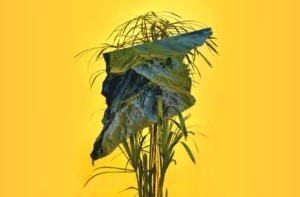

Over-articulated and hyper-literal social environments like Twitter and other text-based social media, where imprecision can have consequences and a generic logic is applied to statements with little regard for context, can also open a window for intuitive, inchoate forms of understanding: You know it when you see it. The “cursed image” meme, whose appeal lies in its inarticulability, fits this pattern. A still from a horror movie is not a cursed image, but a low-res shot of a Great Dane with red eye on someone’s dirty carpet might be. The image is a curse and not merely a scare because it raises questions, and foists an unwanted intimacy; it sticks with you.

What makes a “cursed image” disturbing is possibly the fact that it depicts something that someone else has gotten used to. But your understanding of what makes it cursed is less important than the fact that others understand it too, somehow, and also feel inscrutably uncomfortable. It feels like a psychic bond. It builds a network out of those for whom the image is abnormal and unwanted.

The same can be said for other emotional phenomena that online networks have cohered into “things”: ASMR and trypophobia, for instance, are basic tactile responses, but the fact that others share them can make them feel almost magical — a secret frequency that speaks to an ineffable connection between human beings.

Curses, in the traditional sense, build networks, uniting those who share them around something esoteric more than factual, more felt than understood: A curse unites the owners of an object, or those who look upon an image, or fail to pass on a message, or happen to upset the wrong person. “The internet’s networks produce not truth but cursedness,” Rob Horning writes this week. “Network effects serve as refractions of a curse, a remembered grievance without a clear origin point or logic but intense nonetheless.”

A superstition gains truth when enough people believe it; it might then begin to reshape reality in its image. But a curse doesn’t have to be supernatural. The story of Elliot Rodger is also a curse: It created a network out of the men who found something affirming and “true” in his actions. Gathered together, they began to recast the world with their resentments. Networks can also act like curses. Those seeking a sense of belonging and affirmation might stumble onto ideas that gain momentum and material power through participation.

This week we explore the cursed nature of networks and the networked nature of curses. Stephanie Monohan writes about legend tripping — the practice of visiting a site believed to be haunted by spirits or history, and engaging with that story in a performative way — and how it creates “incorporeal social networks.” Legend tripping, she writes, is “an open-source-esque community project” that reveals the ways in which we are always haunted by history, while affirming the communities we build around it.

Rahel Aima looks at one of the original cursed images, a painting that crossed into digital cursed dimension from its haunted, oil-on-canvas one. “Here was a painting so haunted that any representation of it, whether .png or a paper copy, had somatic effects in home viewers and home printers alike,” Aima writes, “Rather than diminishing it, each copy only seemed to amplify its power.” Whereas hauntings are site-specific — a ghost haunts a place; you move into a haunted house — a curse, like a virus, is portable, transmissible, quietly and easily acquired and difficult to shake.

We like the internet for its paranormal qualities — for the sense of telepathy we sometimes get when other people are beamed into our hands, for instance, or synchronicity when digital elements churn us at the same time across geographic distances. Paranormal metaphors — curses, hauntings — are sometimes best for describing the strange ways that online media can organize people and change them as a consequence. Cursedness is an apt metaphor for the daily anxieties of moving through online space. Being online, we “invite” ideas, images, and people into our private spaces without knowing what we bargained for; we acquire unwanted followers we can’t rid ourselves of; we are tracked by unknown entities, with no idea what they intend for us. And being online creates curses, as users cohere around “knowledge” and ideas whose accessibility belies their terrible power.

Featuring:

“Legend Tripping,” by Stephanie Monohan

“True Nonbelievers,” by Rob Horning

“The Accursed Share,” by Rahel Aima