In Labylogue (2000), Maurice Benayoun, Jean-Pierre Balpe and Jean-Baptiste Barriére’s virtual art project, cyberspace is presented as a blue labyrinth of rooms. Participants in three different French-speaking cities — Brussels, Lyon and Dakar — connected by the internet were invited to navigate these rooms using a joystick and a microphone, unable to see each other but able to start conversation. Inspired by Jorge Luis Borges’ short story “The Library of Babel,” an infinitely vast library of connected chambers holding every possible combination of letters, the walls of Labylogue’s interlocking rooms are scattered with seemingly endless and largely indecipherable, pixelated sentences: The participants’ conversations, interpreted and distorted by speech recognition software, are mapped over the walls in translucent layers.

These interlocking hexagonal chambers are the metaphorical chambers of the internet: vast, expansive and infinite. Just as the participants mimic walkers navigating a physical maze, they also mimic the wanderer drifting through pages of information. Labylogue starts with a “digital dualist” approach, positing the digital and the physical as separate spaces — but combines them to examine the points at which the two converge to speak to each other. It’s a step from there to imagine digital and physical space as two overlapping layers of the same topography. What plagues social media plagues our cities; occupying space online holds similar significance on the streets. “Cyberspace,” then, is not separate or distinct from the “real” world, but another dimension of it; one dimension illuminates the structures of the other.

Dérive focuses on a psychic sensitivity to our environments. It encourages the occupation of space… which can be as restrictive as the laws that govern it

The walkers in Labylogue do not move forward, but in curves or angles, spiraling inward to an enigmatic center, following an instinctive code of direction. This instinctive drifting reinterprets what the avant-garde Situationist International termed dérive in the 1950s. It was developed from the principles of Guy Debord’s psychogeography, which accounted for the emotional effects of an urban environment on its walkers, claiming that a city was mapped in psychic zones. Why does a walker feel a shift in atmosphere at a street corner when the physical geography has not altered? Why does one drift, instinctively, to the left hand side of the street when both pavements are clear? What codes these spaces with meaning? Dérive, then, is defined as unstructured drifting through urban environments to attune oneself to a city and its shifting ambiance. The “walkers” in Labylogue practice this dérive digitally, guided by instinctual reactions to certain rooms or passageways, weaving a unique path as one would drift impulsively through city streets.

Dérive focuses on a psychic sensitivity to our environments, and illuminates their fractures. It encourages the occupation of space; it moves us to follow and read the city’s hidden rhythms and practices. When public space — on the street or through a screen — is structured to keep us out, dérive moves beyond leisurely to become political.

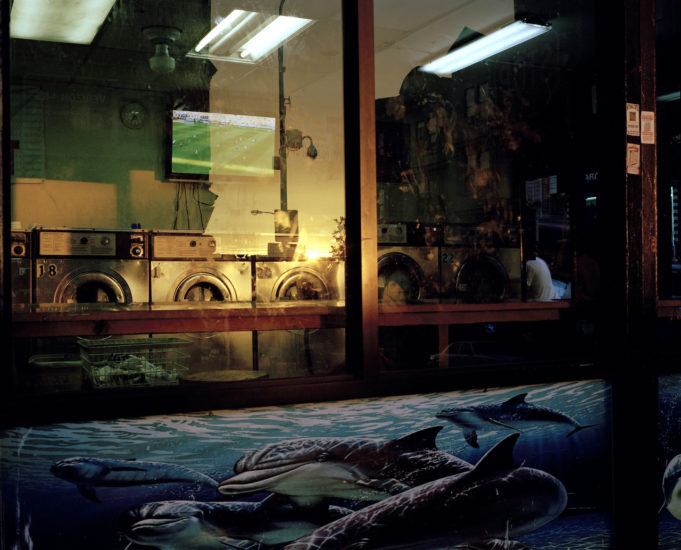

In the sixth issue of the Situationist International magazine, Belgian writer Raoul Vaneigem wrote: “All space is occupied by the enemy. We are living under a permanent curfew. Not just the cops — the geometry.” Space, he suggests, is restrictive, just like the laws that govern it. The Situationists were interested in how we inhabit space, and the ways we are discouraged from doing so. Their practices help decode the invisible boundaries of our public spaces today. When one group of people stages a protest in the streets, it is not threatening; when another group does the same, it is aggression, violence. A poorly lit street or alleyway takes on a radically different atmosphere for the solitary female walker; a street filled with police officers takes on a different, more violent meaning to people of color. Two years ago, a man shared a photograph on Twitter of spikes situated outside a block of London flats to deter homeless sleepers, one example of countless metal studs on benches and in doorways across cities globally. The geometry of public space is structured to close in, to shut out, to reconfigure access; it shifts shape according to its walker.

The internet is mapped by the same restrictive psychic zones: a culture that harasses its women on the streets also harasses them online; a culture that devalues black lives also threatens these lives online; the dualist perception unravels to reveal both spaces as separate layers of the same geography. The authorities who fail to act on this violence — or who instigate it — take a similarly aggressive or laissez-faire approach to abuse on the internet. A study this year found that almost half of all women interviewed experience online harassment, and one in four lesbian, bisexual, or transgender women experience homophobic and transphobic abuse. Police fail to adequately address numerous racist Facebook threats, while Facebook itself takes no action; women are shut out from online gaming communities with sexual harassment; Instagram censors photographs of menstruation and pubic hair. What does it mean to occupy these spaces, then, in spite of these restrictions?

Invisible boundaries are illuminated with the marginalized walker’s presence; to practice dérive in spite of these obstacles is to do the work of removing them

Lauren Elkin explores this in Flâneuse: Women Walk the City, which re-imagines Charles Baudelaire’s flâneur figure, the urban wanderer of 19th-century Paris. Baudelaire’s flâneur took part in the dérive the Situationists advocated, but for him it was largely a leisurely activity, enabled by a dearth of responsibility and the privilege of safe access to urban space. “There was always a flâneuse passing Baudelaire in the street,” Elkin writes. French for “stroller,” the flâneur was likened to “a kaleidoscope gifted with consciousness, responding to each one of its movements and reproducing the multiplicity of life.” He entered into the city crowd “as though it were an immense reservoir of electrical energy.” (Baudelaire’s descriptions are threaded with movement and electricity — a language that merges the digital with the physical, and helps us to imagine how the flâneur moves today.) However, “space is not neutral,” Elkin writes. “Space is a feminist issue.”

“Cities are made up of invisible boundaries,” she continues, “intangible custom gates that demarcate who goes where: certain neighborhoods, bars and restaurants, parks, all manner of apparently public spaces are reserved for different kinds of people.” The Situationists sought to understand these invisible boundaries. They argued that to understand space, one must occupy it — become attuned to its methods of intimidation and restraint. “To dérive was to notice the way in which certain areas, streets, or buildings resonate with states of mind, inclinations, and desires,” writes Sadie Plant, and these aspects of dérive take on a distinctly political dimension in cities permeated by police presence, where surveillance is increased and “public” space is reconfigured to restrict access. Elkin’s flâneuse is a necessarily political figure. Invisible boundaries are illuminated with the marginalized walker’s presence; to practice dérive in spite of these obstacles is to do the work of removing them.

If dérive is drifting to attune oneself to the landscape of the city, then online it is the practice of drifting to attune oneself to the global landscape, becoming sensitive to undercurrents of culture, the subtle tremors of social change. As Baudelaire’s flâneur stands in the crowd to observe, the modern flâneur/se refreshes their feed; their world expands beyond geographical borders, and the flâneur/se gains a more expansive global consciousness. We are no longer restricted to our own private pockets of space.

The consumption of social media is a far from idle activity. Online dérive is developing a sensitivity to spatial surroundings at grassroots level: to collective movements as they happen; to social media movements — #BlackLivesMatter, #YesAllWomen, #KeepCorbyn — that begin as hashtags across the globe and then take to the streets. Being online is being privy to the dissemination of information unavailable elsewhere; it is observing the conception of change, and participating in the gradual momentum of political movements. Drifting online encourages us to pay attention to voices we do not encounter drifting in the streets. It is an intimate stroll through alternate subjectivities. While Baudelaire’s flâneur is limited to his street, the modern flâneur/se is equipped with two simultaneous public spaces, each illuminating fractures in the other.

The modern flâneuse drifts across borders to merge them; as we decode one space by moving through it, we decode the other

Just as physical cities influence the political and cultural structures of the internet, so do those structures influence our cities. #BlackLivesMatter was started in 2013 on Facebook by Alicia Garza, Opal Tometi, and Patrisse Cullors; a year later, it moved from the screen to the streets of Ferguson, Missouri after 18-year-old Michael Brown was murdered by police officer Darren Wilson. Since its conception, 23 chapters have formed across America and Canada, spreading to London, France, and Africa; in just one year, the movement organized over 950 demonstrations. A series of #BlackLivesMatter protests in London (organized via Facebook) earlier this month in response to continuing horrific police brutality in the U.S. shut down traffic and roads in Brixton, Westminster, and Oxford Circus. Thousands of protesters occupied the streets and refused to leave; the city ground to a halt.

Just as these protests fill the streets with banners and plaques reading “Life is not a white privilege,” “No Justice, No Peace,” and “Hands Up, Don’t Shoot,” #BlackLivesMatter simultaneously floods Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook feeds with images and reports of protest, demanding to be thought about, infiltrating new levels of public consciousness. It disrupts the privileged, detached mode of Baudelaire’s flâneur, who can ordinarily drift through space without acknowledgement of the city’s invisible boundaries. Social media illuminates these boundaries, and works to make the reality of other people’s lives impossible to ignore. Social media is committed to the most recent news, but it also refuses to let history erase itself. It holds those responsible accountable. It preserves wrongdoing.

The hashtag #BlackLivesMatter is scrawled on the side of buildings in neon graffiti across the world; “cyberspace” and the physical are revealed to be woven together. What begins online has the power to shut down transport, to delay services, to occupy public sites with public issues. It facilitates global movement. Fitting that these hashtags are shaped like grids, layered over the city in interlocking lines: digital and physical space merge to create gridlock.

Situationist practice offers a new perception of our contemporary cities and online spaces: not as separate or opposed, but as two overlapping dimensions of public space. The Situationist practices of dérive encourage us to attune ourselves to the hidden implications of these spaces, to decode the architecture of cities, to challenge the invisible borders as they manifest online.

The “walkers” in Labylogue blur the distinctions once made between digital and physical, just as the modern flâneur/se drifts across borders to merge them, enacting an occupation of both landscapes simultaneously; as we decode one space by moving through it, we decode the other. Digital dérive, then, does not replace physical dérive, but facilitates and complements it, gathers its momentum with velocity. It does not replace walking through the city, but offers a new perception of topography: If we can fill the internet with our voices, why shouldn’t we fill the streets?