Food is often made to be displayed. Finished and garnished, arranged on the plate and presented on the table, the colors and textures are not just appetizing but also photogenic. It’s common for diners to choose a restaurant or what to order based on the pictures on image-centric review sites. Being eaten seems an almost unworthy fate for such well-composed displays: to be ground down by mastication and sent to an acid pit to be made into literal shit.

Cameras solve the problem of food’s ephemerality, making it outlast digestion as an image. Social media offer an audience for these images, allowing food to be more than a passing matter of sustenance or private gustatory pleasure. It can be put to work as documentation. Within minutes, hundreds of people can see your meal, with hearts and comments following in short order.

Food is central to the rhythm of everyday life, for organizing experience and taking stock of how we maintain ourselves. It’s not surprising that we would find it so photographable, and so resonant with meaning. No wonder food-prep videos go viral, and that some of the most popular reality shows focus on cooking and eating.

Critics have often condemned the impulse of some diners to photograph their food before eating it, as though the process (often a matter of a few clicks) were inevitably so elaborate and time-consuming that it destroys the sanctity and comity of the dining table. But often it’s the food of your family, capturing where you are from. The shot of the Thanksgiving turkey doesn’t undermine the holiday spirit but enhances it.

Food shared online has its own set of rituals; it taps into established food traditions rather than extinguish them. The camera is like a new utensil, affording new sorts of etiquette. It establishes a new pre-meal tradition: Documentation may function as a form of certification, a ritual that celebrates the food, offers a thought for those who aren’t present, and focuses attention on the tableau, deepening the anticipated pleasure. It can function as a complement to conventional modes of food preparation, a way of carrying it symbolically from raw to cooked.

Images of food center your own taste as well as the taste of the meal. The pictures can be a way of showing off your cooking, presentation, and hosting abilities. Your diet can demonstrate how and how much you live: your sophisticated palate and your global travels, your health and vitality, or snackwave feats of stomach. The food images can serve as emoji-like shorthand for moods — the image of perfect latté foam expressing relaxation; fast food expressing surrender.

The picture of lunch is often given as the quintessential example of social media oversharing and banality, but it’s consistent with how visual social streams generally work: They are not made of just artistically composed shots or rare, significant moments but also something more spontaneously expressive, rooted in the normal rhythms of daily experience. The photo of your mug of tea may not be exceptional aesthetically, but it serves as a small part of communicating who you are, where you are, what you are up to, how you are feeling, or who you are with. These small gestures weave the textures of life; it would be far stranger if we omitted them from social streams than return to them again and again.

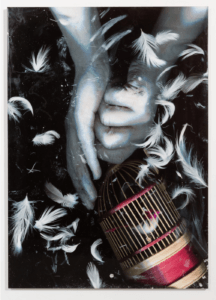

This week, Linda Besner offers a “grammar” of food online, where meals are distilled to metaphors for sex, death, and transcendence. Anya Metzer notes how pictures of food engage different senses and different kinds of pleasure beyond mere appetite. The desire sparked by an image of food can remain insatiable. And Mila Samdub writes of Village Food Factory, a YouTube channel that typifies a genre of food-prep videos that trade in fantasies of rural authenticity. These seem to show an unalienated life lived apart from capitalism, but they are carefully staged to produce and exploit that illusion.

For many, food is the simplest and most attainable kind of hedonism, a Fieri-esque basking in the accessible joys of large flavors. Though specific food images in social streams can be aspirational and snobbish, the images in their totality suggest that there are satisfactions beyond elitism, beyond competition, beyond striving, and there is no reason to heap scorn on that.

Featuring:

“Eat the Document” by Anya Metzer

Thank you for your consideration. Visit us next week for Real Life’s upcoming installment, ADULTHOOD, featuring the aesthetics of adulthood, the construction of the black family, and kid heroics.