They look like something you might buy from one of those minimalist, millennial jewelry brands, or an up-and-coming yoga and fitness studio. Understated, titanium rings; silicone bracelets with natural stone settings; teardrop-shaped pendants of composite wood on simple, stainless-steel chains. The rings are neutral and unisex — the bracelets and necklaces more conventionally feminine — yet all are relatively casual, intended for everyday wear. To the untrained eye, it is difficult to tell that they have anything to do with sleep.

Sleep wearables promote rest reconfigured as productivity

Beneath their nondescript exteriors, however, each of these pieces is studded with a range of sensors capable of detecting body temperature, heart rate, motion, and more. As they sit discreetly on the pulse points, each amasses mountains of this biological data, processing it via complex algorithms into simplified, wellness-oriented reports that are made accessible to the wearer via an app. These reports provide information on things like activity level and overall health — some even claim to be able to detect pre-symptomatic cases of Covid-19. Most importantly, they offer insight into that most mysterious and inaccessible of all bodily functions: sleep. Do you want to clarify the contours of your nebulous eight hours and see just how much of it was spent in deep sleep, light sleep, and REM sleep? Just ask your bracelet. Do you want personalized recommendations about the best time to close your eyes to achieve your most optimal amount of rest? Just ask your ring. Light, compact, and virtually indistinguishable from their purely ornamental counterparts, today’s sleep-tracking jewelry pieces are the culmination of years of advancements in sensor design and computing power. And yet, they are but the latest in a long line of rest-related accessories and accoutrements: objects whose shifting material configurations express — and produce — equally diverse ideologies of sleep itself.

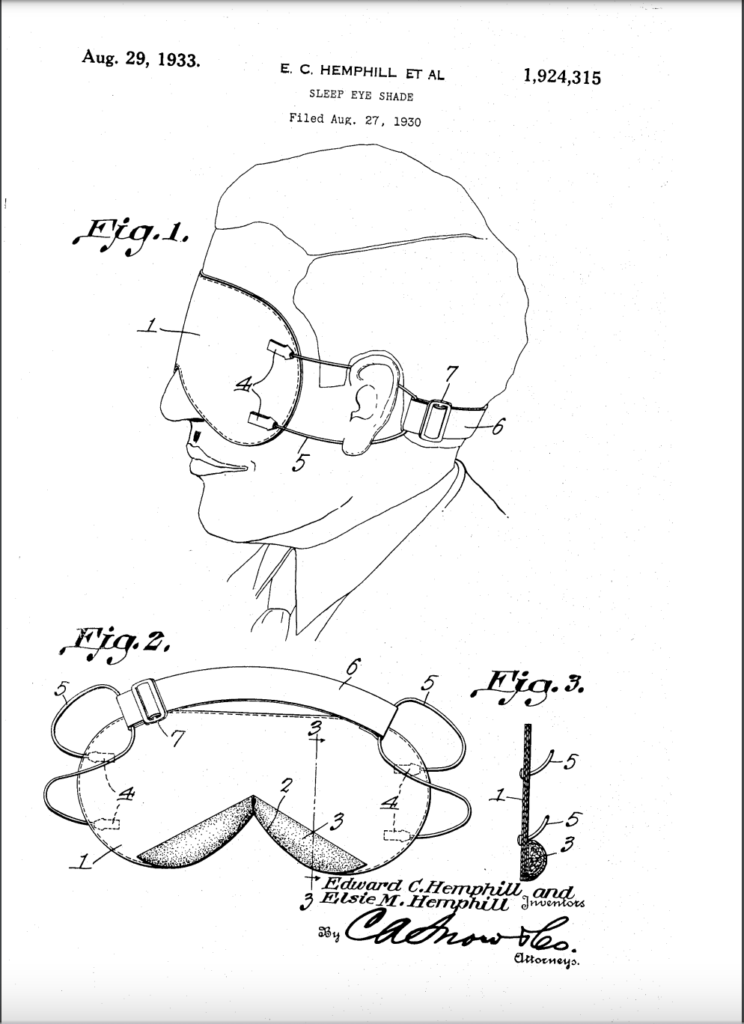

In 1930, Edward and Elsie Hemphill of San Francisco, California filed a patent for a product called the “sleep eye shade”: an invention designed to protect its sleeping wearer from disruption by light. Consisting of a piece of soft, opaque fabric that fastened snugly over the eyes, the “sleep eye shade,” or sleeping mask, was one way of promoting rest amongst 20th-century city dwellers reckoning with a sudden rise in ambient electric lighting. Decades later, a host of artists and fashion designers would offer their own variations on this theme, producing an array of voluminous, textile-based items that aimed to bring the bed to the body. These include the down-filled dresses with built-in pillows designed by Italian postmodernist Cinzia Ruggeri (re-interpreted in 2005 by Viktor and Rolf), Norma Kamali’s sleeping bag jackets, and Martin Margiela’s iconic duvet coats. More playful than practical, these garments experimented with earlier, more pragmatic down-based construction techniques developed by workwear designer Eddie Bauer for his 1936 “Skyliner” jacket, the first puffer jacket to be patented in America. Intervening at the surface of the body, they approach sleep as an external phenomenon: one that can be encouraged through the regulation of environmental variables such as warmth and softness.

In 1959, Hugh Hefner’s famous circular bed was installed in the Playboy mansion. Designed by architect R. Donald Jaye, the bed not only vibrated and rotated, but also came equipped with a variety of state-of-the-art media and communications technologies, including a telephone, an intercom, and a television. The bed of architect Richard Neutra, located at his VDL research house in Silver Lake, Los Angeles, boasted a similar array of hi-tech devices, including two phones, three intercoms, and a gramophone that could be operated via controls embedded in the headboard. A few years later, in 1969, Italian architect and designer Joe Colombo would unveil his own take on the tech-bed: a piece of furniture he called the “Cabriolet Bed.” Part of his futuristic “Living Machines” series, the bed merged a sleeping surface with a cigarette lighter, a radio, a television, and an electric fan.

These mid-century tech beds display a curious ambivalence — if not outright hostility — towards the biological function of sleep itself. Re-imagining rest as something to be combined with other, more industrious activities — reading, writing, corresponding with friends and colleagues — they appear far more concerned with staving it off than they are with encouraging it. As architectural theorist Beatriz Colomina has pointed out, they contain a premonitory glimpse of the state of constant connectivity that would be facilitated by the rise of the smartphone and other personal computing devices. They also represent an early, design-based manifestation of what Jonathan Crary has diagnosed as the widespread, institutionalized insomnia of our late-capitalist present.

For Crary, contemporary life increasingly takes place in the confines of the “24/7 universe,” defined by its emphasis on constant productivity and its utter disregard for the natural rhythms of human life. Demanding from its subjects the same capacity for continuous, uninterrupted operation that is exhibited (or at least simulated) by inert systems like global markets and wireless networks, this universe has no room for sleep and the “incalculable losses it causes in production time, circulation, and consumption.” An act (or, more accurately, a mode of inaction) that brings both labor and the movements of accumulation — shopping, scrolling, downloading — to a forcible pause, sleep is anathema to the 24/7 universe. Correspondingly, it is also the target of increasingly aggressive efforts to lessen its frequency, inevitability, and overall hold over human life. Though caffeine has been a part of human life for centuries, the energy drinks of the past three decades encourage its consumption in volumes that far exceed those that naturally occur in coffee and tea, and that frequently verge on the dangerous. Twenty-first century amphetamines like Modafinil take this chemical stimulation to a new level, promising users the ability to stay awake for up to 48 hours. While both of these examples already make the hi-tech beds of Jaye, Neutra, and Colombo seem positively relaxing, recent experiments conducted by the U.S. Department of Defense best capture the ultimate goal of the 24/7 universe with regards to human rest. Their focus? The biological mechanisms that enable the white-crowned sparrow to remain awake for seven consecutive days.

Rigid rather than soft, sleek rather than pillowy: the sleep wearables of today are the material opposite of the “analogue” wearables of the past. Eschewing more comfort-based approaches, they locate the key to a good rest inside the individual body itself, treating sleep as an internal, purely physiological phenomenon. Examples include Sleepon’s Go2Sleep ring (which recently added blood-oxygen monitoring to its roster of metrics), as well as a ring by Australian-based company Thim, which incorporates aspects of sleep training as well as sleep tracking. For those interested in adorning other parts of their body, bracelets and necklaces from Bellabeat also offer significant sleep-related capabilities, along with other, more generalized wellness functions. By far the most well-known sleep wearable is the eponymous ring made by Finnish company Oura, which as of March 2022 had sold over one million units.

These mid-century tech beds display an ambivalence or outright hostility toward sleep itself

Although personal biometric tracking devices from Fitbit, Nike, and Jawbone had been available for at least a decade when the Oura ring was released, Oura’s was the first to claim sleep — rather than activity — as its raison d’être. First made available in 2015 under the slogan “Improve Sleep. Perform better,” it represented a significant mutation in the tech wearable insofar as it targeted the sleeping body, rather than the waking one. While earlier, activity-focused wearables could only provide users with rudimentary estimates of their total sleep time (if they incorporated any sleep functionality at all) the Oura ring offered calculations of the precise time their wearer had spent in particular sleep stages. It also established a feedback loop between sleep and performance, mobilizing activity data in service of sleep (through features called “actionable insights”) and quantifying, as a “readiness score,” the effects of sleep on waking activity. For example: If, according to the Oura ring’s evaluation, you had a night of poor sleep, you would be likely to receive a poor “readiness score” the following day. This score would likely be accompanied by words of encouragement to “train carefully” or “go easy” until your rest levels were restored. On the other hand, if you had accrued what the ring judged to be a good night’s rest, you would be likely to receive the opposite advice: that which prompted you to “go strong.” Although it now emphasizes both sleep-tracking and more general wellness-related functions, sleep tracking remains the Oura ring’s best-known role. As a 2021 New York Times review of the device put it: “The Oura Ring Is a $300 Sleep Tracker That Provides Tons of Data.”

In the midst of our sleepless present, do sleep wearables not represent a glimmer of hope? Does their pursuit of the perfect rest not signal a valuable moment of respite in the ongoing war against respite itself? On the surface — and especially when positioned next to some of the more categorically anti-sleep technologies described above — the answer appears to be “yes.” Instead of attempting to outrun it through various chemical, pharmaceutical, or other yet-to-be-imagined means, sleep wearables underscore, in various quantified ways, the negative effects that sleep deprivation can have on waking life. Though detrimental for some, these quantifications — a low sleep score, a notification that encourages one to “take it easy” — are for others a necessary encouragement to slow down, stop moving, and set aside some time for rest.

They also accomplish something else. By linking sleep with activity, the Oura ring promises significant improvements to both realms. As the company’s original Kickstarter put it: “By understanding how well you slept and recharged, [the Oura ring] can determine your readiness to perform and help you adjust the intensity and duration of your day’s activities. It can also uncover actionable insights for changes to your daily activities that can help you sleep better.” While this project is one of optimization — one that seeks to uncover an “ideal” sleep perfectly balanced to the needs of a particular individual — it is also one that effects a rhetorical transformation of sleep, from passive event to active process. Though the Oura app provides users with a “raw” sleep score, users are equally, if not more likely to consult their “readiness score,” which presents sleep not as a valuable or necessary experience in itself, but as a mere substrate of performance: an invisible background factor in a user’s ability to “take on the day.” The ring’s “actionable insights” — “action” being the key word — have a similar effect, embellishing the fundamental passivity of sleep under a layer of activities and practices so that it too, in the end, resembles something that can be consciously endeavored. Although sleep wearables seem to be promoting rest, what they actually promote is rest reconfigured as productivity.

If you had what the Oura ring judged to be a good night’s rest, you would be prompted to “go strong”

A basic premise of the sleep wearable — whether it takes the form of a ring, a bracelet, a necklace, or a brooch — is that it lasts continuously through the night, something reflected in the long battery life of even the most inexpensive devices. A properly charged wearable is thus always “awake,” functioning as a kind of surrogate, low-level awareness that functions even while the user is forced to abdicate their own. More significantly, these devices do not just simply stay awake: they record. No longer content to let sleep slip away like a fog with the light of morning, sleep wearables disturb the fundamental psychic balance implied by Freud’s “mystic writing pad” which, though it preserves every trace, stores most of them in a place inaccessible to the conscious mind. Unlike this “mystic writing pad,” the digital inscriptions of the sleep wearable are always at hand: accessible with the push of a button.

A properly-charged wearable is — in other words — always awake, acting as a sort of surrogate, low-level consciousness that keeps running and recording even while you temporarily abdicate your own. Not only do they make sleep optimizable, they gesture strangely toward transforming sleep from an unconscious act into a conscious one. Underneath their professed “sleep-positivity,” sleep wearables are insomniac technologies.

It could be argued that the shifts detailed above have little to no effect on the biological reality of sleep itself. Though they may re-sculpt it in the figurative domain, that could never be enough to change sleep’s physical inevitability, nor its constitutive qualities of passivity and unproductivity. And yet, it is worth asking if their effect on our cultural imaginary around rest could not have the additional, more insidious effect of paving the way for future incursions into this already threatened domain. As we become accustomed to the increasing convergence of sleep and action — and increasingly unaccustomed to experiencing sleep outside frameworks of production and activity — who knows what further reductions, adulterations, and debasements to our repose we might accept? There is also the simple, non-rhetorical fact that, as they wrest strings of manipulable data from our most base-level physiological functions, sleep wearables quite literally transform rest into an extractive resource. Under their endless watch, sleeping bodies become productive ones, a process that mounts a disturbing challenge to Crary’s optimistic assertion that “in spite of all the scientific research…[sleep] frustrates and confounds any strategies to exploit or reshape it.”

In a 1961 essay entitled “From Gemstones to Jewelry,” Roland Barthes makes the polemical assertion that modern jewelry has lost its “infernal aspect.” This is, he argues, because it no longer makes substantial use of gemstones — the ultimate relic of the underworld — but rather understated, earthly materials such as glass, wood, and inexpensive metal. For Barthes, today’s jewelry is just another object: something banal, unremarkable, and definitively un-supernatural. “Having originated in the ancestral world of the damned,” he writes, “the piece of jewelry has in one word become secularized.” With their neutral palettes, composite wood, and inoffensively minimalist design, the sleep wearables of the past decade initially seem to confirm this thesis. And yet: There is something damned, or at least paranormal, about rings that transubstantiate the vapors of sleep into visible, instrumental data. Bracelets whose invisible eyes are always open, even while yours are closed.