Fame-shaming has long been a feature of the celebrity-industrial complex. Throughout the 20th century, gossip magazines, tabloid TV shows, and lurid tell-alls cashed in on the misdeeds of famous actors and musicians. Though a handful of celebrities seemed to capitalize on their anti-establishment reputations, the “stars behaving badly” trope (as Lieve Gies dubs it in this paper) has typically superseded any particular star-persona. Rather, in spotlighting celebrities’ wrongdoings, media outlets have served as moral arbiters, reinforcing social sanctions by identifying norm transgressions, especially those linked to gender, race, and class.

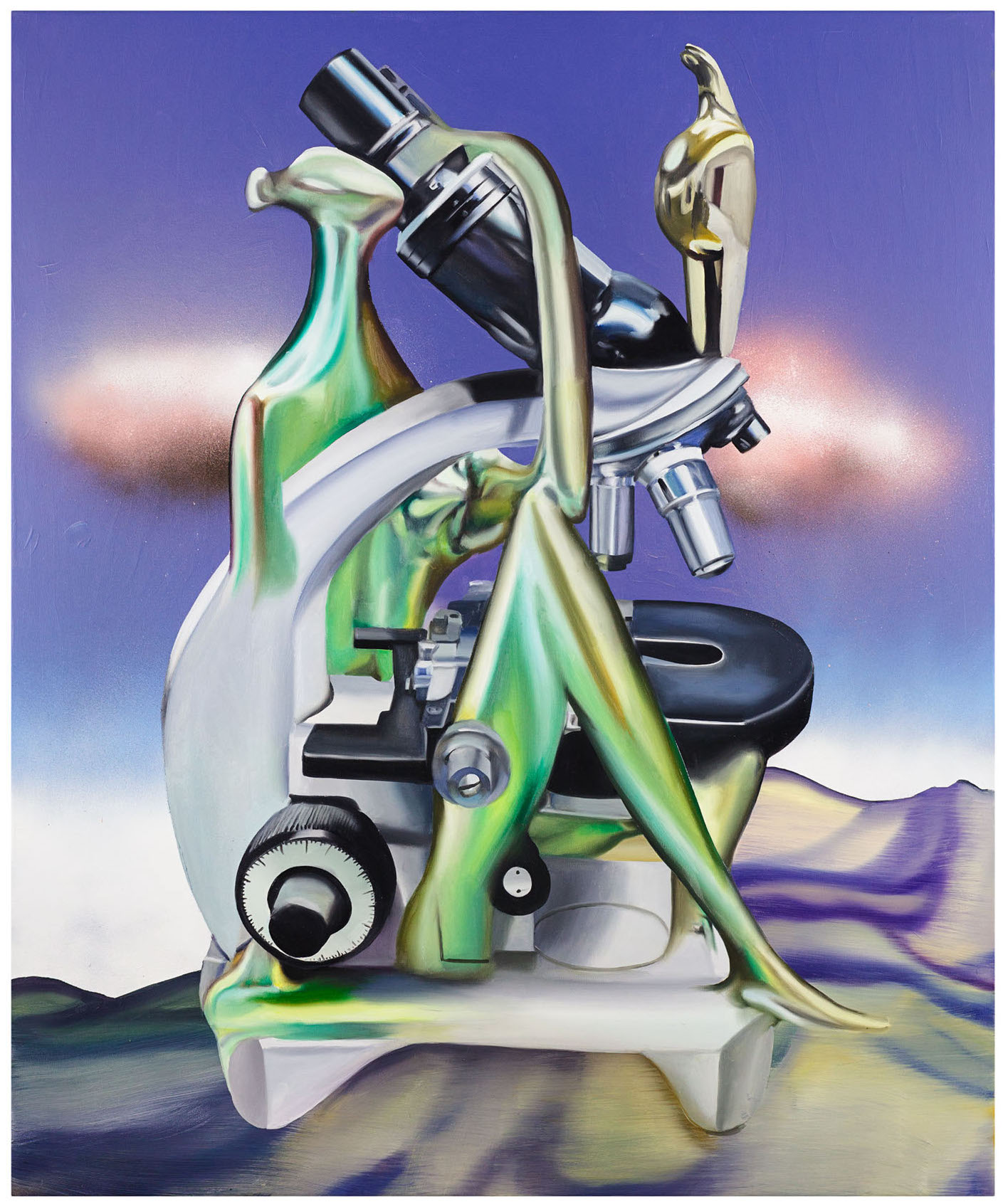

Today, of course, Instagrammers and TikTokers have joined the celebrity pantheon. And the wide-angle paparazzi lens that seeks to pierce the veneer of the slickly manufactured celebrity image is now joined by a high-res microscope operated by internet sleuths. In peeling back the Photoshop layers on social media posts, digitally networked audiences —much like their legacy media precursors — attempt to deconstruct the artifice of public figures in a bid to uncover who they “really” are.

Among the social media personalities under recent public scrutiny: an influencer-socialite accused of doctoring her Instagram posts, a TikTok comedian who flaunted a “partnership” with the controversial fast-fashion retailer Shein, and a beauty influencer who, in a “cringe-worthy” message strewn with typos, requested a free meal in exchange for a restaurant review. As this partial inventory suggests, the range of offenses for social media celebrities can be wide — FaceTuning a selfie is categorically distinct from an attempt to blackmail a restaurant — and the intensity of the audience’s reaction can be uneven too, ranging from spirited critiques to harassment, stalking, and even death threats. This past fall, YouTuber Em Sheldon explained to Members of British Parliament that influencers are frequent targets of abuse from “a dark space of the internet where people spend all day writing about us.”

The impossibility of “having it all” seems to motivate a lot of anti-fans’ critiques

This “dark space” includes not just the “toxic technocultures” that sully platforms like Reddit and Discord but also gossip forums and so-called “exposé” accounts like Influencers in the Wild, Kiwi Farms, Tattle Life, and GOMIblog (originally known as “Get Off My Internets”). These accounts scrutinize influencers’ every post and stream and collectively contribute opinions through caustic snark. While ardor unites them in spirit, the new possibilities of social media have enabled them to connect on a large scale.

Some influencers have publicly framed their denigrators as “trolls” or “internet bullies,” but media studies researchers including, Sarah McRae and Alice Marwick, have used the concept of “anti-fandom” to characterize such groups. Compared to the more casual “hater,” the anti-fan is distinguished by a deep knowledge of — and profound investment in — the objects of their disaffection. The targets of anti-fans’ ire run the gamut: politicians, actors, singers, athletes, and even animated animals have developed anti-fandoms.

As Jonathan Gray argued in 2005 about the pre-social-media site Television Without Pity, anti-fandom can produce “just as much activity, identification, meaning, and ‘effects’” as fandom can when it comes to “uniting and sustaining a community or subculture.” Much like their fan counterparts, anti-fans, he claimed, exhibit a preoccupation with “the moral and the emotional” elements of media properties in a way that sought to “to police the public and textual spheres.” In other words, anti-fans engage with broader social issues through close reading and discussion of media texts and personalities.

For example, the controversial antics of Apprentice cast member Omarosa Manigault Newman prompted the anti-fans at Television Without Pity to produce 200 pages of text and orchestrate a letter-writing campaign to discourage cosmetics brand Clairol from using her as a spokesperson. Gray explained that “a large number of [people] came together to decide that for a variety of reasons, they did not want this person in the public sphere, that she was poisonous to it, and that they should and could, therefore, ensure her exit.”

This response to Omarosa might seem familiar to anyone who follows influencer culture and has witnessed concerted efforts to “cancel” (to use a fraught term) those who have erred in the eyes of the not-so-adoring public. But not all missteps are created equal: In their communal monitoring of social media personalities, influencer anti-fan communities often focus their attention on feminine-coded content like fashion, beauty, lifestyle, and parenting. It’s perhaps not surprising, then, that the targets of these accounts are overwhelmingly women, as this list suggests.

While some influencers tend to cast anti-fans as “jealous haters” who resent the impeccable, presumably affluent women who grace their Instagram feeds, we contend that the animus directed at these content creators is far more complex. The patterned nature of the criticism directed at influencers — who have repeatedly been deemed “harmful,” “dangerous,” and “toxic” — suggests that these concerns extend beyond petty envy and into a rejection of the norms and values these women are seen to represent. Our forthcoming research focused on GOMIblog suggests that the persistent critiques lobbed at well-known YouTubers, TikTok creators, and Instagram influencers indicate a deeper frustration with the version of contemporary femininity that is encouraged — and often monetized — on social media.

Launched in 2008, GOMIblog bills itself as “the first blogger/influencer focused gossip website.” Since then, it has grown to include tens of thousands of registered members, with visitor counts upwards of 1.3 million monthly. Its members ostensibly take to the site to hold influencers and creators “accountable” by analyzing and reporting on their misdeeds. “Fakery” is a recurrent charge on GOMI. Whether characterizing Photoshopped images as “phony” or framing relationships with partners, friends, and even children as like-tallying “charades,” participants disparage influencers who defy the various, often gender-coded norms of social media authenticity.

As elusive as the “authenticity” ideal is, GOMI bloggers seemed to valorize “natural,” “unprocessed,” and “relatable” imagery while delineating “real” versus “performative” expressions. Accordingly, GOMI members call out excessive FaceTuning, artificially inflated metrics, and superficial brand devotion with gusto. Despite the fact that social media posts crafted for an audience are intrinsically performative, GOMI participants seem aggrieved that social media celebs profit — in some cases, quite handsomely — from cannily staged selfies and highlight reels. Such critiques belie a marked tension that Jefferson Pooley described in 2010, seemingly presaging the rise of Instagram, which launched the same year: Social media platforms are “calculated authenticity machine(s), where we are all asked to carefully curate our identities.” Indeed, as Richard Petersen argues, authenticity has long been “a moving target”; as such, part of the work for influencers — especially women — has been to convince audiences (and, conversely, advertisers) of their ability to successfully reconcile these tensions.

Our research found that the most harshly critiqued Instagram and YouTube personalities were disparaged for promoting ersatz depictions of “having it all”: self-fashioned careers, photogenic families, and youthful, “effortless” beauty — all packaged in one glossy, Instagrammable persona. To be sure, influencers are not the only archetypes of “having it all” furnished by digital culture: there are also well-heeled fashion bloggers, #GirlBosses peddling skin creams and yoga pants, and über-hip “mumpreneurs,” to name a few. The underlying message of contemporary entrepreneurial femininity is that all you need to achieve your dreams is to Own It, Believe It, say “Yes,” Wash Your Face, and Stop Apologizing — all while you #keepitreal.

At the heart of the criticisms was a sense that influencers are exploiting unachievable expectations

The “having it all” mythos, of course, has a long history in debates about feminism. This ideal emerged in the latter decades of the 20th century and took shape against the backdrop of 1980s exemplars of post-feminism: Melanie Griffith’s Working Girl, Murphy Brown, and Cosmopolitan’s iconic editor Helen Gurley Brown. The post-feminist promise of “having it all” insisted that women could have a high-powered career, motherhood, a fulfilling partnership (including a steamy sex life), financial stability, and time for friends and hobbies — all without a frisson of compromise. In an interview, Backlash author Susan Faludi recalled how the “having it all” ideal was “falsely held up as a feminist promise broken.” The canard was more recently revived in Anne Marie Slaughter’s viral 2012 Atlantic piece “Why Women Still Can’t Have It All,” which maintained that “the women who have managed to be both mothers and top professionals are superhuman, rich, or self-employed.”

Indeed, it is the impossibility of “having it all” that seems to motivate a lot of anti-fans’ critiques. Derisive comments about cosmetic surgery and cheesy #sponcon may appear to be surface-level frustration with the smoke and mirrors of social media; our analysis showed, however, that these objections were mostly targeted at influencers’ attempts to obscure the financial resources and mechanisms of social support needed to maintain their “flawless” lifestyles. At the heart of these criticisms was a sense that influencers are unethically exploiting expectations that are unachievable and unrealistic — at least, for most women.

A closer look at anti-fans’ repeated accusations of influencer fakery point to a deeper frustration about the lopsided provision of wealth and privilege in the contemporary economy. After all, “having it all” is within much closer reach when you can afford high-quality health care (including reproductive care), childcare, and housing. But this also points to the fact that influencers, rather than being seen as complicated and admittedly flawed individuals, are often held up as symbolic representations of larger structural issues, such as the persistent standards for womanly perfection that are inflected by race, class, aesthetics, (dis)ability, and more. Because they appear to be profiting quite considerably from the perpetuation of these ideals, influencers are treated as though they are single-handedly responsible for them.

This kind of extrapolation predates influencer culture. Gray discussed how the pushback against Omarosa stemmed in part from anti-fans’ claims that she set an example of workplace behavior that was “bad for women in general,” but particularly for women of color. Omarosa may have been the direct target of their frustration, but their overarching concerns were the sexist and racist strictures of the labor market.

We can see similar ideological undercurrents with social media anti-fans. Faced with skyrocketing living costs, a frayed social safety net, assaults on reproductive rights, and a lack of affordable childcare, women — in the U.S. and elsewhere — are exhausted, fed up, and justifiably furious. It bears repeating that for women of color, the situation is particularly dire; this CNBC report, for instance, details how “Black women have been hit ‘especially hard’ by pandemic job losses.”

In this context, anti-fan communities like GOMI — irreverent as they may first appear — become spaces to critique larger systems of privilege and inequality. Public figures like influencers — or in Omarosa’s case, reality TV stars — offer a distilled, big-picture target against which audiences can direct their anger with the status quo. Despite the connotations of fluff and feminized frivolity (as Erin Meyers and Alice Leppert detail here), gossip is not merely idle chatter. Nor has it ever been; it has long allowed women to, in Meyers’s words, “make sense of the wider world and their place within it.”

But while deeply rooted anger may animate the critiques waged against social media personalities, blaming individual women for the structural problems impeding women is neither effective nor productive. Whatever your opinion of Omarosa, there is an unfortunate irony to holding a single Black woman responsible for the employment prospects of all Black women amid the pernicious sexism and racism of corporate America.

Public figures like influencers offer a distilled, big-picture target

Furthermore, the psychological and social impacts on individual targets can be profound. Our research uncovered cruel attacks on influencers’ bodies, families, and parenting styles. Their mental health, moreover, was mocked in ways that raise the specter of gender-coded hysteria (e.g., “batsh*t crazy,” “delusional,” “lunatic”). Influencer hate is not confined to internet sites: in recent years, influencers have confronted “stalking,” “mommy shaming,” body shaming, and even death threats. The intensity of anti-fans’ critiques have prompted scholars to question where anti-fandom ends and toxicity begins.

What, then, should we make of influencer anti-fandom? Are anti-fans engaging in a form of necessary critique that prevents bad actors from profiting off of regressive gender norms? Or is it just age-old misogyny masquerading as banal commentary? The answer, like so much of digital culture, is more complicated than an either-or framing.

The kind of anti-fandom that we’ve discussed in this piece can be seen as a by-product of the fact that audiences — and women in particular — have few places to air their frustrations at the structural constraints they are living with. With progressive change on these fronts through voting or other sanctioned forms of political participation largely blocked or stymied through sclerotic political systems, it feels like “the familiar rules that governed the world” have unraveled and there is nowhere to turn, as Elamin Abdelmahmoud suggests in Buzzfeed. But instead of channeling energy and focus toward dismantling these higher-level problems, it ends up being directed laterally — a phenomenon that Emma A. Jane documents in her research on women-on-women violence in digital environments.

Holding individual women responsible for entrenched societal ills is a counterproductive way to address entrenched social inequalities. When women are pitted against each other as they so often are in the architecture of misogyny that casts individual women as archetypical stand-ins — the only real winner is the patriarchy. We acknowledge the lack of straightforward solutions to these issues; after all, they are fraught with complexity and wrought by contested understandings of identity, power, and privilege. But polarizing perspectives merely offer reappraisals of longstanding traps in gender and feminist politics.