In 2013, the New York Times published an opinion essay under the headline “I Know What You Think of Me,” in which the writer Tim Kreider describes having once been CC’d on an email between friends that appeared to be making fun of him. “It is simply not pleasant to be objectively observed,” he says. “It’s like seeing a candid photo of yourself online, not smiling or posing, but simply looking the way you apparently always do, oblivious and mush-faced with your mouth open.” Being unguarded against the judgement of others is a humiliating affair, Kreider reasons, but the vulnerability of being visible to one another is a necessary prerequisite for building true connection. Or, as he concludes, “If we want the rewards of being loved, we have to submit to the mortifying ordeal of being known.”

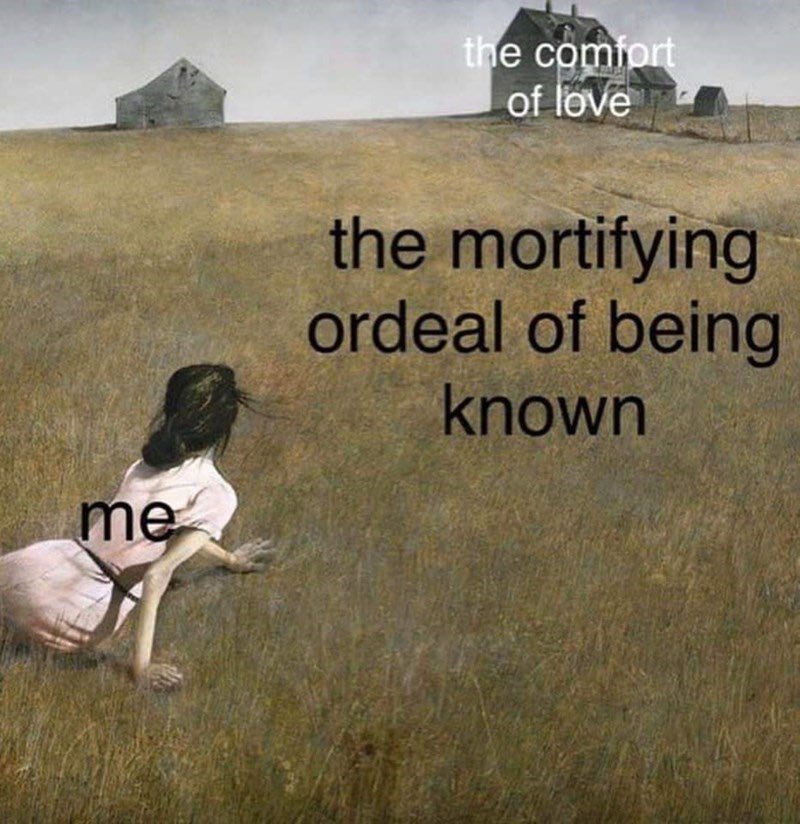

Like most pieces of writing on the internet, Kreider’s essay quickly faded from memory. Then, five years later, someone posted that final sentence, stripped of context, to Tumblr. The post went viral, circulating across the site; users eagerly latched onto new grist for the shitposting mill and began churning out memes, inserting “the mortifying ordeal of being known” into image macros from Arrested Development, Lord of the Rings, Parks and Recreation, and the Andrew Wyeth painting “Christina’s World.” The meme eventually spread to Twitter and then to TikTok, and as it did, the original quote became abstracted — while some posts still riffed on the phrase in full, others referred simply to “being perceived,” as in, don’t perceive me. Viral examples include: “It’s a HIPAA violation to perceive me,” “that’s enough being perceived for today,” and “in order to fuck marry or kill me u would first have to perceive me and I am not about to let that happen.” The joke is rooted in a creeping claustrophobia born of universal anxieties about our messiest and most tender selves being exposed to others, a fear that has shaped the Western canon from Kafka to Plath to reality television. For an increasing number of people on the internet, however, this ambivalence has engendered a fantasy, not of being perceived in an idealized, Instagram-ready form, but of not being perceived at all.

Where the early internet was once a space onto which futuristic ideals about life detached from the physical self were projected, it is now a very different environment, one in which our appearances, mannerisms, and manifestations are constantly observed and analyzed with continuously heightening stakes. Perhaps the most obvious example is that of facial recognition technology, which has long been used by law enforcement and increasingly appears in public spaces such as airports, as well as the Detroit roller skating rink that refused entry to a Black teenager based on an inaccurate facial scan in July. When the pandemic forced schools and workplaces to operate remotely, algorithmic surveillance promised to shore up the gap in productivity and compliance as well. Until backpedaling due to public outcry in April of 2020, Zoom offered an “attention tracking” feature that indicated to the meeting host if an attendee clicked out of the window for more than 30 seconds; for students in remote classrooms, “A.I. proctoring” programs like Proctorio and ExamSoft monitor eye and body movement during test-taking, flagging those who look away from the screen too often, or not often enough, or display any quantifiable body language outside the recorded standard deviation. And Facebook’s newest venture, an immersive VR workspace using Oculus headsets, brings things full circle, overlaying skeuomorphic representations of our bodies in an environment where their physical presence has been made obsolete.

The omnipresence of social media has acclimated us to being constantly photographed for a particular type of public display

At the same time, the omnipresence of social media has acclimated us to being constantly photographed for a particular type of public display. As the intended audience of our photos has expanded, and their context shifted from individual images to pieces of a larger project of documentation or expression (i.e, the Instagram grid), the conventions of these digital platforms have not only reshaped standards of beauty, but the ends toward which it is pursued. Our public appearances are now constructed, through cosmetics, body modification, and plastic surgery, with the gaze of the camera as much in mind as much as those around us in real time, if not more so — photos, after all, last forever. Opting out from showing yourself online is certainly possible for those whose livelihood doesn’t depend on a public-facing digital presence (an ever-dwindling segment of the population in the age of side-hustles and creator economies). But for those who came of age with the social internet, a long trail of digital annals lingers behind us; while I shudder to think of the photos of me from eighth grade that exist somewhere in the ether of my atrophying Facebook network, the sobering reality is that there’s no shortage of current eighth graders whose entire lives have been documented on Instagram. Log off all you want — throw your phone in a river, if you wish — but somewhere, someone will still be looking at you.

In the past few years, a concern has emerged among some cultural critics and observers about the possibility that we are living in a dissociative age. “Dissociation,” in its traditional psychiatric context, refers to a symptom of various mental illnesses, characterized as a distressing and, in some cases, debilitating feeling of distance or absence from one’s body. In the past decade or so, however, the term has been picked up within the ballooning wellness industry, where it is situated opposite the goal of “mindfulness,” a state involving awareness of the body and the sensations surrounding it. In an essay for Buzzfeed titled “The Smartest Women I Know Are All Dissociating,” which went somewhat viral on Twitter in 2019, Emmeline Clein argued that the popularity of media like Phoebe Waller-Bridges’s show Fleabag and Kristen Roupenian’s 2017 megahit short story “Cat Person” evidenced a trend in which women, particularly the very online, become emotionally distant from their bodies as a response to depression or discomfort.

She presents this dissociation as a foil to the early 20th century concept of “female hysteria” — women feeling too little as opposed to too much — though they might be better understood as different points on the same historical timeline of white-middle-class-woman malaise. Clein cites a variety of viral tweets, some quite similar to your average “don’t perceive me” meme. Similarly, a feature about the popularity of recreational ketamine in New York Magazine includes a bit of hand-wringing about “our dissociated moment.” Dissociation even pops up in “Shouts and Murmurs”: “What is countering all-enveloping discomfort in public spaces by pretending that ‘everywhere is a spa’?” a comic called “Meditation or Dissociation: A Quiz” asks (answer: dissociation).

The “dissociation” of memespeak is an acknowledgement of the phenomenon’s strategic dimension, sharing a vision of the internet free from compulsory body awareness

Dissociation is often mentioned in this context with a timbre of reproach; within the gnashing gears of the wellness industrial complex, it is sold to the urbanized white middle class as an unhealthy habit, like smoking or forgetting to drink water. But dissociation is not a vice — it’s a strategy of the subconscious, meant to remove the conscious mind from a potential overload of discomfort when a true escape cannot be made. If the psychiatric definition of dissociation and the wellness industry-infused version are each pathologizing visions, the “dissociation” of memespeak is perhaps something different: an acknowledgement of the phenomenon’s strategic dimension, as a coping mechanism aimed against the claustrophobic overload of being seen constantly. Through this lens, the flurry of “don’t perceive me” memes appear almost tactical, sharing among them a vision of the internet free from compulsory body awareness.

I didn’t expect changing my Twitter profile picture to a photo of the actor John Reynolds to elicit an emotional reaction within me. And yet, scrolling down my timeline with his face staring back at me instead of my own in the corner of the screen, I felt a palpable shift, as if my body was suddenly lighter and my joints all somehow realigned. Soon, I’d replaced my profile pictures on other social media; I even changed my icon on Gmail and Zoom, unsure of how to explain why the avatar for my ostensibly professional accounts was a photo of the hot guy from Search Party staring bug-eyed into the distance, but compelled still by that feeling of lightness. A few months ago, I decided to begin writing under my initials, rather than the first name by which everyone calls me. In the only photo of me that currently appears in a Google search, my face is cropped down the middle and partially obscured by my hair.

Online, I’ve curated myself into an intentionally nebulous shape, though like most people my age, the details of my history remain scattered in the cyber cosmos for any skilled Googler to find. This isn’t anonymity, nor is it really dissociation, but rather, a cousin of both — a sort of refraction through which I’ve negotiated with my own ambivalence about being perceived. Certain strains of wellness or body positivity rhetoric might characterize this as a retreat, signifying a regression in self-confidence or self-integration. But the less I’m looked at, the clearer it seems: I feel least constrained, most like myself, when I am unseen.