Though we often talk about “going online,” the internet isn’t really a place. Cyberspace is a myth, as PJ Rey argued in an essay for the New Inquiry, a space “that we have set apart conceptually and subjected to ceaseless moralizing.” Accordingly, there is still a tendency to demonize being online, or worse, being “extremely online,” as aberrant, inauthentic, self-absorbed, embarrassing.

But what if we thought about the “on” of “online” not as a location — I’m on this raft of a website — but as a kind of being attuned, as in being turned on or being on trend? What if instead of an escape from being “in real life,” we think of the internet as a genre or style? “Online” can be seen as structuring an entire a way of being in the world. Akin to goth or punk or any number of cultural identities, “online” can be thought of as a way of doing things, not the place they are done.

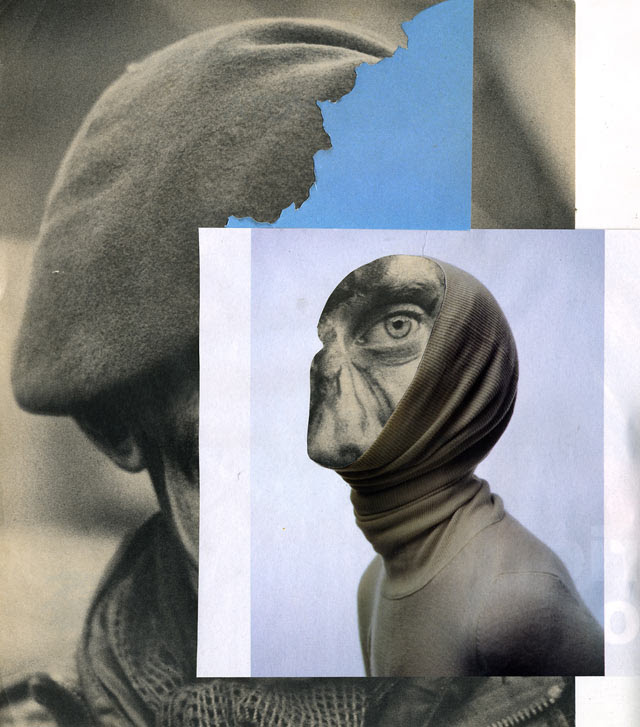

Being online may simply be a matter of having a phone, whether or not we are looking at it. To be “extremely online” would designate when the habits common to communicating with screens seep into our awareness and our identity and our behaviors regardless of the screen’s presence. Online-ness, here, isn’t a remove or a retreat from the everyday and the real but is the norm that centers us in the world and in our own heads. It is to speak in memes, to see in photos, to intuit the metrics and know what counts.

To be “extremely online” is to post and to see what has been posted as very important — and it is also to risk misunderstanding what is seen on your screens as too representative of the rest of the world, to think our niches are bigger than they are. For some, the internet, as a genre, is a low-key lower-case detached ironic nihilism. For others, it follows deep into screen-based communities founded in radical chaos or white supremacy.

This week Real Life features two essays that address becoming rather than being online. First, Rina Nkulu describes being “dressed by the internet” — “extremely online” as fashion. This is a matter of outfits worn on the body that clearly were made for and to be popular on the screen. Outfits follow from aesthetics assembled collaboratively, and personal style is subsumed by the narrative of a “-wave” or “-core” — ideas of entire lifestyles, assembled image by image, that fall away as soon as they’re established. If memes follow the logic of fashion, why couldn’t it also be the other way around?

Eric Thurm’s “How to Do Things With Memes” examines “extremely online” as a way of living out the implications of the galaxy brain meme, which in itself is part of the stock in trade of those who post. Being too online is often treated pejoratively, as indicating someone is detached and their preoccupations are inconsequential. Instead, what if being online, playing its language-games and making its jokes, stands for being alive to language and its inherent differences and contradictions? Online-ness might be understood as an openness to being continually humbled and troubled by the ever shifting contexts of conversations.

To imagine “online” as a place we can go is also to indulge the fantasy that we can simply choose to leave it behind, or refuse to go there. But we are always in the midst of the “online” way of being, whether we are looking at a screen or not.

Featuring:

“Sharper Image,” by Rina Nkulu

“How to Do Things With Memes,” by Eric Thurm

Thank you for your consideration. Visit us next week for Real Life’s next installment, ALTERNATIVE, featuring the reactionary history of 1990s alternative culture and the alternative epistemologies of Coast to Coast AM.