

In electronics, bandwidth can also mean the distance between the upper and lower frequencies on a spectrum of transmission; in radio, this would be the “width” of electromagnetic frequency range at which a station can operate. You can look at the United States Radio Frequency Allocation Chart, and see the spectrum of frequencies chopped up by the FCC into brightly-colored and pastel bands of different widths. Many of the bands look squeezed, razor-thin and almost layered on top of each other; others are big chunks of blue or pink.

This visual is useful in thinking about bandwidth, the metaphor: Many of our lives probably feel a bit like this spectrum, sliced not only into strips of time on Google Calendars, but extremely nebulous things that manage to take up abstract “space” — emotions, physical energy, a tangled web of friendships, anxiety. “Bandwidth” becomes a catch-all of sorts for the immaterial obstacles we face in doing what we feel we’re supposed to. Perhaps our commute was longer and more trying than usual, or we got a phone call with some surprising bad news. This might chip away at some of our emotional bandwidth. We may not quite know what it is, but we know when we’re running out of it.

We almost never talk about “having the bandwidth” for something; it is usually in the negative. The “bandwidth” metaphor plays on the concept of hard limits, set and managed by forces outside our control — fate, or, in the literal sense, internet providers or the FCC. It is inelastic, and also not our fault. It allows us to do a bit of tacit blame-shifting, which can be useful (a way to say “no” that’s more failsafe than “I don’t have time”) and can also be permission for selfishness (a way to turn away from a friend in need because we simply don’t feel like it). In the gentle shrugging off of blame, “bandwidth” as metaphor becomes a useful distortion, since there is no regulatory body assigning us an emotional frequency spectrum. There is no wi-fi company we can pay for more or less of it. We manage our own bandwidth. We set the limits. And that’s a lot of pressure.

In the gentle shrugging off of blame, “bandwidth” as metaphor becomes a useful distortion, since there is no regulatory body assigning us an emotional frequency spectrum

Another, old technological metaphor that’s newly in vogue is “burnout” — by the gig economy, the 24/7 news cycle, student loan payments, being constantly plugged in. Metaphors of “time” and “space” seem of little use in setting boundaries, as we’re asked to do more with less; admitting to the limits of our own capacities feels a little like failure. “Bandwidth” presents a workaround: having “limited bandwidth” is an objective, if regrettable, state of affairs, about which there is little to be done. Most of us can still remember our frustration at, say, the stutter of a still-downloading movie, mid-scene, and the total futility of any attempt to make it go faster. It’s out of our hands.

Using it comes at a cost, however: By using a word for the transfer of data to describe our inner lives and capabilities, even in attempting to care for ourselves, we are extending the logic of computing into our lives. When we discuss feelings and relationships in terms of “bandwidth” we are treating them like megabits of information. At work, the phrase “I don’t have the bandwidth” might be a handy way of pointing out, rightly, that we deserve better compensation for what we’re asked to do. But applied to the basic stuff of living — feelings, friends’ problems — it turns personal responsibilities into indistinguishable units of space. At best, they become something to be crunched, finished at the highest rate possible, like the upload or download of a file.

Personal “bandwidth” implies that we must move through the world like machines; and that experience is, to use a different metaphor, something that we need to process, and process, and, process, up until we hit some kind of capacity. It implies that beyond that capacity, we have nothing left.