On a muggy Saturday afternoon in June, I sat in a dimly lit party space in Ridgewood, Queens, listening to a collection of sex workers, trafficking survivors, and allies describe how a piece of legislation had begun to decimate their community. Some told stories of workers who’d left the safety of their homes to work on the street, or young women who had disappeared or died in the weeks following the law’s enactment. A number of women spoke passionately about the necessity of decriminalizing sex work.

The primary incentive for the meeting in Queens was SESTA-FOSTA, a recently passed law that positioned itself as an antidote to online sex trafficking. SESTA-FOSTA’s numerous proponents claimed that by dismantling Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act and making it possible for the government to hold websites and hosting companies accountable for any sex trafficking that took place on their platforms, they’d be able to shut down sex trafficking online. But in the weeks since the law’s passage, the main result had been the shuttering of consensual sex workers’ online communities, advertising boards, and safety resources, changes that drove sex workers out onto the streets in search of clients and made them far less safe in the process.

The other reason that brought us into that room was Suraj Patel, the Congressional candidate hosting the town hall. Although pornography and sex work had become increasingly mainstream topics over the past few decades, politicians remain extremely conservative on the topic. D.C. has never been on the cutting edge of cultural change, and its attitudes towards sex work have remained generally negative over the past few decades. While the lingo may shift from curbing obscenity to protecting public health, the sex trade is generally treated as the enemy. Tellingly, SESTA-FOSTA was a broadly popular, bipartisan bill, attracting the support of some of the most liberal politicians in Congress (including, yes, Bernie Sanders). Patel had been one of the few candidates to take a stand against SESTA-FOSTA, and for sex workers who were used to being ignored and derided by the government, he seemed like the best chance of getting someone with reasonable views on sex work into the halls of power.

Twitter, Reddit, online commerce, and working remotely may seem like social trends wholly unrelated to sex work, but sex work has been integral to them

But as I sat there, listening to the experiences shared, it struck me that another underlying force had led us all there: Over the past two decades, the internet has radically transformed almost every aspect of sex work. It’s shifted the industry’s demographics and altered what the work entails; it’s made the work easier to get into while creating new challenges that have made it vastly less profitable. And all the while, it’s given sex workers a platform to advocate for themselves, without having to rely on a third-party messenger — a powerful tool that has dramatically shifted how we talk about sex work and sex workers. Twitter, Reddit, online commerce, and working remotely may seem like social trends wholly unrelated to sex work — but they’ve been integral to sex work, just as sex work has been integral to them. The internet, in shifting the way we live and work and relate to one another, has fundamentally altered the place that sex work resides in within our society.

In the spring of 2001, I was a college sophomore, one with a habit of browsing a new crop of alternative, or “alt,” porn sites that were quickly developing a loyal fan base. Like many adult entertainment neophytes, I’d long believed that porn performers hailed from a narrow and highly specific sector of the population. Mainstream movies and TV shows had told me that they were primarily blonde, with bodies heavily modified with implants and surgical reconstructions, their skin a uniform shade of artificially induced tan. The few porn magazines I’d happened upon did little to challenge that stereotype, so I bought into it without question, taking for granted that porn performers were nothing like me.

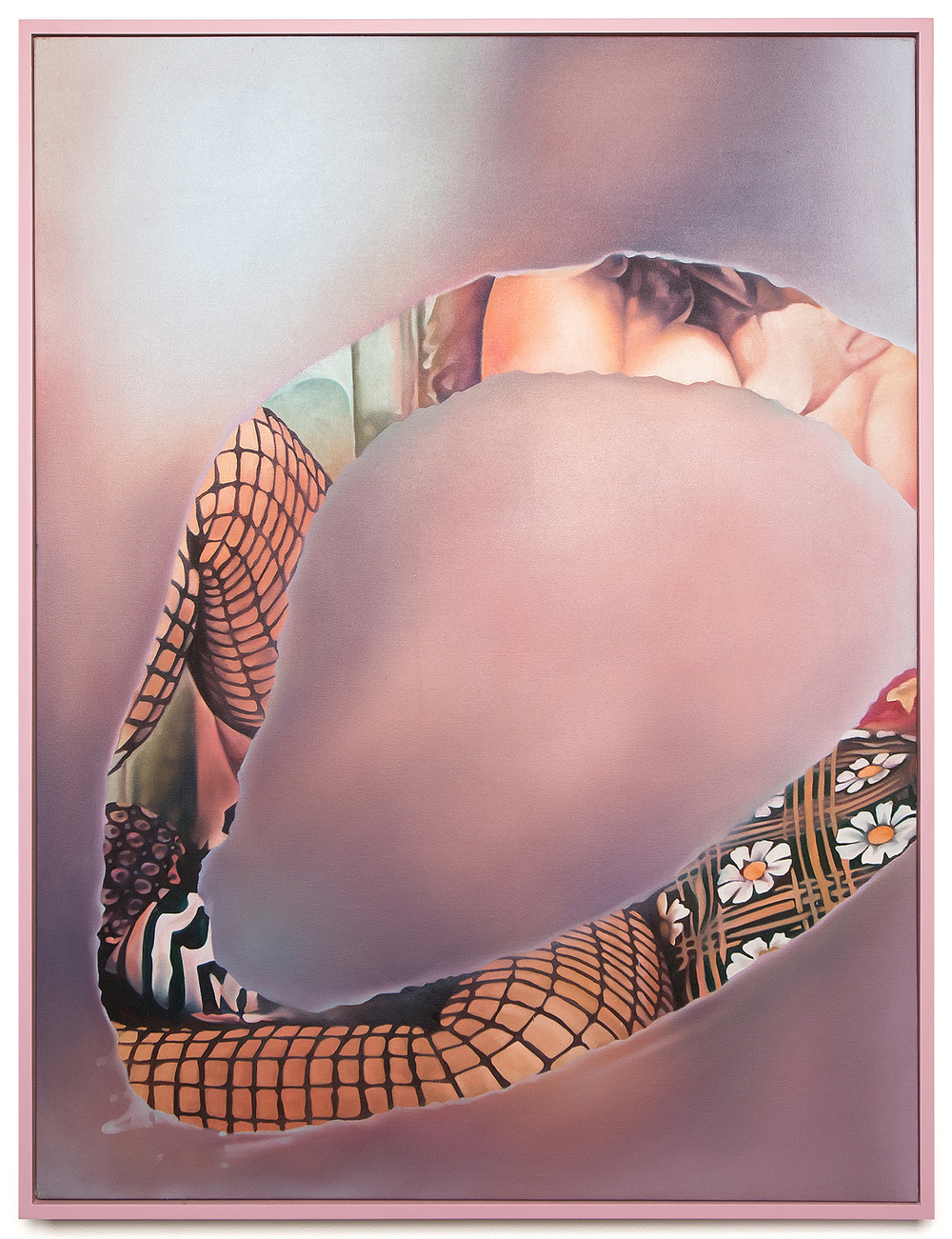

But the sites I saw as I was browsing the XXX internet blew that conception wide open. Whatever diversity the women of Playboy or Penthouse may have lacked was on full display online, where it was impossible to hold fast to the belief that a porn performer had to be one specific kind of person. Online, it was easy to access images of many different kinds of people engaged in erotic acts; it was easy to see that sex workers were not one specific thing.

The sex industry has always been more complicated and heterogeneous than outsiders have given it credit for. Long before the internet transformed the industry, companies like Femme Productions and S.I.R. Video were offering porn consumers a different take on eroticism. To claim that the internet invented feminist or queer or alternative porn would be deeply ahistorical; the internet’s ability to facilitate search rendered these niche branches of porn more visible to consumers.

Yet it’s undeniable that, in addition to highlighting the diversity that was already there, the internet made sex work a more appealing occupation for many people who might not have considered it in an earlier era. The internet lowered the barriers to entry and, for some people, made sex work feel safer. While it’s always been possible to shoot a porn movie independently, getting distribution and building a fan base was a complex and expensive process prior to the internet; for most aspiring porn performers, it was easier to head out to Los Angeles and hope an existing porn company would show an interest in casting you. The internet changed that equation: You could upload your work to the internet and let the fans come to you.

Porn wasn’t the only form of sex work that underwent a change. Cam networks offered a digital alternative to strip clubs and peep shows, giving anyone with a webcam the opportunity to perform for tips without ever leaving their bedroom, or having to convince a club manager they were worth taking a risk on. Similarly, escorts found themselves with entirely new methods of connecting to clients. Instead of going to work for a madam or on a street corner known for its association with sex work, it was now possible to post an ad on an escorting message board, sort through the potential clients who responded, and vet them for safety concerns using online tools, all wholly independently and from the comfort of one’s home.

As indie sites demonstrated that there was an audience eager for content that had long been viewed as too niche by mainstream studios — whether it was heavily tattooed performers or androgyny or performers eager to brag about the books they’d read — those mainstream studios began to adapt, diversifying their lineup of talent and shifting the public’s idea of who exactly could be a porn performer, of what it meant to be a sex worker. The stereotype of the blonde, artificially enhanced sex worker lives on in shows like Parks and Recreation and Saturday Night Live, but a quick glance at the front page of Pornhub reveals that’s hardly the only kind of person you find in porn.

By late 2008 I was running Fleshbot, then a Gawker Media-owned blog that had helped to class up coverage of sex and porn, bringing wit and feminism to the field. Fleshbot had been founded in the fall of 2003, in an era when porn — and especially online porn — was easy money. You didn’t even have to create your own content to get rich off smut: A number of small fortunes were created by merely curating content licensed from other people, or creating a site full of affiliate links and collecting a commission. The thrill of being able to access porn at home without having to make awkward small talk with a video store clerk was an intoxicating feeling, one that compelled people to open their wallets.

But by 2008 it was clear that we were entering a new era for the adult industry, one where lucrative pay sites were rapidly being supplanted by free tube sites, many of whom lured in audiences with pirated versions of their competitors’ product. A decade later, the effect this shift had on the consumer side is readily apparent. For many, pornography’s status as a freely available commodity is taken as a given; the idea of paying for porn is a foreign one even to some of the most XXX-obsessed consumers. Less discussed, however, is what the surge in free porn did to the people on the other side of the camera, and how it transformed a formerly lucrative career into an okay-paying job that many need to pad out with other hustles and side gigs.

Online, it was easy to access images of many different kinds of people engaged in erotic acts; it was easy to see that sex workers were not one specific thing

Performers who’d been shooting several times a week found themselves cut back to several times a month, with no indication that their shooting calendars would ever be fully booked again. There weren’t a lot of ways to make up for lost income. Sure, the most popular performers might be able to cross over into the mainstream, landing acting gigs or getting book deals or speaking engagements. But not every performer held the mainstream appeal of a Sasha Grey or a Joanna Angel, and for those who’d yet to acquire that cachet, the options were rather slim.

Stigma against porn and sex work makes it challenging for anyone who has ever been involved in the adult industry to secure mainstream work, a difficulty that only increased once the internet made porn performers’ backlogs easily — and permanently — accessible. In 2008, cafeteria worker Louisa C. Tuck resigned after her former career as Crystal Gunns became public knowledge; in 2011, CNN citizen reporter and substitute teacher Shawn Loftis was fired after being outed as the ex-porn performer Collin O’Neal. Porn performers who’d spent years being naked on the internet were fully aware that one Google search was all it might take to get them outed at a new, non-porn workplace. When facing a steep drop off in bookings, many preferred to seek out other forms of sex work in order to make up for lost income. For some, escorting seemed like a natural extension of work that already involved exchanging a sexual performance for money.

None of this is to say that the internet created a direct connection between escorting and porn. There have always been sex workers who have dabbled in both trades, whether they’re primarily porn performers who enjoy connecting with fans on the side, or primarily escorts seeking a bit of advertising and a bump in prestige from appearing in porn. But ever since Freeman vs. California rendered pornography legally distinct from escorting in 1988, some industry members had sought to play up that distinction, reinforcing a questionable hierarchy in which porn performers were more prestigious, or at least more socially acceptable, than their escorting peers.

As the realities of post-internet sex work both increased the economic incentive to escort and decreased the barriers to entry, that artificial distinction began to fall by the wayside. Some performers held on to the idea that escorting was somehow beneath them, propping up what many sex workers refer to as “whorearchy.” But others rejected the idea that one form of sex work was more legitimate than the other, and as the distinction became less pronounced, the sex work community became more united.

In the summer of 2015, human rights advocacy organization Amnesty International announced its intention to come out in support of sex work decriminalization. The decision resulted in predictable backlash, most notably an open letter signed by a number of prominent feminist activists and celebrities, whose opposition was rooted in the conviction that sex work is fundamentally exploitative, a belief that has defined certain corners of the feminist movement since the inception of feminism itself.

Yet Amnesty International’s announcement also found support from many sources — including, surprisingly, from many mainstream media outlets. As someone who’d been covering the sex industry for almost a decade at this point, it was stunning to see publications like the New York Times putting forth pieces that were tacitly supportive of sex workers. I’d spent years of my life arguing that sex work was not an inherently exploitative industry, that it was something people could consensually opt into, and now, suddenly, I was surrounded by other prominent voices making the same case.

There were, presumably, a number of factors that had led to this shift in public discourse: increasingly liberal attitudes towards sex, for one, and the decades of labor that activists had put towards destigmatizing sex work, but I couldn’t shake the feeling that somehow the increased, and increasingly vocal, presence of sex workers on social media had been a significant contributor. Sex workers have always been the most effective advocates for their own rights, and social media was presenting them with a massive platform for their advocacy.

Sex workers joined social media for the same reasons everyone else does: to find community, to connect with fans, to self-promote. For sex workers looking to increase their income, platforms like Twitter offered a way to potentially generate revenue, by directing fans to their premium content or advertising their cam shows or giving a heads up when they were going on tour. Fans, in turn, were drawn in by the promise of XXX content and the chance to get closer to their favorite porn performers and other sexy stars. But mixed in with the sexy content were glimpses into the actual lives of sex workers, which presented a powerful counterargument to the long standing stereotypes about what it meant to be a sex worker. Subscribe to a sex worker’s social media account, and you might get some titillation, but you’ll also get pictures of their pets, news articles they’re reading, and witty commentary on current events; posts that chip away at the stereotype of sex workers as two dimensional creatures only capable of thinking about sex.

When Obama came into office, the administration ended the Bush era fixation with obscenity prosecutions and byzantine records keeping laws that had made the adult industry a prosecution-prone line of work. But a new legal threat cropped up, this time at the state and local level. Throughout the early 2010s, multiple attempts were made to pass legislation that would mandate the use of condoms in pornography shot in California, a political fight that took sex workers’ online activism to a new level. Proponents of these bills (which included Measure B, Proposition 60, and AB 1576) argued that they were motivated by a desire to protect porn performers’ health and safety. But porn performers, who’d long relied on an extensive STI testing protocol to keep themselves safe on set, saw the move as nothing more than censorship intended to cripple an already ailing industry — and, in the process, make porn performers more desperate and less safe.

As sex workers pushed back against these measures, many industry members harnessed their online platforms for political activism, using their social media accounts to explain why mandating condoms in porn would do more harm than good. When Californians voted no on Proposition 60 in November 2016, it was evident that activists in the adult industry (who’d lost a similar fight over Los Angeles’s Measure B just four years before) were successfully wielding their political power.

As SESTA-FOSTA came up for a vote, the online political activism that had been honed through fights over condoms on porn sets went into action once more, with sex workers taking a stand to explain why a bill that positioned itself as anti-trafficking was actually poised to decimate consensual escorts, porn performers, and all manner of people engaged in sex-related work online. Hashtags like #SurvivorsAgainstSESTA urged Twitter users to call their representatives and ask them to vote against the bill.

SESTA-FOSTA’s opponents were ultimately unsuccessful — the opportunity to back a bipartisan bill, and say they were taking a stand for trafficking victims, proved too tempting for most members of Congress. But as a swell of anti-SESTA-FOSTA articles resonated through the media, it was clear that sex workers were being heard, even if the people in power weren’t always listening.

The internet created the environment that led to that sex worker advocacy meeting in Ridgewood, Queens — by shifting the demographics of sex work, by breaking down the barriers between the different factions of sex work, by amplifying sex worker advocacy and creating a broader base of mainstream support for sex worker rights.

It also led to that meeting in a much more literal sense. Weeks before we all gathered together to chat with Suraj Patel about sex work, one of the town hall’s organizers had responded to a tweet from Congresswoman Carolyn Maloney championing SESTA-FOSTA.

Maloney, like other supporters of the bill, knew that the internet had changed sex work. But from their distant perch, they saw only that it had made sex work more visible; and, applying longstanding stereotypes of sex work as inherently exploitative, assumed the internet had made it worse. By enabling the government to shut down sites like Backpage and encourage the shuttering of Reddit forums focused on sex work, SESTA-FOSTA may have made the sex trade less visible on the internet. But the conclusion that many Congressional representatives came to — namely, that pushing sex work underground somehow reduces rates of nonconsensual sex work — was based in ignorance and a persistent unwillingness to have their preconceptions challenged by the facts. Digital resources didn’t change these attitudes, only the methods by which they were imposed. But they also offered new ways to fight back.

Angered by Maloney’s smug, self-assured take on the bill, the organizer tweeted a response encouraging someone to run against her in the upcoming primary. That tweet eventually connected the organizer to Patel’s campaign team, an introduction that resulted in the town hall — which, in turn, was primarily promoted through social media. Although Patel lost the election, the town hall was still a historic moment in sex worker activism, and the energy I saw in that room has already been channeled towards promoting other politicians who’ve taken a stand against SESTA-FOSTA, like Democratic rising star Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez.

The internet transformed sex work in ways that helped sex workers and ways that harmed them, in ways that opened up economic opportunity and ways that shut it down. It’s difficult to quantify the overall impact, but there’s no denying that the in the past 20 years, the industry has radically been reshaped. And the community that has been created by those changes isn’t going anywhere any time soon.