“The souvenir,” Susan Stewart writes in On Longing, “both offers a measurement for the normal and authenticates the experience of the viewer … The souvenir distinguishes experiences. We do not need or desire souvenirs of events that are repeatable. Rather we need and desire souvenirs of events that are reportable, events whose materiality has escaped us, events that thereby exist only through the invention of narrative.” A souvenir is an object that orients us in time, positing a now and then, and a continuous self that has bridged that gap and can tell the story of how it was done.

The souvenir stands as a physical manifestation of the significance of one’s personal story, testifying, as Stewart puts it, to “the self’s capacity to generate worthiness.” Images don’t appear to provide the same singular point of contact: An iPhone picture of the beach doesn’t come only from the world of the beach. It comes also from the connected, time-and-space-flattening world of the iPhone. If the souvenir testifies to a unified self traversing time, the phone evokes a fragmented self existing everywhere and every time at once, a mass of conflicting and overlapping priorities, concerns, influences, and responsibilities. This can intensify the feeling of identity vertigo as we scale from one set of givens to a radically different one, as sets of imperatives butt up against each other in the space of a feed or an inbox.

Now that carrying a camera at all times is commonplace, taking pictures has become a primary way of engaging with experiences as they are happening. We can enjoy the idea of our future self looking back at the present moment while almost in that present moment. “The explosion of ubiquitous self-documentation possibilities, and the audience for our documents that social media promises, has positioned us to live life in the present with the constant awareness of how it will be perceived as having already happened,” Nathan Jurgenson wrote in 2011. “We come to see what we do as always a potential document, imploding the present with the past, and ultimately making us nostalgic for the here and now.” The gap between us and our future selves is short-circuited; the story to tell in that gap seems foreclosed. “Reportable” events become readily and routinely “repeatable” as periodic social media stories; images aren’t associated only with special events but become integrated as an ordinary aspect of everyday life.

But digital objects can become souvenirs, too: Old blogs or websites that have lost their expressive or active brand-making use, for instance. Email chains containing things you’d never again say to people you’d never again speak to. Picture captions and comments that situate them as documents in a social time. All of these things remind us of who we are, and what we’ve been, by orienting us relative to what we’re not. Pamela Dungao’s essay “Nostalgia for Permanence” uses Bill Brown’s “thing theory” to elucidate how these immaterial remnants can nonetheless serve as “things,” objects that have lost their immediate function and thereby take on an enhanced singularity, allowing their particular history to emerge and be foregrounded. Their souvenir-ness stems not from physical transplantation from one space to another, but from their endurance — their outliving mere usefulness.

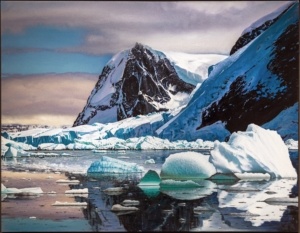

As much as souvenirs can orient us in time, other objects evoke an unfathomable scale, exposing the limits of representation and memory as guides. As Elisa Gabbert writes, very, very big objects — sources of “megalophobia” — offer a sort of cathartic terror in the face of objects too big for our minds to grasp. This sublimity may compensate for our impotence in the face of what Timothy Morton calls “hyperobjects,” something that is “massively distributed in time and space relative to humans” — global warming, nuclear fallout. We can’t begin to understand the scale of devastation we’ve already set in motion, no more than we can grasp how our daily actions bring it about. Nothing can memorialize it, no object can convey it. “How do you fight something you can’t comprehend?”

Souvenirs tend to scale experiences down to evidence of our interesting personal lives. The memories they evoke beyond our daily experience may mask what our daily choices reap. That remains a story that is hard to tell: a social life of objects that exceed any one person’s biography or ability to narrate it.

Featuring:

“Big and Slow,” by Elisa Gabbert

“Nostalgia for Permanence,” by Pamela Dungao

Thank you for your consideration. Visit us next week for Real Life’s upcoming installment, EMPATHY.