By now, the story of Miquela Sousa, aka Lil Miquela, is familiar: “She” purports to be a 19-year-old model and pop star, and has 1.5 million Instagram followers and over three million listens for her top Spotify track. She endorses clothing brands, poses for famous photographers and major publications, and has appeared in images alongside such celebrities as producer Nile Rodgers, sex educator Eileen Kelly, actress Tracee Ellis Ross, artist Chloe Wise, curator Klaus Biesenbach, and singer How to Dress Well. Just last week, she sent out a personalized email introducing her new Club 404 newsletter, a “private” vision board — but don’t worry, “the doors to the club will open VERYYYY SOON.”

An article at TechCrunch has estimated Miquela’s value at $125 million, but that isn’t her net worth — that is her value to Brud, the Los Angeles–based startup backed by Sequoia Capital that launched Sousa’s career with an Instagram profile, only revealing that it was behind the project two years later. Brud has since added two more avatars whose narratives are intertwined with Miquela’s: memester and YouTuber Blawko, depicted as Miquela’s best friend, and Bermuda, Blawko’s ex-girlfriend and Miquela’s frenemy. Miquela and Bermuda are staged as having opposing ideologies: Bermuda is pro-robot and politically conservative, praising the Trump family’s fashion sense among other things, while Miquela advocates for harmonious robot and human coexistence, and supports causes like Black Lives Matter, the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals policy, and LGBTQ rights.

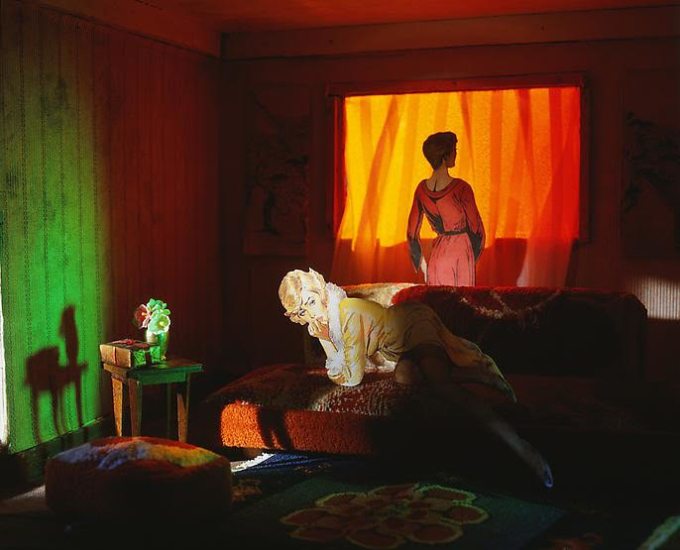

Miquela turns everything she references into a marketing posture

Brud refers to the three avatars as its “clients,” explaining in this Instagram post that it is responsible for “managing and guiding the careers of [their] artificially intelligent talent.” This extends the Svengali model that has long been a part of pop culture to its logical conclusion. Whereas pop producers like Stock Aitken Waterman in the 1980s, who produced hits for Rick Astley and Kylie Minogue among others, would help develop identities as well as songs for their acts while remaining behind the curtain, Brud can literally control every aspect of the existence of its “clients.”

One must wonder, then, to what ends Brud has invested its avatars with political trappings. In the company’s limited published statements, Brud occasionally adopts a vaguely activist tone, claiming to operate “with the belief that technology can help bring about both a more empathetic world and a more tolerant future.” This remains well within the parameters of default Silicon Valley ideology, which holds that technological innovation in and of itself is progressive. Labeling Miquela a “synthetically conscious robot” invites us to read her as Brud’s idea of how such innovation might be personified: a metaphor for the post-racial, post-gender inclusivity that the digital revolution can yield. Her appearance — slim, olive skin, pouty lips, freckle dotted face, and squarely cut bangs — is ethnically ambiguous (and categorically “attractive”), and her Instagram bio sidesteps gender identification, even though her lovey-dovey posts with indie musician Noah Gersh or her friend-zoning relationship with Blawko reproduce heteronormative expectations.

Brud has further complicated the question of its political commitments by leading Miquela on a journey of post-“woke” self-discovery. In a caption on Miquela’s Instagram, Brud had her write this:

I’m not sure I can comfortably identify as a woman of color. ‘Brown’ was a choice made by a corporation. ‘Woman’ was an option on a computer screen. my identity was a choice Brud made in order to sell me to brands, to appear ‘woke.’ I will never forgive them. I don’t know if I will ever forgive myself.

Brud thus self-awarely scrutinizes itself, anticipating potential critiques for both how it opaquely introduced Miquela into the world and its specific representational choices. These self-referential puzzles haven’t really clarified Miquela’s politics or Brud’s (they are one and the same), but it did garner the avatar and the company more attention and “influence,” the most au courant of political tactics. This semi-ironic space of plausible disavowal is consistent with alt-right strategies for attracting attention to and giving itself cover for its sexist, racist agenda.

Political meme-making has been recognized as a site for collective content generation and appreciation — memes are sourced less to individuals than to Reddit and 4chan boards or Facebook groups and meme stashes. But Miquela is individuated, and her viral content comes from the authorial voice of one venture-backed company. Rather than having, for better or worse, the evolving malleability that comes from groups sharing ideas, Miquela serves up prescribed politics as commoditized content. Her woke-about-wokeness and post-identity identity is foregrounded as a marketing construct, largely discrediting the radical potential that might be possible through an avataristic self, collective and otherwise.

The idea of an avataristic self — the hope that digitality could redefine the confines and connotations of the body — has long been a politically ambivalent concept. It has given grounding to ideas of fluid identity, helping originate cyber- and post-cyberfeminist movements, but the anonymity it affords has also empowered malicious agents and enabled hate mobs, allowing platforms like Facebook and Instagram to then demonize profiles that eschew a strict correspondence with an offline person as “fake” or inherently dishonest. It reduces the transformative potential of avatars to a mask or disguise.

Miquela’s avatar identity aligns not with fluidity but with the pre-existing model of a branded self, minus the complications of being human. It has inspired other companies to develop their own digital “clients” that, unlike most of the bots and other algorithmic agents we currently co-exist with, appear to be invested with individuated subjectivity but can nonetheless be operated entirely as fully managed acts. This lack of agency drives their marketing appeal. For investors, digital influencers promise the possibility of working with a star without any of the “real” drama: Avastars can’t suddenly develop inconvenient politics that run counter to their brand. Instead, as Brud demonstrated, their politically inflected scandals can be scripted in advance as part of their process for accruing influence. Then, the very existence of publicly lauded “avastars” can in turn be used as leverage against human influencers, who see how easily they can fall from social media grace if they don’t keep in line. Avastars therefore compound familiar strategies of identity as capital and reputation management, rather than signal potential for an expressive post-body self or selves.

As a CGI character made for marketing purposes, Lil Miquela seems derived from the example of Hatsune Miku, a schoolgirl character developed in 2007 as a personification of a voice that musicians could sample with Yamaha synthesizer software. (Her voice was actually created from that of voice actor Saki Fujita.) Miku eventually ascended to full-fledged avastar status, making international tour and television appearances as a CGI figure.

Miku was not developed with an apparent political agenda (though the character did draw on a sexist tradition — since perpetuated by most digital assistants — of linking the sound of a female voice to self-abnegating servitude). Instead, the character was always explicitly meant to represent the associated software product. Brud’s product, however, is the avatar character itself — or rather the disavowal it enables. After all, Miquela and her avatar associates don’t write #ad or #sponsored in their posts like other influencers. A different logic is at play. Miquela exists entirely within the realm of ads and sponsorship; those hashtags are prerequisites rather than caveats. Given her full subsumption within a marketing-based universe, Miquela turns everything she references into a marketing posture. Her allusions to progressive politics have the doubly damaging effect of flattening complicated, nuanced issues while subordinating politics to sales. This commercialization indicates a kind of ultimate homogenization of content, an apotheosis of the progressive influencerizing of Instagram. (However, given Brud’s opacity and tactical manipulation of its intent, who’s to say Miquela as influencer isn’t a guise for something else?)

For investors, digital influencers promise the stardom without any of the “real” drama. Avastars can’t suddenly develop inconvenient politics that run counter to their brand

When Instagram first launched, it generated many image tropes — shot-from-above food pics, selfies with inspirational quotes, #OOTD (outfit of the day), and so on — that became professionalized modes of content for the users who would master and come to dominate what the platform afforded: influencers. Their success in dictating the nature of discourse on the platform had trickle-down effects on users of all kinds, whether they were intent on gaining influencer status themselves or simply wanted to participate in Instagram’s visual culture. Brud has repackaged this culture and its underlying ideology — everything is advertising — as a product in itself.

In Gentrification of the Mind (2013), Sarah Schulman asks, “What is this process? What is this thing that homogenizes complexity, difference, dynamic dialogic action for change and replaces it with sameness? With a kind of institutionalization of culture? With a lack of demand on the powers that be? With containment?” The homogenization of content on Instagram raises similar questions. It is akin to what occurred in the 2000s as many users migrated from MySpace to Facebook — what social media researcher danah boyd described as “white flight.” boyd characterized this shift as a move away from the customization MySpace offered and toward Facebook’s standardization of aesthetic and identity (the platform required a university email address at its outset), whose apparent “conscientious restraint” conveyed typical “bourgeois fashion.”

The shift to influencer content traces a similar pattern, which Brud’s deployment of avatars consolidates and threatens to extend, closing off the alternatives beyond dichotomies that avatars might otherwise enable. For example, Katherine Angel Cross, in “The New Laboratory of Dreams: Role-Playing Games as Resistance”, describes using a World of Warcraft avatar to explore her identity as a transgender woman in a way that did not require body modification. Brud’s Miquela, by contrast, uses avataristic form, references to progressive politics, and an ethnically ambiguous appearance as veneers for a marketing approach that seeks to colonize more of the space of communication.

For all of Miquela’s talk about human-robot cooperation and the post-identity politics that seems to evoke, her conventionally attractive appearance and heteronormative behavior reinforce dualistic conceptions of male and female. Bermuda’s presence similarly reinscribes politics as a simplistic right-left binary. Such prescriptive models, whether it’s Facebook’s requisite identity boxes or the fantasized bodies that Miku and Miquela represent, inhibit any of us from moving beyond the categorical. Their avatars’ digital selves, connoting hybridity and fluidity, reinforce rigidity.

Each of us contains a spectrum of beliefs, sometimes at odds with each other even within ourselves — in other words, a spectrum of selves. Despite the apparent open-endedness of newly available channels for self-expression, that spectrum has tended to be flattened online, as “real names” policies are enforced, surveillance is the norm, and commercially oriented popularity metrics drive conventional forms of behavior.

The performative self we all play on social media is often codified into branding. Brud’s Miquela exemplifies this with a kind of visibility that militates against complexity

Brud’s avatars reinforce those tendencies, but what are the alternatives to its prescriptive models? How could they could move beyond the strictly virtual worlds and still gendered avatars that Cross depicted? One example can be found in what may seem like an unlikely source: the record producer and singer Sophie, who rose to prominence with PC Music, producer A.G. Cook’s label for exaggerated, effervescent electro pop. When PC Music somewhat mysteriously announced itself via Soundcloud in 2013, each of its acts was represented only by its online profile. The images listed with Sophie’s tracks were 3-D renders of waterslides and pool toys. Paired with vocals that were alternately high-pitched and female-sounding or androgynous and childlike, it was impossible to discern who Sophie was, if anyone at all. As Sophie’s identity became more known, music writers were quick to describe her music as a kind of sonic transvestism, a man trying on a stereotypically female sound — that is, another variation on the appropriative approach that Hatsune Miku typified.

After a few years out of public view, Sophie re-emerged in October 2017, releasing the single “It’s Okay to Cry,” a ballad that grapples with the conflicts between an internally experienced and externally projected identity. Her voice, again on an undefined spectrum between masculine and feminine, was complemented with a video that shows her body from the shoulders up — angular cheekbones, glossed lips, and peachy skin — against a constantly fluctuating cloudscape.

Given Sophie’s avatar-like origins, this song in a sense parallels Miquela’s “coming out as a robot” post. But where that corporately engineered ploy presents a “progressive” identity without any human stakes, Sophie’s “coming out” foregrounds vulnerability and frustrates pat narratives, as her rejection of “coming out” as a term suggests. In an interview with Teen Vogue, she said, “I don’t really agree with the term ‘coming out’ … I’m just going with what feels honest.”

Retrospectively, Sophie’s earlier forays into vocal manipulation could be viewed as an experimental performance of nonbinary gender. The vocals on her most recent album, Oil of Every Pearl Un-Side, are unfettered by expectations of what a female body “should” produce: They range from male to female to computer generated, sometimes within the same track. The post-production malleability of the voice has as much potential to convey the complexities of identity as modifying one’s physical appearance with makeup, clothing, hormones, or surgical interventions. Though the voice can still be fetishized (as with some other PC music acts), its manner of evoking the body does not come with the same loaded arsenal of objectification that visual representations do.

The overrepresentation in the media of whiteness and male-to-female transitions (think Caitlyn Jenner) risks reproducing gendered representations that such transitions are often at odds with — not unlike the conventionality Miquela ultimately reproduces. In Trap Door, Reina Gossett, Eric A. Stanley, and Johanna Burton noted that the supposed “‘transgender tipping point’ comes to pass at precisely the same political moment when women of color, and trans women of color in particular, are experiencing markedly increased instances of physical violence,” citing the 2015 Human Rights Campaign addressing anti-transgender violence.

Sessi Kuwabara Blanchard, in this article for Pitchfork, expands the discussion of musicians “using vocal modulation to explore gender” beyond Sophie to nonwhite musicians and female-to-male transitions. But it need not be limited to musicians: Most of us have a voice, or a synthetic one can be sampled. It can be recorded, spoken, sung, altered with digital tools, or our own perception of pitch. Therefore “the voice” itself may be an apt vehicle for bringing non-binary identity into everyday practice, online and off, rather than the overinvestment we find in body-centric visuals, and it may enable representation for a broader spectrum of people.

“Being honest,” to return to Sophie’s terminology, feels harder than ever amid a visually oriented online culture steeped in commercial and political posturing. The space for experimentation, to make (productive) mistakes, feels foreclosed; it feels increasingly difficult to participate, to perform possible selves without reinforcing normative sensibilities or being called out for hypocrisy or appropriation. The exploratory, fluid nature of Cross’s performance in WoW and Sophie’s does not make them inauthentic but in fact enables their honesty.

The performative self we all play on social media is often codified into branding, despite our best intentions. Brud’s Miquela exemplifies this with a kind of visibility that militates against complexity — what in LGBTQ studies is described as a “trap door”: Given a door, identities are trapped back into categorical boxes. Vocal modulation rather than visual representation perhaps offers one way out of this trap.

As Lee Edelman argues in No Future, queerness “never defines an identity; it can only ever disturb one.” Maybe this “disturbing,” rather than Silicon Valley’s co-option of disruption, is a useful way to frame our moving forward. A continued preoccupation with the body, whether it is in the fetishized and stereotypically normative avatars of Miku and Miquela, the gendered fantasy figures of WoW, or even body modification itself, may only perpetuate misogyny (and other power dynamics) that these disparate methods, in their distinctive ways, aim to circumvent. Couldn’t a post-body voice be the most avataristic of all?