I don’t know what first enthralled me to Elton John, but from the first time I saw him — singing “Goodbye Yellow Brick Road” on the Muppet Show, in a sparkly piano-key bowler hat — I just liked him. I was five years old. My Mom bought his albums for me whenever they turned up at garage sales and my Godfather lent me his four-CD box set, which my Dad taped onto cassettes that I fell asleep to every night. My old school notebooks are full of drawings of his face and stories in which we are friends; the day I finally needed glasses was as significant as that of my first period.

The adults in my life were encouraging, but I didn’t know any fans in my age cohort. I never joined his fan club or went to see him live; he was like an imaginary friend or, in my agnostic household, a God — when I was alone, he was there, and when I thought to myself I talked to him. The initial spark of attraction might have been arbitrary, but I have words now for the Elton in my mind’s eye: Gap-toothed and grinning, playing dress-up in clothes a five-year-old girl might dream of, tarting up all the would-be shortcomings that set him apart from the average rockstar.

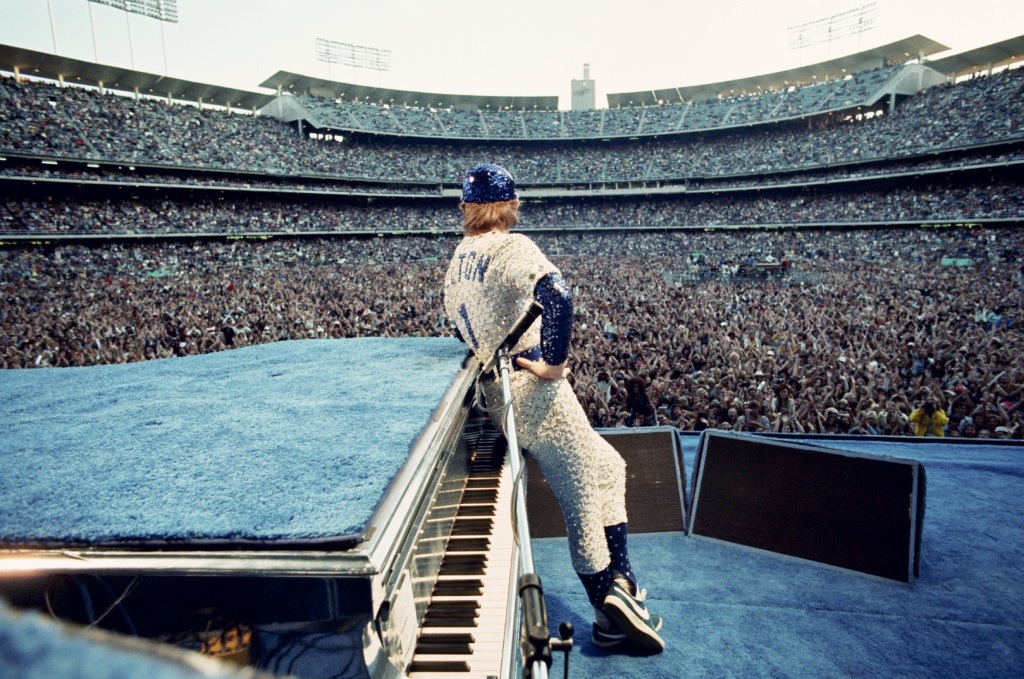

I think Elton is one of the most stylish people in history, though most people I’ve known have disagreed; so it has been validating to witness his recent inauguration as a style icon. Gucci creative director Alessandro Michele based an entire collection on Elton’s costume archive, and designed the looks for his ongoing Farewell Yellow Brick Road tour. Rocketman, Elton’s long-awaited biopic, was released to much more fanfare than I’d expected, benefiting commercially, and critically, from its proximity to Bohemian Rhapsody. Today, Elton John is relevant: a gay genius who conquered a macho genre and endeared a global audience to high camp, whether they knew what to call it or not (“Gay pride wrapped up in telling gorgeous metaphor,” Hilton Als wrote on his Instagram). He is an inspiration to the awkward and otherwise uncomfortable in their skin: a non-emaciated, late-blooming, four-eyed, prematurely balding kid from the working class, who overcame his shyness through absolute garishness. The Met Gala’s “Camp” theme was indirectly in his honor, though as many have noted, there’s nothing campy about being straightforwardly hot and rich.

This revival has felt both exciting and dissonant. I have no intention of seeing the film — Taron Egerton, who plays him, seems like someone I’d walk away from at a function feeling drained and somehow insulted; it makes me nauseous to hear the old hits rendered with jangly Spotify chimes. Seeing Elton praised in Gucci’s ad copy makes me feel an odd blend of vindication and resentment. I’m happy for him, and for anyone reconsidering their opinion of his work, but I’m used to him feeling like mine.

My discomfort with all this fanfare seems a little bratty — a holdover from the obscurantist attitude I bought into as a teen, wherein the rarer the taste the more distinction it conferred. At worst, this pose was a sort of counter-elitism, adopted often by people who were insiders to the dominant culture but felt unfavored by its hierarchies. It also arose from a valuation of the legwork involved in finding the music you wanted to hear back when it was limitedly available — you had to care enough to seek it out, and seeking it out put you in company of other people who cared, too.

It’s not collectivity I’m after, but a version of privacy

The fact that Elton John is not obscure by any measure hints at some other impulse at work here. We tend to intuit fandom as something collective — usually the term refers not to the state of being a fan, but of belonging to a community of people who are fans as well: loving the artist is a primary qualification, but just as important is learning the conventions through which that love is shared in common. My own experience of fandom has always worked in reverse: It’s not collectivity I’m after, but a version of privacy.

The fan relationships I’ve built with my favorite musicians run deeper than most of my friendships. Music accompanies you where friends don’t — it’s with you in moments of total solitude, and it provides an amniotic base for thoughts and feelings you haven’t yet articulated. A side effect of growing up with headphones and portable players is that music is part of your life as it happens, and an index for your memories ever after.

It’s hard to know exactly why a given artist appeals to you, but explaining that connection to yourself is a bit like reading your astrological chart — a process of self-definition through a set of coordinates that offer a great deal of interpretive leeway. The affinity itself is an identification that feels like a zodiac sign is supposed to, in the sense of a cosmic likeness: a preverbal understanding that this person represents “your people,” in the deepest abstract — that you share a shade of perception that overcomes space and time. To confront a divergent interpretation can be jarring; it can prompt an identity crisis.

The more formalized these connections become — the more they assimilate to a network — the more distanced I feel from my own attachments. That feeling of affirmation that comes with being a fan, the ineffable sense of belonging in human history, is replaced by a language that isn’t mine, and a set of social dynamics too particular to a time and place. At a time when we are constantly being sorted algorithmically, by preferences and tendencies we might prefer to think of as arbitrary, or to not think of at all — and when social platforms encourage us to reduce ourselves to thumbnail reductions of our values and interests — the more important it feels to hold my loves close to me. Like any long-term relationship, the artists of whom I’m a fan remind me of who I am and where I’ve been when I’m at risk of losing touch with myself.

This past winter I decided, after a lot of handwringing, to pay exorbitantly for Elton John tickets. It was the first, and likely the last time I’d see him live, and I felt a strange, existential nervousness beforehand. The closer I got to Madison Square Garden, though, the more I realized how excited I was, in spite of myself, to finally be among fellow fans. Not for any imagined sense of kinship, but for the brief feeling of raw, shared enthusiasm, a rare joy that any attempt to conjure tends to squeeze out of reach.

A side effect of growing up with headphones is that music is part of life as it happens, and an index for your memories ever after

The show was thrilling, and mortifying: Elton, the old pro, knew exactly what we wanted, and gave it to us; when someone gives me what they know I want, it tends to make me self-conscious about wanting it to begin with. I was glad to have avoided the regret of not having gone. My only disappointment was how alone I felt in the flush of really being there. For most of the casually dressed Boomers in attendance, the concert seemed as mundane as any other post-dinner engagement. Of my entire row, I was the only person dancing.

A couple of months later I was searching tour dates for Jorge Ben Jor, a Brazilian musician whose career transcends genres and eras, and whose genius and import I can’t do justice to in a few lines (from Caetano Veloso: “the artist Jorge Ben is the denizen of that utopian country beyond history that lives within all of us, that we all have the duty to build”). I noticed he was playing a festival in Porto, and since I have a friend in Lisbon I decided to book a ticket. I’ve been a fan of Ben Jor’s for nearly half my life, but my enthusiasm for him developed in a bit of a vacuum: He’s iconic in Brazil, but less well known in the North American cities where I’ve lived. I read the few books I could find in English that discussed his social and cultural context and legacy, but I never learned Portuguese. I made a little fan’s nest out of scraps of knowledge and the glue of my emotional attachment.

When my friend and I arrived at the festival grounds there was almost no one around the stage. We found a spot at the front, while a crowd filed in slowly around us. When Ben Jor came on, I screamed and cried and hopped against the audience divider — every song he played was so meaningful; I just didn’t know the words. As the awe subsided, I turned and saw just how huge the audience had grown; my friend and I were now two among thousands. Everyone was just as excited as I was; everyone was singing along.

The country was Portugal, not Brazil, and the fans in attendance represented just one cross-section of his global fan base. But to be among so many people who loved him, too — who could sing along in his language — was exhilarating in a way that vaulted me beyond my own limited sense of intimacy with his body of work. It felt like falling back in love, in a sudden, jarring way, with an old companion, to remember how vastly their world expanded beyond what felt familiar.

Like any relationship, there are different ways of loving your idols. One is a companionate love that forms as their work becomes a feature of your life; this is how homes are built, but you risk submerging their context in your own. Then there’s a love more difficult, vital, and fortunate — one that takes you beyond yourself, toward the light of a perception that broadens your world and will never be yours.