When I walk outside at night in Chicago, I look for lit-up interiors. I don’t care about seeing the people inside, but I do want to see how they live. Do they have a fireplace? Is it real? Are there pictures hung above it like mine? I look so long and hard into people’s private spaces that sometimes I trip on the sidewalk.

Online, seeing inside people’s homes is easier. All I need to do is open Pinterest or Instagram, and there are interiors laid bare for anyone to see. These images provide something different from what I can see through windows from the street, or what I once might have got from looking at decor magazines. In these online forums, interiors are not simply a glimpse at an arrangement of things; a different sense of “interiority” is evoked: People share their home-design fantasies as well as explore approaches to how they want to live in reality. Instead of a static catalog, the set pieces online shift with the focus of who’s looking, reposting, and commenting. Through hashtags and other methods of interlinking, people can show their homes while seeing how their ideas and lives fit in with others’. In fact, in this environment, showing off and fitting in become mutually reinforcing, each dependent on the other. Showing off becomes a way of fitting in rather than standing out.

With the homes I see on my street, in my physical neighborhood, we share geography but not emotional contact. Whereas with the interiors online, I’m not just on the outside looking in; I can feel as though I have a standing invitation to come inside and look as long as I want. It’s as though I’m in the midst of an imagined community, grounded not in geography but in our dreaming together of what our lives could be.

I had such communal decoration daydreams long before I ever heard of an Instagram feed. When I was little, a friend and I would build elaborate mansions in our heads. We would come up with designs that we would describe to each other, and my friend would draw it out with pencil and paper. We filled pages and pages of our made-up home with curtains, marble columns, and anything else we deemed fancy enough. These shared dreams became a medium of friendship; articulating these fantasies was a way to learn to want new things while grounding a connection that already existed. It blended the familiar with the new.

Selecting design ideas from a communal stream carries them from signifying the group to signifying the individual and back again, with one perspective never fully erasing the other

In the corners of the internet devoted to real estate and interior design, I can now iterate a series of dream homes without the pencil and paper, taking in pictures of houses from all over the world, from people with different tastes, backgrounds, and bank accounts than me. And I connect not just with friends but countless others who are doing the same thing. I can collaborate in the commentary on images; I can see how people try to solve various home-design quandaries and contribute my own ideas. Seeking design inspiration no longer need entail the isolation of window shopping. Among these communities, decorating can feel like a grassroots movement rather than a decree.

In some respects, this collective project of fantasizing how to live reflects changes in housing expectations after the financial crisis. Instead of anticipating having a house of one’s own, many people found themselves looking at renting apartments with roommates or moving into a relative’s basement. Under such circumstances it makes sense that there would be comfort in shared pictures of beautiful houses, vicarious escapes into familiar aspirations suddenly made even more remote. When I shared a bathroom with roommates, it was easy to revel in images of expansive white marble bathrooms that exuded relaxation, with large bathtubs under skylights. After I schlepped dirty clothes to the laundromat, I would click through images of perfectly organized laundry rooms, with space to sort and fold my lights and darks.

But if people find a kind of vicarious indulgence in the various images of homes and spaces online, they also may find security in the community of people posting them. Online interaction makes decorating feel more inclusive and more directly personal than when it was restricted to having guests come over (or strangers peering in). It no longer relies exclusively on mass-market magazines and their aspirational standards. And it can occur at a more theoretical, experimental level — expressing an idea through interior design no longer requires committing time and money to a particular physical arrangement of things, or special times at which such arrangements can be put on display to selected audiences. Decoration can be divorced from particular occasions and be more a matter of ongoing self-expression.

With the breadth of people sharing and resharing images online, you might expect to see a flourishing of combinations of objects and motifs, creating spaces you could never actually see in real life. With no rules to follow, someone could theoretically make an online version of their own made-up mansion, with ever wilder rooms full of fantasies. Without physical or budgetary limits, people could seemingly explore new design options with less risk, but it may be that the nature of the risk changes. The stakes are not so much making a bad investment of time and money, but expressing tastes that jeopardize one’s sense of community. In other words, if online image sharing makes for a community, it also tends to foster what communities have always fostered: conformity.

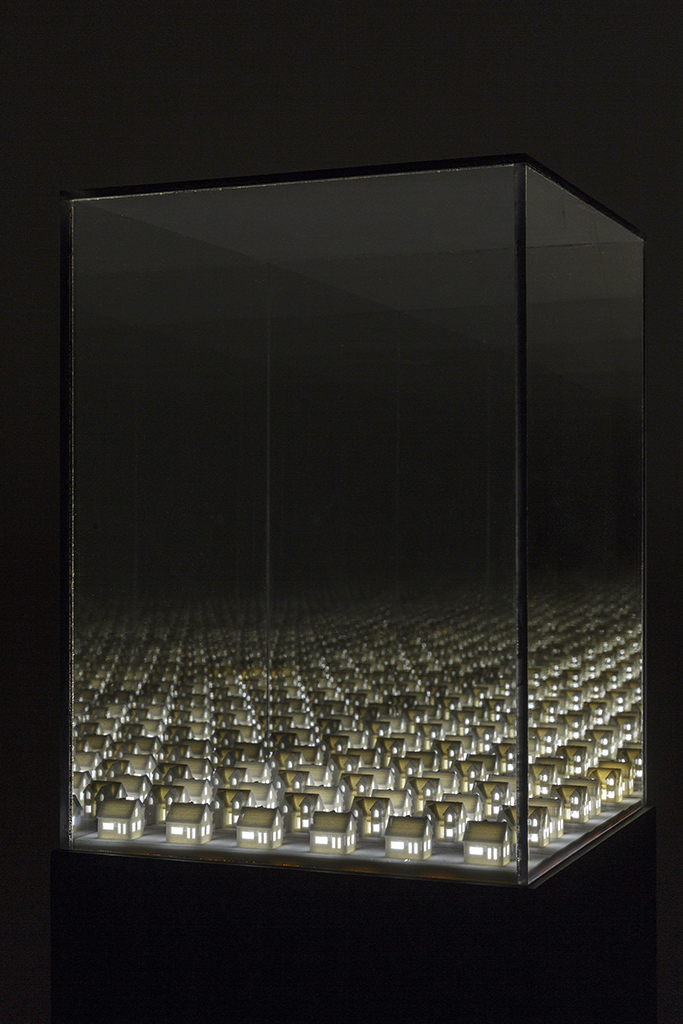

In online groups, tastes can begin to converge, focusing on the same stores, the same pieces, the same safe ideas. The sense that one’s decor is always potentially on display, capable of being posted to social media whenever, tightens the feedback loop between what is in actual homes, and what appears in the design-themed posts of our carefully chosen social media peers, which then later appears again in social media, and on and on. This ubiquity can exhaust the vitality of certain design approaches even as it makes them harder to challenge. Instead of extravagant creative visions, it’s the same couches, the same rugs, the same curtains, remixed slightly into a different combination, and then settling back into sameness — a comfortable familiarity cast in the image of furniture.

One item in particular has haunted me: A black-and-white graphic $10 pillow from IKEA has continually popped into my feed for years. Once I noticed it, I started to see it repeatedly, a plushy manifestation of the Baader-Meinhof phenomenon. I’ve seen it at home in a Brooklyn apartment, nestled into a modern leather chair, sitting on a couch on a popular TV show. The pillow looks to me like a pixelated version of an ikat pattern, an old design from Indonesia, eons older than the internet, made of intricate, repeating shapes. Because the yarn used in traditional ikat textiles is dyed before it’s hand-woven, the edges of the pattern are sometimes blurry, shapes dreamily bleeding into one another. But the IKEA pillow seems the opposite of traditional ikat: Its shapes have hard edges, it is mass-produced, and instead of dancing colors, it is black and white.

In “In Behind the Warps and Wefts: Indonesian Textiles in Context,” Brigitte Khan Majlis discusses how millennia-old textiles from the Indonesian Archipelago, like the ikat, came into Western consciousness in the early 1900s, when trading brought cultures together. “Dutch consumers became enamored with the colorful wrappers from the small island of Sumba,” she writes, “which were worn by the local aristocracy during ceremonies … such textiles were admired for their aesthetic qualities rather than for their traditional meanings and uses, which were known only to a very few Westerners.” As the pattern spread, the cultural context that went with it was lost, along with its traditional meaning. For new groups who didn’t know its history, it would mean something else, with a different sense of community born around it. For those who buy the pattern and recognize it at one other’s homes, it signifies a different sense of cultural belonging, within a globalized culture of appropriation.

The line between inspiration and appropriation is hard to draw and can be erased as quickly as a mouse click. On an individual’s Pinterest board, ikat doesn’t signify Indonesian culture so much as one’s personal inspiration and participation in a culture (Pinterest’s) that privileges such individualistic displays of taste, in the form of trends.

Interior design, like the housing market, is built on a delicate mirage: It is supposed to cast an image of the life you want to live. But the desire to be both seen and protected don’t always cohere

Just as IKEA makes style in the form of patterns like ikat available to the masses by making them cheap, sites like Pinterest democratize “inspiration” by making it systematic, breaking it down into isolated units in an endless series of reconfigurable grids. Like so many bricks, the tiny boxes on Pinterest pages stack into formidable houses built of shared dreams, and they disaggregate as easily. The context changes, meaning is erased and reconstituted, and the objects transform into something new.

In “Welcome to Airspace,” Kyle Chayka looks at how technology has pushed the same design aesthetic to different places. According to Chayka, companies like Airbnb have helped commoditize a generic look that makes users feel at home around the world. The “anesthetized aesthetic of International Airbnb Style,” he argues, comes from, in part, millions of people online “all acting and interacting more or less within the same space, learning to see and feel and want the same things.” The well-off traveling class spread their sensibilities, pollinating cities and social media feeds with images of natural wood and industrial lighting. As these tastes spread, places grow more similar. (Search #cafeculture on Instagram to see this in action.) In return, people gain an easy comfort in new places and fluency in a shorthand visual language, regardless of whether they can speak the local spoken languages. This generic style is successful for the same reason chain restaurants are: It is something familiar to hold onto no matter where you are.

At the personal level, the effectiveness of this generic design style doesn’t depend on the aesthetics of any particular pillow or light fixture. It relies instead on the ease with which such motifs circulate in images. Selecting design ideas or items from a communal stream to include in a personal vision carries them from signifying the group to signifying the individual and back again, with one perspective never fully erasing the other. Users at once express individual tastes and communal belonging.

To sustain this dual signification, a different sort of erasure is necessary: Actual people are often banished from interior design images, presumably so viewers can imagine themselves in the space instead, dreaming that they too could live inside perfection. Pictures try to look “lived in,” but in a way that no one actually lives. Books on tables can’t be too messy; blankets have to be draped just so. Styling hides imperfections, and Photoshop erases mistakes left behind by human hands. By banishing people from these pictures, the images become abstract, free from any lived context that might complicate their beauty. As context and history are lost in the online circulation of images, what’s left is varying displays of sameness.

I have developed a fear that this sameness will overwhelm me. I was broke when I was younger and moved often, and my home has its share of IKEA furniture. But I am afraid of my interiority becoming like a catalog. I am afraid of being effaced, being disappeared to wherever everyone else in interior-design images have been sent. I get furniture from garage sales and hand-me-downs from family members, and I paint what I buy to try to transform it somehow into my own. My favorite piece of art that I own is a giant painting of a ship my boyfriend and I found at a garage sale for $5. I can take comfort I won’t see it in any magazines, and it feels like the opposite of an image repinned on Pinterest. Unless (or until) I pin it there myself.

Interior design, like the housing market, is built on a delicate mirage: It is supposed to cast an image of the life you want to live. But a home is meant to shelter you from the world even while it may be meant to expose your truest you. It presumes a desire to be both seen and protected, and these don’t always cohere. I share my home online and participate in design communities partly to feel connected to others, but it also connects me to the speed of trends, the rate of their exhaustion, the process of decontextualization. At some point so many contexts will have collapsed that it may seem as though there’s nothing left for anyone to appropriate, nothing and no one new left to follow. I’m afraid that after I have opened my home to those online and off, I will still feel alone, surrounded by beautiful, generic things. It’s not the following that scares me. It’s not knowing what will happen when it stops.