1. The canonical, stereotypical memory object is Proust’s madeleine, a small, buttery, shell-shaped cake that when dipped in hot tea becomes the catalyst for the densely wrought memories that make up Proust’s seven-novel cycle. But modern life, each individual life, is peppered with evocative madeleines, some uniquely of our time, some evergreen. The scent of garlic and butter wafting out of a kitchen just before dinner. A particular song coming on over the radio. The embodied memory of turning your car into the driveway of your childhood home. The serendipitous rediscovering of a yearbook or a childhood diary. These objects and experiences induce reminiscence, and we re-member, literally piecing together our memories as they are called to mind, and through that process of re-membering, we also piece together ourselves, as Proust does.

2. Psychologist Dan McAdams, a professor at Northwestern University, holds that central to a happy life is the creation and maintenance of life narratives, dynamically evolving situated performances that integrate lives in time, providing what Adams describes as “an understandable frame for disparate ideas, character, happenings, and other events that were previously set apart.” These stories are subject to constant additive revision, as through living we continually add more material and revise the material available to us, rethinking and rewriting memories as we age. The process of remembering memories rewrites them, revises them, and this ability to re-envision ourselves is a central part of the creation of seemingly stable life narratives that allow for growth and change. If we were to lose, somehow, the ability to both serendipitously and intentionally encounter and creatively engage with our memories, perhaps we would then also lose that re-visionary ability, leaving us narratively stranded amidst our unchanging, unconnected memories.

The digital homunculus of memory is gorged on attention, and on recognizable personal milestones

3. The social web has given us, in its infinite, generative wisdom, a suite of products and services to programmatically induce reminiscence. Apps like Timehop, which presents time-traveled posts from across your social media profiles, or Facebook’s “On This Day” Memories, are attempts to automate and algorithmically define reminiscence, turning the act of remembering into a salable, scalable, consumable, trackable product suite. As the work of memory keeping is offshored, Instagram by Instagram, to social media companies and cloud storage, we are giving up the work of remembering ourselves for the convenience of being reminded.

4. There are three different “memory” systems that I’m talking about here: predictive text, those systems concealed within your phone’s keyboard that prod you to call your dad “pookie” because that’s what you call your girlfriend; reminiscence databases like Facebook Memories or Timehop; and data doppelgangers constructed for ad targeting, the ones responsible for those socks that follow you around the internet even after you’ve bought six pairs. Each interacts differently with the data it collects, representing it to guide or nudge you according to different models. But the core of these models, their fundamental shared strategy, might be reduced to: “Those whose past is legible will be exhorted to repeat it.”

5. Text prediction and autocorrect on your smartphone operate on two parallel models of algorithmic prediction: the general, which for each language set scans a pre-selected corpus of general interest and more esoteric websites that provide models for grammar, common sentence construction, vocabulary and slang; and the personal, from a corpus of individually generated content data, like text messages, emails, tweets, search requests, etc. So predictive text systems push the user in two directions simultaneously: be more generic — that is, adhere better to the corpus of generic source data — and be more like you have been in the past. Use the same words, the same syntax, the same mannerisms that you have used in the past. Be more like the cliché of you.

6. Similarly, the ad-targeting data doppelganger is more like a data echo, but even that doesn’t quite cover it. Perhaps a better phrase would be data homunculus, the homunculus being the exaggerated, misshapen model of a human being intended to show the distribution of nerve endings in the human body. The hands, lips, tongue, and head of the somatosensory homunculus are grotesquely enlarged, reflecting those aspects of the body that the model is most concerned with. Similarly, the data homunculus can only reflect those aspects of yourself that are legible to the systems that seek to model you. The “you” reflected back is warped by the legibility of your behavior, and the interests and preconceptions of the model builders. Predictive text on your phone cannot (yet) take into account the differences between your spoken speech patterns and your typing patterns; ad targeting based on searches and Amazon browsing is a model based fundamentally on what you don’t have.

7. Recommendations can set paths for individuals, particularly when they offer shortcuts. Communications shortcuts in particular have changed the way humans talk to each other, restricting vocabularies, changing what is expressed or sometimes the fundamental meanings of utterances. Jonathan Sterne has written on telegraph code books, popularized as an analog mode of compressing complex communications into short strings of letters that could be sent over a wire cheaply. Because these code books were distributed pre-composed, if what you wanted to say wasn’t already available, you might have just gone with the next closest equivalent instead of spending the money to send a longer, more precise message. We’re already aware of how “lol” and “IRL” have worked their way into everyday spoken speech, but there is also the delightful example of “that’s so book,” a short-lived slang expression based on a T9 autocorrect suggestion for “that’s so cool.” Suggested speech becomes speech itself.

8. Algorithms don’t just act upon people. Scholar Tania Butcher has noted that people also act upon and toward algorithms, orienting themselves and their communications according to how they determine various algorithms in their lives to function. In a social environment that has in many ways conflated social importance with algorithmic recognizability, it is necessary, for example, to ensure that Facebook can recognize your engagement announcement for what it is, if you want to make sure all your friends from high school see it. Digital reminiscence systems require the creation of digital memory objects, and prod us algorithmically to create specific kinds of digital memory objects, those that are algorithmically recognizable and categorizable, as part of their functionality.

Social media posts are designed to be in and of the moment, and, when presented back as “memories,” carry all the authority of eyewitness testimony

9. McAdam’s life narrative is made up not so much of memories as it is by the active, personal, and performative act of remembering. The inputs into Facebook or Timehop are not bits of narrative. A Facebook Memory cannot be a narrative fragment because it is static. But to state the obvious, it is also not a memory: It is a socially contextualized performative expression. Facebook’s re-presentation of these “memories” strips them of context, recategorizing them as “events” or “moments.” They are both separate from their own context in time and, as memory objects, unavailable for the remembering and rewriting that would be necessary to interpolate them into a coherent personal narrative.

10. The databases exist outside of time and outside of narrative. Social media posts are designed to be in and of the moment, focused on a completionist recency in a way that breaks even conventional models of the present. Presentness becomes redefined as relevant-right-now, based on a FOMO-informed anxiety about knowing-what-other-people-like-you-know. Social media are present-tensed broadcast platforms, intent on capturing ostensibly of-the-moment situated expressions, which, when presented back as “memories,” carry all the authority of eyewitness testimony and all of its problems as well.

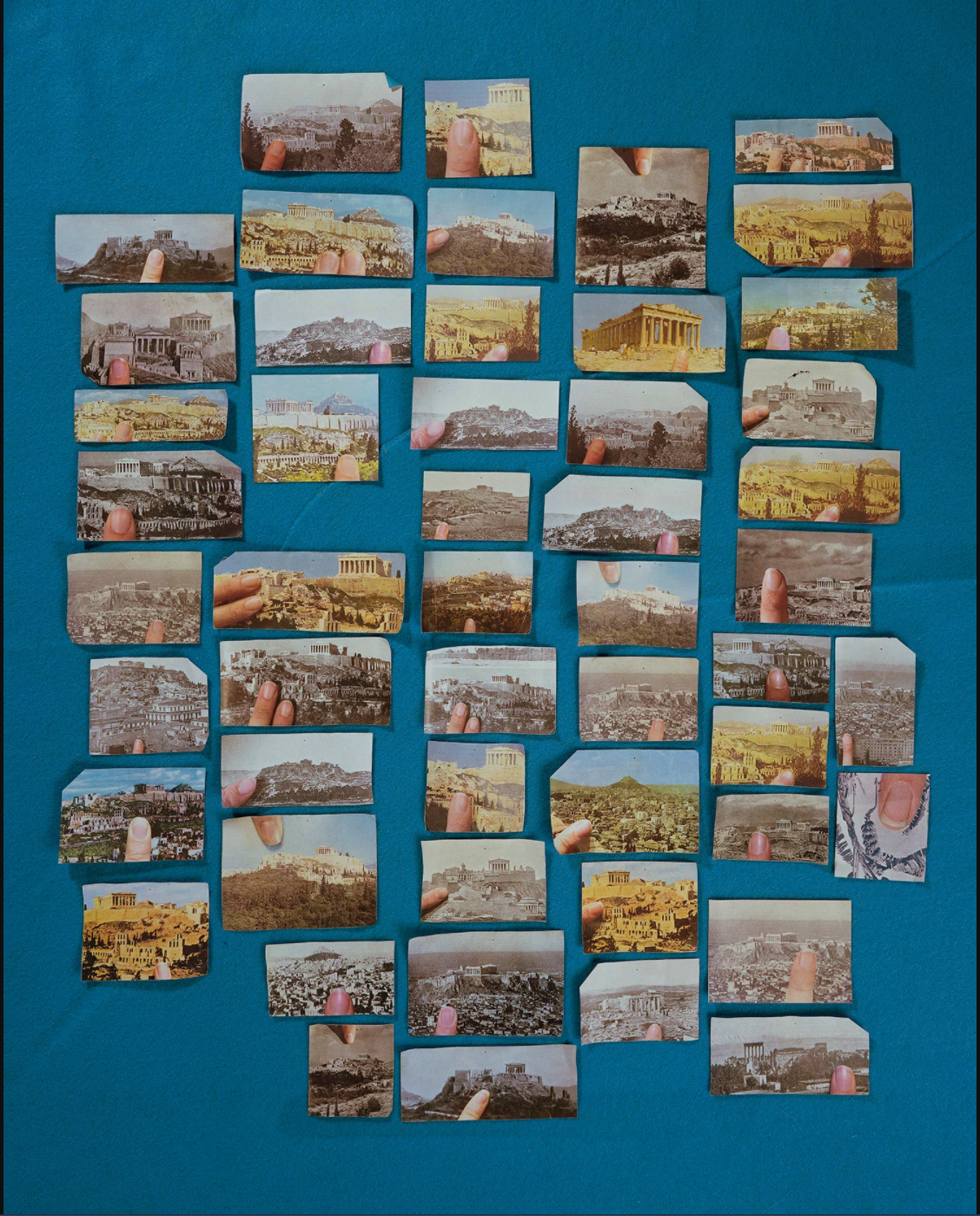

11. Memories change with the remembering, and evocative objects change as we age together. Physical objects, like yearbooks, photographs, cars, houses, trees, gravestones, exist in a place and are re-encountered, or are discovered to be conspicuously absent a la Grosse Point Blank, at specific moments: perhaps going home for the holidays, or moving to a new apartment, or clearing out a relative’s home after a death; transitional, evocative moments. These physical evocations age, and their value and veracity as objects of testimony ages with them and us. They date, they fade, they display their distance from the events they are connected to and their distance from us. Digital memory objects, on the other hand, although they might abruptly obsolesce, do not age in the same way. They remain flatly, shinily omni-accessible, represented to us cleanly both in the everlasting ret-conned context of their creation and consumption. The user interface of Facebook doesn’t time-machine itself to the design it had when you composed whatever memory it is showing you from 10 years ago. In the visual context presented, you could have written it yesterday.

12. In these databases, digital memory objects exist coincidentally, but not inter-influentially, allowing for the existence of thousands of moments of presentness or presence. Jess Zimmerman, in her story “A Life in Google Maps,” writes of the emotional vertigo induced by this all-of-time-all-at-once: “Inside Google Maps, we still live together.” Zimmerman notes that inside the world held statically navigable in Google Maps, multiple moments in time exist simultaneously. It’s 2012 at her old house, it’s 2008 at her ex-husband’s lab, and it’s 2014 at her office. “Inside Google Maps,” she writes, “I live with you, and I live without you.”

It’s as if the wellness obsession with “being in the present moment” that has creeped into Silicon Valley over the past few years has resulted in a familiar technological hoarders tendency: if living in one present moment is good, living in endlessly arrested presents must be even better. A continual living in the present means there is no space for reflection, for coherence-building. There is just the continual, lepidoptery-like collection of “moments.” Memories turned into mere mementos. Remembering turns into reminding.

The wellness obsession of Silicon Valley has resulted in a familiar technological hoarders tendency: if living in one present moment is good, living in endlessly arrested presents must be even better

13. The inability to control remembering, to the point where it interferes with daily life, causing emotional distress and prompting the creation of strategies to manage intrusive memories, is a core symptom of several psychiatric disorders, most notably Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. Oliver Sacks described a patient who suffered from unpredictable, overwhelming fits of reminiscence as suffering from “incontinent nostalgia.”

When I asked my friends for examples of times Facebook Memories had brought up upsetting memories unexpectedly, I was overwhelmed by responses: people who had been reminded of dead pets, dead parents, dead friends, abusive exes, or times when they were sick or sad. One friend spent an inordinate period of time tensed in anticipation of the memories he knew were coming but he didn’t know when.

14. The Memories Facebook displays to you, cheerily, at the top of your News Feed, appear to be a combination of fixed events it algorithmically recognizes as significant: engagements, weddings, birthdays, graduations, celebrations, and posts that were especially popular. My acquaintance with the dead dog was exhorted to remember the day he put his pet down, probably because the post got a good deal of traffic from friends offering their condolences. The algorithm conflates attention with positivity: surely if so many people paid attention to this event, engaged with it, clicked on it, this is a thing you would like to be reminded of. The digital homunculus of memory is gorged on attention, and on recognizable personal milestones.

15. Facebook now gives you the option to blackout dates or individuals from appearing in your Memories. But as we, and others around us, export more and more of the infrastructural work of personal memory storage and retrieval to these technological superstructures — as evocative objects like photo albums, mix tapes, and handwritten letters are replaced by digital objects — blocking out stretches of time or exes or frenemies will increasingly leave us with two options: riddling our personal structures of remembrance with amnesia, as the evocative paths to memories are obliterated; or leaving ourselves open to continual assault by programmatic nostalgia.

16. In the film Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, we saw a version of the personal amnesia future taken to a logical extreme. If we delete these digital memory objects, we no longer run the risk of being assaulted by them, but we also destroy the potential to helpfully re-encounter them, perhaps serendipitously, when the sting of the original event has faded. Digital memory objects and digital reminiscence systems have left us in a catch–22: They are poor but convenient substitutes for the physical objects and mementos we have previously relied on as containers of memory. If we destroy the evocative electronic madeleine, we are left more and more floating in a self-replenishing sea of presentness and recency.

But if we don’t, if we leave the madeleine in safe stasis in memory storage, we may be accepting a different type of tyranny, of memories that refuse to be altered, of constant confrontation with all of you at once, everything algorithmically legible you’ve ever done, existing simultaneously, clamoring for influence and attention.